Explore 100 years of Svenskt Tenn and the interiors Estrid Ericson has crafted

‘A Philosophy of Home’ explores 100 years of Svenskt Tenn and the daring vision for interiors its founder Estrid Ericson developed

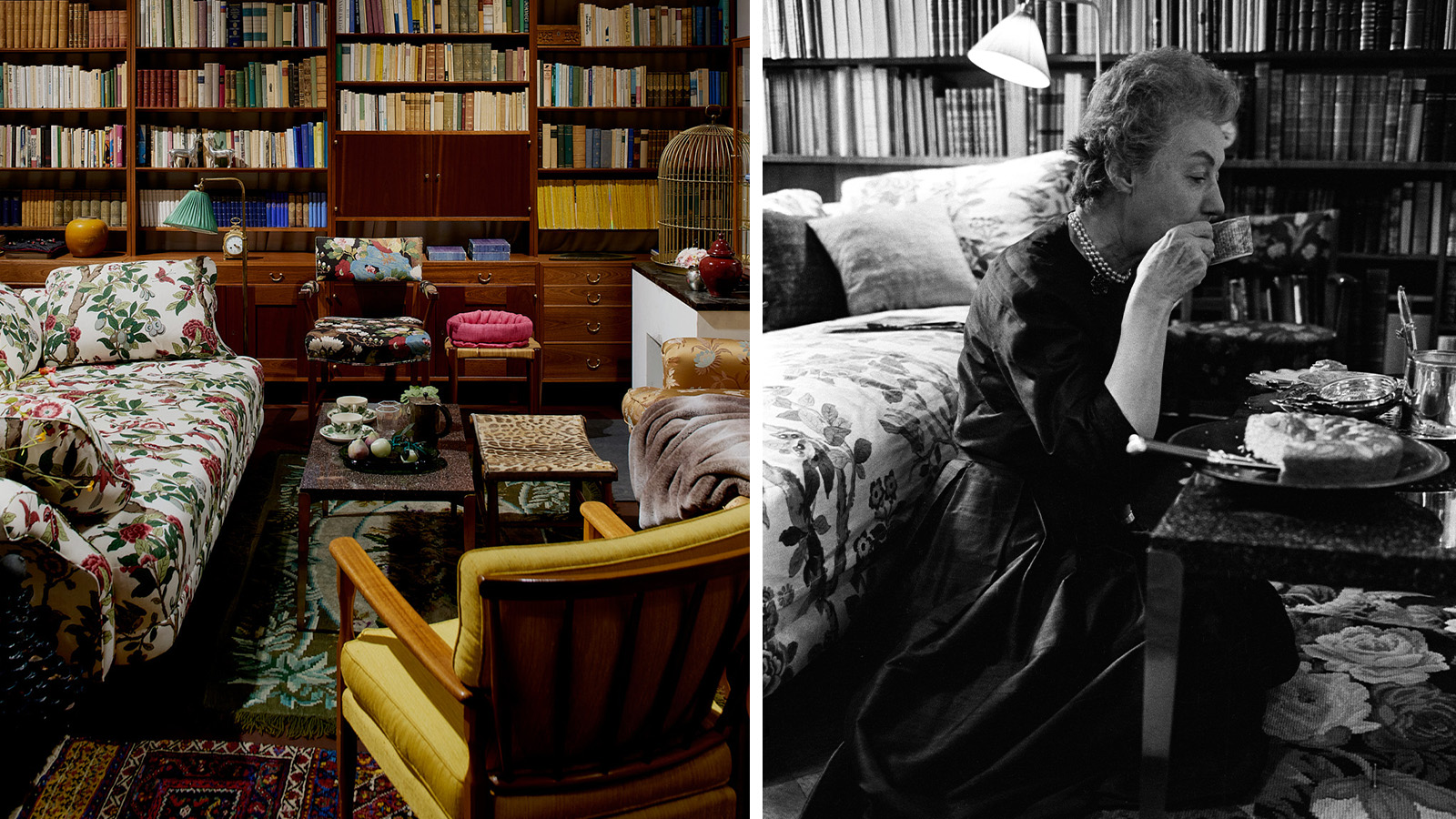

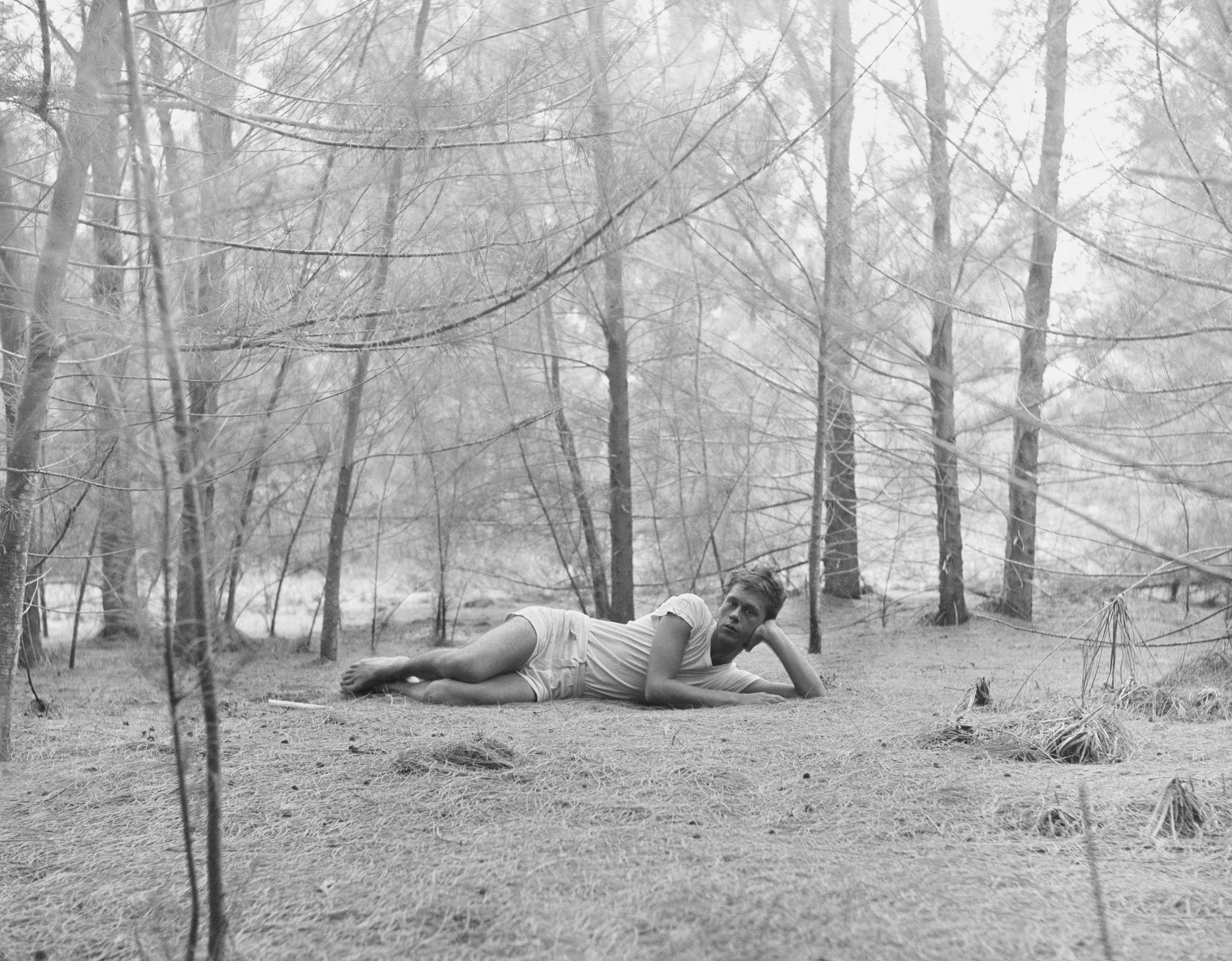

Estrid Ericson, the dynamic founder of the pewter workshop turned interiors brand Svenskt Tenn, lived a few floors above her shop on Stockholm’s famed Strandvägen, a majestic tree-lined waterfront esplanade. Her apartment was adorned with furniture her brand designed and sold, souvenirs from trips abroad, and objects she picked up at flea markets. It changed throughout the years, representing her belief that “our homes are never completed,” as she wrote in a 1939 essay. But an archival photo shows it during a particularly elegant, yet relaxed, moment: Ericson, wearing strands of pearls and a brocade dress, is lying under a fur blanket on a floral sofa while reading a book. Her dog is sprawled out at her feet and her cat sits on a zebra-print table just a few feet away. It’s a comforting, welcoming, and joyful space—the qualities that demonstrated her definition of Swedish modernism.

A remarkably faithful recreation of this living room is part of ‘Svenskt Tenn: A Philosophy of Home,’ an exhibition at Stockholm’s Liljevalchs museum that celebrates the company’s 100th anniversary this year. Organized by Karin