Niki de Saint Phalle at MoMA PS1

The MoMA PS1 retrospective of sculptor Niki de Saint Phalle, sponsored by La Prairie, sheds light on the lasting impact the revolutionary artist had on the beauty industry

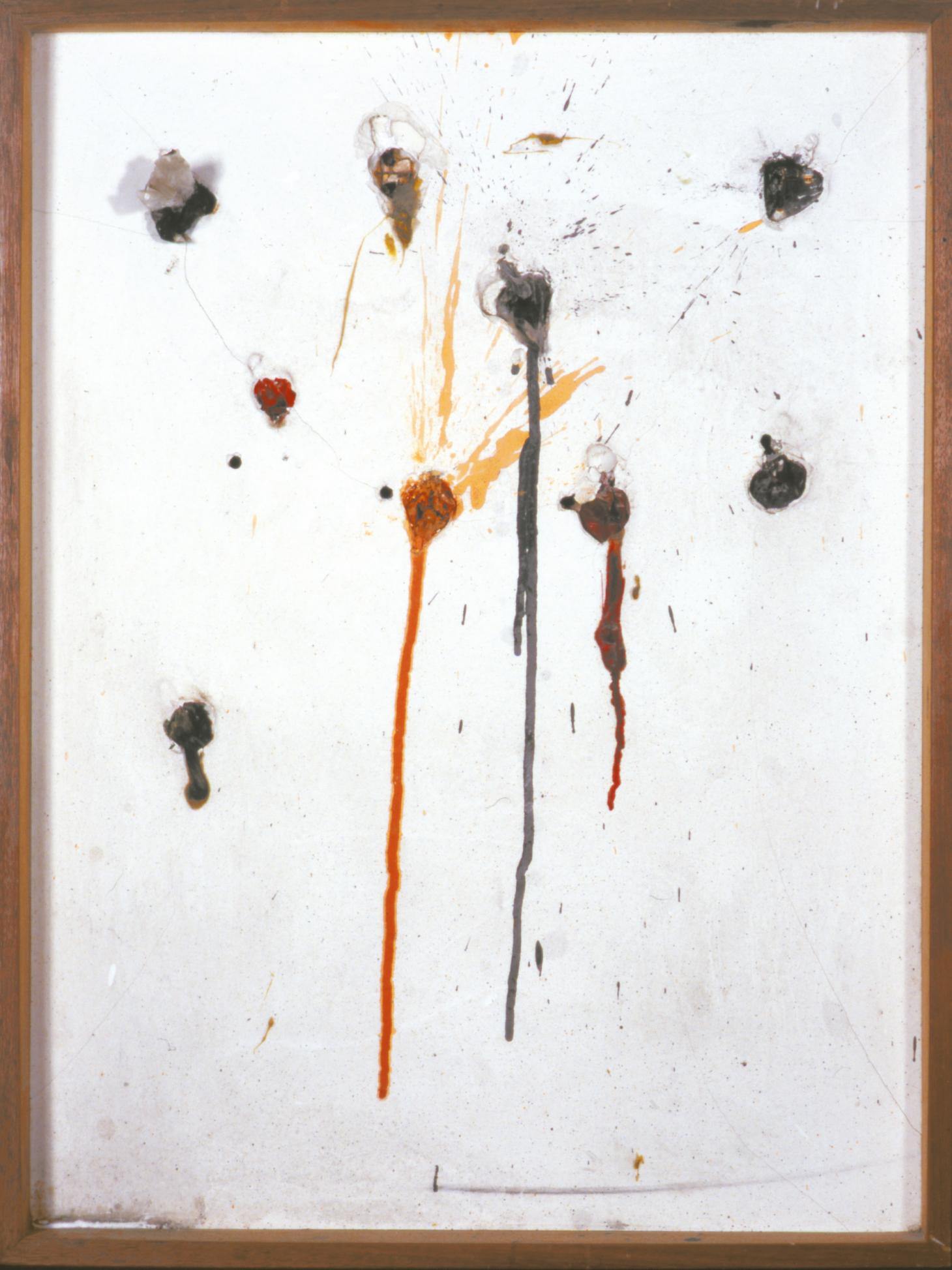

Niki de Saint Phalle enjoyed blowing things up, whether it was the plaster sculptures she filled with paint and then shot with a .22 rifle to create her Tirs series in the 1960s, or the life-size bull she once exploded with dynamite in honour of Salvador Dalí.

