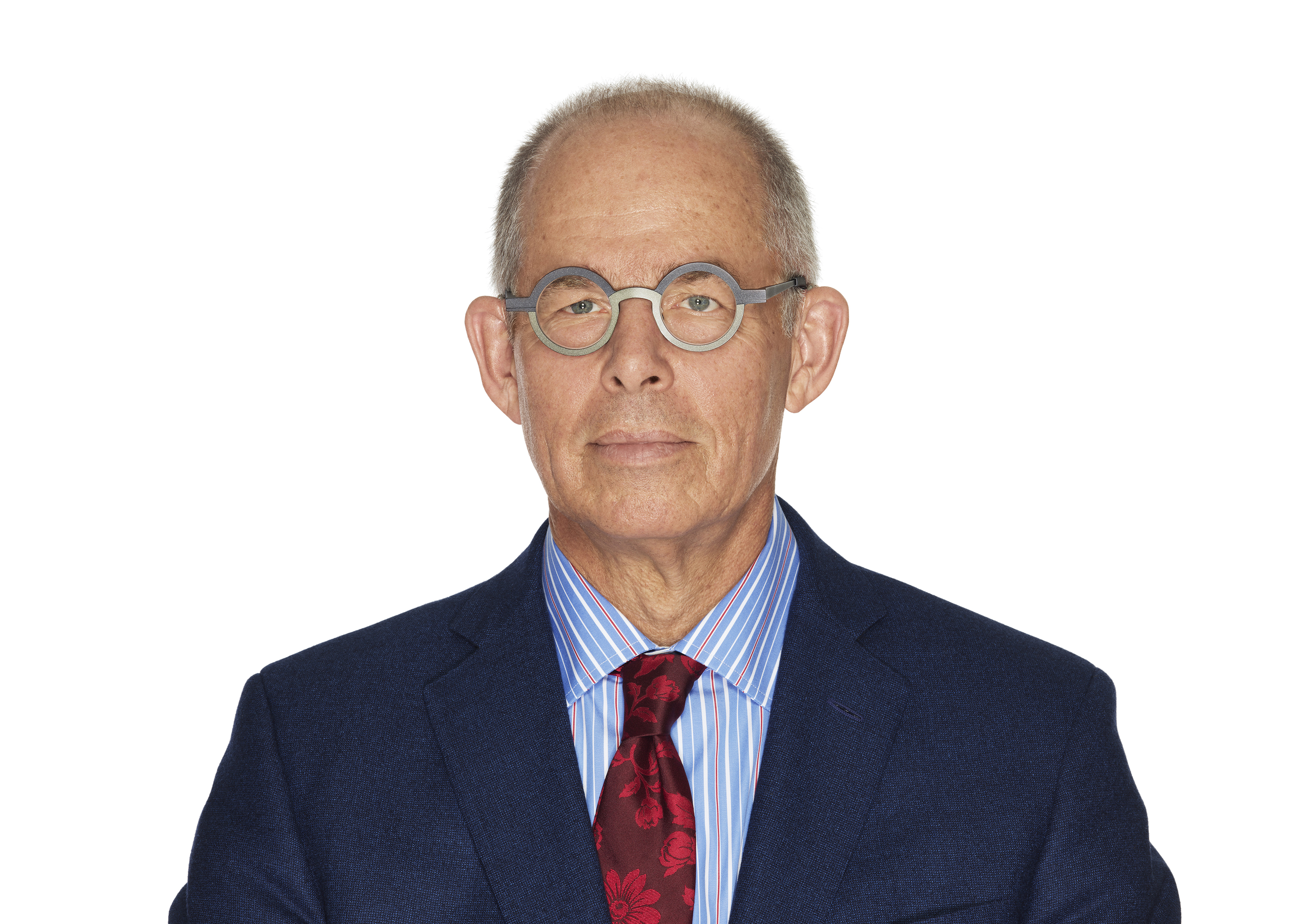

‘The people who succeed are the ones who are curious’: graphic designer and Honorary RDI Michael Bierut

New York-based graphic designer Michael Bierut – Honorary Royal Designer for Industry, Pentagram partner, and the man behind the Mastercard logo – reflects on four decades in design

