Ido Yoshimoto turns salvaged wood into sculptural pieces at his northern Californian workshop

Visiting Ido Yoshimoto at his California studio, we talk to the artist about his work with wood, from his beginning as an arborist to his sculptures and furniture made with local reclaimed material

For sculptor Ido Yoshimoto (featured in 2024’s Wallpaper* USA 400, our guide to creative America), making art is a way to figure out how things work, and how to fix what is broken. Sometimes it’s just repairing an old pepper grinder or cleaning a fish. But it’s also about living as nature, not with nature, an expression of curiosity and connection. Making art makes the world feel less mysterious because it’s tinkering in its highest form.

Visiting Ido Yoshimoto in Inverness, California

Yoshimoto’s workshop consists of two shipping containers covered by a translucent fibreglass canopy

Yoshimoto – whose former work as an arborist lies at the root of his practice – salvages wood, ranging from cedar, walnut and cypress to old-growth redwood downed by disaster or age. Local arborists, millers and friends report finds to him and help tow them to his workshop, near the small Californian town of Point Reyes Station in Marin County. For more than a decade, he has used these finds to create seating, sculptural walls, footed bowls, artwork, desks and headboards. He also works with gallerists, private clients, architects and interior designers, including Nicole Hollis, Commune Design, and Charles de Lisle, for whom he crafted a patchwork residential façade and tables for the cocktail bar at the Sea Ranch resort on the northern California coast.

