Claesson Koivisto Rune on 30 years of their often Japan-inspired designs, charted in a new book

‘Claesson Koivisto Rune: In Transit’ is a ‘round-the-world journey’ into the Swedish studio's projects. Here, the founders tell Wallpaper* about their fascination with Japan, and the concept of aimai

Aimai. This Japanese word – meaning ambiguous, in-between, unclear – captures a range of concepts, from subtly indirect communication to the softly blurred boundaries of spaces. It’s one of many only-in-Japan perspectives that resonates strongly with Claesson Koivisto Rune, a Swedish design and architecture office that has balanced a deeply influential creative path in Scandinavia with inspirations from around the world for more than three decades.

And for Claesson Koivisto Rune, Japan is ‘an endless source’ of such inspiration. Its Japan journey began in the early 1990s, when co-founders – Mårten Claesson, Eero Koivisto and Ola Rune – visited separately on student scholarships, each spending a month exploring architecture across the country. Their first encounter with Japan – its aesthetics, philosophies, appreciation of beauty, craftsmanship, natural materials – left a rich creative imprint. Today, Claesson Koivisto Rune cites Japan as a signature influence in a jigsaw puzzle of inspirations, alongside other elemental ingredients such as Italian modernism and American minimalist abstract art.

Mårten Claesson, Eero Koivisto and Ola Rune at the K5 Hotel in Tokyo

The studio also has an ever-growing spectrum of Japan projects – retail flagships, furniture, exhibitions, cultural spaces – with more underway (from a hotel structure with an eye-shaped footprint to a major urban redevelopment project in the northern city of Hakodate). On the team's latest trip to Japan, they launched a series of angular faceted paper lanterns inspired by spinning tops, with longtime Japanese collaborators Time & Style, in addition to celebrating the pending launch of their new book Claesson Koivisto Rune: In Transit.

The comprehensive new monograph, published by Rizzoli on 15 November 2024, traces a journey through a curation of Claesson Koivisto Rune’s work in 26 countries, from Belgium to Botswana, exploring projects, creative encounters and design methodologies in the words of the founders. And it all starts with Japan. Here, over coffees at K5 – a Tokyo hotel designed by the studio in a former 1920s bank with flowing aimai-inspired interiors – Claesson, Koivisto and Rune talk to Wallpaper* about their ongoing Japanese journey.

Mårten Claesson, Eero Koivisto, and Ola Rune tell us why they’re big on Japan

Claesson Koivisto Rune – In Transit, available from Amazon

Wallpaper*: What role does Japan play in the new book In Transit?

Mårten Claesson: We’ve been working on the book for about three years – and on all these projects for about 30 years. It’s a round-the-world journey. Each country has a chapter – and Japan is one of the longest chapters. The countries where we’ve had the most projects are Sweden, Italy and then Japan.

W*: What’s the seed of your interest in Japan?

Eero Koivisto: All three of us have always been fascinated with Japan. This is not unusual in Scandinavia as there are many similarities between the two places. We first visited Japan in the early 1990s on scholarships when we were at university. We each came at various times for a month and travelled around looking at architecture.

W*: Had Claesson Koivisto Rune come to life at that point?

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

MC: We hadn’t yet formed the studio but we were friends. We were on the same course and became friends really quickly. A couple of years into our programme we did some school projects together and long story short, we were recognised somehow, even before graduating which led to our first commission – a big Swedish corporation asked us to make their office in Spain. It was fantastic. We were flown business class – we were students and had never heard of such a thing before.

Ola Rune: We were very well taken care of, the best clients.

MC: The manager of the big company in Sweden then said to us, how am I supposed to pay your fees? You need a company. How do you do that? Well you register one. So we registered the company when we were still at school. When we graduated in 1994, it was the worst recession in half a century with a very high unemployment rate among architects. But we had a company so thought, let’s give it a go on our own.

Left, ‘Takete’, recliner and ‘Drop Paper Lamp’, Time & Style, 2018. Right, ‘Objet d'Art Nº9’, gold plates frames and ‘Objet d'Art Nº8’, porcelain vase, Time & Style, 2018, from the book In Transit

‘In Sweden, it's very clearly form follows function. In Japan, there is a more philosophical, Zen idea about stripping away necessities’

Mårten Claesson

W*: How did that first Japan exposure impact you?

EK: It was a super strong experience.

MC: It impacted us philosophically and aesthetically.

EK: At that time, if was very unusual for Westerners to come to Japan.

OR: We had to find addresses from books and magazines, there was no Google Maps. People were very friendly and would walk us to the sites.

MC: But you couldn’t really find people speaking English in Tokyo – definitely not outside Tokyo.

EK: You couldn’t get a fork and knife outside Tokyo – impossible.

W*: What is the creative appeal of Japan?

