Rubik’s Cube inventor on 50 years of the cult puzzle

As the Rubik’s Cube turns 50, Wallpaper* talks to its inventor, Ernő Rubik, about the ingenious design’s history

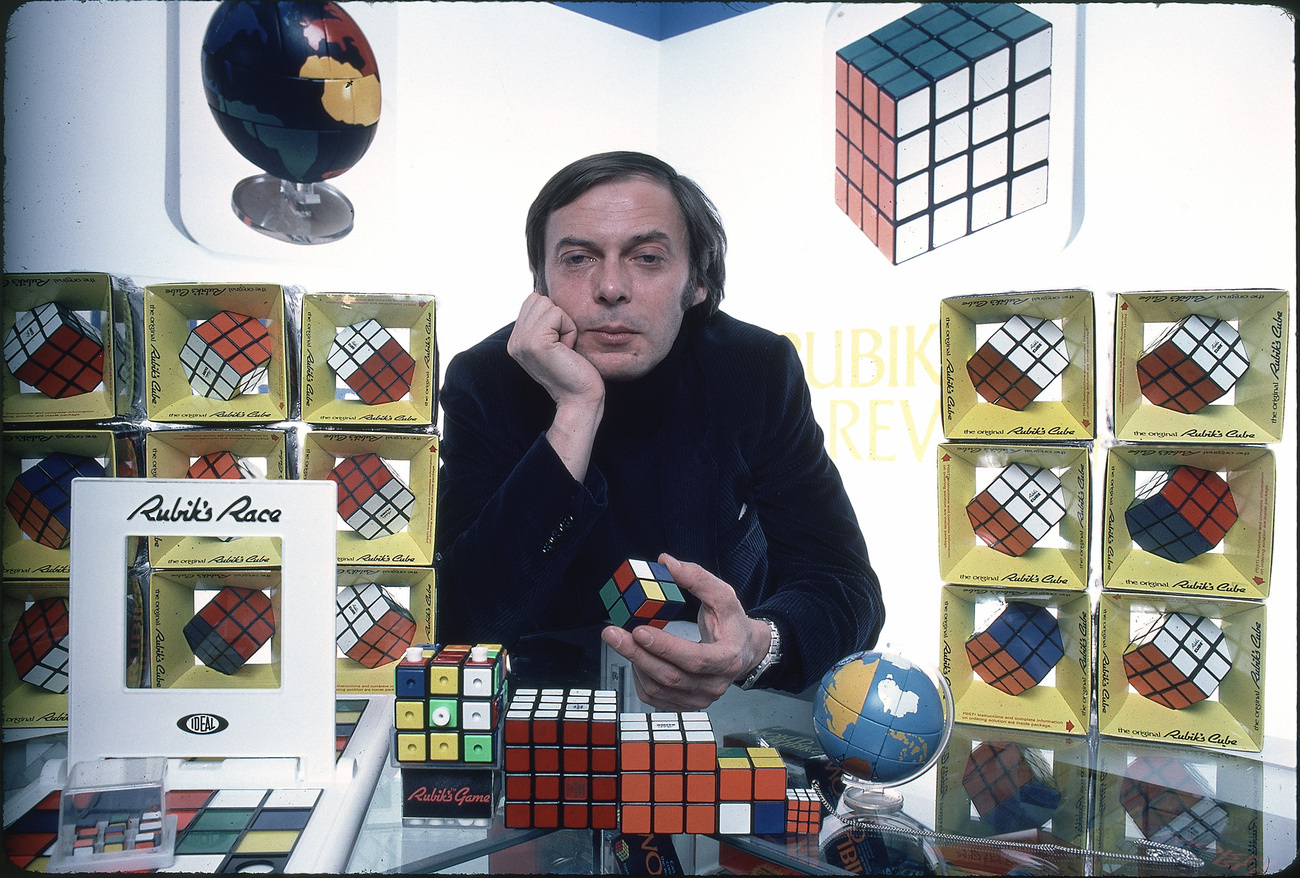

Hidden away in Budapest’s Buda Hills stands Hungarian inventor Ernő Rubik’s minimalist five-storey abode. Adorned with multiple scenic terraces, it stars an elevator that conveniently glides between levels and furniture of Rubik’s own design. 'Yes, I made other things, too,' he tells Wallpaper* on a tour through the home’s comfortable rooms, 'but people only want to talk about the cube.'

The cube, of course, is the compact Rubik’s Cube, the bestselling 3D combination puzzle (a tasteful amount of memorabilia is strewn about the house) originally known as the Magic Cube, that Rubik serendipitously dreamed up back in 1974. Twisting and turning into some 43 quintillion permutations, the six-sided cube is clad in vibrantly tinted squares that beckon enthusiastic problem solvers.