Södergren, Svenskt Tenn’s head curator, and Jane Withers, an independent curator, the show unfolds in 13 thematic rooms featuring an extensive array of furniture, objects, and never-before-exhibited ephemera from the company’s vast archive. Many of the objects in the exhibition will be familiar to Svenskt Tenn fans—particularly the exuberant Josef Frank botanical textiles and glimmering pewter tableware—but what comes into focus in this retrospective is how enduring Ericson’s values are.

‘A Philosophy of Home’ explores 100 years of Svenskt Tenn

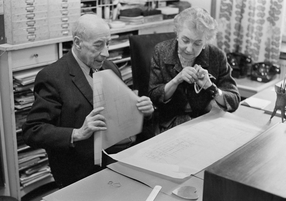

Estrid Ericson and Josef Frank in the shop_Swedish Tenn Archive and collections

While Ericson and Frank have had exhibitions of their own, ‘A Philosophy of Home’ is the first time that their narratives are brought together in context with the brand they built. 'It is immensely exciting,' says Svenskt Tenn CEO Maria Veerasamy about staging the exhibition. 'Witnessing everything come to life prompts a moment of reflection and pride, as we see a century’s worth of creativity and craftsmanship.'

It’s unusual for century-old furniture brands to exist today, let alone remain relevant and beloved in the design world; however, Svenskt Tenn managed not to be mothballed because of Ericson’s vision for her company. She championed artisanry, had an instinct for finding talented designers, and challenged societal norms about what a home should embody. But overall, she championed a generous definition of modernism that allowed for individual expression. With this exhibition, she is finally receiving the full recognition she’s due.

Estrid Ericson 1939. Photo from the Svenskt Tenn Archive

'She is obviously known in a Swedish and Nordic context, but she deserves to be a bigger figure in the world at large,' Withers says. “It's such a fascinating story to have this dynamic young woman who came from a comparatively small town, came to Stockholm, moved in very progressive circles, and created this extraordinary vision for how we might live.'

Born in 1894, Ericson was raised in Hjo, a small town about 330 kilometers southwest of Stockholm, where her family ran a popular hotel. It’s through this experience that she learned about hospitality and creating a feeling of home, which became a core part of Svenskt Tenn. She left home at 19 to study at what is now the Konstfack University of Arts, Craft and Design and was drawn to the writing of Ellen Key, a feminist social theorist; the work of Gregor Paulsson, a modernist industrial designer; and the interiors of Karin and Carl Larsson, who believed that homes could become platforms for social change. After graduation, she worked in a couple of interior design firms in Stockholm before opening Svenskt Tenn with her friend and business partner Nils Fougstedt, a sculptor and silversmith.