MC: I don’t want to use the word minimalism – but there is an essentialism here, where you strip things down to the essence. There’s very little decoration. This is very similar to the Scandinavian idea of how good design should be, even if it’s for other cultural reasons.

EK: The Scandinavian style came mainly because we were very poor. Secondly, we imported kings from France – that became the Gustavian style – so we had this beautiful baroque style but without the decorations because we couldn’t afford it. We had wood floors instead of stone floors and things like that. That style fed into Swedish modernism.

MC: I think it’s also about functionalism in Sweden, which is very clearly form follows function. In Japan, there is a more philosophical, Zen idea about stripping away necessities.

EK: Also, all those gods – god of the wood, god of the windows, god of the coffee.

OR: Lots of gods. I recently went to Izumo Taisha shrine. It’s where all the gods travel across Japan to gather for a holiday in November every year.

Left, ‘Wafer’, walnut and maple wood chair, Meetee, 2015. Right, ‘Five’, Urushi lacquered chair, Meetee, 2013, from the book In Transit

W*: How did you start working in Japan?

EK: One of our first important commissions was the Sfera building in Kyoto.

OR: It came about due to our graduation project from university, which was inspired by our visits to Japan. We wanted to make an urban villa. We built it ourselves completely by hand and put it in the centre of Stockholm and called it Villa Wabi. It was a crazy project.

EK: At that time, there was a lot of talk about information stress. We wanted to build a haven for an imaginary family to live in the most disturbing and chaotic urban setting we could find. We put it in the central square of Stockholm. It’s not quite Roppongi Crossing but it was as close as we could get in central Stockholm. That’s the Japanese inspiration.

OR: If you stay in a ryokan inn, the space is used with so much reduction and simplicity. The shoji screens open and close the spaces. We were doing something similar but in a more Western way. In the whole house, every room was connected to the next spatially. There were no closed rooms. And the project was published quite widely.

W*: How did this lead you to Japan?

MC: Shigeo Mashiro – a modern cultural kingpin in Kyoto – wanted a non-Japanese to build a modern house in the middle of Gion, the historical district. He spoke to a Kyoto university professor who had read about our graduation project house in a Spanish interiors magazine and gave it to him.

EK: The house we built for him around 2001 had a cherry leaf façade of titanium. It’s like a veil, so it appears to be closed but in reality it’s not. At night, you can clearly see the structure behind it. It’s our interpretation of the traditional Japanese screen. It's a culture house with two restaurants, a shop, a gallery. This got into the Venice Biennale in both the international and Swedish sections. Because of this, we were published more widely – and then things really started.

MC: We designed a lot of furniture pieces for the house – and one of the guys making the furniture was a young Ryutaro Yoshida, founder of Time & Style.

Sfera building, culture house, Kyoto, 2003, from the book In Transit

W*: What was it like working in Japan for the first time?

OR: We learnt that you need to have patience. When you work on a project, everyone is involved and makes decisions together. So it takes a lot of time in the beginning – but then, when the project is underway, everything goes smoothly because everyone agrees.

MC: Following the construction of a project in Japan is unlike anywhere else. In other places, your efforts are focused on guarding the quality of your intentions. Here, you don’t have to do that because everyone performs at their very best. I don’t have to check that floor tiles are in line because I just know they will be. It’s wonderful in that sense to work in Japan.

W*: What key ingredients from Japan influence your designs?

EK: The philosophy, the beauty of emptiness, the way of doing things properly.

OR: How the spaces interlock.

EK: Yes, the aimai element.

W*: You have a particular affinity with the word aimai?

MC: We’d been visiting Japan for 20 years before someone taught us that word. But we had experienced it many times. That whole lost in translation concept that everyone discovers when they come for the first time is very much about aimai. There is a beauty in the vagueness – it’s not straight-lined, logical and direct like in the West. So it can be frustrating until you embrace it. Then it’s like a way of life.

OR: This hotel, K5, is an interpretation of aimai. We’re now sitting here in a café, but just over there is a wine bar and just beyond a restaurant – spatially it’s all the same, they’re not clearly divided.

EK: Our work doesn’t look totally Japanese as we’re also interested in contrasts and weird mixes. It’s like making soup, with different elements combined to form a picture.

‘I just find Japan the most civilised place on Earth’

Eero Koivisto

W*: Any other examples of key Japan projects?

EK: We designed a flagship for a company specialising in Polish ceramics in Matsumoto. It’s also aimai in a way – there is a café, a children’s book corner. So it’s a Swedish architecture office making an interior in Japan for a company selling ceramics from Poland – and we got a prize in Germany for it.

W* How does Japanese craftsmanship align with your values?

