Milan Design Week: Robert Wilson on the value of design in life

With a groundbreaking installation at Salone del Mobile 2025 and a new monograph, the celebrated director reflects on the role of furniture in his singular approach to theatre and design

'I’m 83 but have more work than ever,' Robert Wilson said this January while at The Watermill Center – the multivalent 'laboratory for the arts', foundation and home base he established on the East End of Long Island in the early 1990s. He was wrapping up his annual holiday – normally spent in Indonesia – and preparing for another prolific season of opera, exhibition and fashion show productions, among a slew of special projects. 'I’m first headed to Vilnius, Lithuania, where the National Opera and Ballet Theatre has commissioned me to develop a new work with a young composer,' he said.

Along the way, he also – most likely – made quick stops in Paris, Berlin, and Tokyo; cities that have fostered Wilson’s particularly avant-garde approach to theatre-making since the mid-1970s. He never stops travelling and is often found on a plane, hard at work sketching new ideas with a simple graphite pencil and printer paper. Perhaps most notable amongst the exhaustive raft of projects planned for 2025 are the especially 'operatic' installations and performances he’s conceiving for Salone del Mobile 2025 (8 to 13 April), the world’s pre-eminent furniture fair.

For his upcoming work, Mother, Wilson responds to and re-contextualises Michelangelo’s final, uncompleted work – the marble Rondanini Pietà (1564)

‘Mother’: Robert Wilson’s installation for Salone del Mobile 2025

What unifies everything for Wilson (or ‘Bob' as he prefers to be known), is light, a force that sometimes blends the chairs – and other designed objects – into their surroundings and at other intervals, makes them more conspicuous. 'So I can light this cup, turn all the lights out in the room, and continue talking,' he demonstrated while at The Watermill Center this January. 'The light will quickly become an active participant in the conversation.'

That same philosophy underpins Mother, an installation the revered director is developing for this year’s Salone del Mobile (see our Milan Design Week 2025 guide). Located in Milan's monumental Castello Sforzesco, it responds to and re-contextualises Michelangelo’s final, uncompleted work – the marble Rondanini Pietà (1564) – with a 30-minute sequence of multi-directional light and a score by inimitable Estonian composer Arvo Pärt.

As Wilson puts it: 'I’m creating my own vision of the artist’s unfinished masterpiece, torn between a feeling of reverential awe and profound admiration. Prevailing over all, however, is a feeling of serenity, of peace with oneself even in the face of the tragedy of death, which for me has nothing to do with religion. It is a universal image, a spiritual experience that moves something deep in us that needs no explanation.'

‘I’m creating my own vision of the artist’s unfinished masterpiece, torn between a feeling of reverential awe and profound admiration’

Robert Wilson

La Scala – the legendary Milan opera house that has hosted many of Wilson’s original productions and reinterpreted classics – will stage a one-night-only performance of The Night Before – Objects, Chairs, Opera / Milan. Inaugurating the 63rd edition of the furniture fair, the piece comprises five reimagined vignettes drawn from Wilson’s adaptations of La Traviata, Macbeth, Madame Butterfly, Norma and Othello. Each will feature key designed objects – not props – from the original productions. Michele Spotti will conduct the accompanying orchestra.

'Both will be very simple but powerful stagings,' Wilson notes. 'We'll do the La Scala performance once, which is compelling in its own sense. It’s like a shooting star.' Though performance is, by nature, inherently temporal, what remains for Wilson are his sketches, photographs, other ephemera and of course, the chairs.

