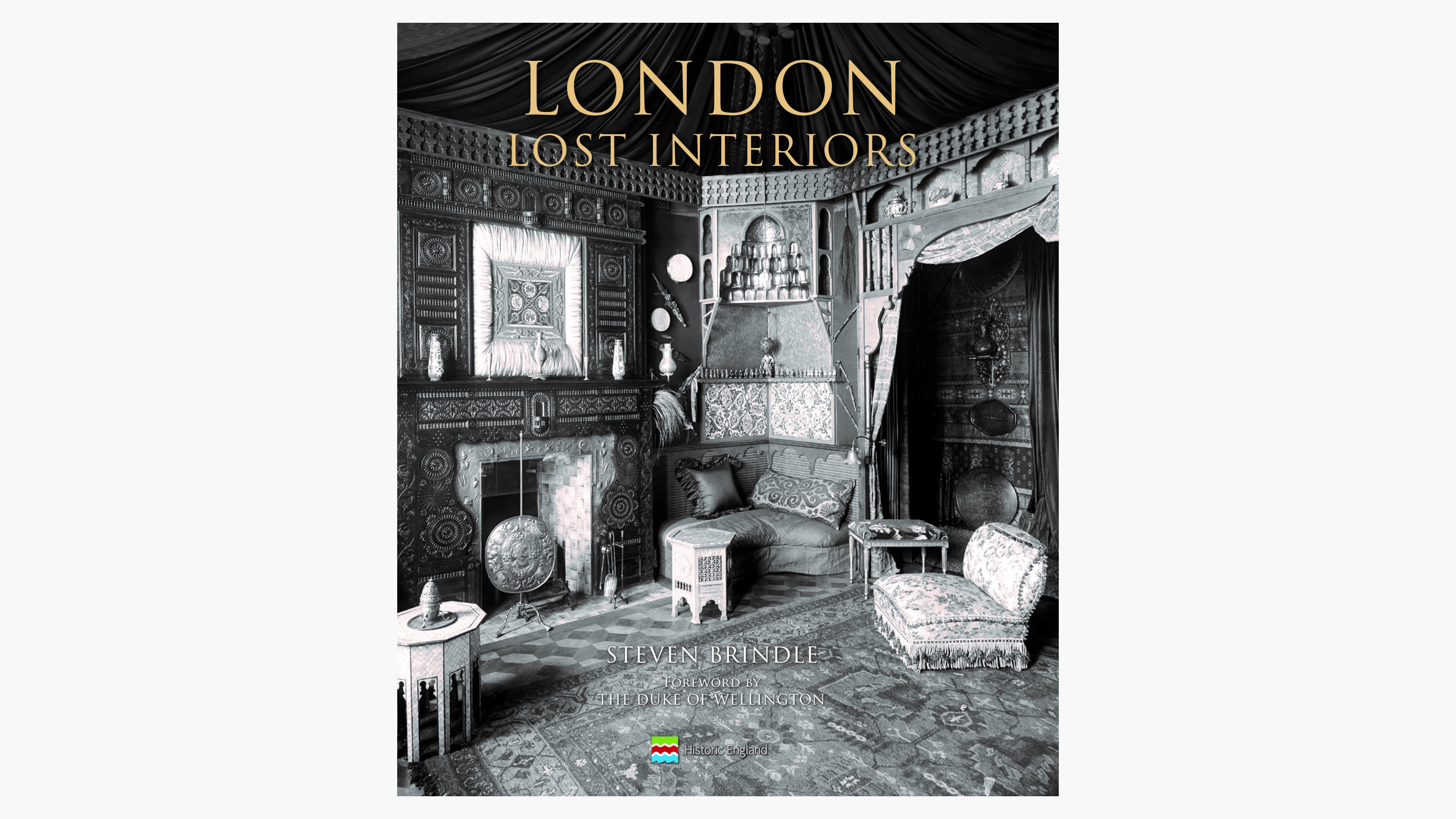

‘London: Lost Interiors’ gathers unseen imagery of some of the capital’s most spectacular homes

This new monograph is a fascinating foray into the interior life of London, charting changing tastes, emerging styles and the shifting social history of grand houses in the heart of a fast-changing city

Nostalgists will enjoy this latest book from Atlantic Publishing, specialist purveyor of monographs charting the photographic remnants of British heritage. London: Lost Interiors, written by historian Steven Brindle, relies on several expansive but little-seen photography archives, including the hugely valuable records created by Country Life and the RIBA.

54 Mount Street in Mayfair, the home of Robert Windsor Clive, Earl of Plymouth

Other sources are not so widely published, like the work of Bedford Lemere & Company, once the UK’s leading architectural photographer. The firm, which was in business from 1839 to 1911, left an archive 21,800 glass-plate negatives and 3,000 prints, all of which were acquired by the Historic England Archive in 1955.