MC: Now, there is a search for appreciation of craftsmanship in the West. But in Japan it’s always been here and is more sophisticated in any imaginable craft. Wood is an obvious example. We made tables for Tokyo Craft Room at Hamacho Hotel with master craftsman Sasimonokagu Takahashi. This is a big table, with two perpendicular legs slotted into a tiny 5mm slot. To this day, I have no idea how he does it. We designed it but he solved it.

EK: He doesn’t sand surfaces – everything is concave, made using a planer. It takes about four months to make one table.

W*: Nature is another defining element in both Japan and Scandinavia – how does this influence you?

MC: It feels different. In Sweden, we love wild nature – to walk straight into a forest and hope that no one has ever walked there before. That’s our romantic idea of nature. Of course, it’s a bit the same here, but in my understanding, in Japan, the idea of Japan is more about cultivating it. If you look at the beautiful gardens of Katsuura in Kyoto, everything is meticulously trimmed with nail scissors to appear like a natural landscape. That feels like a big difference between Scandinavia and Japan.

OR: When you talk about Japan to someone who has not been here, they often think of cities. But when I travel around, often it’s only forest and mountains.

EK: Many Japanese family names come from nature. It’s the same in Finland – my name is derived from nature: it means Small Island in a Lake where Birch Trees Grow.

MC: Japan is three-quarters the size of Sweden by land – but there is a big difference in population density. We have an abundance of empty nature in Sweden which you cannot have here.

W*: Any final thoughts on Japan?

EK: I just find Japan the most civilised place on Earth. It’s not just the architecture or the design scene – it’s everything. It’s funny, Mårten has only been here since yesterday but how he speaks here is different.

MC: I can feel it affecting my behaviour in a positive way. I become more civilised just by coming here. We take inspiration from anywhere we go – we still have another 25 chapters of the book to talk about. But no other place has inspired us more than Japan.

Claesson Koivisto Rune - In Transit is $85, available to purchase via Rizzoli.com and Amazon

Danielle Demetriou is a British writer and editor who moved from London to Japan in 2007. She writes about design, architecture and culture (for newspapers, magazines and books) and lives in an old machiya townhouse in Kyoto.

Instagram - @danielleinjapan

-

Isolation to innovation: Inside Albania’s (figurative and literal) rise

Isolation to innovation: Inside Albania’s (figurative and literal) riseAlbania has undergone a remarkable transformation from global pariah to European darling, with tourists pouring in to enjoy its cheap sun. The country’s glow-up also includes a new look, as a who’s who of international architects mould it into a future-facing, ‘verticalising’ nation

By Anna Solomon

-

The Lighthouse draws on Bauhaus principles to create a new-era workspace campus

The Lighthouse draws on Bauhaus principles to create a new-era workspace campusThe Lighthouse, a Los Angeles office space by Warkentin Associates, brings together Bauhaus, brutalism and contemporary workspace design trends

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’Wallpaper* takes a tour of Extreme Cashmere’s new Amsterdam store, a space which reflects the label’s famed hospitality and unconventional approach to knitwear