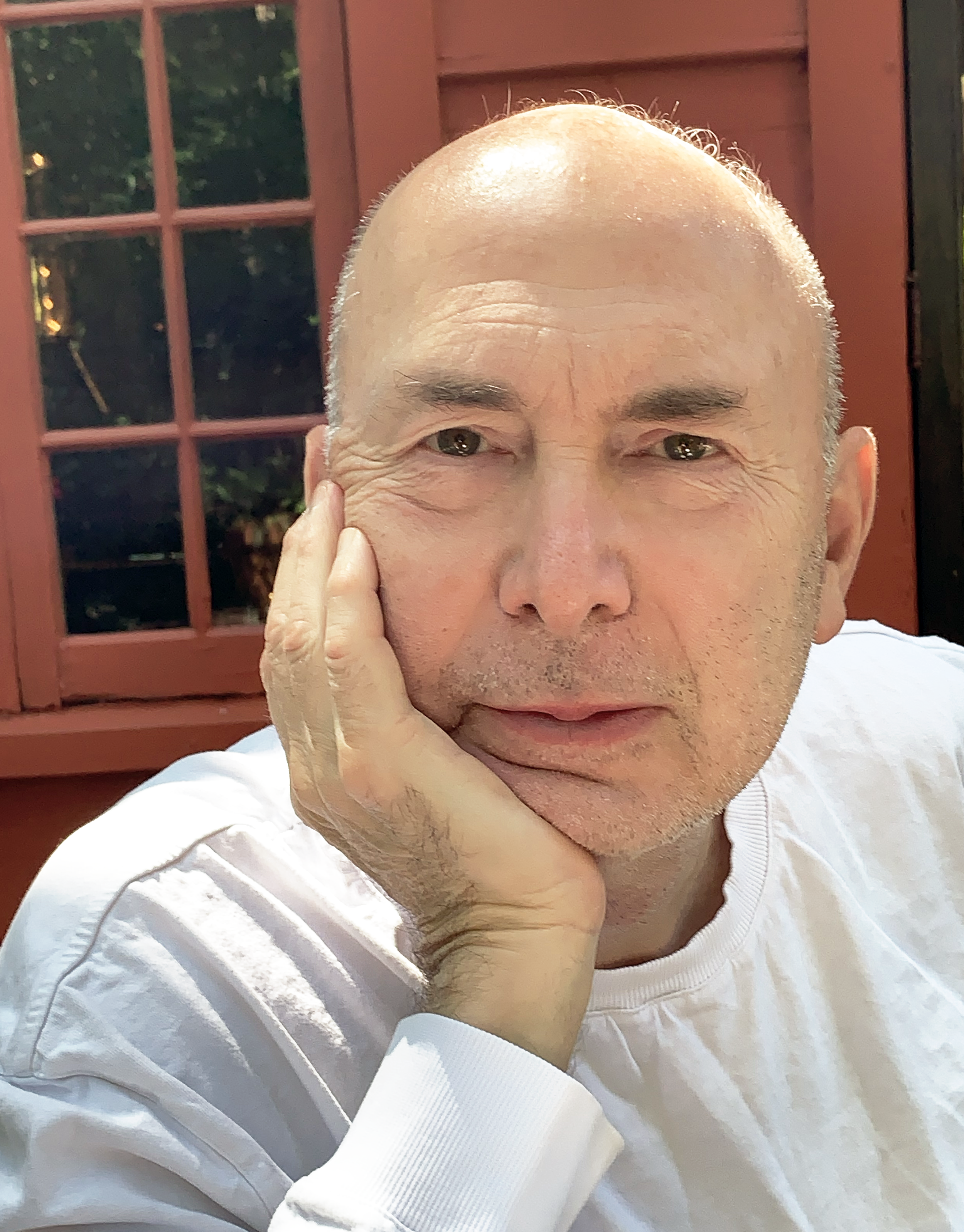

Yoshimoto at his studio with a cedar block waiting to be carved

Surrounded by golden hills, birdsong and the lowing of cows, Yoshimoto’s sheltered but mostly outdoor workshop consists of two shipping containers underneath a translucent fibreglass canopy. One container holds maquettes, sketches pinned to corkboard, and finished work. The other holds tools, such as chainsaws, clamps, bits, sanders, planers and massive mills for slabbing wood.

Pieces in progress sit on low platforms not far from a three-ton hoist. Partially cut and polished, but with its tangled roots untouched, one piece of redwood resembles a cresting wave flecked with foam. A coffee table made from driftwood pulled from nearby Tomales Bay at high tide pairs feral forms with a smooth, limpid top and crisp geometric cuts. Under its lacquer of oils and waxes, the grain looks as luminous as copper wire. Its flawless flatness adds a radical dimension, accenting this communion of the natural and man-made.

A redwood vase and sculpture made from salvaged redwood from Mendocino County and a redwood side table made from salvaged redwood from Humboldt County

Yoshimoto grew up locally, in Inverness, where he still lives with his wife and one of his daughters, just five miles from his workshop. His father, a sculptor and builder from the Hawaiian island of Oahu, arrived in 1977 to work with sculptor JB Blunk (soon to be Yoshimoto’s godfather).

Inverness was one of the Marin County communities whose inhabitants had turned away from the mainstream to live closer to nature, in smaller hamlets, leaving a smaller footprint on the earth. Yoshimoto had a mathematical mind and would break objects in order to learn how to fix them. As a child, life was idyllic: fishing, foraging for mushrooms, bonfires on the beach, camping out in cow fields, and shaping lumps of clay into animals in his dad’s studio.

A redwood coffee table made from salvaged redwood from Mendocino County

Everyone knew everyone and their DIY lives consisted of almost unconscious acts of ad hoc creativity. ‘Being an “artist” wasn’t such a big thing because everyone was creative in their daily lives,’ says Yoshimoto. ‘They applied “art” to everything they were doing.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Blunk, and many others, lived in houses they had built for themselves (his is now a museum). In these small homes, there may not have been room to display a sculpture, but there was room for a table, so the table – an ‘ordinary’ labour of love – became both. (Having leased a cabin from the local Nature Conservancy in 2017, Yoshimoto, object by object and structure by structure, has now built his own family’s home by hand, too.)

From arborist to artist

Yoshimoto outside the workshop

At 20, Yoshimoto went to work as an arborist. ‘Being paid to climb trees and swing around on ropes with chainsaws and cranes and rigging was a dream,’ he admits. But the job also turned into a 16-year master class in sculpture, honing the skills and esoteric knowledge needed to do the woodwork. Gradually, organically, the forest gave substance to his creativity.

The workshop with samples of wood ready to be carved

‘Wood is a wild lifeform, not just an organic material. It needs to be honoured,’ he says. ‘You can never master it, and that’s a humbling thing.’ Trees, living hundreds, even thousands, of years, chart the history of a single place over a vast span of time: rings record changes of season and climate; scars recall injuries (he once found a bullet and bullet hole); insect trails trace flourishing life or wasting disease. Uneven growth marks a sudden abundance (or lack) of light, while root systems hint at water sources, mineral-rich soil or abrasive winds. Yoshimoto also remembers where many of the trees he works with once stood. There is no other material like it.

