‘It is a collaborative adventure, not a service provision’: Ilse Crawford on design as a tool for advancement and enhancement

Designer Ilse Crawford, founder of Studio Ilse and a revered shapeshifter in the industry, reflects on design in 2025 and finds cause for optimism

We are living in a world of parallel realities. One of design’s greater strengths is its capacity to build bridges and forge connections, yet I am surprised how frequently we still find ourselves explaining that design is a verb, not a noun. Many people still think design means expensive shopping or a bit of a party trick. There is still a lack of understanding that design is about materialising and manifesting values. Design creates alternative realities, and it is a complex strategic process. We believe that design is a tool for building new and better models for life and living. When design works, it helps us to live healthier lives, physically and socially, mentally and environmentally.

The privilege of having had a studio [Studio Ilse] for more than 20 years is that we can see where design has really worked in our projects that have evolved and endured beyond initial hype. You get to become your own therapist, revisiting existing projects to watch, listen and learn. You understand how and why they work – and also when they don’t. We are fortunate that we have clients who come back to us decades after we have worked together to embark on new journeys. Robust relationships are everything in design. It is a collaborative adventure, not a service provision.

This year Cathay Pacific came back to us, more than a decade after we redesigned the blueprint for their airline lounges. Despite winning industry awards at the time, to us the greatest measure of success is when clients return. It was 2013 when we pitched our rather wildcard concept to a roomful of suits in Hong Kong. The idea was simple: that passengers want to feel grounded, comfortable, and cared for in an airline lounge. We made the case that making spaces where people can really relax before take-off, that are informal, on a human scale, and considerate would be a more relevant route to long-term loyalty than making them feel expensive.

When design works, it helps us to live healthier lives, physically and socially, mentally and environmentally.

Ilse Crawford

In the 12 years since, much has changed at Cathay, in airline travel, in Hong Kong and in life. It’s heartening to hear that people love our lounges and that our vote for primal values has paid off. Today, the lounges define Cathay’s brand, not just on the ground, but in the air, and in their service and experience across all touchpoints. We hear stories of people who go out of their way to fly Cathay and who take longer connections to spend more time in the lounges. The hospitality, generosity and care are self-evident and the brand feels powerful for its integrity as a result.

Achieving good design requires conviction and effort. Our clients at Cathay thought we were mad turning up for a meeting after an overnight flight with the cross-section of a lounge chair to demonstrate design integrity. Gradually, they understood that we were showing the importance of brand values being more than skin deep, and of messaging being more than marketing. Every brand today proclaims their values with virtue-signalling abandon; few brands stand up to closer scrutiny. As Albert King sang: ‘Everyone wants to go to heaven but no one wants to die.’ And this is what design can do: it brings values to life and makes them visible, felt, understood, trusted. Our fight to include ‘real’ materials and furniture with an in-built repair warranty, such as Vitsoe’s 620 lounge chair by Dieter Rams, also paid off. Of the lounges we designed first time round, there is little that needs refreshing.

Good clients have trust, courage and commitment: they trust the expertise of a designer to lead them through the process of design; they have the courage to ignore the rear view mirror and look at the horizon together instead; and they have the commitment to create something for themselves, not copy something else. The best clients understand that design is more like anthropology and psychology than fashion. It requires understanding needs, identifying possibilities and addressing both together at a systemic, rather than superficial level.

Robust relationships are everything in design. It is a collaborative adventure, not a service provision

Ilse Crawford

The bed manufacturer Hästens, is another client who understands the value of the long-term approach – it has been around for 172 years. In 2018 we launched the ‘Being’ collection for Hästens, using 100 per cent linen and hemp for their healthy, non-toxic, sustainable and durable properties. It doesn’t sound radical, but it was a significant departure within the high-end market, then focused on innumerable thread counts as a readable sign of luxury. Over time, ‘Being’ has become very successful as Hästens’ audience has become more familiar with both the language of sleep hygiene and the health and environmental impacts of the textile industry. We find increasingly that clients are interested in sustainability when it has consequences on personal health, and that this is a powerful means to behavioural change; what’s personal is political. Again, design can build bridges and our role as designers is to help people make more-informed decisions and choices.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Recently I was invited by Hästens to speak to 100 of their global salespeople in Bali. I love that the brand invests in educating its workforce about ideas, rather than focusing solely on short-term sales goals. One of Hästens’ most successful shops in Europe is a small store in Sommerach just outside Frankfurt. The manager has a guest house, and when he invites people to stay he asks them in advance how tall they are and how much they weigh so he can arrange the most appropriate bed for them. Guests get a hearty, organic breakfast in the morning and, surprise, surprise, they sell very well. Care and effort ignite passion. Striving for friction-free convenience is a red herring; our time and energy is better spent sharing why things are wonderful to others. Enthusiasm is contagious.