By Jack Moss

-

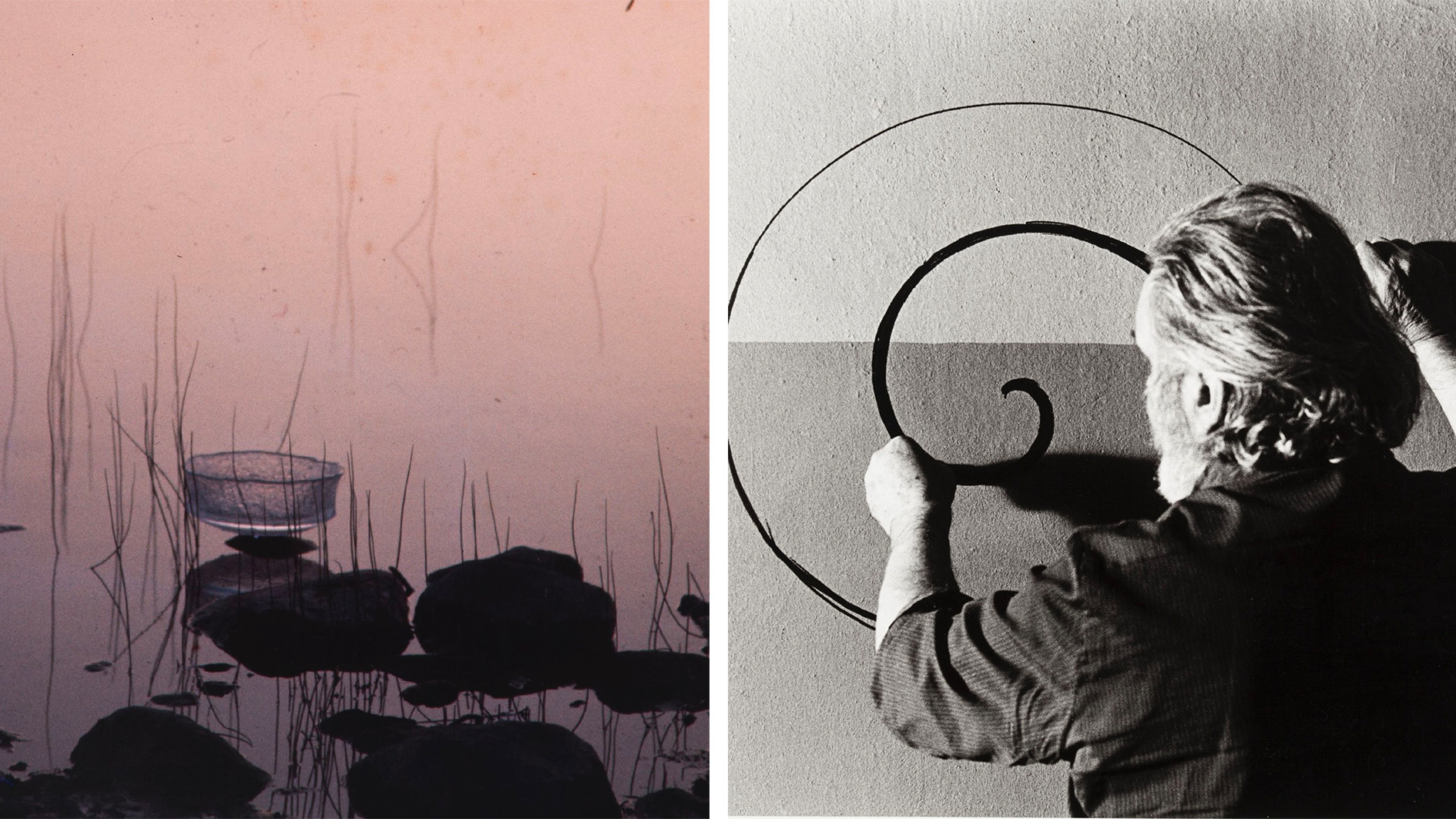

Inside the world of Tapio Wirkkala, the designer who created masterpieces in remotest Lapland

Inside the world of Tapio Wirkkala, the designer who created masterpieces in remotest LaplandThe Finnish artist set up shop in an Arctic outpost without electricity or running water; the work that he created there is now on display at a retrospective in Japan

By Anna Solomon

-

Naoto Fukasawa sparks children’s imaginations with play sculptures

Naoto Fukasawa sparks children’s imaginations with play sculpturesThe Japanese designer creates an intuitive series of bold play sculptures, designed to spark children’s desire to play without thinking

By Danielle Demetriou

-

Time, beauty, history – all are written into trees in Karimoku Research Center's debut Tokyo exhibition

Time, beauty, history – all are written into trees in Karimoku Research Center's debut Tokyo exhibitionThe layered world of forests – and their evolving relationship with humans – is excavated and reimagined in 'The Age of Wood', a Tokyo exhibition at Karimoku Research Center

By Danielle Demetriou

-

Minimal curves and skilled lines are the focal point of Kengo Kuma's Christmas trees

Minimal curves and skilled lines are the focal point of Kengo Kuma's Christmas treesKengo Kuma unveiled his two Christmas trees, each carefully designed to harmonise with their settings in two hotels he also designed: The Tokyo Edition, Toranomon and The Tokyo Edition, Ginza

By Danielle Demetriou

-

Teruhiro Yanagihara's new textile for Kvadrat boasts a rhythmic design reimagining Japanese handsewing techniques

Teruhiro Yanagihara's new textile for Kvadrat boasts a rhythmic design reimagining Japanese handsewing techniques‘Ame’ designed by Teruhiro Yanagihara for Danish brand Kvadrat is its first ‘textile-to-textile’ product, made entirely of polyester recycled from fabric waste. The Japanese designer tells us more

By Danielle Demetriou

-

Craft x Tech elevates Japanese craftsmanship with progressive technology

Craft x Tech elevates Japanese craftsmanship with progressive technologyThe inaugural edition of Craft x Tech was presented in Tokyo this week, before making its first international stop at Design Miami Basel (11-16 June 2024)

By Danielle Demetriou

-

Ikea meets Japan in this new pattern-filled collection

Ikea meets Japan in this new pattern-filled collectionNew Ikea Sötrönn collection by Japanese artist Hiroko Takahashi brings Japan and Scandinavia together in a pattern-filled, joyful range for the home

By Rosa Bertoli

-

Junya Ishigami designs at Maniera Gallery are as ethereal as his architecture

Junya Ishigami designs at Maniera Gallery are as ethereal as his architectureJunya Ishigami presents new furniture at Maniera Gallery in Belgium (until 31 August 2024), following the series' launch during Milan Design Week

By Ellie Stathaki