New exhibition, ‘Architecture for Dogs' celebrates the human-canine bond

As a showcase of designs for dogs opens in Milan, we find out why inviting our four-legged friends into exhibitions benefits everybody.

There’s no question that we are living in an era where dogs are deified – treated less as pets and more as family members. If proof were needed, look no further than the recently opened ‘Architecture for Dogs’ exhibition at Milan’s ADI Design Museum, running until 16 February 2025. First presented at Design Miami in 2012 and following a successful European showcase in London in 2020, this latest edition features canine architecture by design luminaries such as Shigeru Ban, Toyo Ito, Konstantin Grcic, and Kengo Kuma, underscoring the growing cultural fascination with our four-legged companions.

Designed with specific breeds in mind and displayed on a series of curated islands, the pieces range from the practical to the fantastical. Shigeru Ban, for instance, crafted an undulating maze and bed for a Papillon (or Continental Toy Spaniel) using ubiquitous cardboard tubes, while Reiser + Umemoto created a cloud-like orange coat tailored for a Chihuahua. Even Giorgio Armani makes an appearance, with a dog-focused capsule collection designed in collaboration with Poldo Dog Couture.

The exhibition layout, curated by Kenya Hara and the Hara Design Institute, is designed as a fluid arrangement of display islands

Curated by Kenya Hara – CEO of Nippon Design Center and artistic director of Muji – the showcase challenges conventional perceptions of pet architecture. ‘Dogs are an integral part of many households, but their needs are often met with functional, mass-produced solutions that lack consideration for individuality and emotional connection,’ explains museum director Andrea Cancellato. ‘This project invites world-class architects to reimagine this bond, creating pieces that are as much about enhancing the dog’s environment as they are about celebrating the human-canine relationship.’

NYC firm Reiser + Umemoto designed 'The Cloud' as a 'second skin' for a chihuahua, creating a 'climatic buffer' to shield the dog from cold, and providing protection for the general weakness of the breed’s bones

To mark the show’s Italian debut, two new contributions by Giulio Iacchetti and Piero Lissoni have been added to the line-up. Working with sustainable design brand Riva 1920, Iacchetti designed a round, plywood-panelled structure for an Italian Greyhound that recalls a Roman camp tent.

‘I designed the kennel as a small, self-contained piece of architecture, simply scaled down,’ Iacchetti told Wallpaper*. ‘A key aspect was the ability to construct it starting from flat elements. The result is an elegant pavilion that harmonises beautifully with the sinuous and enchanting lines of the Italian Greyhound.’

Lissoni’s cave-like plywood and aluminium kennel for a yorkiepoo takes inspiration from an airport hangar

Meanwhile, Lissoni’s plywood and aluminium kennel for a Yorkiepoo takes inspiration from an airport hangar. ‘The hangar is the primeval cave,’ Lissoni explains. ‘It’s the form we used as a home when we were animals, when we were evolving apes. I reimagined the idea of the cave as an architectural model, thinking that animals – this time, four-legged ones – could use this hangar, my technological cave.”

What sets ‘Architecture for Dogs’ apart is its participatory nature: blueprints for all the designs can be downloaded for free from the official website, inviting people worldwide to construct and customise the designs for their pets.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

We spoke with ADI President Luciano Galimberti and museum director Andrea Cancellato to learn more about the exhibition’s deeper values and why Milan provides such a receptive context for ‘Architecture for Dogs’.

Konstantin Grcic's bed for a toy poodle draws inspiration from claims by poodle owners that their pets respond positively to mirrors, exhibiting clear signs of self-awareness

Wallpaper*: ADI is one of the few museums in Milan – and across Italy – that allows dogs into its exhibition spaces. What do you think this adds to the museum experience?

Luciano Galimberti: The museum gallery, the main corridor connecting all the exhibition rooms, also functions as a public thoroughfare, linking two parts of the city. When redeveloping the industrial site that became the museum, we decided to retain this urban role, fostering cultural, social, and spatial openness.

Since its inauguration, the museum has become a vibrant hub of city life, hosting exhibitions, events, workshops, and more. It welcomes people of all ages – cyclists, wheelchair users, and dog walkers among them. Guided by Design for All principles, we embraced the inclusion of pets to reflect a clear societal trend. Italy has around 15 million pets, and in Milan, one in two residents shares their home with a companion animal.