35 Wimpole Street, Marylebone, home of arts patron Edward James and his ballerina wife, Tilly Losch. The bathroom, with fluoresecent tube lighting, was designed by Paul Nash

Brindle has also been able to draw on other important photographers, including Newton & Company and Millar & Harris, another firm regularly commissioned to chronicle new architecture for publications like Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. Sifting through this embarrassment of architectural riches, Brindle has shaped a fine monograph that charts the ultimate result of in constantly changing tastes: all these interiors have been lost.

5 Connaught Place, W1, home of Commander Edward Heywood Lonsdale RN, designed by Serge Chermayeff. A Picasso is placed prominently in the frame

That reality lends an elegiac quality to these purely black and white pages, which have been arranged to explore, variously, the world of aristocrats and plutocrats, the evolution of art deco and modernism, and, perhaps most heartbreakingly of all, the rare forays into interior design by true eccentrics and aesthetes.

The latter category is probably overshadowed by palatial staterooms, grand staterooms and ornate plasterwork that runs from Georgian London through to the overstuffed aesthetic of the Victorian treasure house. Not all of these have been destroyed, even if the interiors are no longer with us, but the vast majority have been the casualty of development in some form or another, if not enemy bombs.

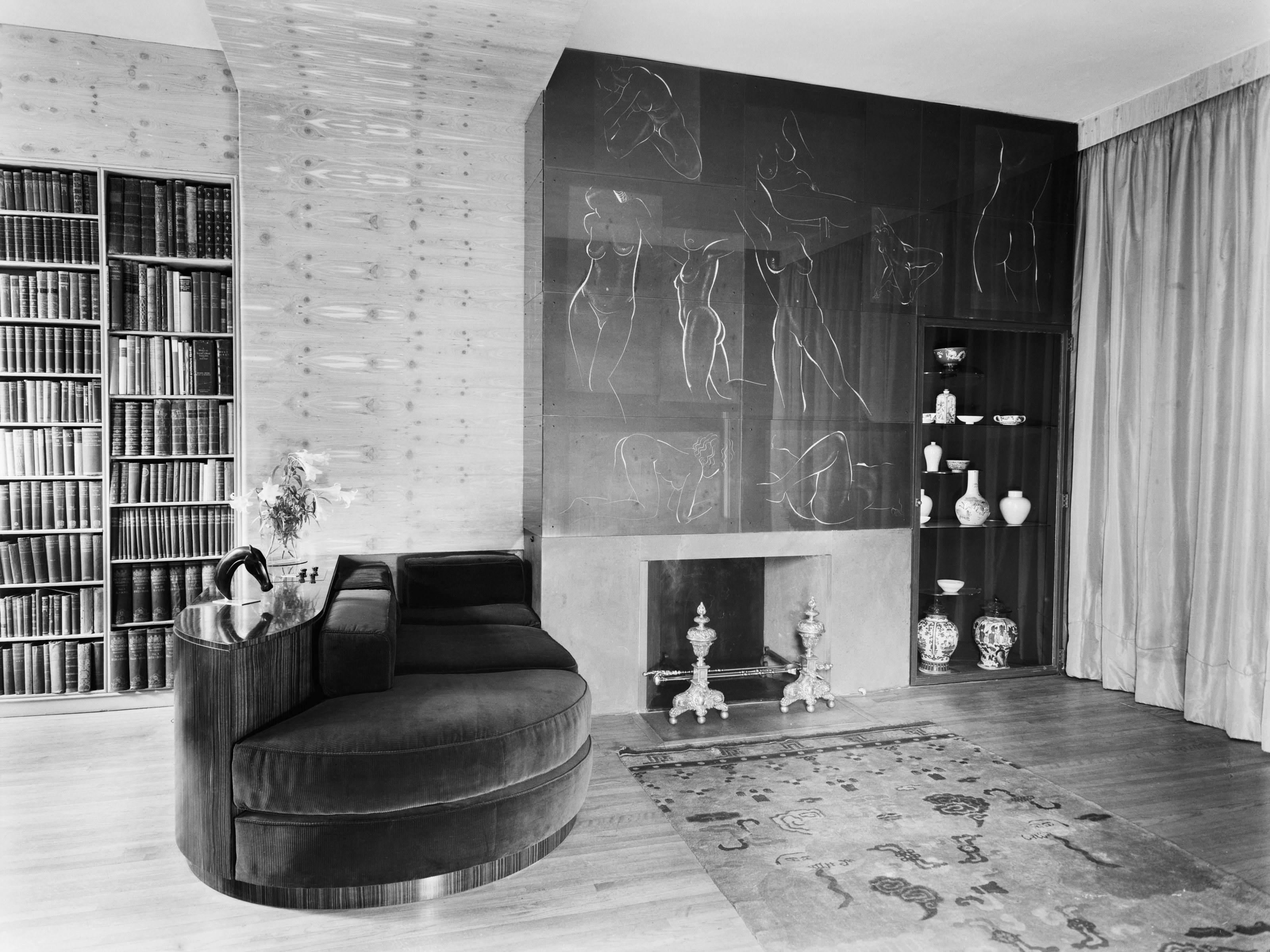

35 Cliveden Place, Belgravia, SW1, the home of architect Oliver Hill. The figures above the fireplace were engraved by Eric Gill

The book serves as a useful social and architectural history, as well as a primer on what defined taste and distinction in upper class interiors. So many of the capital’s ‘grand houses’ were lost to redevelopment, as the space taken up by mansions and their grounds became swallowed up by the expanding city. Other buildings have been repurposed as clubs or casinos or ‘lost’ into secretive private ownership, meaning these images are the only way we can revisit their interiors.

