Hooked on Broadway, David Rockwell's standout stage sets and intimate design ethos

David Rockwell has created a host of standout stage sets for Broadway shows, with London’s V&A recently acquiring four for its theatre and performance collections

In David Rockwell’s Manhattan office, there is a room filled with dozens of models for the musical and theatre sets he has designed over the years. The shelves are lined with miniature worlds rendered at a half-inch scale: tiny cardboard cut-outs of the shoe factory in Kinky Boots; a remarkably realistic Streamline Moderne train carriage from the set of On the Twentieth Century; and matchbox-sized versions of the pool table that appeared in the production of The Nap. In the centre of the room stands a long table for meetings with directors and choreographers, and toward the back are the desks of the designers busily at work on new productions.

‘That room, for me, was like how you imagine Father Christmas’ workshop to be, filled with the most magical toys and gems that you’re ever going to find,’ says Simon Sladen, senior curator of modern and contemporary theatre and performance at the Victoria & Albert Museum, which has recently acquired the original set models for four David Rockwell-designed performances – the aforementioned productions, plus Hairspray. ‘When I first walked in, I was probably just a rage of jealousy that we would never be able to acquire all of those materials or have so many on display.’

David Rockwell standout stage sets

Various sets for the 2018 Broadway production of The Nap included one for the World Snooker Championship, in which a real game of snooker is played

Rockwell, who launched his cross-disciplinary architecture and design practice in 1984 (and features in 2024’s Wallpaper* USA 400, a guide to creative America), has created more than 50 sets for plays and musicals, but the role of theatre in his work runs much deeper than any individual project; it’s integral to the way he thinks about architecture.

The set for the 2013 Broadway production of Kinky Boots needed to transition seamlessly between a shoe factory in Northampton and the catwalks of Milan

He doesn’t have a signature style, but he does have a signature ethos: to Rockwell, the core principles of theatre and good design overlap and involve the thoughtful consideration of narrative, movement, scale and intimacy in order to create memorable and empathetic experiences. Architects, after all, are builders of worlds, whether it’s the set for a performance dreamed up by a playwright or a hotel, office or restaurant. ‘Architecture and theatre are both defined by the people that inhabit and animate them,’ he writes in his 2021 book Drama.

The set for the 2015 Broadway production of On the Twentieth Century consists of a 1930s-inspired train that rotates 180 degrees to reveal exterior and interior

‘We start by asking not how something is going to look, but how we want the audience to feel.’ Rockwell’s love of theatre – both real and metaphorical – predates his career as an architect. He was raised in suburban New Jersey, where his mother, a vaudeville dancer and choreographer, organised community theatre productions, and he participated in all aspects of them, from acting to playing in the orchestra and working on sets.

When he was 12, he visited New York City for the first time to see the original production of Fiddler on the Roof, after which he was hooked on Broadway. Soon after, his family moved to Guadalajara, Mexico, where he encountered a vibrant public life, particularly its restaurant scene

2015 Broadway production of On the Twentieth Century

It’s no wonder, then, that his work has involved building spaces that foster conviviality. ‘There were things that connected those experiences, and one was a hunger and a love for live experience,’ says Rockwell. ‘And I felt very compelled by that.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

A continual feedback loop exists between his work for theatre and the rest of his creative practice. He thinks like a director when it comes to his hotels and restaurants, which include a 30-year collaboration with chef Nobu Matsuhisa and establishments for culinary heavyweights including Jean-Georges Vongerichten, José Andrés and Daní Garcia. Meanwhile, he thinks like an architect when it comes to sets, which is rare in the world of theatre.