A redwood side table made from salvaged redwood from Humboldt County

Blunk’s use of wood and tools (wielding a chainsaw to juxtapose coarse and flowing surfaces) was influential, but Yoshimoto has established his own methods. He takes great satisfaction in using off-the-shelf tools, but he also constructs his own jigs because, in keeping with his upbringing, why buy what you can make? This is also a way of pushing standard tools to create precise, elemental forms that feel unexpected and sublime.

Because he risks fraying, feathering or chipping the wood at every moment, doing this work with relatively simple tools lets him make intuitive decisions on the fly and allows the material to guide, or inspire, him. He sometimes even sculpts green timber or unstable wood, such as eucalyptus, letting the piece crack and warp later as it dries. This choice has the virtue, Yoshimoto says, of ensuring that the wood will always have the last word.

This article appears in the August 2024 issue of Wallpaper*, available to download free when you sign up to our daily newsletter, in print on newsstands from 4 July, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today

Yoshimoto working on a large piece of redwood

Shonquis Moreno has served as an editor for Frame, Surface and Dwell magazines and, as a long-time freelancer, contributed to publications that include T The New York Times Style Magazine, Kinfolk, and American Craft. Following years living in New York City and Istanbul, she is currently based in the San Francisco Bay Area.

-

‘I want to bring anxiety to the surface': Shannon Cartier Lucy on her unsettling works

‘I want to bring anxiety to the surface': Shannon Cartier Lucy on her unsettling worksIn an exhibition at Soft Opening, London, Shannon Cartier Lucy revisits childhood memories

-

What one writer learnt in 2025 through exploring the ‘intimate, familiar’ wardrobes of ten friends

What one writer learnt in 2025 through exploring the ‘intimate, familiar’ wardrobes of ten friendsInspired by artist Sophie Calle, Colleen Kelsey’s ‘Wearing It Out’ sees the writer ask ten friends to tell the stories behind their most precious garments – from a wedding dress ordered on a whim to a pair of Prada Mary Janes

-

Year in review: 2025’s top ten cars chosen by transport editor Jonathan Bell

Year in review: 2025’s top ten cars chosen by transport editor Jonathan BellWhat were our chosen conveyances in 2025? These ten cars impressed, either through their look and feel, style, sophistication or all-round practicality

-

Lost William Morris designs are being revived and completed for a new collection

Lost William Morris designs are being revived and completed for a new collectionWhen The Huntington in California discovered incomplete William Morris designs in its archive, the museum partnered with Morris & Co. to bring the them to life in 'The Unfinished Works'

-

New furniture from Maiden Home elevates elemental materials through unique design

New furniture from Maiden Home elevates elemental materials through unique designFinely crafted and exquisitely formed, the New York furniture brand’s latest designs find their perfect showcase at a modernist Californian home

-

Wallpaper* USA 400: The people shaping Creative America in 2025

Wallpaper* USA 400: The people shaping Creative America in 2025Our annual look at the talents defining the country’s creative landscape right now

-

Workstead's lanterns combine the richness of silk with a warm glow

Workstead's lanterns combine the richness of silk with a warm glowAn otherworldly lamp collection, the Lantern series by Workstead features raw silk shades and nostalgic silhouettes in three designs

-

Can creativity survive in the United States?

Can creativity survive in the United States?We asked three design powerhouses to weigh in on this political moment

-

Murray Moss: 'We must stop the erosion of our 250-year-old American culture'

Murray Moss: 'We must stop the erosion of our 250-year-old American culture'Murray Moss, the founder of design gallery Moss and consultancy Moss Bureau, warns of cultural trauma in an authoritarian state

-

‘You can feel their presence’: step inside the Eameses’ Pacific Palisades residence

‘You can feel their presence’: step inside the Eameses’ Pacific Palisades residenceCharles and Ray Eames’ descendants are exploring new ways to preserve the designers’ legacy, as the couple’s masterpiece Pacific Palisades residence reopens following the recent LA fires

-

2025’s Wallpaper* US issue is on sale now, celebrating creative spirit in turbulent times

2025’s Wallpaper* US issue is on sale now, celebrating creative spirit in turbulent timesFrom a glitterball stilt suit to the Eames House, contemporary design to a century-old cocktail glass – the August 2025 US issue of Wallpaper* honours creativity that shines and endures. On newsstands now