Shigeru Ban's undulating maze and bed for a papillon (or continental toy spaniel) is made by connecting everyday cardboard tubes

These pieces aren’t purely functional; they encourage humans to rethink their role as caretakers and collaborators with another species.

Andrea Cancellato, Director of ADI Design Museum

W*: Some critics suggest that designing for dogs in this way anthropomorphises their needs. How would you respond?

Andrea Cancellato: ‘Architecture for Dogs’ isn’t just about creating ‘necessary’ items – it’s about exploring the joy and meaning behind design. These pieces aren’t purely functional; they encourage humans to rethink their role as caretakers and collaborators with another species. The designs consider dogs’ physical and psychological needs – like burrowing, perching, or observing – while engaging owners in the process of building and customising the structures. This dual approach creates a shared experience and strengthens the emotional bond between humans and dogs.

Kazuyo Sejima's dog bed for a bichon frise pays homage to the breed's distinctive, soft white fur

W*: The exhibition’s free blueprints are a unique feature. How does this change how people engage with design?

AC: By offering free blueprints, Architecture for Dogs democratises access to design, turning it into a hands-on activity rather than something meant only for viewing. This participatory approach challenges the idea that architecture is for experts or human purposes alone.

W*: Having exhibited across the globe, and now Italy, have you observed differences in how these cultures approach design for dogs?

AC: Each culture brings unique perspectives. Italy, with its deep design heritage and love for craftsmanship, has embraced the project as a celebration of artistry and cultural expression. The Italian iteration emphasises natural materials and vibrant aesthetics that resonate locally, while maintaining functionality and enjoyment for the dogs. It also adds a dialogue about how design can enhance both urban living and traditional lifestyles.

Ali Morris is a UK-based editor, writer and creative consultant specialising in design, interiors and architecture. In her 16 years as a design writer, Ali has travelled the world, crafting articles about creative projects, products, places and people for titles such as Dezeen, Wallpaper* and Kinfolk.

-

Five watch trends to look out for in 2026

Five watch trends to look out for in 2026From dial art to future-proofed 3D-printing, here are the watch trends we predict will be riding high in 2026

-

Five destinations to have on your radar this year

Five destinations to have on your radar this yearThe cultural heavyweights worth building an itinerary around as culture and creativity come together in powerful new ways

