On the Isle of Man, the secret history of designer Archibald Knox is revealed

The mysterious life and works of local designer Archibald Knox is celebrated in a retrospective at Manx Museum, spanning silverware, furniture, clocks and more

He may have died almost 100 years ago, but Archibald Knox is the Isle of Man’s most famous designer. His Art Nouveau silverware, his Arts and Crafts furniture, his Manx-engraved jewellery and headstones and his delicate watercolours can be found all over the island, not least at the Manx Museum in Douglas.

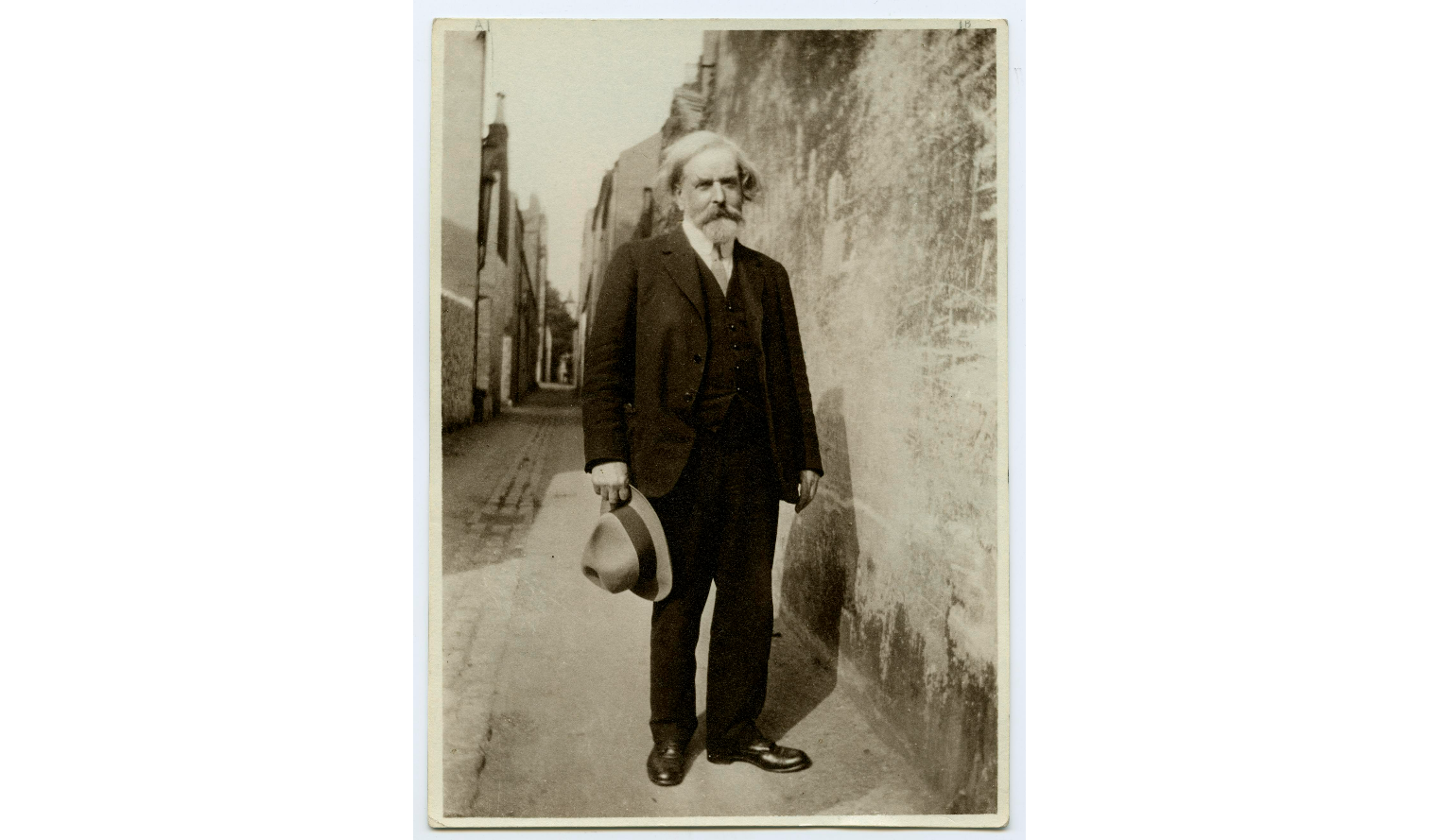

Archibald Knox in 1932, standing in a narrow lane behind 70 Athol Street, Douglas

Here, the largest ever show of Knox’s work brings together more than 200 pieces. Big hitters are the collectible silver clocks and cigarette boxes, tea caddies, ink wells and tableware, created for Silver Studio and sold in Liberty of London between 1899 and 1906. Although unsigned, they are coveted by international museums and fetch six figures at auction. (Brad Pitt is such a big collector, he allegedly named his son after the late designer.) The ‘Cymric’ and ‘Tudric’ ranges, with their Art Nouveau flourishes and Celtic engravings became best sellers, and after a spell in London, Knox worked remotely from his country cottage on the island, sending designs to the capital via the steam packet boats that crossed the Irish Sea to England every day.

When, in 1906, the Celtic Revival style fell out of fashion, the work for Liberty fell away, and Knox moved to London once more to teach. But in 1912, the Isle of Man drew him back. A prolific polymath, he became the island’s lead artist, creating furniture and letterheads, shop fronts, interiors and illustrations.

‘You cannot understand Archibald Knox and embrace his designs without understanding where they came from,’ says Katie King, curator of the exhibition. ‘The island was his muse.’ He belonged to a group of Victorian gentlemen, antiquarians and dilettantes, with fine moustaches, who were proud of their Manx heritage and set out to preserve it.