Design as an implicit part of Wilson’s practice

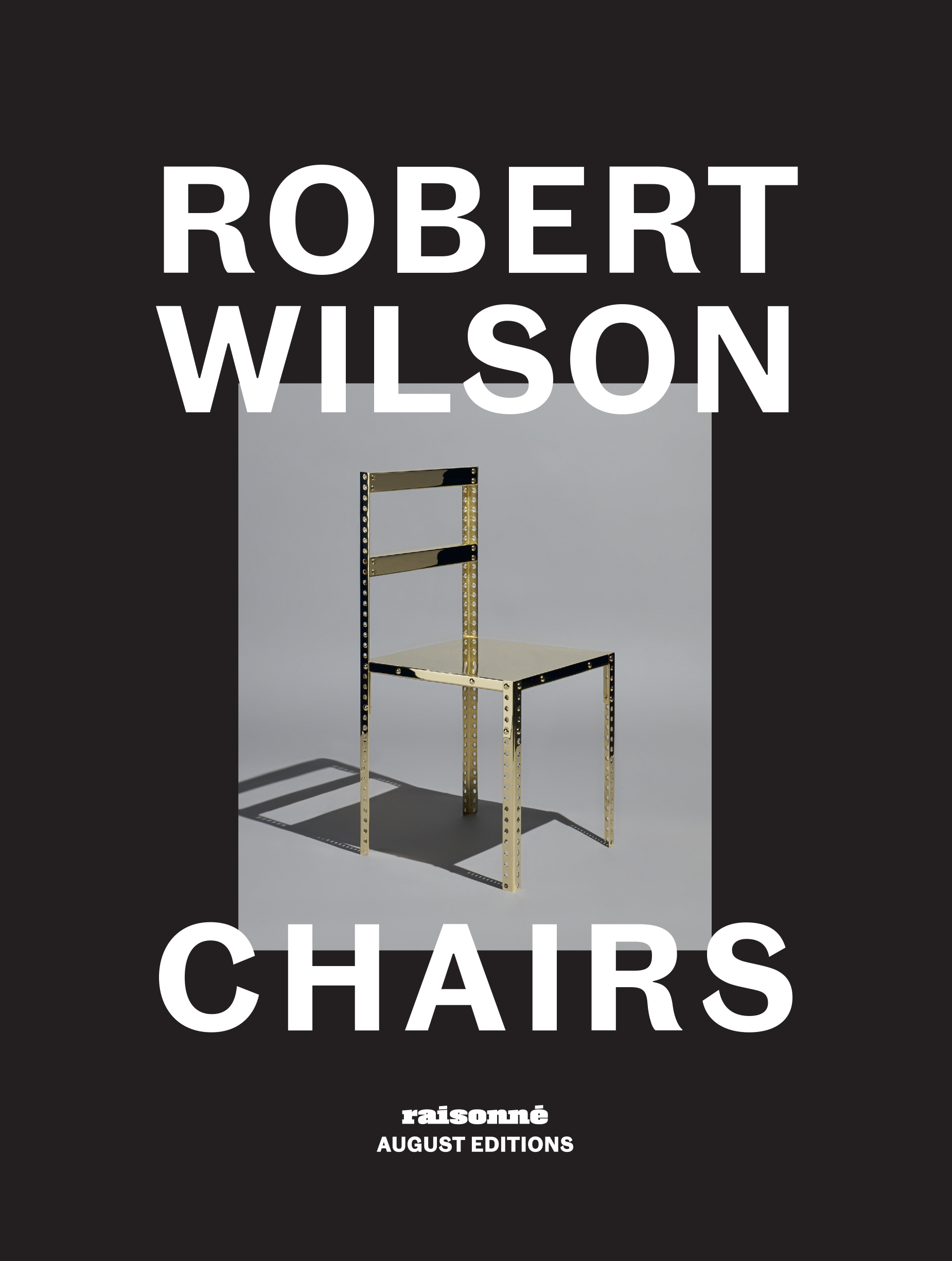

As a new book titled Robert Wilson: Chairs (to be published in July 2025) elucidates, design has been a fundamental facet of what he’s accomplished in the past 50 years. With early training in architecture, he has long treated his chairs and other furnishings not as secondary elements, but as compositional tools – helping to anchor and materialise the element of light – Wilson’s main instrument

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

These purpose-designed furnishings have also served to demarcate the passage of time, a convention Wilson has repeatedly pushed. Seminal early works like Einstein on the Beach – developed in 1976 with renowned composer Philip Glass – runs for over five hours. The KA MOUNTAIN AND GUARDenia TERRACE , his seven-day 'outdoor happening' at the 1972 Shiraz Festival in Iran, unfolded without pause. In one of his first plays, The Life and Times of Sigmund Freud (1969), a suspended metal mesh chair served as a 'main character', slowly descending from the proscenium over three acts, landing on the ground right on cue.

Beyond the opera house, Wilson has collaborated with various leading manufacturers and fashion houses on collectable design concepts and products (including for Wallpaper* Handmade in 2016) that have, increasingly, forayed into the realm of furniture. At the core of this exploration are his many chairs; concepts that are as much for stage and exhibition as they are for every life.

The ‘Queen Victoria Cafe Chair’, featured in Wilson's upcoming monograph

'They’re never props,' explains Wilson. 'They’re active participants in the production.' In his more than 12 stagings of Madame Butterfly – Italian composer Giacomo Puccini’s early 20th century masterpiece – the director has consistently deployed a 'waiting chair'. Evident behind a gauze scrim, the thin wooden settee greets the audience as they filter into the theatre. Much like Wilson himself, it quietly commands attention.

However pared back, these skillfully made, one-off pieces often carry the name and the essence of a production’s central figure: Pierre Curie, the Little Prince, Dr. Faustus. The ‘Marina Abramović Rocking Chair’, crafted in maple and birch, took centre stage in The Life and Death of Marina Abramović, Wilson’s 2011 biographical collaboration with the performance artist.

A new book surveying Wilson’s designs

‘A chair is not an arbitrary form,' writes art historian and long-time Wilson collaborator Owen Laub in his essay Drawing the Stage Around the Site, part of the Robert Wilson: Chairs monograph. 'A chair is a base architectural intervention providing the body with a complete set of instructions. The architecture of a chair can largely determine a body’s stature, posture, gesture, and by extension, power.'

The book, published by August Editions in partnership with New York gallery Raisonné, also features critical texts by Trevor Fairbrother and Glenn Adamson, and presents 45 of Wilson’s designs in chronological order, photographed by Dutch-American artist Martien Mulder, her ethereal lens evoking the style of Wilson’s otherworldly stagings. The book debuted in late February to coincide with a dedicated showcase at Raisonné, which also released 50 limited re-editions of the 1974 ‘Queen Victoria Café Chair’.

