Joe Armitage's new chandelier and lamps are an enlightening take on a family heirloom

Designer Joe Armitage follows his grandfather’s footsteps in India, reissuing his elegant midcentury lamp and creating a new chandelier for Nilufar Gallery

For some of us, family inheritances tend to be burdensome, taking up space, emotionally and physically, in both our minds and attics. For the London-based designer and architect Joe Armitage, however, a family heirloom has taken him somewhere lighter and brighter, across generations and continents, and into the path of Le Corbusier. This is the story of a lamp designed by Edward Armitage in India 72 years ago, which has today been expanded into a collection of lights by his grandson Joe.

The story behind Joe Armitage's ‘Noveconi’ chandelier

‘My great-grandfather, Joseph Armitage, was a stone carver from Yorkshire, who worked in London from 1910 onwards,’ explains Armitage. He made decorative stonework for buildings like the Bank of England and Windsor Castle, and also for Lutyens’ parliament buildings in New Delhi. This was the start of the Armitage family bond with India, which would strengthen significantly in the next generation.

Following India’s partition in 1947, the Indian government decided to build a new city, Chandigarh, as the Punjabi capital. Le Corbusier and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret were commissioned to design a city for the future, and they asked British architects Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew to help them with some of the housing and administrative buildings. ‘One day, Fry broke his wrist and was transferred to the nearest hospital, in Ludhiana, where he was asked if he could also design a new hospital for them,’ says Armitage. ‘Fry replied that he didn’t have the capabilities, but he knew someone who could. He called my grandfather, Edward, who was in his twenties at the time. His 21-year-old wife, Marthe, had just given birth to my father, but they moved to India and took on the project. My grandmother is still alive and talks fondly about those two incredible years in India.’

