In the aftermath of Japan’s Noto earthquake, what’s next for Ishikawa crafts?

Craftspeople from the Ishikawa craft district tell Wallpaper* how the 2024 Noto earthquake affected their community, and what lies ahead

Nature-inspired Kaga yuzen silk dyeing. Boldly-glazed Kutani porcelain. Fine layers of gold leaf. Hand-carved Buddhist statues. And the lustrous surface depth of Wajima-nuri lacquerware. For centuries, Ishikawa Prefecture, in western Japan, has thrived as a deeply respected treasure trove of some of the nation’s finest examples of traditional craftsmanship. The region, which scenically hugs the coastline of the Sea of Japan, is home to a rich landscape of generations-old manufacturing hubs specialising in a spectrum of artisan expressions, from ceramics and woodwork to textiles.

Now, however, Ishikawa is in the spotlight for a different reason: it was the region hit hardest by the 7.6-magnitude earthquake that shook Japan on New Year’s Day 2024. As the dust begins to settle on the devastation – a death toll topping 221, with 22 still missing, plus more than 20,000 still in evacuation centres – the imprint of the disaster on Japan’s precious craft heritage is sharply coming into focus.

While immediate priorities remain survival, rebuilding and recovery, scenes of the impact on Ishikawa’s crafts industry are increasingly visible – broken ceramics, collapsed workshops, damaged factories. Ishikawa’s hardest hit area was Noto Hanto, a wildly beautiful rural peninsula jutting into seas and home to Wajima city – one of Japan’s three most important hubs for lacquerware craftsmanship, in particular its unique Wajima-nuri.

The Noto earthquake's impact on Ishikawa’s craft traditions

Kohei Kirimoto (an eighth-generation lacquer artist from Kirimoto) documented the destruction of the Wajima Asaiichi Market

With a lacquerware heritage dating back more than five centuries, as many as 1,100 people among Wajima’s 20,000-strong population work in the Wajima-nuri industry, according to local government figures.

In the ashes of the disaster, the city is now grieving the loss of its cultural heartbeat: Asaiichi Market, a bustling historic hub of seafood, snacks and crafts dating back 1,000 years, which was destroyed by fires. Countless generations-old workshops were devastated, many specialising in Wajima-nuri, a unique and durable style of lacquerware that has more than 100 steps in the making process, such as mixing Noto’s urushi lacquer tree sap with locally fossilised plankton called jinoko.

Among those impacted is Wajima Kirimoto, a long-respected, family-run business dating back 200 years, famed for filtering its finely honed technical craftsmanship through a timeless design perspective. Eighth-generation artisan Kohei Kirimoto posted extensive images on Instagram highlighting the damage across Wajima, as he searched among the rubble of his family’s former home and workshop for his much-loved cats.

The Aizawa Wood Works showroom, as it opened in late 2023 (and now destroyed by the earthquake)

'Ishikawa is often compared to Kyoto as a place where crafts are flourishing,' explains Yuji Akimoto, a curator, writer and leading figure in Japan’s arts and modern crafts world. He is deeply familiar with the region, as director of Go for Kogei, a regional crafts, arts and design festival, and former director of 21st Century Museum of Modern Art in Kanazawa.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

'Ishikawa alone represents Japan in terms of both variety and quantity, with ten nationally designated traditional crafts, six prefecture-designated crafts, and 20 rare traditional crafts. There are many craft production centres in Japan, but no other place produces such a wide variety and quantity.'

He adds: 'It will take time to recover from the devastation. Among the lacquer craft artists and artisans I know, there are many whose houses have collapsed or been half-destroyed, and some of them have not yet been able to confirm their safety. The collapse of a town means not only the loss of hardware such as buildings, but also the loss of livelihood and its foundation, which will take time to recover.

'Some craftspeople have come to Kanazawa and are preparing to resume their work there, while others are working in the disaster-stricken Wajima area, collecting tools from collapsed houses. There is also a movement to raise funds to support Wajima lacquerware, mainly by lacquer craftsmen. When I hear such stories, I feel the resilience of the people, which in turn gives me courage.'

Aizawa Wood Works showroom as it currently stands

Revitalising the craftsmanship eco-system that often underpins Japan’s making culture – with a thread of specialist artisans typically creating different components of a single product – is a key challenge. This is currently a focal point for Masanori Oji, a leading Japanese product designer, renowned for the quiet balance of contemporary design and modern craftsmanship in his objects for daily living, brought to life by specialist artisans.

