Designers and artists bring 3D printing into sharp relief at the Centre Pompidou

The printed world isn’t flat. That’s the main takeaway of ‘Imprimer Le Monde’ (‘Print the World’), a mind-bending exhibition at the Centre Pompidou, where a striking selection of 3D-printed objects reflects the diverse and ambitious visions of designers, artists and architects. It’s the type of show that presents myriad entry points for visitors depending on their existing knowledge of the disruptive technology.

Some may find themselves drawn to the overall unfamiliar aspect of otherwise familiar forms (Laureline Galliot’s teapot; Studio Swine’s ‘Meteorite’ platform shoes in aluminium foam); others might be determined to understand the actual concept of additive manufacturing – how machines are programmed to construct something layer by layer based on complex algorithms and computer-assisted design.

Certain examples maintain a connection to artisanal workmanship (the Bouroullec brothers integrate 3D-printed nodes into a geometric chestnut wood screen); while Daniel Widrig’s life-size man and woman standing in some sort of suspended liquefied state are meant to represent notions of transhumanism and artificial intelligence, hence their name, The Descendants. The fact that nearly everything presented has been realised within the last five years attests to the incredible speed at which individuals and companies are turning pioneering ideas into tangible prototypes.

Whether the ridged and pleated ceramic vases by Olivier Van Herpt that appear as if in fine linen, Mathias Bengtsson’s ‘Growth Table’ with its twisting legs newly manufactured in titanium, or Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s mask-like faces composed from genetic material collected in public places, the works suggest the enormous potential of digital technology to transcend typical notions of craftsmanship and beauty. Michael Hansmeyer and Benjamin Dillenburger’s ‘Grotto II’ presents a ‘digital grotesque’ that is epic as far as execution; the 260 million facets have materialised from silica sands and a binding agent into a fossilised alien artwork – or else some type of baroque cave infested with ghostly overgrowth.

3D-printed resin typography block, by Richard Ardagh.

At the other end of the spectrum is the 3D-printed resin typography block conceived by Richard Ardagh from New North Press conceived in collaboration with A2-Type and Chalk Studios. As a means of preserving traditional art of letterpress – of printing on a flat page – it ingeniously flips the paradigm; and to wit, the balloon-like letters on display read ‘Imprimer’.

Overseen by chief curator Marie-Ange Brayer and associate curator Olivier Zeitoun, the show does a fine job of alternating the focus between process and product. A delicate, constellation-like canopy developed by the University of Tokyo Advanced Studies Research Unit (with the participation of Kengo Kuma) can be appreciated in and of itself, for instance; but even more so after watching the screen that shows how it was created.

A timeline near the show’s entrance provides the antecedents and inventions that laid the groundwork for the technology as it exists today. One hundred and fifty years before 3D-printed cells and chairs, there was a ‘photosculpture’ from 1860 by François Willèm, who used a photo plus a pantograph (an instrument that copies a drawing at a different scale) to depict his male subject.

Fast forward 150 wildly innovative years and various iterations maintain some semblance to the human form – see Jon Rafman’s cratered sea foam bust, or Neri Oxman’s transparent, otherworldly masks impregnated with veiny fibres – only manipulated as though a biology experiment. Meanwhile, abstract acoustics from an installation by Ircam exploring the reproduction of 3D sound permeate the space; they underscore, quite literally, the strange and surprising artistic output emerging in this new age of machines.

Adjacent to the exhibition is a retrospective on Ross Lovegrove, which lays out his vast body of work, from the mass consumption ‘Ty Nant’ water bottle to the conceptual, self-sufficient Swarovski Generator House. Both shows mark the debut of ‘Mutations/Créations’, an annual event hosted by the Centre Pompidou as a platform for envisioning the future of art and interdisciplinary design.

From left, concrete columns, by Gramzio Kohler Research; ‘Grotto II’, by Michael Hansmeyer and Benjamin Dillenburger; and ‘Où sont nos souvenirs rangés’, by Vincent Fournier.