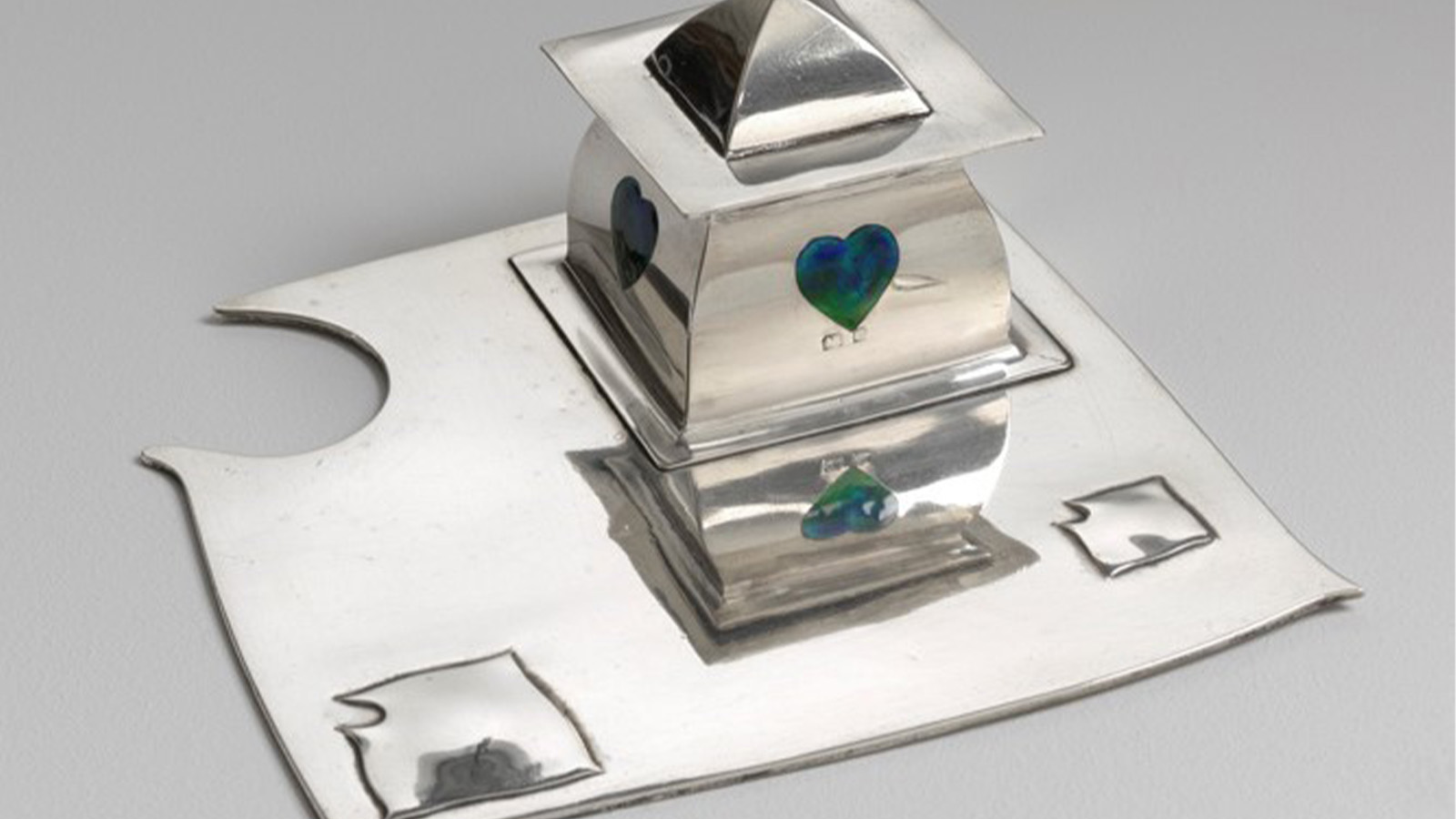

‘Cymric’ silver and enamel inkwell, model 500/31

For the pace of change in Knox’s day was rapid. When Knox left the Douglas School of Art aged 16, the island was a thriving tourist destination. Half a million tourists a year came to embrace its natural beauty. ‘It was a very exciting time, says King. ‘Hotels, dance floors and entertainment venues were built to entertain tourists, and these needed painting, so artists came flocking. There was a flourishing art scene.’