Care and effort ignite passion... Enthusiasm is contagious

Ilse Crawford

Many of the instances where I find optimism today are where care, effort and agility are evident. The general manager of our hotel in Bali, which was part of a ‘luxury’ group, was a case in point. He recognised early on in his role that in order to turn a good experience into something extraordinary, he had to find a way to empower his team on the ground. He worked the system by increasing room rates in order to provide better service and a better experience overall, including giving his team an allowance that could be spent at their discretion on each guest in any moment where something might be needed to improve or mitigate a situation. This model allows him to train his staff to be alert, careful, responsive and, crucially, able to make decisions for themselves. The effect was palpable – the experience of being in a hotel where people genuinely care about you is incredible. I find it fascinating that this young GM changed the formula to turn top-down management into grassroots care – he understood the system. This is design in action.

Too much of life is governed only by what can be measured. The misunderstanding that design is synonymous with luxury shopping means we sometimes get approached for private equity funded projects by teams who believe that good design is a look, a formula that can be replicated, and that success is just a question of choosing the right chairs. The commodification of everything is one of our greatest societal ills in the West. The Excel spreadsheet has a lot to answer for. There are no lines for care, comfort, trust, soul, dignity, generosity, resourcefulness. We call these ‘The Unmeasurables’ and they are our studio’s design language. If we are unable to help a client understand why these qualities are vital then we cut our losses. We don’t underestimate the courage that is required by a client to trust us. Increasingly, we recognise that without this courage and trust, the shared commitment to follow through the design process and produce outstanding work is near-impossible.

The commodification of everything is one of our greatest societal ills. The Excel spreadsheet has a lot to answer for. There are no lines for care, comfort, trust, soul, dignity, generosity, resourcefulness. They are our studio’s design language.

Ilse Crawford

Meanwhile, in the studio, we think about how we can ‘elevate the elemental’, by which we mean prioritising the tactility of the things we touch daily, optimising natural light and celebrating natural materials to support humane experiences. When our lives feel too complex and chaotic to fathom, it makes sense that we go to the earth and the elements to feel alive again.

When people say that design is only for rich people, I tell them about Refettorio Felix, the project we did with Massimo Bottura’s Food for Soul non-profit organisation. We designed a community kitchen and social dining room for people living in vulnerable conditions. As good design often does, the project uses one problem to help solve another: in this case, food waste in support of social inclusion. The brief we developed together was to design for dignity. A great number of our regular collaborators and suppliers donated furniture, lighting, paint and textiles. The majority of people want to do good things. I take comfort from this simple fact, however torturous the rubric of our public institutions may be.

When our lives feel too complex and chaotic to fathom, it makes sense that we go to the earth and the elements to feel alive again

Ilse Crawford

So often the support for those who need care more than most is devoid of any warmth. How did we get to this version of reality? Regulations and de-risking often serve as the rationale to eliminate humanity. Nobody has to put their feelings on the line. There is frequently a lack of accountability and responsibility, and no room for genuine care. The consequences of this systemic de-risking are terrifying.

We have projects on the horizon in places where we haven’t worked before, and they are exciting. Social, economic and political change is happening in the East and global south and I’m fairly sure we will be left behind in the West. The current culture of economic colonialism and careless consumption are not the future. It is not right to romanticise craft, but there is a link between cultures where craft and generational skills exist still as an embedded part of life, and the viability of using design to create healthy systems that work for all involved: the people who make and the people who use; the resources and the processes; the earth and the environment. There is an increasing appreciation of local resources, skills and jobs. And an increasing number of individuals who are prepared to invest in them.

In these contexts there tends to be an inherent inter-connectedness that supports design. Technology can turn local case studies into powerful circular economic models – ones that inspire others to do things differently. Away from our frequent fairs and glamorous showrooms, design as a tool for positive change flourishes. As designers, we are privileged to cross between parallel realities, and I find design’s impact and embrace in these instances both hopeful and hope-filled.

A version of this article appears in the February 2025 issue of Wallpaper* , available in print on international newsstands, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today.