Left, Daniel Widrig’s life-size man and woman; ridged and pleated ceramic vases by Olivier Van Herpt (centre).

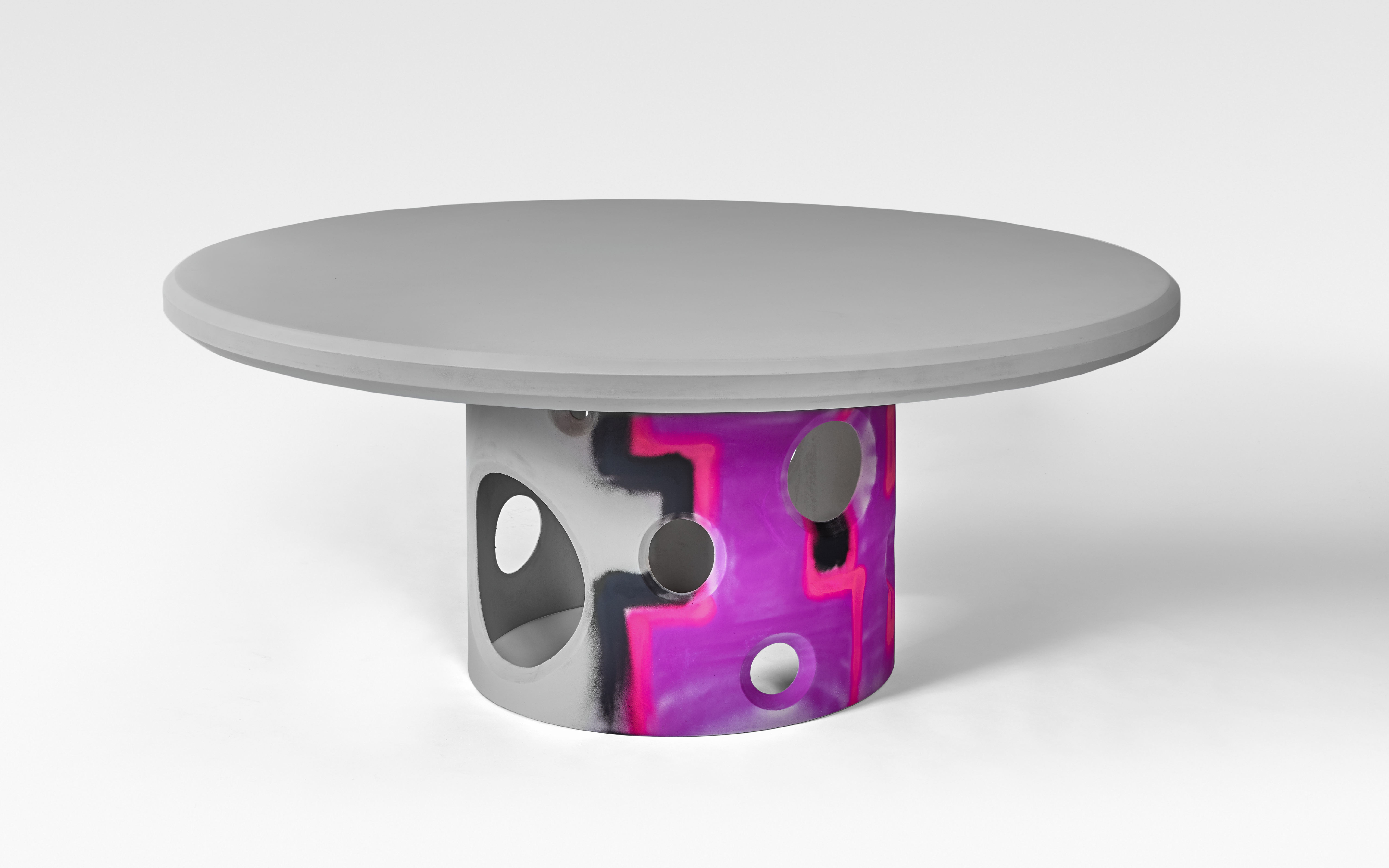

The show does a fine job of alternating the focus between process and product. Pictured, works by Mathias Bengtsson, Nendo and Joris Laarman.