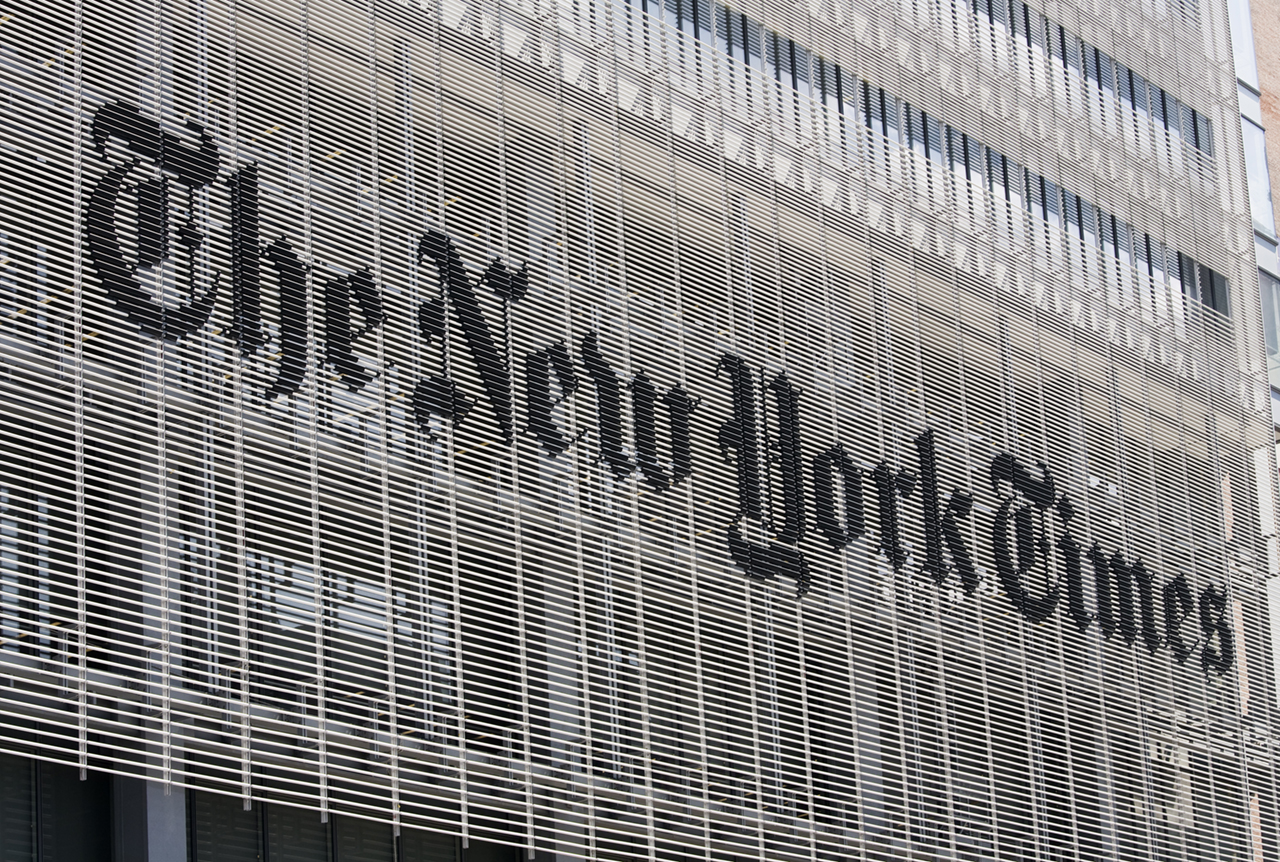

Even if you haven’t heard of graphic designer Michael Bierut, his work is likely imprinted on your subconscious. His simplified brand mark for Mastercard – two overlapping circles with no type – graces over 2.3 billion credit cards worldwide. He was the creative force behind the iconic 'H' logo for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign, authored the brand identity for Saks Fifth Avenue, and designed the massive signage on the façade of The New York Times building in Midtown Manhattan.

Born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1957 and raised in Parma, Bierut went on to study graphic design at the University of Cincinnati. After his graduation in the summer of 1980, he arrived in New York, having landed a job with legendary designer Massimo Vignelli, renowned for his 1972 New York City subway map. Since 1990, Bierut has been a partner at the renowned design firm Pentagram. Recently, after 34 years, he transitioned from leading his 12-person studio to an advisory role, collaborating with the firm's partners on diverse projects.