She certainly detonated gender norms as the only female member of the Nouveau Réalisme movement – a French artistic group that included Yves Klein and Christo, among others – and obliterated artistic conventions through her audacious and often monumental artworks, which offered a radically feminist vision of the world.

Niki de Saint Phalle, Tir neuf trous—Edition MAT, 1964. © 2021 Niki Charitable Art Foundation.

As Saint Phalle herself put it: ‘I'm not the person who can change society except by offering some kind of vision of these happy, joyous, domineering women.’

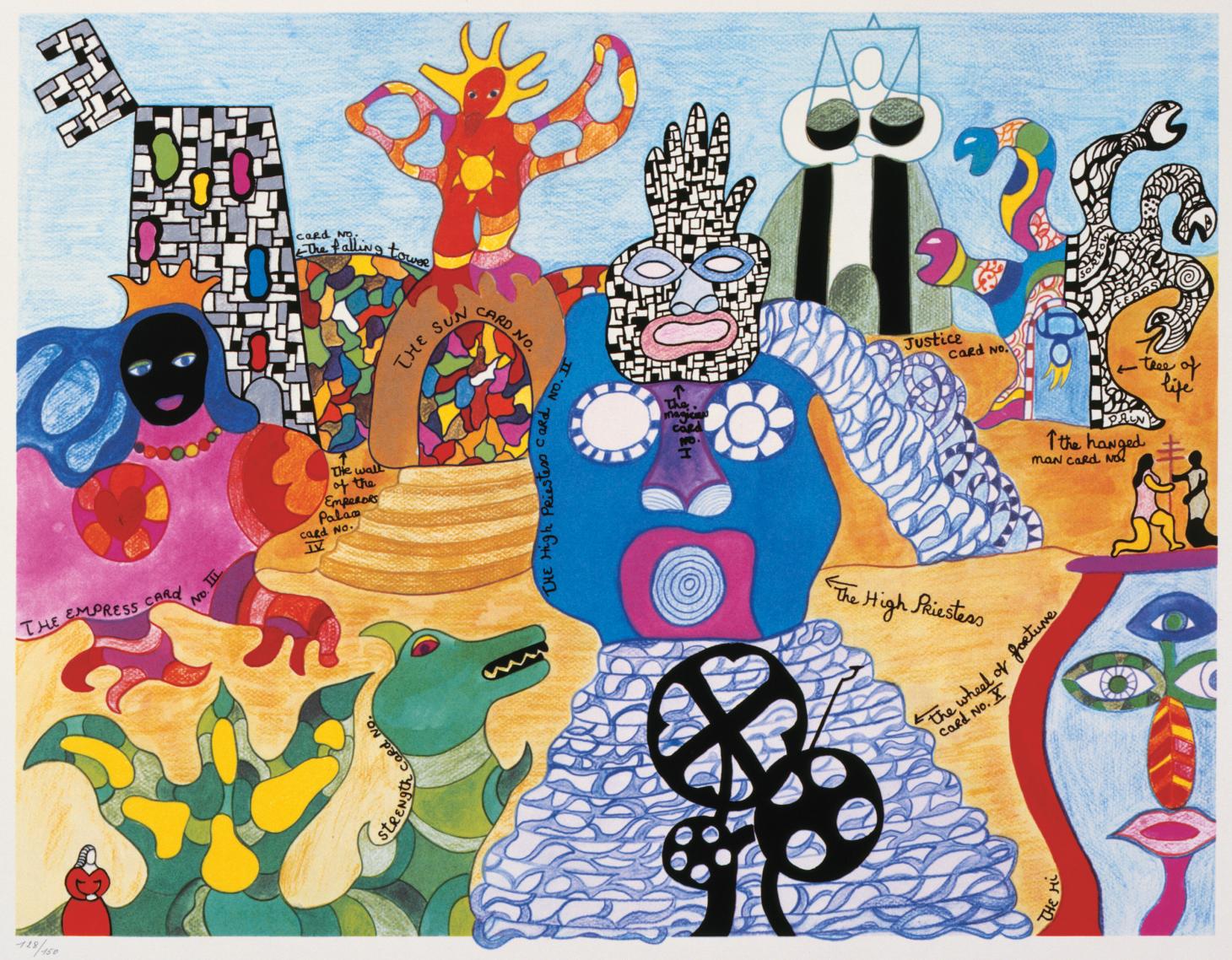

Many will recognise ‘these women’ from Saint Phalle's signature Nanas series, sculptures of extravagantly voluptuous, joyfully dancing women that recall the ancient Venus of Willendorf, but reimagined for our modern world with a psychedelic colour scheme and colossal proportions. Most notable of all, however, is Saint Phalle’s remarkable Tarot Garden, an expansive sculpture park in Tuscany populated by awe-inspiring, mammoth female figures.

Niki de Saint Phalle, Tarot Garden, 1991, lithograph. © 2021 Niki Charitable Art Foundation

Niki de Saint Phalle x La Prairie at MoMA PS1

The Niki de Saint Phalle retrospective currently on view for one more week at MoMA PS1 is a celebration of this explosive life, and work produced from the 1960s until the artist's death in 2002.

It is supported by the Swiss skincare brand La Prairie, which has a history of patronising the arts. For years, the brand has commissioned artworks for Frieze and Art Basel, funded the Mondrian Conservation Project at Switzerland's Fondation Beyeler, and also supported the mentorship of ECAL students by Wallpaper* Designer of the Year 2020, Sabine Marcelis.

Installation view of ‘Niki de Saint Phalle: Structures for Life’ on view at MoMA PS1

La Prairie's decision to support the Niki de Saint Phalle exhibition is particularly notable, both because it reveals a little known aspect of the skincare brand’s history, and also opens up the discussion on a lesser examined branch of Saint Phalle’s work.