-

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’Wallpaper* takes a tour of Extreme Cashmere’s new Amsterdam store, a space which reflects the label’s famed hospitality and unconventional approach to knitwear

By Jack Moss

-

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the best

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the bestBrands including Bremont, Christopher Ward and Grand Seiko are exploring the possibilities of titanium watches

By Chris Hall

-

Warp Records announces its first event in over a decade at the Barbican

Warp Records announces its first event in over a decade at the Barbican‘A Warp Happening,' landing 14 June, is guaranteed to be an epic day out

By Tianna Williams

-

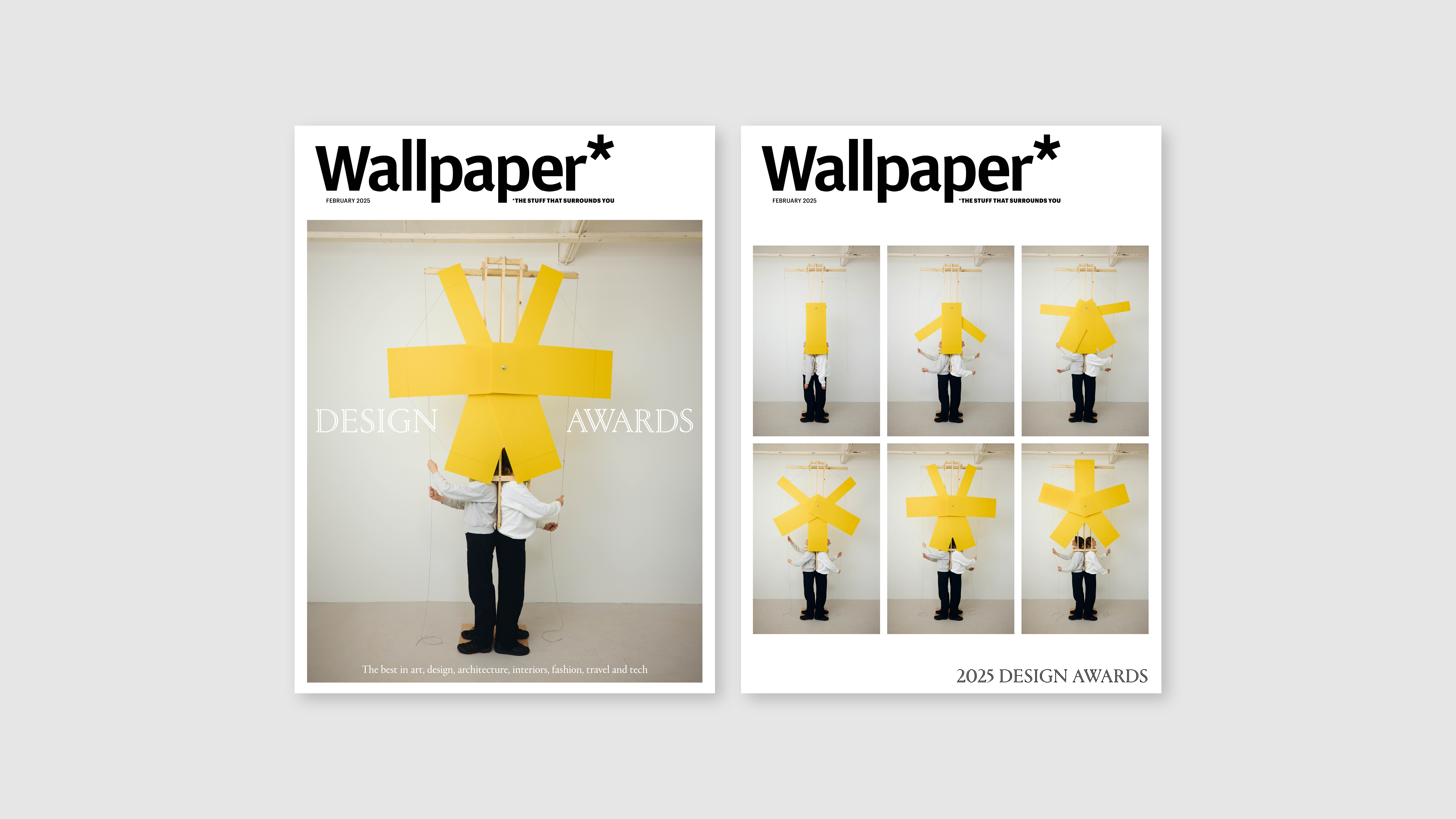

Wallpaper* 2025 Design Awards issue is on sale now – and full of star turns

Wallpaper* 2025 Design Awards issue is on sale now – and full of star turnsWelcome to the Wallpaper* 2025 Design Awards issue; get your copy to discover the best in design, fashion, technology, architecture, interiors, travel and art

By Bill Prince

-

Ilse Crawford brings humanistic design to Edelman's leather offering

Ilse Crawford brings humanistic design to Edelman's leather offeringIlse Crawford brings her vision to Edelman, starting with a rework of the brand’s three signature lines

By Jasper Spires