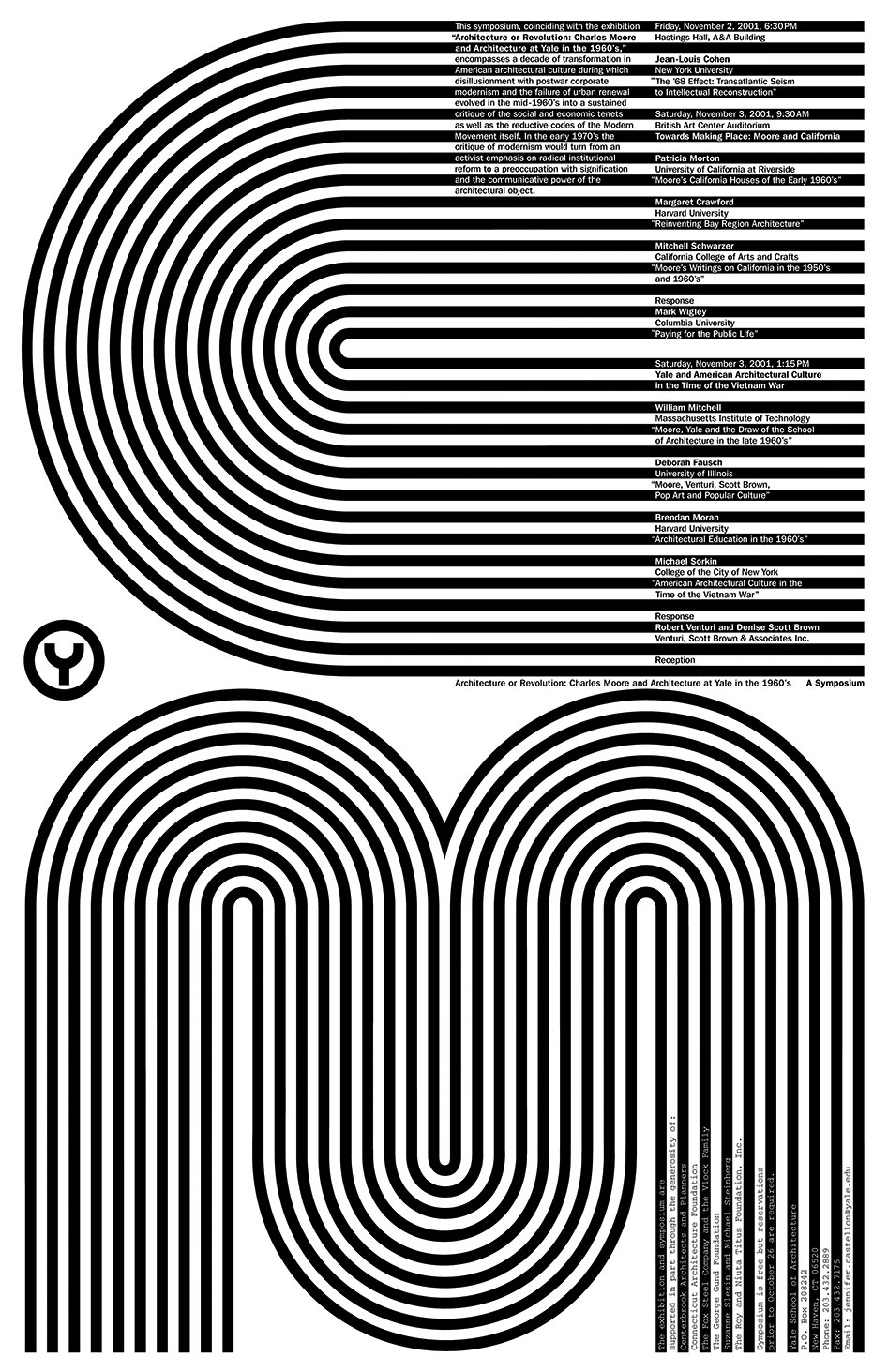

Poster by Michael Bierut for the Yale School of Architecture, 2001

Known for his ability to distil complex ideas into accessible and memorable visual forms, Bierut's deep appreciation for typography is evident throughout his projects (which Wallpaper* explored on the occasion of a 2015 Michael Bierut retrospective), where he employs type not just as a functional element but as a key narrative tool. Beyond his design work, he is an influential writer, educator, and speaker, holding the role of Senior Critic in Graphic Design at the Yale School of Art.

Wallpaper* had the pleasure of catching up with Bierut following his trip to London late last year, where he was named an honorary Royal Designer for Industry. A sharp and engaging interviewee, Bierut shares insights on the evolving design landscape, where he finds satisfaction today, and the enduring importance of curiosity and collaboration.

Hilary Clinton supporters hold up signs brandishing Michael Bierut's logo for her 2016 presidential campaign

Wallpaper*: Your role at Pentagram has recently changed, can you explain how and why?

Michael Bierut: Pentagram has this interesting structure where each partner runs an autonomous design studio within the firm. I did that for 34 years, running a little 12-person design studio. Each partner also has sole responsibility for finding clients and managing projects.

About a year ago, I wanted to extract myself from both of those things. I discovered I was taking more pleasure in coaching and guiding the designers working for me than in doing the work myself. Pentagram was founded by people who saw themselves as hands-on designers who really cared about the craft of design, which I continue to care about, but the idea that every idea has to be mine started to seem less important.