-

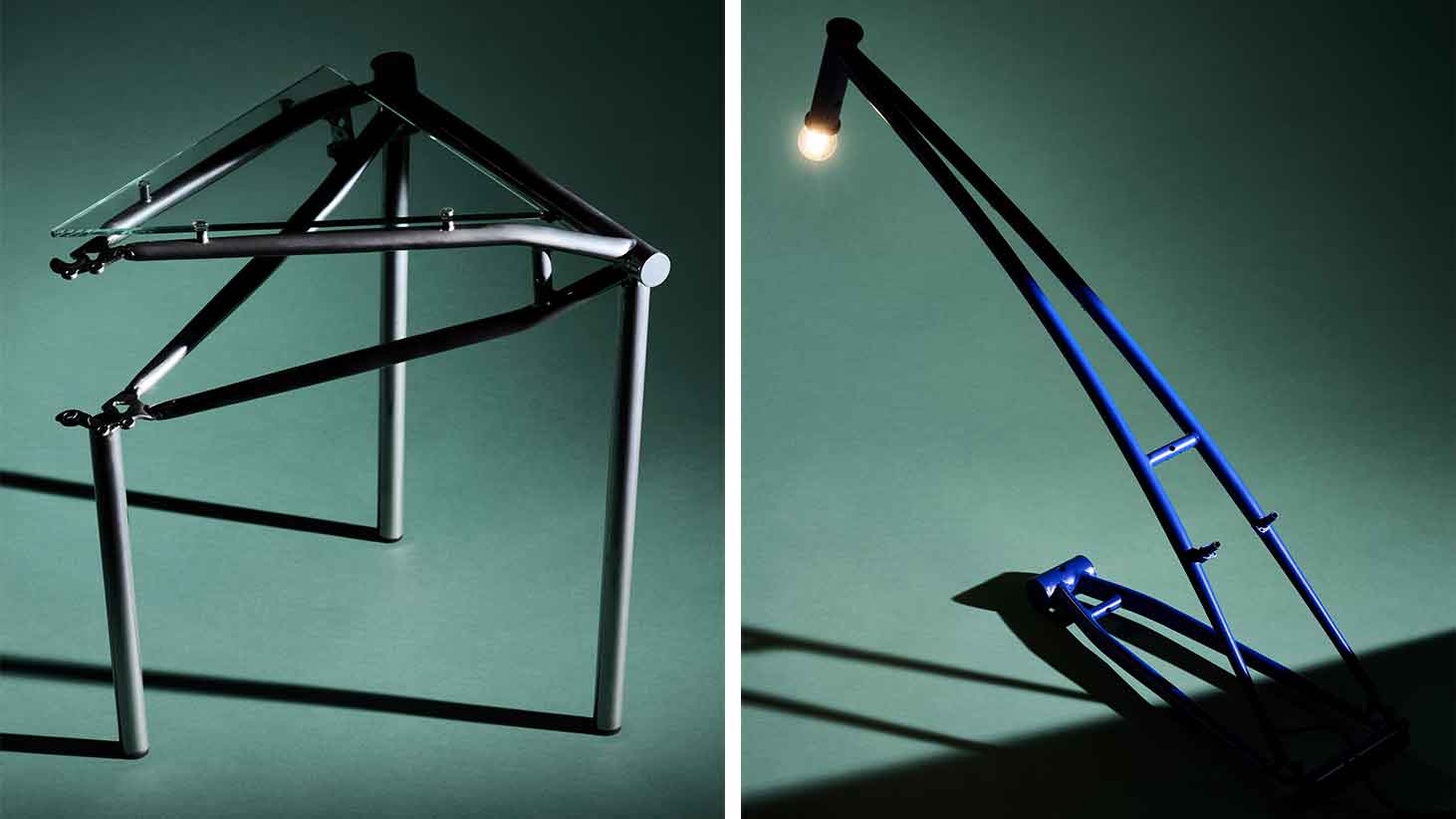

Dublin-based designer Cara Campos turns abandoned bicycles into sleekly minimal furniture pieces

Dublin-based designer Cara Campos turns abandoned bicycles into sleekly minimal furniture piecesWallpaper* Future Icons: Saudi-raised Irish/French designer Cara Campos' creative approach is rooted in reuse, construction and the lives of objects

-

Dine within a rationalist design gem at the newly opened Cucina Triennale

Dine within a rationalist design gem at the newly opened Cucina TriennaleCucina Triennale is the latest space to open at Triennale Milano, a restaurant and a café by Luca Cipelletti and Unifor, inspired by the building's 1930s design

-

20 emerging designers shine in our ‘Material Alchemists’ film

20 emerging designers shine in our ‘Material Alchemists’ filmWallpaper’s ‘Material Alchemists’ exhibition during Milan Design Week 2025 spotlighted 20 emerging designers with a passion for transforming matter – see it now in our short film

-

Tokyo design studio We+ transforms microalgae into colours

Tokyo design studio We+ transforms microalgae into coloursCould microalgae be the sustainable pigment of the future? A Japanese research project investigates

-

Delvis (Un)Limited turns a Brera shopfront into a live-in design installation

Delvis (Un)Limited turns a Brera shopfront into a live-in design installationWhat happens when collectible design becomes part of a live performance? The Theatre of Things, curated by Joseph Grima and Valentina Ciuffi, invited designers to live with their work – and let the public look in

-

Naoto Fukasawa sparks children’s imaginations with play sculptures

Naoto Fukasawa sparks children’s imaginations with play sculpturesThe Japanese designer creates an intuitive series of bold play sculptures, designed to spark children’s desire to play without thinking

-

Inside the Shakti Design Residency, taking Indian craftsmanship to Alcova 2025

Inside the Shakti Design Residency, taking Indian craftsmanship to Alcova 2025The new initiative pairs emerging talents with some of India’s most prestigious ateliers, resulting in intricately crafted designs, as seen at Alcova 2025 in Milan

-

Faye Toogood comes up roses at Milan Design Week 2025

Faye Toogood comes up roses at Milan Design Week 2025Japanese ceramics specialist Noritake’s design collection blossoms with a bold floral series by Faye Toogood

-

6:AM create a spellbinding Murano glass showcase in Milan’s abandoned public shower stalls

6:AM create a spellbinding Murano glass showcase in Milan’s abandoned public shower stallsWith its first solo exhibition, ‘Two-Fold Silence’, 6:AM unveils an enchanting Murano glass installation beneath Piscina Cozzi