Rubik’s Cube turns 50

For five decades now – coinciding with Rubik’s 80th birthday in July – the cube has endured as a design marvel, a seemingly simple yet challenging lightweight plastic toy that vexes the impatient. 'Fifty years means that you’ve arrived, that you’ve done something,' explains Rubik. 'The cube has lived so long, and, in my view, it still seems alive and full of energy for the next generations, so it’s an interesting thing. All I wanted to do was put something together and share it with people.'

Indeed, Rubik never anticipated that his invention would become a timeless, global sensation, spawning speedcubing competitions and ample knock-off versions. The Rubik Cube has sold more than 500 million units since its launch, is part of The Museum of Modern Art in New York’s permanent collection, and is entrenched in pop culture.

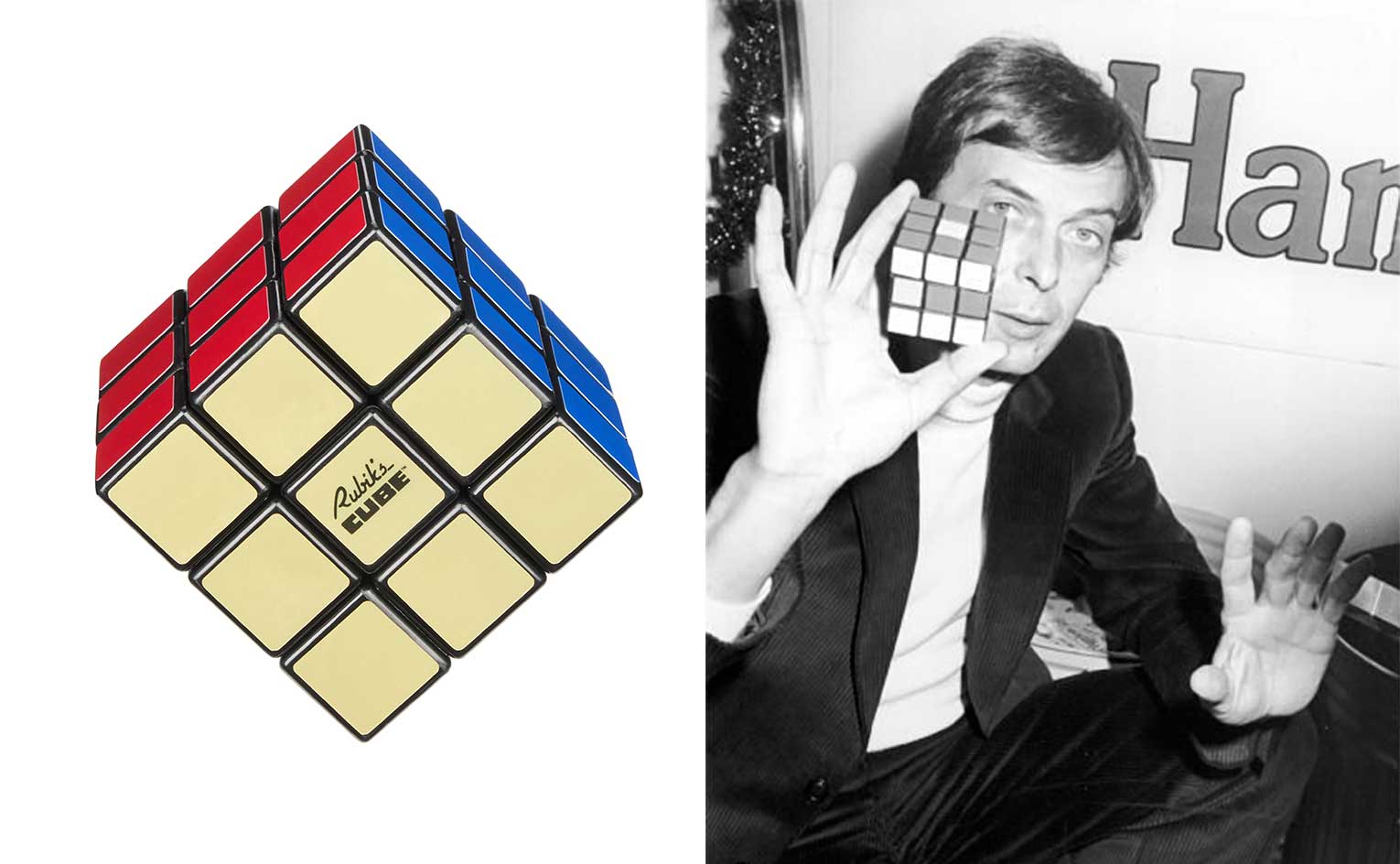

A 1980s Rubik’s Cube

'Most things in life and in nature happen accidentally,' Rubik points out, and the cube was also born by happenstance. After first exploring sculpture, Rubik, undoubtedly inspired by his aviation engineer father, studied architecture, and eventually taught it at the University of Applied Arts in Budapest, now the prestigious Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design (MOME). 'I made some architecture work but never worked as an architect. I loved the workshops,' he says.