I also found that I was more excited by the work of my partners than by my own. I was surrounded by talented partners like Paula Scher, Michael Gericke, Abbott Miller, Luke Hayman, Emily Oberman, and newer designers like Matt Willey, Georgia Lupi, and Andrea Trabucco-Campos. The work they were doing became just as exciting to me as coaching the designers on my team.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘What I’ve always liked about design is the opportunity to learn something interesting about the world’

Michael Bierut

I divested myself of my team and made myself available to be of counsel to any project in the office. When an inquiry comes in, I get to do something quite delicious for me: I think about which of my partners is the perfect person to pull in on this. I either pass it to them and say, 'Let me know when the curtain goes up and I'll be in the first row clapping', or I offer my help from the wings or even on stage.

What I’ve always liked about design is the opportunity to learn something interesting about the world. Clients represent an opportunity to learn, whether it’s a law firm, an academic think tank, a historic site, or a nonprofit. It’s the substance of those things that’s really compelling to me, and that goes all the way back to my childhood when I used my art ability to get into clubs I otherwise wouldn’t have been invited into.

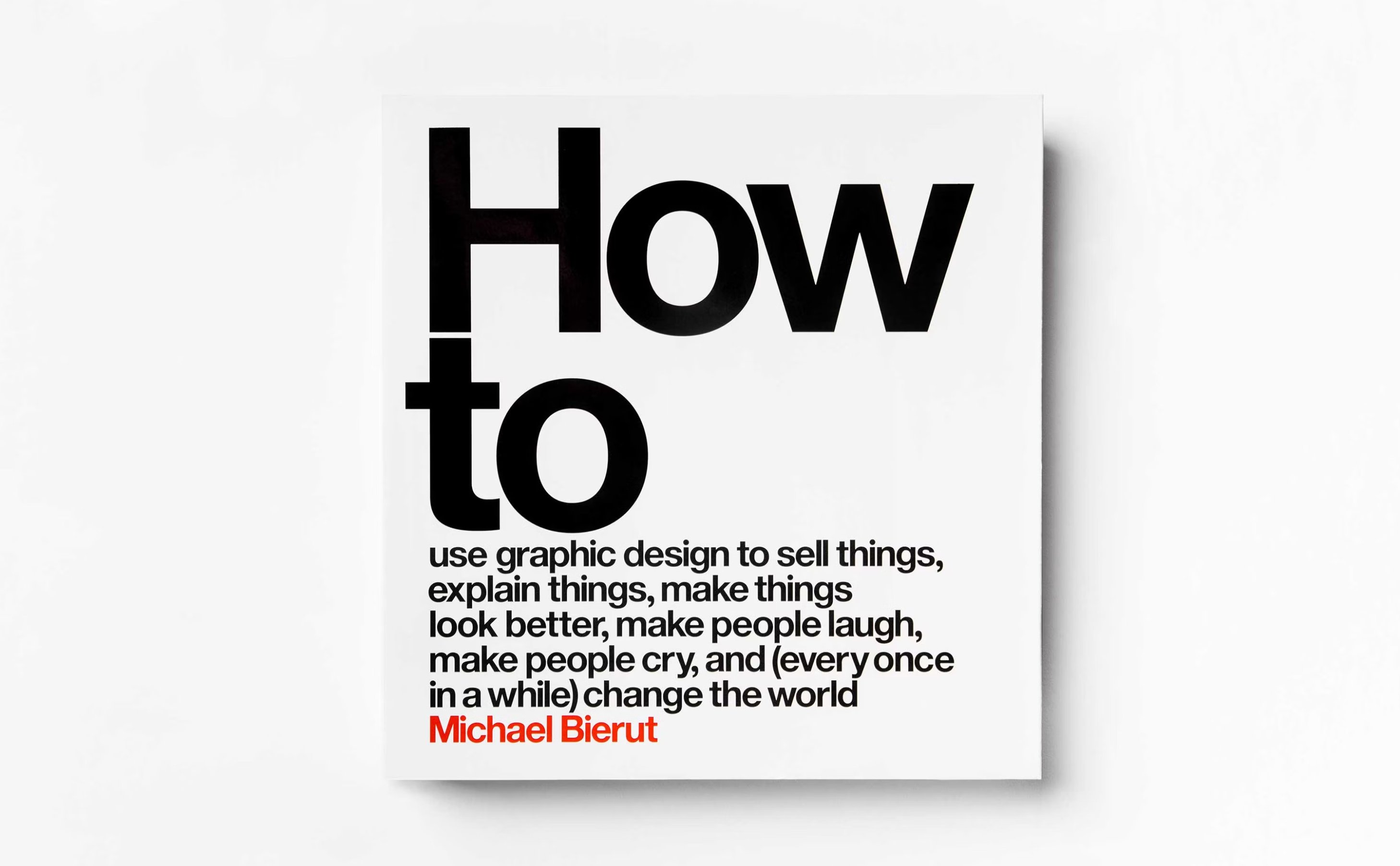

Bierut's bestselling monograph, How to, features projects for major clients, such as Mastercard and The Poetry Foundation

W*: You've previously described the sense of excitement you feel when you see your work out in the world. In this new advisory role, do you still get that buzz?