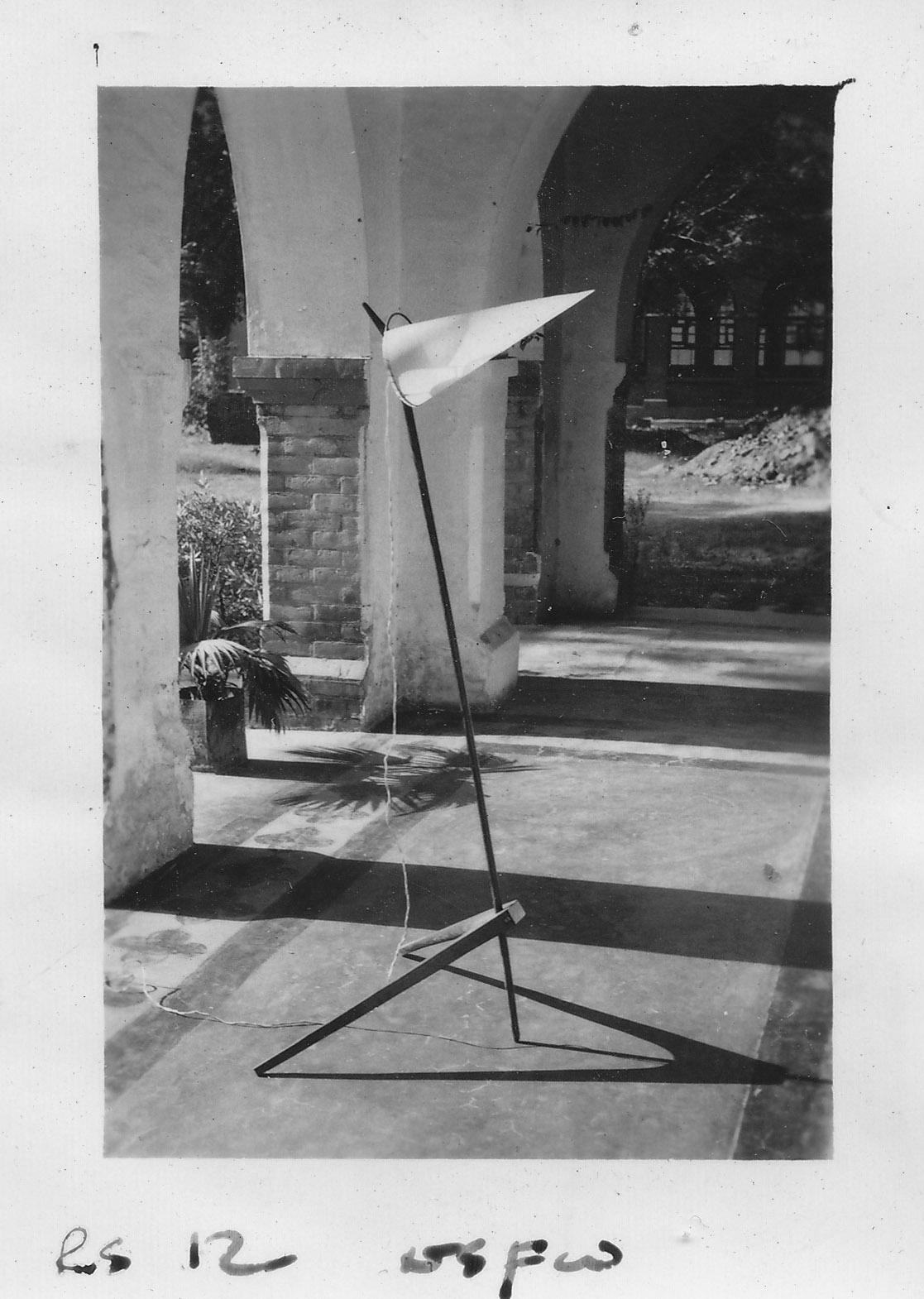

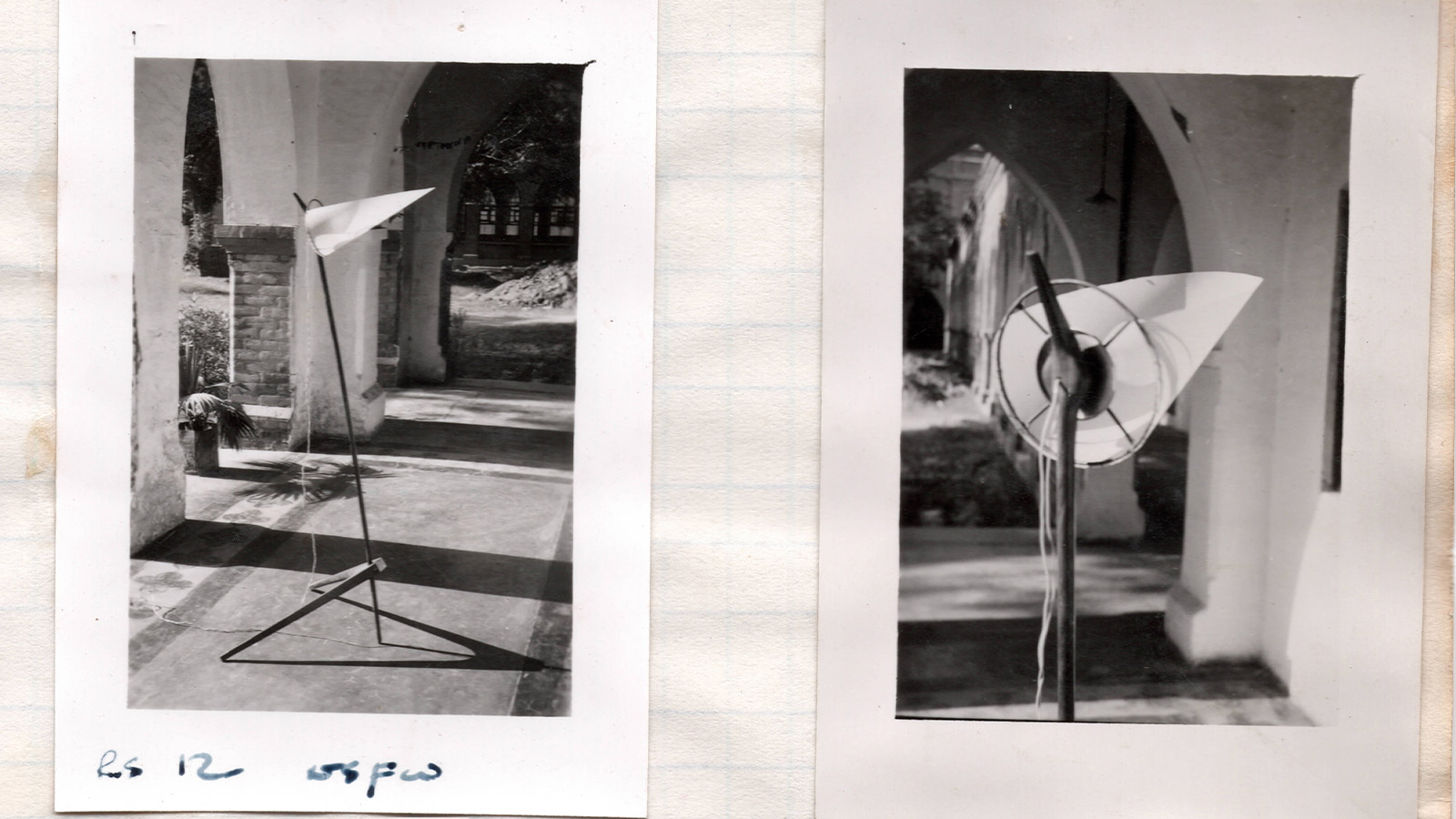

An archive photograph of the original Armitage floor lamp, taken by Edward Armitage

Edward designed furniture that included chairs, tables, a desk, a music stand, and a bedside table because, as part of the hospital complex, he was also responsible for designing the guesthouses and houses for the doctors. This is where the lamp originated. ‘Resources were scarce, so the ring at the back of the lamp was an old paint tin, attached to four motorbike spokes, and the shade was just paper, sewn to the ring,’ explains Armitage.

Armitage wonders if the couple’s sea voyage from London to Mumbai may have subliminally influenced the design of the cone, which looks like a windsock or a sail, he says, pointing at an old photograph taken from the steamship. Black and white photographs document the Armitages’ lives during their time in India, but there were no technical sketches of the lamp. To recreate it, Armitage began with the original and carefully followed anthropological clues and cues. The arching rosewood stem is anchored in a V-shaped base, echoing the legs of Pierre Jeanneret’s ‘Chandigarh’ chair from the same wave of post-war modernism in India.

The ‘Armitage’ floor lamp and desk lamp are now made of walnut and recycled PET plastic, rather than the original rosewood and paper

Armitage never met his grandfather, but it is thanks to his 94-year-old grandmother, Marthe – a globally renowned wallpaper designer and hand-block printer – that the story continues. ‘The original lamp is still in her living room. She once hosted a large group of press and buyers for tea. Someone saw the lamp and asked about it. The next day, she said to me, “I have 20 orders for that old lamp. Could you make them?” And that’s how I got into lamps,’ he laughs. Today, the ‘Armitage’ lamp collection includes floor, desk, wall, accent and suspension lamps, all sharing the signature conical shade of their forebear.

‘The original one was in paper, but I developed a kind of recycled PET from water bottles that looks like Japanese washi paper,’ says Armitage. ‘It is translucent and durable and gives a soft, warm glow.’ He also redesigned the ring in solid brass and installed a modern dimmable LED bulb. His grandfather’s version was made from rosewood, which is now endangered, so Armitage’s reissues are made from walnut.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The reissued ‘Armitage’ lamp is also available as a sconce, photographed here in Le Corbusier’s 1954 ATMA house in Ahmedabad, Gujarat

The most recent addition to the family of lights is the ‘Noveconi’ chandelier, designed by Armitage for Nilufar Gallery together with a wall sconce and ceiling lamp. Nilufar will show them in Mumbai later this year during the Milanese gallery’s inaugural exhibition in the country. ‘The show is a mix of vintage works by the great masters of design and contemporary pieces,’ says Nilufar Gallery founder Nina Yashar. In addition to Joe Armitage’s lamps, the exhibition will feature pieces from Khaled El Mays, David/Nicolas and many more. It is a favourable moment for art and design in India, says Yashar: ‘I find that the Indian market is perfect for experimenting with these collections. This is the first time we are doing something in India, and I must say I am very proud of it. India is currently experiencing a golden moment for collectible design.’

Edward Armitage’s original floor lamp is also travelling back to India: Joe Armitage has donated the new version to the Ludhiana hospital, and for this story, we were granted access to Ahmedabad’s ATMA House, one of the finest existing examples of Le Corbusier’s domestic architecture in India, to photograph the pieces together before they disperse.

This article appears in the October 2024 issue of Wallpaper*, available in print on newsstands, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today.

Cristina Kiran Piotti is an Italian-Indian freelance journalist. After completing her studies in journalism in Milan, she pursued a master's degree in the economic relations between Italy and India at the Ca' Foscari Challenge School in Venice. She splits her time between Milan and Mumbai and, since 2008, she has concentrated her work mostly on design, current affairs, and culture stories, often drawing on her enduring passion for geopolitics. She writes for several publications in both English and Italian, and she is a consultant for communication firms and publishing houses.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

Inside the Shakti Design Residency, taking Indian craftsmanship to Alcova 2025

Inside the Shakti Design Residency, taking Indian craftsmanship to Alcova 2025The new initiative pairs emerging talents with some of India’s most prestigious ateliers, resulting in intricately crafted designs, as seen at Alcova 2025 in Milan

By Henrietta Thompson

-

'Now, the world is waking up': Vikram Goyal on bringing Indian craftsmanship to the global stage

'Now, the world is waking up': Vikram Goyal on bringing Indian craftsmanship to the global stageWe talk to Indian craft entrepreneur Vikram Goyal about redefining heritage, innovating with repoussé, and putting Indian craftsmanship on the global map.

By Ali Morris

-

‘The Indian market has come of age’: Inside Nilaya Anthology, India’s new design destination

‘The Indian market has come of age’: Inside Nilaya Anthology, India’s new design destinationNilaya Anthology – a global design showroom with a distinctly Indian perspective – has opened in Mumbai

By Ali Morris

-

This ethereal Chennai home is a celebration of Indian craft and culture

This ethereal Chennai home is a celebration of Indian craft and cultureDesigned by Multitude of Sins, this Chennai home is an artisanal trove of rich texture and secret garden-like design. Wallpaper* speaks with design principal Smita Thomas on crafting the space

By Tianna Williams

-

Indian furniture brand SĀR Studio is putting Pune on the map with a new flagship and residency programme

Indian furniture brand SĀR Studio is putting Pune on the map with a new flagship and residency programmeSĀR Residence, a multi-use concept space, acts as an extension of the Indian furniture brand

By Laura May Todd

-

Pierre Jeanneret and Edward Armitage: tracing design inspiration in Chandigarh

Pierre Jeanneret and Edward Armitage: tracing design inspiration in ChandigarhBritish designer Joe Armitage set off for Chandigarh, India, to trace his grandfather Edward’s footsteps and recreate a photograph of the latter’s ‘Armitage’ lamp. A trail of intrigue around its inspiration lay in wait, as he reveals

By Joe Armitage

-

It’s the first-ever Design Mumbai: here’s what to see

It’s the first-ever Design Mumbai: here’s what to seeAt least 100 international and Indian brands will showcase at Design Mumbai, referencing India’s rich and storied heritage of craftsmanship and highly specialised craft clusters (6-9 November 2024)

By Giovanna Dunmall

-

Pierre Jeanneret’s Chandigarh furniture meets South Asian diasporic art in an unusual London exhibition

Pierre Jeanneret’s Chandigarh furniture meets South Asian diasporic art in an unusual London exhibitionRajan Bijlani opens a show combining Pierre Jeanneret furniture for the Indian city of Chandigarh with works for sale by six artists of South Asian origin – in his own London townhouse

By Dal Chodha