From left, ‘Voxel’ chair, by Bartlett researchers; ‘Shapes of Sweden’, by Lilian Van Daal; one of the earliest pieces in the show, ‘Chaise Fab #71’, by François Brument and Ammar Eloueini; ‘Transitional Fields’, by Studio Aleksa; and ‘Endless Chair’, by Dirk Vander Kooij.

INFORMATION

‘Imprimer Le Monde’ is on view until 19 June. For more information, visit the Centre Pompidou website

ADDRESS

Centre Pompidou

Place Georges-Pompidou

75004 Paris

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Japan in Milan! See the highlights of Japanese design at Milan Design Week 2025

Japan in Milan! See the highlights of Japanese design at Milan Design Week 2025At Milan Design Week 2025 Japanese craftsmanship was a front runner with an array of projects in the spotlight. Here are some of our highlights

By Danielle Demetriou

-

Tour the best contemporary tea houses around the world

Tour the best contemporary tea houses around the worldCelebrate the world’s most unique tea houses, from Melbourne to Stockholm, with a new book by Wallpaper’s Léa Teuscher

By Léa Teuscher

-

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuit

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuitElla Kruglyanskaya’s exhibition, ‘Shadows’ at Thomas Dane Gallery, is the first in a series of three this year, with openings in Basel and New York to follow

By Hannah Silver

-

Olympics opening ceremony: a little Gaga, a lot of spectacle, and universal uplift

Olympics opening ceremony: a little Gaga, a lot of spectacle, and universal upliftHow Paris 2024’s Olympics opening ceremony set spirits – and much else – soaring, embracing the Seine, the streets and the skies. Craig McLean reports

By Craig McLean

-

Paris Design Week 2023: the highlights

Paris Design Week 2023: the highlightsYour essential guide to Paris Design Week 2023, from Maison & Objet to Paris Déco Off, and the best things to see in town as part of Maison & Objet City

By Rosa Bertoli

-

Step by step: Virgil Abloh, Jaime Hayon and more rethink the ladder at Galerie Kreo, Paris

Step by step: Virgil Abloh, Jaime Hayon and more rethink the ladder at Galerie Kreo, ParisA new exhibition at Galerie Kreo, ‘Step By Step’, invites more than 20 designers to rethink the ladder’s classic design

By Hannah Silver

-

Virtually experience the shapes and colours of Pierre Charpin

Virtually experience the shapes and colours of Pierre CharpinTake a digital 3D tour of Pierre Charpin’s show ‘Similitude(s)’ at Paris’ Galerie Kreo that explores colour and geometry

By Ali Morris

-

Re-living Pierre Paulin's 1970s Paris

Re-living Pierre Paulin's 1970s ParisTake a journey to 1970s Paris with Sotheby’s celebration of the work of French designer Pierre Paulin

By Laura May Todd

-

Cultural crossings at Maison et Objet January 2020

Cultural crossings at Maison et Objet January 2020In Paris this January, Maison et Objet (17-21 January) spanned fun rides, poetic performances and a Mediterranean brand launch

By Sujata Burman

-

A new design, fashion and retail experience opens in Paris

A new design, fashion and retail experience opens in ParisNew brand La Manufacture offers French allure and Italian craft under the creative crew of Robert Acouri, Milena Laquale and Luca Nichetto

By Yoko Choy

-

Charles Zana creates unexpected dialogues with 17 paired works in Paris

Charles Zana creates unexpected dialogues with 17 paired works in ParisIn exhibition Utopia, Charles Zana turns Tornabuoni Art in Paris into a salon of intimate conversations between Italy’s greatest post-war artists and architects

By Benoit Loiseau