MB: I feel like I don't need that chemical hit, whatever dopamine or other kind of rush, that comes when you see your work out there. I don't crave that as much as I used to. But I still take pleasure in different ways.

I've done a number of projects with Kieran Timberlake, the architecture firm behind the US Embassy building in London. There’s a TV series now with Michael Fassbender, a spy thing [The Agency], where the CIA is headquartered in this building. It has all these glamorous establishing shots of the building. I sent James Timberlake (the firm's founding partner) a screenshot and said, ‘How does it feel to be a star?’ I got as big a kick out of that as I would seeing one of my own things there.

‘Whatever dopamine or other kind of rush, that comes when you see your work out there – I don't crave that as much as I used to’

Michael Bierut

It’s still about using design as a way to interpret the world. It doesn’t have to be my own design or something with my fingerprints on it. I still take pleasure in the fact that as designers, we’re conducting our own sort of espionage and embedding ourselves in all these different situations.

Bierut's signage for The New York Times building in Midtown Manhattan

W*: This year, you became an Honorary Royal Designer for Industry (RDI). What did that feel like and what does it mean to you?

MB: I’ve known about the RSA [the awarding body, the Royal Society for Arts, Manufactures and Commerce] and the RDI for a long time, especially being a partner at Pentagram, which has a historic London office. I’ve been close to the partners there for over three decades, and we’ve had several partners who have been RDIs. My partner Paula Scher was named an honorary one a few years ago, so I was aware of it through them.

What struck me during the induction process was how limited the membership is – only 200 people, with just a fraction being honorary positions like mine. That was one surprising aspect. The other was the extraordinary breadth of how design is conceived and interpreted. As an American, I think we tend to see design as a mid-20th-century invention tied to business – industrial design, graphic design associated with ad agencies, corporate marketing, and so on. But the RSA’s roots go back much further, to the Industrial Revolution, emphasising invention, imagination, and creativity as engines of cultural expression and economic growth.

‘I think we tend to see design as a mid-20th-century invention tied to business... but the RSA’s roots go back much further, to the Industrial Revolution, emphasising invention, imagination, and creativity as engines of cultural expression and economic growth’

Michael Bierut

The definition of design at RSA is much broader. Of all the people named RDIs this year, I probably fit the most predictable mould – graphic design and commercial art. But there are also stage designers, costume designers, and landscape architects [see Wallpaper's interviews with multidisciplinary designer Julia Lohmann and set designer Shona Heath].

During the ceremony, there was a slideshow with my work with posters, logos. These might seem like little things, but for me, the mission has always been to use my talent to insinuate myself with people who are smarter and more talented.

Beyond the prestige and honour [of the RDI awards], I was impressed by how much the RSA cultivates a sense of community. They turn that community into purposeful interactions that help move the world forward for the greater good.

Bierut's brand identity for the Wildlife Conservation Society as seen on a set of stamps

W*: When you reflect back over the past year, is there anything in the field of design that you felt particularly excited by, or, in contrast, anything that concerns you?

MB: You know, [2024] was an election year in the United States – a very wild ride. I got to know and spend a little bit of time with the team that was quickly assembled for the Kamala Harris campaign.

W*: I read that they turned that around in 22 hours, which is astonishing.

MB: Yeah, and having had some experience with political campaign graphics, seeing what they did and the fluency they had in standing that campaign up as fast as they did was really exhilarating to watch. The outcome may have been, I don't want to say preordained, but no one doing this sort of work has the illusion that tweaking a logo could turn three battleground states. It’s not about hubris. Participating in it is exciting, even though many end up on the losing side.

‘We used to spend six months crafting a logo and a thick binder of rules to dictate its usage. That used to be reassuring. But now, it’s foolhardy to think anyone will have that kind of control again’

Michael Bierut

For me, it was disappointing personally, because I don’t conceal where I stand politically. But seeing a new generation of designers engage with these issues at that level was really exciting. On a larger scale, watching this messy, scary, and constantly evolving communications ecosystem is the story of our time as a graphic designer.