18 Yeoman’s Row, Chelsea, SW3, home of pioneering modernist architect and designer Wells Coates

The roll call of featured designers and artists is an impressive one, including William Morris, Sir Edwin Lutyens, Sibyl Colefax, Marion Dorn, Liberty, Serge Chermayeff, Philip Webb, Rex Whistler, Paul Nash and Detmar Blow, amongst others. The erstwhile owners are no less grand, including a large swathe of the Royal family, as well as film stars like Fay Wray and Greta Garbo, and even JFK.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Even the more prosaic is covered: the kitchen at flat 14, 7 Princes Gate, Knightsbridge, SW7, home of Mrs Vernon Tate

Although the book covers the period from around 1880 to the Second World War, we've focused especially on the work created in the 1920s and 1930s, when deco briefly became the style du jour. All in all, there are 650 images within the book's pages, chronicling every conceivable facet of the capital’s grandest, quirkiest and above all forgotten residential design.

London: Lost Interiors, Steven Brindle, with a foreword by the Duke of Wellington, Atlantic Publishing in association with Historic England, £50, AtlanticPublishing.co.uk, HistoricEngland.org.uk, Amazon.co.uk

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.

-

Eight questions for Bianca Censori, as she unveils her debut performance

Eight questions for Bianca Censori, as she unveils her debut performanceBianca Censori has presented her first exhibition and performance, BIO POP, in Seoul, South Korea

-

How to elevate a rental with minimal interventions? Charu Gandhi has nailed it with her London home

How to elevate a rental with minimal interventions? Charu Gandhi has nailed it with her London homeFocus on key spaces, work with inherited details, and go big on colour and texture, says Gandhi, an interior designer set on beautifying her tired rental

-

These fashion books, all released in 2025, are the perfect gift for style fans

These fashion books, all released in 2025, are the perfect gift for style fansChosen by the Wallpaper* style editors to inspire, intrigue and delight, these visually enticing tomes for your fashion library span from lush surveys on Loewe and Louis Vuitton to the rebellious style of Rick Owens and Jean Paul Gaultier

-

How to elevate a rental with minimal interventions? Charu Gandhi has nailed it with her London home

How to elevate a rental with minimal interventions? Charu Gandhi has nailed it with her London homeFocus on key spaces, work with inherited details, and go big on colour and texture, says Gandhi, an interior designer set on beautifying her tired rental

-

The Stuff That Surrounds You: Inside the home of designer Michael Anastassiades

The Stuff That Surrounds You: Inside the home of designer Michael AnastassiadesIn The Stuff That Surrounds You, Wallpaper* explores a life through objects. In this episode, we step inside one of the most considered homes we've ever seen, where Anastassiades test drives his own creations

-

Francis Sultana and Roberto Ruspoli’s Greco-Roman-inspired furniture feels fresh and contemporary

Francis Sultana and Roberto Ruspoli’s Greco-Roman-inspired furniture feels fresh and contemporaryA new collection, launching at David Gill Gallery in London, presents furniture and decorative pieces inspired by Mediterranean villas, French art and Etruscan engraving

-

The new office of the Italian embassy in London is a love letter to the country’s creativity

The new office of the Italian embassy in London is a love letter to the country’s creativityWallpaper* takes a peek inside Casa Italia, the new Italian embassy in London, designed by our long-time collaborator Nick Vinson

-

Sophie Smallhorn’s plywood tables for Uncommon Projects are colourful and modular

Sophie Smallhorn’s plywood tables for Uncommon Projects are colourful and modularThese modular tables by the artist and the plywood specialist play with colour for function, fun and flexibility

-

A new coffee table book proves that one designer’s trash is another’s treasure

A new coffee table book proves that one designer’s trash is another’s treasureThe Rizzoli tome, launching today (16 September 2025), delves into the philosophy and process of Retrouvius, a design studio reclaiming salvaged materials in weird and wonderful ways

-

Welcome to Salt, a London hair salon-turned-immersive audio experience

Welcome to Salt, a London hair salon-turned-immersive audio experienceStyling meets sound design at Salt’s second London outpost, a high-concept space by Unknown Works designed to be heard as much as seen

-

Step inside a neoclassical-inspired apartment in The Whiteley’s clock tower

Step inside a neoclassical-inspired apartment in The Whiteley’s clock towerSituated within London’s former Whiteleys department store, this newly unveiled residence combines Italian elegance, courtesy of furnishings by Maxalto, with architectural heritage