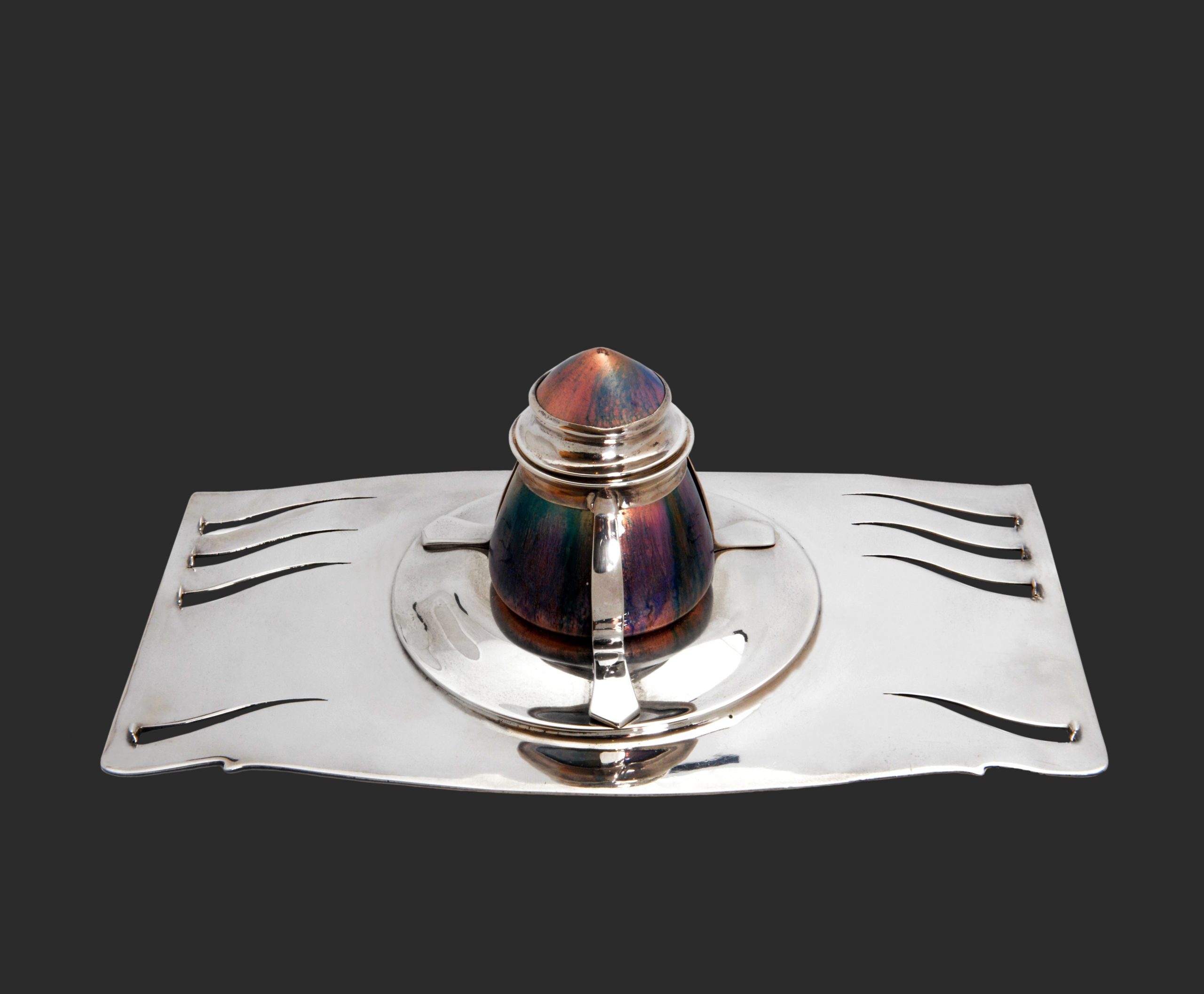

‘Tudric’ pewter inkstand with perptual calendar

Knox was in the middle of it. He translated the Isle of Man's ancient memorial stones, with their intricate interlacing, into motifs that appeared on books and buttons, letterheads, wallpapers and textiles. These particular crosses – and Knox’s interpretations of them – are uniquely Manx. The stones date back to the 11th and 12th centuries, when Norse immigrants settled on the island and developed their own styles that rebound all the way back to Scandinavia

Archibald Knox-designed writing desk or bureau, made for AJ Collister

During the First World War, Knox worked as a postal censor at Knockaloe, Britain’s largest internment camp. It was used during both wars to house enemies of the state, but the role enabled Knox to carry on painting his beloved glens, gullies and skies. It is said that Scottish designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh posted his designs to prisoners in the camp to have them made there. ‘There is no evidence that the two men were friends,’ says King. ‘But it is highly likely that their paths would have crossed, as the connections between the schools of art in Douglas and Glasgow were strong.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Liberty ‘Tudric’ pewter copper-faced clock, model 0253

Knox may have been famous on the island and admired in Arts and Crafts circles (he created Arthur Liberty's gravestone in 1917), but he never reached the giddy heights of contemporaries such as Christopher Dresser or William Morris. He was also intensely private, never married and burned and destroyed much of his work. Manx National Heritage and the Archibald Knox Forum have been collecting what’s left of his life and work since his death, in 1933, and the exhibition will form part of a wider ‘Isle of Knox’ campaign, with associated events, walks and talks taking place all year.