Oji, who has visited Wajima monthly from his home in Kawagoe, north of Tokyo, for over a decade, is branding director and product designer for Aizawa Wood Works, a local woodworking manufacturer, which traditionally provides wooden bases for lacquerware craftsmen. 'The Kawaimachi area, a famous production site for Wajima lacquerware with many artisans, has been engulfed in fire, resulting in many craftsmen losing their homes, and there have been numerous casualties,' Oji tells Wallpaper*.

'Given the advanced age of many artisans, rebuilding both their homes and workshops seems impossible. Wajima lacquerware has been facing a decline in recent years, with a significant reduction in production. With these recent events, I feel that the tradition of Wajima lacquerware as a medium-scale production may be interrupted.

'This means that even if someone wishes to experience using Wajima lacquerware bowls, obtaining them immediately may become challenging. However, Wajima still boasts globally renowned lacquer artists and artists who continue their work.'

A series of wooden pieces by Aizawa Wood Works, inspired by an image of the sun setting over Noto

While Aizawa’s factory is still standing, it was widely damaged and it is uncertain whether it can be repaired. Yet through the grief and devastation, a mix of strength and innovation appears to be fuelling creative communities as they unite to forge a new path into the future.

'Without the wooden base, making lacquer products is not possible,' says Oji. 'Currently, Aizawa and I, along with the people of Wajima, are exploring the possibility of creating a new workplace for the displaced artisans. This is also seen as an opportunity to revitalise the lacquer industry, which had become outdated and dysfunctional. I find this endeavour both challenging and rewarding.'

He adds: 'Wajima, with its mountains, sea and craftsmanship is a captivating place. I will continue to share updates on social media to keep people aware of Wajima, as remembering this place is the best form of support. I hope to make efforts towards recovery and eventually invite everyone to enjoy Wajima.'

Lacquer work by Katsuji Kamata on show at Kyoto's Nunuka life

Among Noto lacquerware artisans affected by the disaster was Katsuji Kamata. His workshop – in Monzen, around 30km south of Wajima – was badly shaken but still standing after the earthquake, although many items were broken.

Last weekend, a pre-scheduled exhibition at Nunuka Life in Kyoto went ahead – in a stroke of luck, many works were already safely packed up at the time of the earthquake. The gallery, spanning an atmospheric two-level wooden house, showcases the fusion of his traditional craftsmanship and modern forms, with surfaces layered in deep shades of red and black. Kamata – who was jogging with his child at the time of the earthquake and was unable to stand due to the force of the tremors – highlighted his gratitude for the support and unity of the local creative community.

'Before, I worked quite independently,' he tells Wallpaper*. 'But after the earthquake, a lot of people helped me, many different craftsmen. It made me realise that I am part of the local collective and it is really important to represent that.'

For Shuya Takahashi, co-founder of Nunuka Life, going ahead with the exhibition was a way of expressing committed support to the region’s recovery. 'This is the only thing we can do at the moment. But when things become safer in the region, we would love to go and help more directly.'

Urushi, rice and cotton bowls by Wajima Kirimoto

The Noto Peninsula is also firmly on Japan’s contemporary art map, due to the Oku-Notu Triennale. The art festival was most recently held in autumn 2023 (after being postponed from May due to an earlier earthquake) with 34 new works by Japanese and international artists – including pieces by English sculptor Richard Deacon from his Infinity series.

The event unfolds across the remote landscape of Suzu, on the northern tip of Noto, which was severely damaged in the earthquake. Fram Kitagawa, festival founder and chairman of Tokyo`s Art Front Gallery, tells Wallpaper*: 'Roads and water supply continue to be cut off. There remain 26 artworks in place from the Oku-Noto Triennale throughout the year, but considering half of [local] houses are said to be completely or partially destroyed, they seem to be almost completely [lost].

'Upon learning of the news reports of the disaster, many artists have sent in offers of help and donations, and their hearts go out to the people in the affected areas. We are pleased to hear that artists are individually in contact with people they have a connection with, listening to them, and caring about them. We will keep posting on the status of the artworks and our policy of assistance from time to time.'

The aftermath of the Noto Peninsula earthquake with severe damage to the Aizawa Wood Works

The next step for the region, according to Akimoto, is to make a vision for a new future. Referring to the example of Wajima, he says: 'When we overcome the current phase, and move to the next step to think about a mid-long-term plan, we must ask ourselves what kind of future plan we should draw to restore Wajima's industry, culture, history and livelihood.

'In light of the historical background of Wajima, it is necessary to create some kind of a town planning concept where "people live together with crafts" that will lead to the next generation.'

How to help

Aizawa Wood Works

of Aizawa Wood Works

Danielle Demetriou is a British writer and editor who moved from London to Japan in 2007. She writes about design, architecture and culture (for newspapers, magazines and books) and lives in an old machiya townhouse in Kyoto.