A lot of my work in branding has been about giving clients a sense of permanence and control. We used to spend six months crafting a logo and a thick binder of rules to dictate its usage. That used to be reassuring. But now, it’s foolhardy to think anyone will have that kind of control again. The idea that the world seeks or is reassured by that level of control is questionable. We’re living in a time of such fluency that the only thing we can really hope to do is figure out how we'll master it going forward as the ground keeps shifting beneath our feet.

Thou Shalt Not Poop signage by Michael Bierut for the Cathedral of St John the Divine in New York City

W*: Do you feel sympathy for designers starting out in the industry today?

MB: Sympathy as in pity? Sometimes. If I were a young designer today, I think my head would explode. Back in the day, I would walk up and down bookstore aisles, digging deep into library catalogues, just seeking one book with a section on graphic design. Now, you have to confront this ceaseless deluge of visual input.

‘If I were a young designer today, I think my head would explode’

Michael Bierut

On the other hand, how great is that? It’s funny; looking back, I can’t even remember how I knew anything. When I moved to New York in 1980, I somehow knew about Massimo Vignelli; back then, it was like knowing the name of a 20th-generation Elizabethan poet or something. Today, there’s just so much information. I have sympathy for those navigating it, but I’m also excited to see how talented people respond, making it their own and breaking through the noise with original thinking.

I admire designers I’ve never met, people I know only through their Instagram feeds. I take pleasure in seeing their work pop up on my phone when I'm riding the train in the morning. The barriers are still there, of course, but the virtual world offers more routes for people to get their talent out and their voices heard.

W*: It's a bit more democratic, maybe?

MB: Or anarchic!