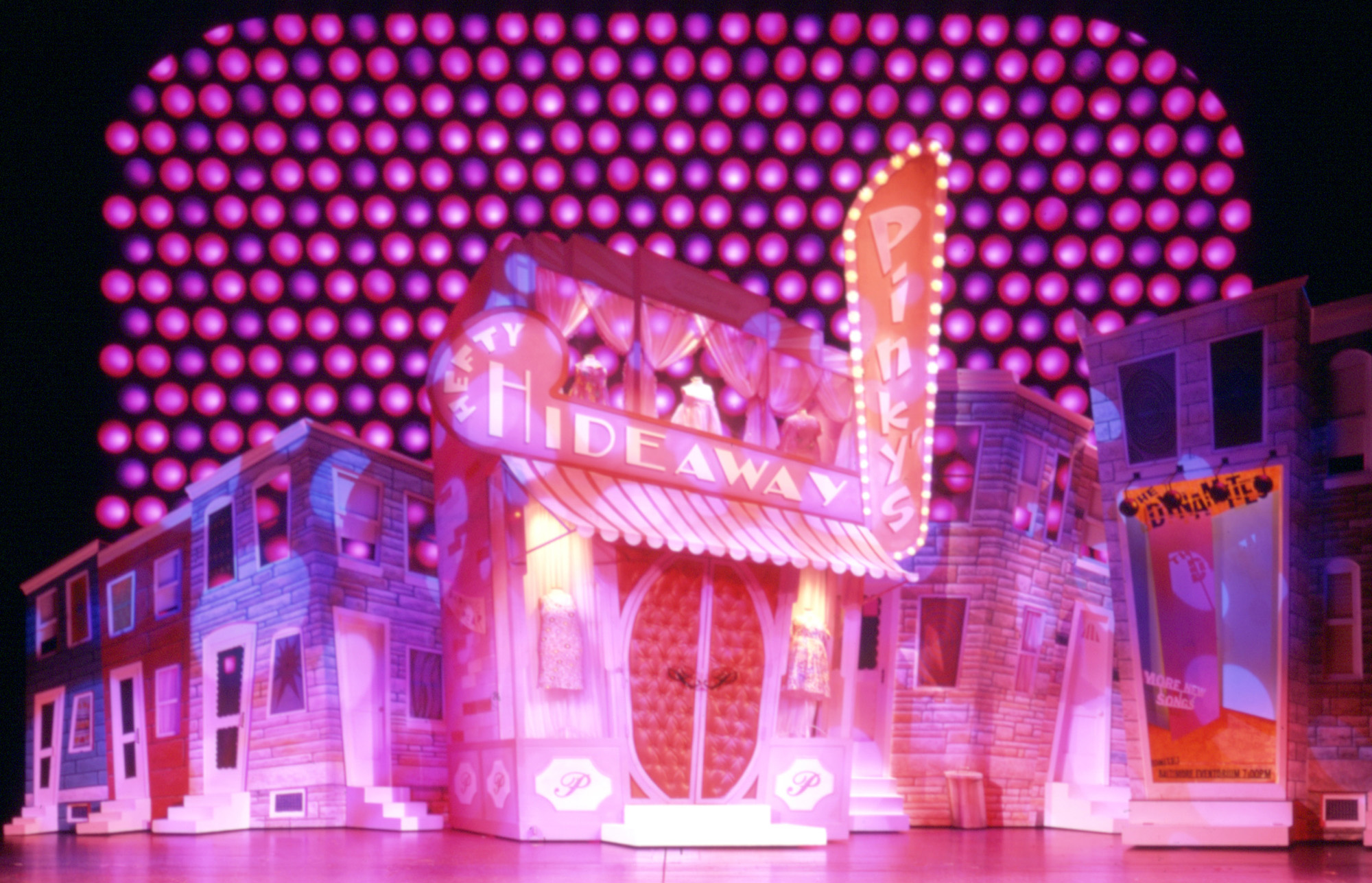

2002 Broadway production of Hairspray

There’s an element of realism to his designs and a keen awareness of movement that sets him apart from his contemporaries. Moreover, the audience is often let in on the scenic transitions that happen in a production he works on. For his Tony Award-winning set design for the 2016 production of She Loves Me, a musical set in a 1930s-era perfume shop in Budapest, Rockwell created an art nouveau-style building that opened like a jewel box.

‘Architects have a great visual and three-dimensional awareness of space, and not all theatrical designers work in that way,’ says Sladen. ‘They might work from a sketch of a visual picture or they might start with colour palettes. From the beginning, David is always thinking, “How is this going to work?”’

2018 Broadway production of The Nap

In Kinky Boots, a realistic-looking factory floor was transformed into a fantasy world using a change in lighting and by converting a conveyor belt into multiple moving treadmills on which the actors danced. ‘The models were critical for studying how things could rotate in space and how dance might integrate with that,’ says Rockwell. ‘You can’t really study it any other way than with a model; they don’t misrepresent the truth. In renderings, you can convince yourself of a lot of realities.’