‘Svenskt Tenn: A Philosophy of Home’ is on view at Stockholm’s Liljevalchs Museum

For the first few years of her business, Ericson focused on producing pewter objects (Svenskt Tenn translates to “Swedish pewter). She collaborated with artists like Uno Åhrén and Björn Trägårdh and often incorporated references from artifacts she saw in Stockholm’s anthropology museums. In addition to stocking pewter products designed in house, Ericson sold home goods and objects that she found during international trips and at flea markets. 'This curiosity and love for diverse cultures deeply influenced the eclectic style of Svenskt Tenn,' Södergren says. 'She built the shop as a place of cultural exchange as well as retail.' Svenskt Tenn quickly became popular, especially among progressively minded women.

Ericson was a savvy entrepreneur and found ways to keep Svenskt Tenn in the press. She staged photo shoots in her apartment and invited customers upstairs so that they could see the many ways they might be able to style her furniture and home goods. Ever the host, she created elaborate table settings in her showroom and taught shoppers how to emulate them at home. (Keep candles high for flattering light, and floral arrangements low so as not to block conversation, she advised.)

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘Svenskt Tenn: A Philosophy of Home’ is on view at Stockholm’s Liljevalchs Museum

But overall, she lived the lifestyle she sold—an early version of today’s design influencer. 'She was able to play with her own image and use it as a foundation for Svenskt Tenn, ' Withers says. 'From very early on, she used her home as a set for the store to communicate ideas. It’s a vision that has become familiar. She could be a proto Conran.'

In the 1930s, Ericson began what would become a decades-long collaboration with Frank, who fled to Sweden from Austria seeking a haven from the rise of anti-Semitism and fascism. In Vienna, Frank ran the design firm and shop Haus & Garten and encouraged his clients to mix patterns, choose furniture that was comfortable, and embrace eclecticism. He brought this approach with him to Svenskt Tenn, which impacted Ericson’s perspective. The two worked together until he died in 1967.

Estrid Ericson and Josef Frank Photo Lennart Nilsson 1964

'When Ericson founded Svenskt Tenn in 1924, she aligned herself with the prevailing movements of modernism and functionalism,' Veerasamy explains. 'However, she gradually began to challenge these ideals, a shift that gained momentum with the arrival of Frank. Together, they developed an interior philosophy that defied the established Swedish style, promoting a humanistic view of the home as a place for genuine living and freedom—an approach that stood in stark contrast to the more restrictive design ideals of the time.'

The social context undoubtedly influenced this shift and the lifestyle Svenskt Tenn embodied became an example of the broader values that Ericson and Frank wished to see in the world at large.

'The thirties were difficult for political reasons, a scary time, not unlike our own time, and they invented the home as a haven amongst other things as a place of individual freedom, but a place you could live freely,' Withers says. 'It’s about physical and psychological comfort. The home is a kind of background, a framework. It's not about a perfect image or anything, but it's really about somewhere that puts people at ease to enjoy company or enjoy being.'

‘Svenskt Tenn: A Philosophy of Home’ is on view at Stockholm’s Liljevalchs Museum

To that end, Svenskt Tenn represented a certain kind of stylistic omnivorousness. It sold elaborately woven rattan chairs, pewter accessories moulded into playful animal motifs, fabrics printed with exuberant botanical patterns, tables with minimalist silhouettes made from expressive woods, and much more—all of which is on view at Liljevalchs. What was most important to its sensibility was the mixture of things in a home that would evolve right along with the person who lived there.

In 1958, Frank penned an essay titled “Accidentism” which described the design philosophy he and Ericson channelled through Svenskt Tenn. 'A living room in which one can live and think freely is neither beautiful nor harmonic nor photogenic,' he writes. 'It is the product of coincidences.'

As the architecture historian and Frank scholar Christopher Long explains, the essay reminds us of the value of diversity in design and experimenting outside the rules—something that feels particularly relevant today as stylistic sameness metastasizes around the globe (and in our algorithms) and rapid-fire trend cycles encourage indiscriminate consumerism.

‘Svenskt Tenn: A Philosophy of Home’ is on view at Stockholm’s Liljevalchs Museum

'It's so refreshing to come across such a generous way of thinking about how people should live that's so open to the mess of lives and playfulness and sort of delight,' Withers says. 'And I think for me, that's why it's so relevant today.'