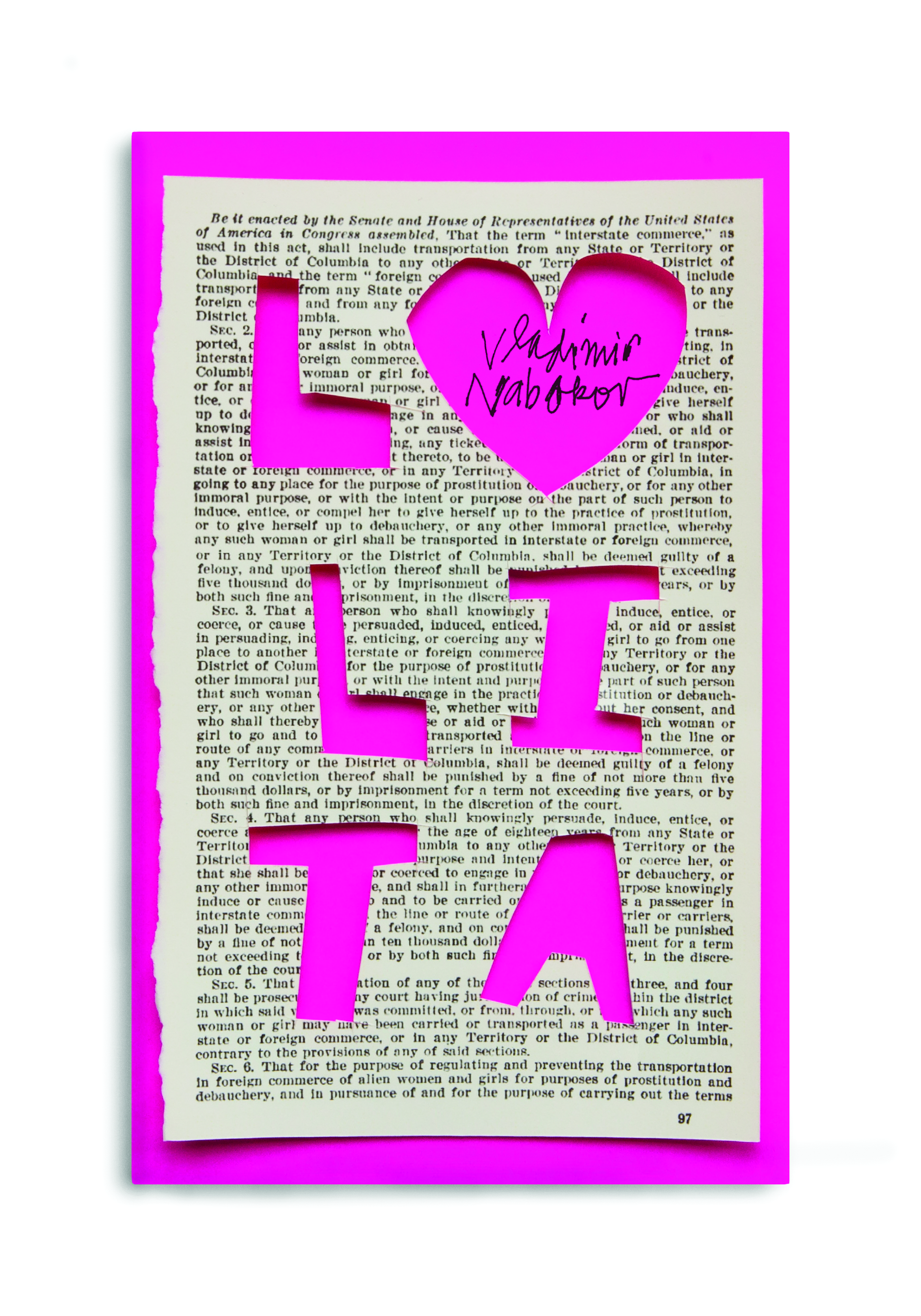

Book cover concept by Michael Bierut for the classic book Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

W*: What advice would you give to someone starting out in graphic design today?

MB: I think the people who succeed are the ones who are curious. If you're curious, you can use your talent as both an engine and a vehicle for your curiosity. I can't think of many designers who have succeeded with an incurious mind. It's not impossible, but it's rare.

Every person I've seen succeed in design, especially those I was on the stage with at the RDI [awards], had this very active, probing intelligence. They were clearly connected to the work that brought them to that point in their careers, but also expanding their thinking in all directions.

‘I can't think of many designers who have succeeded with an incurious mind. It's not impossible, but it's rare’

Michael Bierut

Curiosity is something you can have from day one – whether it’s your first day of school, your first job, or arriving in a new city. It doesn’t require experience or wisdom, which come later. But curiosity, that’s immediate.

When hiring, I looked for that curiosity. The last thing I wanted was for someone to be working on a task without understanding the bigger picture. I remember seeing puzzled expressions on new interns or team members when I explained the context of a project. They were just waiting to hear what they had to do and when it was due, so they wouldn’t let me down. But I wanted them to grasp the broader issues, even if it seemed over their heads at the time.

On my first day in New York City in 1980, I was so far over my head that I’m not sure I ever quite caught up.

Bus graphics by Michael Bierut for the New York Museum of Art and Design

W*: What are you looking forward to in 2025?

MB: You probably don't want to quote me on this, but I’ll give you the honest answer. Midway through last year, which was pretty busy for me, I got summoned for jury duty. In the US, there’s something called Grand Jury Duty, which lasts for a full month. You’re deciding whether to indict on multiple cases brought by prosecutors. It’s not trial jury duty; you’re just determining whether cases should go to trial.

I’ve put it off twice, but now it looks like I’ll have to do it in January [2025]. So here’s my fantasy: I’m going to take my unfinished copy of Robert Caro’s four-volume biography of Lyndon Johnson. I’ve read his first book, The Power Broker, about Robert Moses, which is one of my all-time favourites. But I’ve never had the nerve to tackle the Lyndon Johnson biography.

I specifically got it for jury duty, because there’s a lot of waiting around – moments of excitement followed by sheer boredom. Instead of just looking at my phone, I thought I’d bring this book and work my way through it. So my January plan is set: Jury Duty with Robert Caro.

W*: You’ll be a leading authority on Lyndon Johnson by February!

MB: And I’ll probably get a stupendous amount of privacy and isolation while serving, because people will see me as this nerdy old guy with his face stuck in a big book and just say, 'Let’s leave him alone.'

Each year the RSA puts out an open call for RDI nominations. For updates on 2025 nominations, follow @therdifaculty on Instagram. The RSA also hosts a series of open Summer Sessions – intergenerational gatherings where RDIs, emerging designers, scientists and engineers. can share, inspire and challenge.

royaldesignersforindustry.org

pentagram.com

Ali Morris is a UK-based editor, writer and creative consultant specialising in design, interiors and architecture. In her 16 years as a design writer, Ali has travelled the world, crafting articles about creative projects, products, places and people for titles such as Dezeen, Wallpaper* and Kinfolk.