Instagram - @danielleinjapan

-

ICON 4x4 goes EV, giving their classic Bronco-based restomod an electric twist

ICON 4x4 goes EV, giving their classic Bronco-based restomod an electric twistThe EV Bronco is ICON 4x4’s first foray into electrifying its range of bespoke vintage off-roaders and SUVs

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

‘Dressed to Impress’ captures the vivid world of everyday fashion in the 1950s and 1960s

‘Dressed to Impress’ captures the vivid world of everyday fashion in the 1950s and 1960sA new photography book from The Anonymous Project showcases its subjects when they’re dressed for best, posing for events and celebrations unknown

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

Inside Camperlab’s Harry Nuriev-designed Paris store, a dramatic exercise in contrast

Inside Camperlab’s Harry Nuriev-designed Paris store, a dramatic exercise in contrastThe Crosby Studios founder tells Wallpaper* the story behind his new store design for Mallorcan shoe brand Camperlab, which centres on an interplay between ‘crushed concrete’ and gleaming industrial design

By Jack Moss Published

-

Time, beauty, history – all are written into trees in Karimoku Research Center's debut Tokyo exhibition

Time, beauty, history – all are written into trees in Karimoku Research Center's debut Tokyo exhibitionThe layered world of forests – and their evolving relationship with humans – is excavated and reimagined in 'The Age of Wood', a Tokyo exhibition at Karimoku Research Center

By Danielle Demetriou Published

-

Minimal curves and skilled lines are the focal point of Kengo Kuma's Christmas trees

Minimal curves and skilled lines are the focal point of Kengo Kuma's Christmas treesKengo Kuma unveiled his two Christmas trees, each carefully designed to harmonise with their settings in two hotels he also designed: The Tokyo Edition, Toranomon and The Tokyo Edition, Ginza

By Danielle Demetriou Published

-

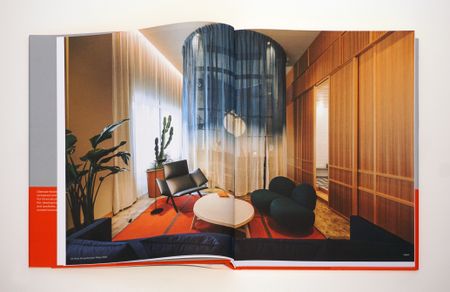

Claesson Koivisto Rune on 30 years of their often Japan-inspired designs, charted in a new book

Claesson Koivisto Rune on 30 years of their often Japan-inspired designs, charted in a new book‘Claesson Koivisto Rune: In Transit’ is a ‘round-the-world journey’ into the Swedish studio's projects. Here, the founders tell Wallpaper* about their fascination with Japan, and the concept of aimai

By Danielle Demetriou Published

-

Teruhiro Yanagihara's new textile for Kvadrat boasts a rhythmic design reimagining Japanese handsewing techniques

Teruhiro Yanagihara's new textile for Kvadrat boasts a rhythmic design reimagining Japanese handsewing techniques‘Ame’ designed by Teruhiro Yanagihara for Danish brand Kvadrat is its first ‘textile-to-textile’ product, made entirely of polyester recycled from fabric waste. The Japanese designer tells us more

By Danielle Demetriou Published

-

Craft x Tech elevates Japanese craftsmanship with progressive technology

Craft x Tech elevates Japanese craftsmanship with progressive technologyThe inaugural edition of Craft x Tech was presented in Tokyo this week, before making its first international stop at Design Miami Basel (11-16 June 2024)

By Danielle Demetriou Last updated

-

Ikea meets Japan in this new pattern-filled collection

Ikea meets Japan in this new pattern-filled collectionNew Ikea Sötrönn collection by Japanese artist Hiroko Takahashi brings Japan and Scandinavia together in a pattern-filled, joyful range for the home

By Rosa Bertoli Published

-

Junya Ishigami designs at Maniera Gallery are as ethereal as his architecture

Junya Ishigami designs at Maniera Gallery are as ethereal as his architectureJunya Ishigami presents new furniture at Maniera Gallery in Belgium (until 31 August 2024), following the series' launch during Milan Design Week

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

Nao Tamura's ‘Origata’ bench for Porro is inspired by kimonos

Nao Tamura's ‘Origata’ bench for Porro is inspired by kimonos‘Origata’ bench, by Nao Tamura, for Porro is among our Salone del Mobile 2024 highlights, featured in May Wallpaper*, on sale 11 April

By Léa Teuscher Published