Set models represent the private conversations between a stage designer and a production’s director, lighting designer, choreographer and costume designer. They are also kept on hand at rehearsals, allowing actors to build their characters, and are continually modified as they perfect their movement across the stage. Unlike models for buildings, which are designed to be displayed, set models are workhorses that the public never sees. Because of this, a model becomes ‘a little bit like the playbill’, Rockwell says. ‘It’s a collection of memories.’

2013 Broadway production of Kinky Boots

Rockwell himself is a student of other theatre designers’ models, especially those of Boris Aronson, who designed the original set for Fiddler on the Roof. Aronson’s widow gifted Rockwell an original set model for the Tony-winning 1971 production of Company, which sits in his office. He’s also a frequent visitor to the Lincoln Center branch of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, one of the few locations that publicly displays theatre set models. Sadly, few wind up in collections because they rarely survive due to their delicate nature.

2002 Broadway production of Hairspray

The ephemerality of theatre makes the genre especially difficult to collect. But its material remnants, set models in particular, are particularly evocative objects. The V&A often hosts special tours for people with dementia, and its theatre collection is a favourite destination. ‘Visitors will see a set model or a costume or a poster for a musical and they’ll start singing,’ Sladen says. ‘They know the words perfectly because that memory is so strong.’

Rockwell appreciates that more people will now be able to see and experience the models he has made following their acquisition by the V&A. ‘I’m intrigued and honoured and terrified all at the same time because they’re objects I love having,’ he says. ‘It’s sort of a step in letting go of the object, keeping the memory, and then being part of this collective memory.’

rockwellgroup.comvam.ac.uk

This article appears in the August 2024 issue of Wallpaper*, available to download free when you sign up to our daily newsletter; in print on newsstands; on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS;and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today

Diana Budds is an independent design journalist based in New York

-

MoMA celebrates African portraiture in a far-reaching exhibition

MoMA celebrates African portraiture in a far-reaching exhibitionIn 'Ideas of Africa: Portraiture and Political Imagination' at MoMA, New York, studies African creativity in photography in front of and behind the camera

-

How designer Hugo Toro turned Orient Express’ first hotel into a sleeper hit

How designer Hugo Toro turned Orient Express’ first hotel into a sleeper hitThe Orient Express pulls into Rome, paying homage to the golden age of travel in its first hotel, just footsteps from the Pantheon

-

These Kickstarter catastrophes and design duds proved tech wasn’t always the answer in 2025

These Kickstarter catastrophes and design duds proved tech wasn’t always the answer in 2025Odd ideas, Kickstarter catastrophes and other haunted crowd-funders; the creepiest, freakiest and least practical technology ideas of 2025

-

Wallpaper* USA 400: The people shaping Creative America in 2025

Wallpaper* USA 400: The people shaping Creative America in 2025Our annual look at the talents defining the country’s creative landscape right now

-

Pierre Yovanovitch’s set and costumes bring a contemporary edge to Korea National Opera in Seoul

Pierre Yovanovitch’s set and costumes bring a contemporary edge to Korea National Opera in SeoulFrench interior architect Pierre Yovanovitch makes his second operatic design foray, for The Marriage of Figaro in Seoul

-

‘As soon as I feel like somebody has worked me out, I want to switch it up’: set designer Shona Heath on staying authentic in a digital age

‘As soon as I feel like somebody has worked me out, I want to switch it up’: set designer Shona Heath on staying authentic in a digital ageShona Heath reflects on her 2024 Oscar win, being named a Royal Designer for Industry and the importance of dreaming

-

‘Air Play Moon Safari’ is an audio-visual, retro-futuristic experience

‘Air Play Moon Safari’ is an audio-visual, retro-futuristic experienceWith the ‘Air Play Moon Safari’ tour in full swing across Europe, the USA and Mexico for the rest of 2024, we explore the design of the French band's White Box stage