In his 2020 book Cubed: The Puzzle of Us All, equal parts memoir and philosophical insights, Rubik describes the room in which he prepared for his classes as 'a child’s pocket, full of marbles and treasures', including 'innumerable cubes: cubes made of paper, of wood, monochrome or coloured, solid or broken down into blocks'.

The invention of the Rubik’s Cube

The original Rubik’s Cube

Holed up in this wondrous den at the university, he hatched what would become the Rubik’s Cube. Keen to strengthen his students’ understanding of spatial relationships, he built various, evolving models. For example, he drilled holes into identical cubes of wood and connected them with rubber bands, later fishing lines, in the hopes of creating self-contained structures that also possessed the freedom of independent movement.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

When they all fell apart, Rubik persevered, ultimately finding the solution in the form of a well-concealed mechanism. It successfully held together the cube, updated in plastic and now defined by distinct hues on each of its faces – yellow, blue, red, green, orange, and white. 'Design is a complex thing. It’s science, it’s art, it’s technology,' muses Rubik. 'Sitting on the table the cube is gorgeous. It has so much potential.'

An early prototype

Rubik’s initial prototypes were unpolished but served as dynamic geometry lessons that his students and colleagues appreciated. Not long after, he submitted his patent application for the Magic Cube. ‘Once the process started, it had a surprising effect. When you are in the middle, you can’t really see what’s happening. After a while, you look back and see it was wonderful,’ he remembers.

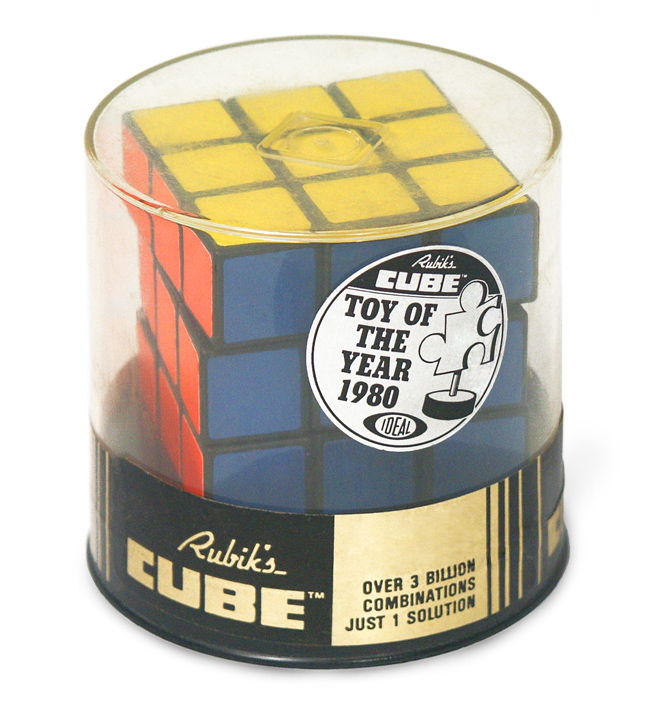

Rubik introduced the cube during the dark days of Communism in Eastern Europe, and although the addictive puzzle was a hit in Hungary, it was hard to gain wider exposure from behind the Iron Curtain. The cube’s fate changed in 1979, when it made a splash at the Nuremberg International Toy Fair. Momentum continued when Ideal Toy Company in the US began to distribute what it had renamed the Rubik’s Cube in 1980.

Ernő Rubik

Now part of the Spin Master portfolio, Rubik’s Cube is celebrating 50 years with a retro anniversary edition flaunting sharp edges and stickers that transports users back to the 1970s, during the heady days of the cube’s rise to unexpected cultural icon.

'I always loved science fiction and the greatness and capability of the human mind to create good, beautiful things. I was curious, but I had no money from work, partly because of the circumstances and partly because I was not looking for it,' Rubik recalls. 'If you are lucky like me, you do what you want to do and don’t mind if you can sell it.'

The Rubik Cube special retro anniversary edition is available from Amazon

Alia Akkam is a native New Yorker living in Budapest. She writes about interiors, hotels, travel, food, culture and drinks. She is also an Academy Chair for World’s 50 Best Bars.

-

How Charles and Ray Eames combined problem solving with humour and playfulness to create some of the most enduring furniture designs of modern times

How Charles and Ray Eames combined problem solving with humour and playfulness to create some of the most enduring furniture designs of modern timesEverything you need to know about Charles and Ray Eames, the American design giants who revolutionised the concept of design for everyday life with humour and integrity

-

Why are the most memorable watch designers increasingly from outside the industry?

Why are the most memorable watch designers increasingly from outside the industry?Many of the most striking and influential watches of the 21st century have been designed by those outside of the industry’s mainstream. Is it only through the hiring of external designers that watch aesthetics really move on?

-

This Fukasawa house is a contemporary take on the traditional wooden architecture of Japan

This Fukasawa house is a contemporary take on the traditional wooden architecture of JapanDesigned by MIDW, a house nestled in the south-west Tokyo district features contrasting spaces united by the calming rhythm of structural timber beams