Ericson wanted her company to outlive her. Before she retired, Ericson sold Svenskt Tenn to a non-profit foundation, which has a directive to promote social good. Today, this includes funding research on environmental issues and, of course, promoting Swedish craftsmanship, design, and architecture. It’s a framework that enables the brand to meet the moment while staying true to her legacy. To wit: the company continues to work with its longstanding stable of family-owned fabricators and producers while bringing in contemporary designers like Michael Anastassiades, Carina Seth Andersson, and India Mahdavi to develop new products. 'Ericson’s approach has taught me that integrity does not necessitate standing still; rather, it allows one to move forward in one’s own way and at one’s own pace,' Veerasamy says.

Interestingly, it’s a vision that is applicable to anyone, not just Svenskt Tenn shoppers (although in Sweden, you’d be hard pressed to find someone who hasn’t lived with something from them). Södergren hopes that the exhibition shows visitors to Liljevalchs how they might be able to apply Ericson and Frank’s philosophy to their own homes. “It’s much more than a list of ‘rules’ but rather a philosophy that can inspire us how to live,” she says.

‘Svenskt Tenn: A Philosophy of Home’ is on view at Stockholm’s Liljevalchs Museum through 12 January 2025. liljevalchs.se

Diana Budds is an independent design journalist based in New York

-

Aesthetics and acoustics come together in the Braque speakers from Nocs Design

Aesthetics and acoustics come together in the Braque speakers from Nocs DesignThe Braque speakers bring the art of noise, sitting atop a brushed steel cube that wouldn’t look out of place in a contemporary gallery

-

Inside the seductive and mischievous relationship between Paul Thek and Peter Hujar

Inside the seductive and mischievous relationship between Paul Thek and Peter HujarUntil now, little has been known about the deep friendship between artist Thek and photographer Hujar, something set to change with the release of their previously unpublished letters and photographs

-

In addition to brutalist buildings, Alison Smithson designed some of the most creative Christmas cards we've seen

In addition to brutalist buildings, Alison Smithson designed some of the most creative Christmas cards we've seenThe architect’s collection of season’s greetings is on show at the Roca London Gallery, just in time for the holidays

-

Svenskt Tenn Jubilee pattern by Josef Frank shows Stockholm’s popular streets

Svenskt Tenn Jubilee pattern by Josef Frank shows Stockholm’s popular streetsSvenskt Tenn releases a 1949 print by Josef Frank featuring a stylised map of Stockholm to mark the Swedish brand's centenary

-

Svenskt Tenn brings back rare furniture designs to mark its centenary

Svenskt Tenn brings back rare furniture designs to mark its centenarySvenskt Tenn kicks off its centenary celebrations with two rare pieces from the archives by Josef Frank and Nils Fougstedt

-

Svenskt Tenn gets a summer makeover courtesy of Margherita Missoni

Svenskt Tenn gets a summer makeover courtesy of Margherita MissoniAt Svenskt Tenn, Margherita Missoni curates 'A postcard from Italy,' a summer takeover of the Stockholm gallery (until 27 August 2023), as well as special edition pieces

-

Svenskt Tenn: The American Chapter celebrates Josef Frank's travels and legacy

Svenskt Tenn: The American Chapter celebrates Josef Frank's travels and legacyA new journal by Svenskt Tenn celebrates Josef Frank's travels around the United States

-

‘Pleated for Frank’ at Svenskt Tenn pays homage to a beloved 20th-century designer

‘Pleated for Frank’ at Svenskt Tenn pays homage to a beloved 20th-century designerFolkform and Svenskt Tenn present a homage to the classic plissé lampshades by Josef Frank (until 19 May 2023)

-

India Mahdavi interprets Josef Frank’s legacy at Svenskt Tenn

India Mahdavi interprets Josef Frank’s legacy at Svenskt TennStockholm Design Week 2022: India Mahdavi and Svenskt Tenn present ‘Frankly Yours’ (until 23 October 2022), an exhibition juxtaposing the company’s iconic prints with Mahdavi’s visual language