-

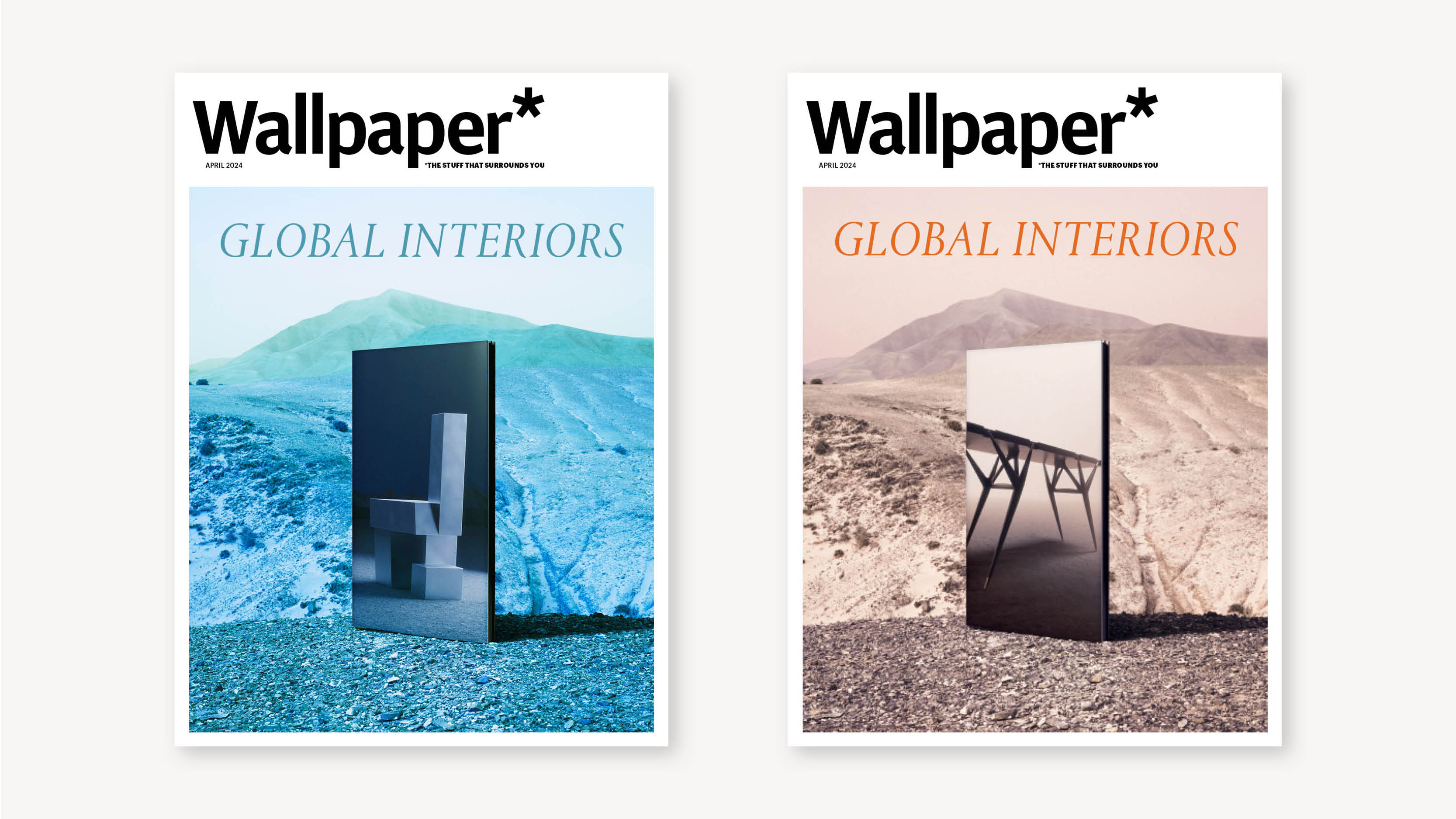

Introducing Wallpaper* April 2024: Global Interiors

Introducing Wallpaper* April 2024: Global InteriorsTake a global tour of contemporary design with Wallpaper* April 2024, from a Manhattan ‘cathedral of fried chicken’ to a Mornington Peninsula beach house. On sale now

-

BAFTA 2024 stage design pays tribute to the history of film animation

BAFTA 2024 stage design pays tribute to the history of film animationThe 2024 BAFTA Film Awards celebrated the best of the past year’s films, with an elegant stage by Yellow Studio, which pays tribute to the history of film animation

-

Ambika Hinduja collaborates with Edelweiss to create a baby grand piano inspired by autumn foliage

Ambika Hinduja collaborates with Edelweiss to create a baby grand piano inspired by autumn foliageAmbika Hinduja’s ‘Harmony of Nature - A Concerto of Art’ has been unveiled at the Victoria and Albert Museum

-

David Rockwell’s 2021 Oscars set design celebrates old Hollywood

David Rockwell’s 2021 Oscars set design celebrates old HollywoodStaged within Los Angeles' Art Deco Union Station, the David Rockwell-designed Oscars 2021 set nods to old Hollywood and the communal arts