Niki de Saint Phalle’s influence on the beauty industry

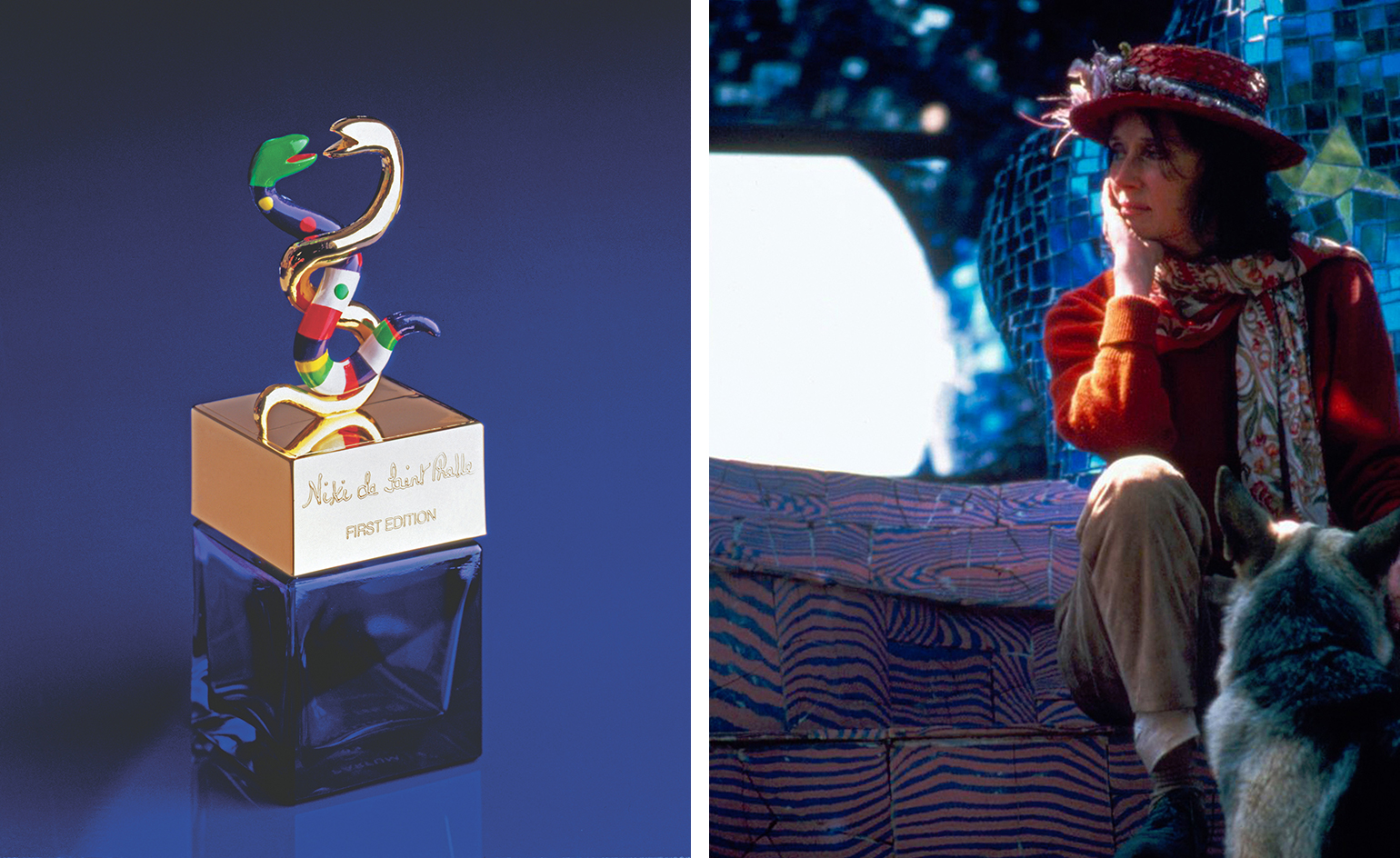

Large-scale art needs funding, as La Prairie’s own patronages over the years attest, and at the apex of her career, Saint Phalle realised she would need an alternative source of income to support her monumental, architectural projects. One of her solutions was the creation of her eponymous perfume, Niki de Saint Phalle, a peculiar chypre floral fragrance that blended notes of carnation and patchouli, with artemisia, mint, leather and sandalwood.

The blue packaging of La Prairie Skin Caviar, inspired by the shade Niki de Saint Phalle used in her fragrance bottle design

In 1980s New York, Saint Phalle was working on the fragrance in the same design studio as La Prairie's development team. It was in there that La Prairie first encountered the striking cobalt blue that Saint Phalle used for the packaging of her perfume, and which the brand eventually adopted as a signature shade of its own, most notably using it for the packaging of its Skin Caviar collection.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Speaking about the hue, Saint Phalle said, ‘I chose blue for the colour of the perfume bottle because I love blue. First of all, it’s my favourite colour. It’s the colour of the sky. It’s the colour of joy; it’s a spiritual colour. And I feel like the Greeks do, that it brings good luck.'

Installation view of perfumes at ‘Niki de Saint Phalle: Structures for Life’, on view at MoMA PS1

Although the fragrance did bring Saint Phalle some of the good fortune she needed to continue working on the Tarot Garden, she received criticism at the time for creating work with overtly commercial aims.

Yet it's fair to say that Niki de Saint Phalle perfume is just an example of the artist's pioneering vision. In recent years, a number of high-profile visual artists have experimented with perfumery, with female artists, in particular, using scent as an alternative way to examine women's place within society.

Niki de Saint Phalle with assistant Ricardo Menon, surrounded by models of monumental projects, Malibu, California, 1979.

When creating her perfume, Saint Phalle was open about the fact that she was trying to make money, but she also hit on an important, and increasingly more evident point – that perfumery has a unique ability to translate across disciplines and, ultimately, make art more accessible. A topic that many artists may continue to explore in her stead

Information

‘Niki de Saint Phalle: Structures for Life’ is at MoMA PS1 until 6 September 2021

Mary Cleary is a writer based in London and New York. Previously beauty & grooming editor at Wallpaper*, she is now a contributing editor, alongside writing for various publications on all aspects of culture.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti