‘If you’re a designer today, you have to keep learning to keep up’: curator Jane Withers

Jane Withers, curator of London Design Festival 2024’s Brompton Design District, on bringing learning to life at the event, and her drive to spark ecological debate

Jane Withers built her career at the intersection of design, sustainability, and environmental advocacy long before these issues became mainstream. Since founding her studio in 2001, she has collaborated with leading design brands, cultural institutions and global corporations to harness design as a tool for positive change. Trained in Art History at the Courtauld Institute and History of Design at the Royal College of Art/V&A, Withers wears many hats – journalist, curator, author, and self-confessed 'aquaholic' – with much of her work focused on water scarcity and bathing culture. We caught up with her ahead of London Design Festival 2024, where she will curate the Brompton Design District for the 16th consecutive year.

Jane Withers on the art of curation, and LDF 2024’s Brompton Design District

Left to right, Andu Masebo and Mikey Krzyzanowski will present 'The Making Room', ‘somewhere to absorb knowledge from a wide range of sources and learn tacitly through experience’, as part of Brompton Design District 2024

Wallpaper*: In the early days of your practice, did you feel like a lone voice in the design industry talking about environmental issues?

Jane Withers: Yes, particularly in relation to water scarcity. In 2008, when we did the exhibition ‘1% Water’ at Z33 gallery in Hasselt, Belgium, which explored the richness of water cultures, historically and today, we had a section called ‘reconnect’, looking at ideas and solutions to the escalating water crisis, and we had very little to put in it; we were rather scrambling for people who were bringing alternative water practices to life. But this year, with our ‘Water Pressure’ exhibition at MK&G, 80 per cent of the exhibition is this. Maybe a decade ago, [these projects] might have been considered very alternative, perhaps not taken so seriously. Now they're being trialled at scale in many cases. So it really has changed a lot, and that, in a way, is what gives me hope.

‘Reading Design’ by Grymsdyke Farm will present the results of a workshop, exploring the ‘processes of learning through design but also how we learn from each other, from the environment, and through making’

W*: How do you see your role as a curator?

JW: I love the curatorial process of constructing narratives and making exhibitions, but I don’t see exhibitions as an end in themselves, rather, they're a catalyst for sparking debate, nurturing an ecological consciousness. When you make an exhibition about water, you want people to think more deeply about it, to be challenged and get a sense of agency, because these changes need to happen through advocacy from the ground up. Governments don't do anything unless people care, so people have to feel empowered to demand change. But you also want people to connect to water emotionally and enjoy it. You have to care about an issue to engage with it.

'The Seas Are No Longer Dying' by Superflux, on view until 13 October 2024 as part of ‘Water Pressure: Designing for the Future’ an exhibition at MK&G in Hamburg, curated by Jane Withers Studio

W*: How do you remain focused and hopeful when the outlook can seem quite bleak?

JW: I’m inspired by the work that's going on to change the future. There are so many people putting energy into it; it's no longer just fringe practices. I have belief in human ingenuity and the tools and technologies that are now emerging. Of course, it could still go either way, but there's a moral obligation not to give up. We have to find hope.

Also from ‘Water Pressure: Designing for the Future’ at MK&G, A Mother Holding Her Two Sons, a photograph taken by LaToya Ruby, during the arrival of Barack Obama at Flint, Michigan, 4 May 2016

W*: You’ve been curating London Design Festival’s Brompton Design District since its inception in 2007. What’s your approach to its curation?

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

JW: We try to do Brompton with quite a light touch. It’s very different from a museum show, we're not curating every aspect of it, we're just giving people the space to bring their ideas to life. We work with South Kensington Estates to use their empty spaces and you never quite know what’s going to be available. It can be quite last mintue, so you have to be quite dexterous and inventive, but that’s part of the fun of it. In terms of audience, I think the problem with design is it’s quite an insular world compared to, say, fashion, but the rising generation of designers are much better at working with communities and understanding interaction. So I think that really is changing and that's good.

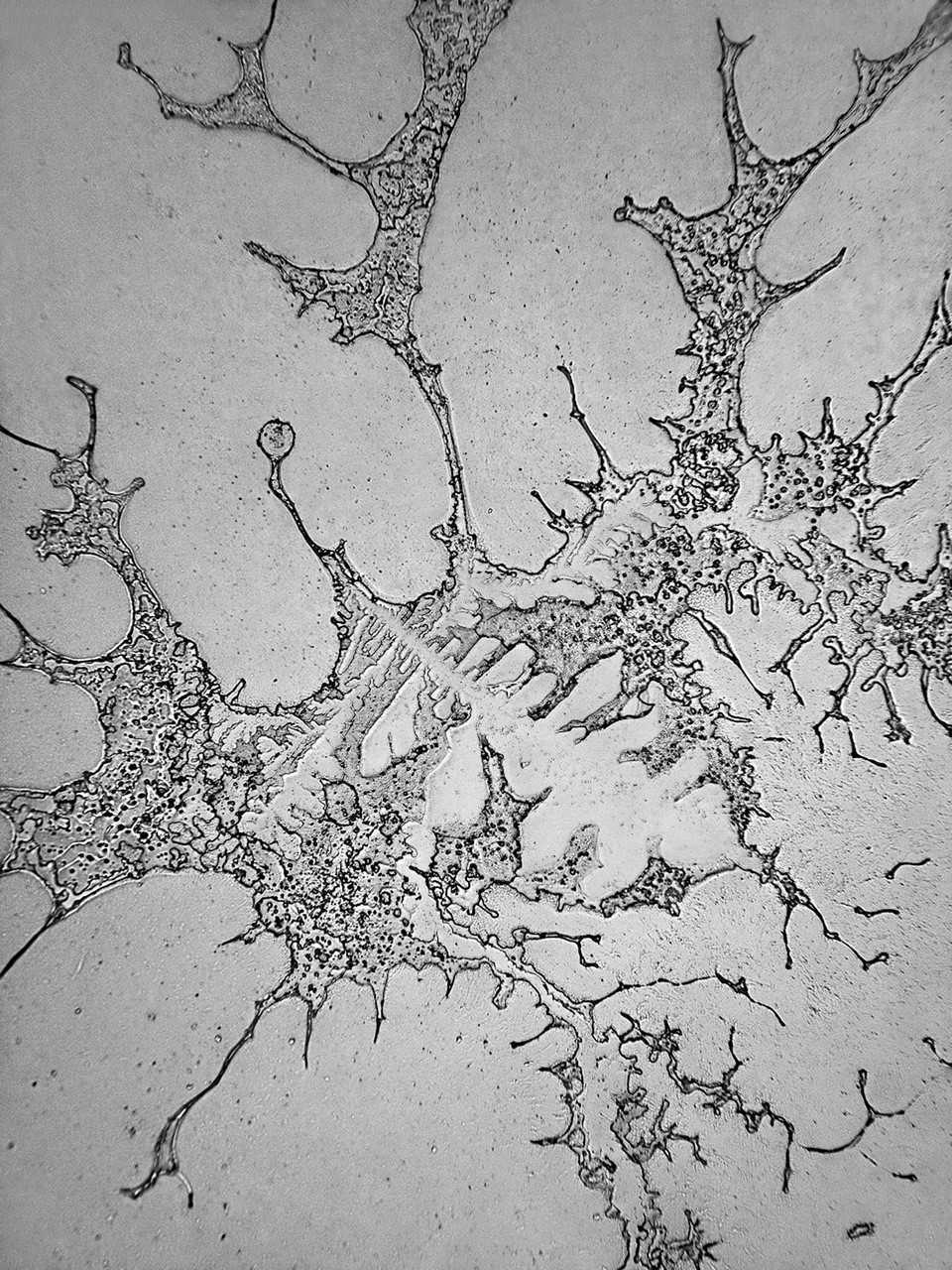

From ‘Water Pressure: Designing for the Future’ at MK&G, The Topography Of Tears, by Rose Lynn Fisher

W*: What can we expect to see this year?

JW: It’s a little bit different this year, because the theme is ‘The Practice of Learning’. If you’re a designer today, everything's constantly changing – with fast moving issues like climate change, AI, material research – you have to keep learning to keep up. With this in mind, we gave our spaces to designers and collectives who have learning and knowledge-sharing embedded in their practice. So they're not really the traditional ‘object on a plinth’ exhibitions, they're either the result of workshops or they're holding workshops in the spaces or discussing ways of bringing learning to life. We’ve turned it around a bit and I think the programming and creating energising spaces for people to interact will be the interesting aspect.

From ‘Water Pressure: Designing for the Future’ at MK&G, Goldeimer & Werkhaus Trockentoilette, Premium Plus

W*: In recent years, the validity of design festivals has often been questioned. Do you think they still have relevance and value?

JW: I think the problem is there's just too many of them. They're wonderful places for people to come together and make stuff happen. But there is an increasing sameness and they're in danger of being overtaken by things that are more about marketing than design; perhaps they’re victims of their own success. They need to be much more distinctive to be relevant. London’s strength is creativity and a spirit of invention, and I’d recommend searching out emerging designers and more experimental projects.

Brompton Design District, The Practice of Learning, London Design Festival 2024, 14 - 22 September bromptondesigndistrict.com

‘Water Pressure – designing for the future’ is on show at MK&G Hamburg until 13 October 2024

Read more: ‘If kids grew up going to London Design Festival they would learn so much’: architect Shawn Adams

Ali Morris is a UK-based editor, writer and creative consultant specialising in design, interiors and architecture. In her 16 years as a design writer, Ali has travelled the world, crafting articles about creative projects, products, places and people for titles such as Dezeen, Wallpaper* and Kinfolk.

-

The rising style stars of 2026: Connor McKnight is creating a wardrobe of quiet beauty

The rising style stars of 2026: Connor McKnight is creating a wardrobe of quiet beautyAs part of the January 2026 Next Generation issue of Wallpaper*, we meet fashion’s next generation. Terming his aesthetic the ‘Black mundane’, Brooklyn-based designer Connor McKnight is elevating the everyday

-

Mexico's Office of Urban Resilience creates projects that cities can learn from

Mexico's Office of Urban Resilience creates projects that cities can learn fromAt Office of Urban Resilience, the team believes that ‘architecture should be more than designing objects. It can be a tool for generating knowledge’

-

‘I want to bring anxiety to the surface': Shannon Cartier Lucy on her unsettling works

‘I want to bring anxiety to the surface': Shannon Cartier Lucy on her unsettling worksIn an exhibition at Soft Opening, London, Shannon Cartier Lucy revisits childhood memories