As Laub observes, the relationship between object and setting in Wilson’s work is never incidental: 'On stage, as sculpture performing the function of furniture, Wilson’s chairs complicate the relation between work and site. For Wilson, the form of a chair considers its position within the composition of a scene. In turn, the scene is composed to afford the chair a site.'

The dining room at The Watermill Center

While Wilson often imbues his designs with personal meaning, their role within the larger composition is just as crucial. The German composer Richard Wagner popularised the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk – a total work of art – and saw opera as its best manifestation – the ultimate coherence of all art forms – the fullest translation of life – be it literature through dramaturgy or the visual arts through elaborate backdrops.

‘Perhaps it took a theatre director to realise that a physical chair and its own insubstantial shadow could be given equal weight’

Glenn Adamson

'Perhaps it took a theatre director to realise that a physical chair and its own insubstantial shadow could be given equal weight,' writes Glenn Adamson writes in his essay, The Shadow of A Doubt, published in the book. 'Normally, in design, the object is all – an end in itself. In scenography, though, it is always part of a larger situation.'

The Watermill Center

Watermill: a total artwork in constant motion

Many of Wilson’s chairs and collected pieces are carefully placed throughout the four hectares (10 acres) of the Watermill Center – a space that in many ways serves as a more permanent and of course functional stage setting.

The ‘laboratory for the arts’ runs a year-round residency programme and an international summer programme, where Wilson works alongside students, collaborators and independent artists as they develop new work under his guidance.

The Watermill Center

The chairs – along with a broad array of works by Wilson’s peers – are in active use throughout the site, and for the most part, aren’t positioned behind vitrines as they might be in a museum. This approach reflects Wilson's belief that life is art, and art is life. British sculptor Henry Moore once said, 'there's no retirement for an artist, it's your way of living so there's no end to it' – an ethos Wilson follows emphatically. His legacy in many respects, Watermill, as much as any opera, exhibition, or fashion show, is the perfect manifestation of a total work of art – from its carefully planted gardens to the meals served three times a day.

Wilson is always willing to take visitors around the Watermill himself, offering up humorous anecdotes about how a specific design or artwork made its way to the centre. Many pieces are sparsely arranged in the main double-height rehearsal room – once a Western Union research facility, now transformed to reflect the pared-back aesthetic of the postindustrial downtown Manhattan lofts where Wilson lived and worked for much of the late 20th century.

Wood and stone objects displayed at The Watermill Center

Here, there are Frank Lloyd Wright windows, Frank Gehry armchairs, and various works featured in the Robert Wilson: Chairs monograph. A portrait of Andy Warhol in drag sits alongside salvaged items found on the streets of New York. All are displayed with equal aplomb. A near-unfunctional Philippe Starck stool flanks a far more rational Shaker bench. In one space, a methodically assembled Donald Judd desk plays nicely with a rose-embedded lucite armchair by Japanese powerhouse and Memphis Milano member Shiro Kuramata. A portrait Italian multi-hyphenate Gio Ponti drew of his daughter a few decades before hangs on the wall.

In the basement, a massive archive unfolds with illustrious items such as Marlene Dietrich’s diamond-studded pumps, a superhero mask picked up at a market in Jakarta, prehistoric wooden totems, and the ‘Freud’ lounger – a critical protagonist in the 1969 production The Life and Times of Sigmund Freud, also featured prominently in the monograph. 'The room we’re sitting in is a library with the Western Union archive and my own, as well as that of the local indigenous Shinnecock Nation that goes back 13,000 years,' Wilson concluded while at The Watermill Center earlier this year, looking ahead to another busy year ahead.

Robert Wilson's Mother will be on show in Milan during Salone del Mobile 2025 and until 18 May, salonemilano.it/en

Check our guide to Milan Design Week 2025 for more must-sees

Adrian Madlener is a Brussels-born, New York-based writer, curator, consultant, and artist. Over the past ten years, he’s held editorial positions at The Architect’s Newspaper, TLmag, and Frame magazine, while also contributing to publications such as Architectural Digest, Artnet News, Cultured, Domus, Dwell, Hypebeast, Galerie, and Metropolis. In 2023, He helped write the Vincenzo De Cotiis: Interiors monograph. With degrees from the Design Academy Eindhoven and Parsons School of Design, Adrian is particularly focused on topics that exemplify the best in craft-led experimentation and sustainability.

-

Tokyo design studio We+ transforms microalgae into colours

Tokyo design studio We+ transforms microalgae into coloursCould microalgae be the sustainable pigment of the future? A Japanese research project investigates

By Danielle Demetriou

-

What to see at London Craft Week 2025

What to see at London Craft Week 2025With London Craft Week just around the corner, Wallpaper* rounds up the must-see moments from this year’s programme

By Francesca Perry

-

The Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Perpetual Calendar watch solves an age-old watchmaking problem

The Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Perpetual Calendar watch solves an age-old watchmaking problemThis new watch may be highly technical, but it is refreshingly usable

By James Gurney