Successfully remaining an enigma on an island that is only 32 miles long and 14 miles wide is another of Knox’s many achievements, and the exhibition throws up many questions. But by celebrating his life and legacy, the hope is that Knox will become as synonymous with the Isle of Man as Charles Rennie Mackintosh is with Glasgow.

‘Knox: Order & Beauty’ runs until 1 March 2026, Manxnationalheritage.im

Emma O'Kelly is a freelance journalist and author based in London. Her books include Sauna: The Power of Deep Heat and she is currently working on a UK guide to wild saunas, due to be published in 2025.

-

A guide to Renzo Piano’s magic touch for balancing scale and craft in architecture

A guide to Renzo Piano’s magic touch for balancing scale and craft in architectureProlific and innovative, Renzo Piano has earned a place among the 20th century's most important architects; we delve into his life and career in this ultimate guide to his work

-

We are all fetishists, says Anastasia Fedorova in her new book, which takes a deep dive into kink

We are all fetishists, says Anastasia Fedorova in her new book, which takes a deep dive into kinkIn ‘Second Skin’, writer and curator Fedorova takes a tour through the materials, objects and power dynamics we have fetishised

-

Frank Ocean’s Homer brings its luxury jewellery and accessories to new stores in London and Los Angeles

Frank Ocean’s Homer brings its luxury jewellery and accessories to new stores in London and Los AngelesHomer is growing, with a London outpost set to appear in jewellery district Hatton Garden

-

Nature sets the pace for Alex Monroe’s first sculpture exhibition

Nature sets the pace for Alex Monroe’s first sculpture exhibitionThe British designer hops from jewellery to sculpture for his new exhibition at the Garden Museum, London. Here, he tells us why nature should be at the forefront of design

-

Wedgwood’s AI tool lets the public reimagine Jasperware for its 250th anniversary

Wedgwood’s AI tool lets the public reimagine Jasperware for its 250th anniversaryTo celebrate 250 years of Jasperware, Wedgwood debuts an AI tool that opens up the design process to the public for the first time

-

Reimagining remembrance: Urn Studios introduces artistic urns to the UK

Reimagining remembrance: Urn Studios introduces artistic urns to the UKBridging the gap between art and memory, Urn Studios offers contemporary, handcrafted funeral urns designed to be proudly displayed

-

'What Makes a Space Nigerian?' is an exhibition celebrating the key elements of West African Homes

'What Makes a Space Nigerian?' is an exhibition celebrating the key elements of West African Homes‘Our aim was to create a space that Nigerians could connect with', says Moyo Adebayo's on his latest exhibition 'What Makes a Space Nigerian?' which explores what defines a Nigerian home

-

Feldspar makes its mark on Whitehall with a festive pop-up at Corinthia Hotel

Feldspar makes its mark on Whitehall with a festive pop-up at Corinthia HotelDevon-based bone china brand Feldspar makes its first foray into shopkeeping with a pop-up at London’s Corinthia Hotel. Ali Morris speaks with the founders and peeks inside

-

One to Watch: EJM Studio’s stool is inspired by the humble church pew

One to Watch: EJM Studio’s stool is inspired by the humble church pewEJM Studio’s ‘Pew’ stool reimagines the traditional British church seating with a modern, eco-conscious twist

-

One to Watch: Family Project’s ‘furniture friends’ are elegant and humorous with lasting emotional value

One to Watch: Family Project’s ‘furniture friends’ are elegant and humorous with lasting emotional valueFamily Project, founded by Francesco Paini, is a London-based design practice drawn to human connection, creating portraiture through furniture and injecting artful expressions into interior spaces

-

‘There are hidden things out there, we just need to look’: Studiomama's stone animals have quirky charm

‘There are hidden things out there, we just need to look’: Studiomama's stone animals have quirky charmStudiomama founder's Nina Tolstrup and Jack Mama sieve the sands of Kent hunting down playful animal shaped stones for their latest collection