-

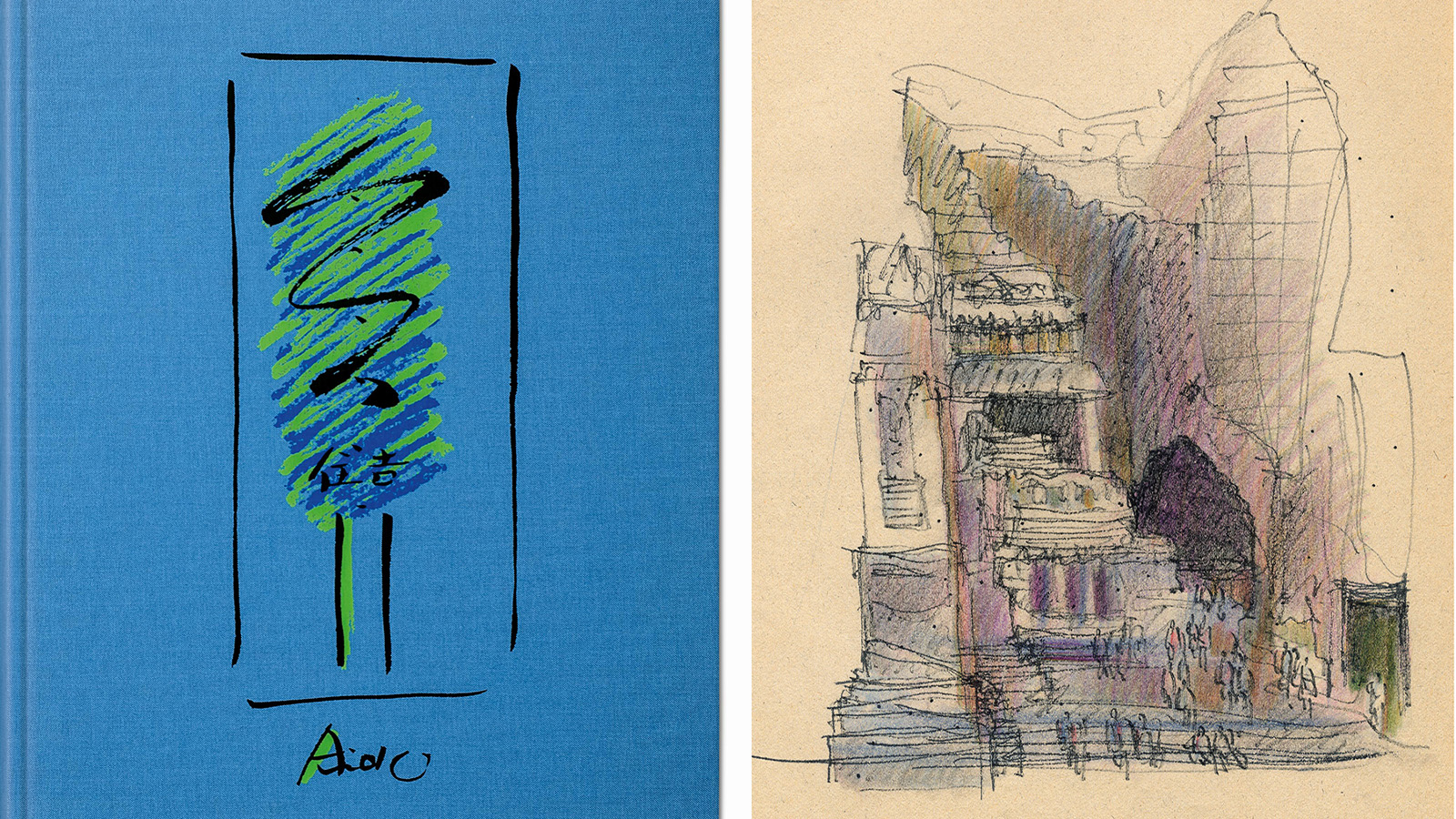

A new Tadao Ando monograph unveils the creative process guiding the architect's practice

A new Tadao Ando monograph unveils the creative process guiding the architect's practiceNew monograph ‘Tadao Ando. Sketches, Drawings, and Architecture’ by Taschen charts decades of creative work by the Japanese modernist master

-

Inside the sculptural and sensual philosophy of jewellery house Renisis

Inside the sculptural and sensual philosophy of jewellery house RenisisSardwell, founder of jewellery house Renisis, draws on sculpture, travel and theatre to create pieces that fuse sensual form with spiritual resonance

-

Feldspar's furniture is designed to make you smile

Feldspar's furniture is designed to make you smileFeldspar's furniture debut includes a dining table, side tables, a bench, a floor lamp and the possibility of a cheval mirror, all made in their workshop in Devon

-

Two new books examine the art of the logo, from corporate coherence to rock excess

Two new books examine the art of the logo, from corporate coherence to rock excessPentagram’s new book reveals 1,000 brand marks, while the art of the band logo is laid bare in Logo Rhythm

-

Californian dream: Kelly Wearstler opens a soulful shop at Harrods

Californian dream: Kelly Wearstler opens a soulful shop at Harrods