From captive to captivator: the RA's Tim Marlow recalls his adventures with Ai Weiwei

Ai Weiwei on art, architecture, politics and the internet...

Working with Ai Weiwei was one of the most exhilarating experiences of my life. Partly because we had barely a year to make a major exhibition at the Royal Academy, but mainly because he’s a profound, uncompromising and heroic individual whose humanity and humour are never far away.

Outside his studio in Caochangdi – a kind of artists’ village in Beijing – the street is lined with surveillance cameras, each one festooned with a red Chinese lantern by Weiwei, the most gentle of subversions. A bike was chained to the lamppost outside the main door – and it had a fresh bunch of flowers in its basket every day until he got his passport back. For most of the time we were working together, it seemed unlikely he would be able to come to London. I went to Beijing five times over the year and every trip I’d ask whether there was any change in attitude from the Chinese authorities. ‘I always remain optimistic, but every time I think the police might return my passport I am disappointed. Perhaps I am naive,’ he told me.

I remembered his exhibition at the 2013 Venice Biennale, soon after his release from prison, where his mother had come instead. Would she, I wondered, be able to come to London if he were unable to travel. ‘She’s too frail now,’ he said. ‘How about your son?’ I asked. ‘I know he’s only six, but maybe he would like to come.’ ‘My son hates London,’ he told me, rather devastatingly. ‘When I was imprisoned I didn’t want him to know details, so he was told Daddy is in London.’

At the end of July 2015, Weiwei got his passport and was able to come to London – although some jobsworth in the British Embassy in Beijing nearly threw a spanner in the works by refusing him a full visa on the basis that he’d not declared a criminal conviction. (He was never charged, let alone convicted, but that’s another story.) His son, Ai Lao, came too. The usually controlled Weiwei told me how emotional it was seeing his first exhibition in the flesh for more than five years. I asked Ai Lao what he thought of the show. He thought for some time and then said, ‘There is nothing wrong with this exhibition.’ His father told me that was the highest praise his son ever gave. ‘Is there anything wrong with London?’ I asked – the boy shook his head. The city was redeemed.

The night before the exhibition opening, we were walking through the RA courtyard on the way to Chinatown for dinner. In the twilight, we saw a young couple sitting in the black marble armchair Weiwei had installed together with nine remarkable ancient composite trees. As we got close, I realised they were in a deep embrace. Weiwei took out his camera and photographed them. The man looked up and I thought he was about to give us a volley of abuse. ‘This is the artist,’ I said, rather randomly. His face lit up. ‘I love your work,’ he exclaimed. ‘I love yours,’ said Weiwei. ‘Carry on!’ Which they duly did.

Since your return to China from the US, how has your artistic practice changed? In the US, I was interested in art related to ideas and concepts, and surrealism and Dada, which were the movements most related to our human thinking. After I returned to China, it was a completely different situation. China was still under severe censorship. Communist ideology is against freedom of expression. I began to organise underground books and curate exhibitions to promote the local culture. From 1993 to 2003, I basically could not show anything, except to be involved in the underground. In 2004, I had the first opportunity to exhibit in Switzerland and that restarted my so-called career as an artist. Your architecture has attracted high-profile fans like Lord Foster. Have you ever viewed yourself as an architect? What is architecture’s relationship to the practice of your art? I am an architect by nature. Just as I am a political activist by nature, or an artist by nature. To build is a natural human act. I cannot distinguish much between architecture and art. One might be more practical while the other is more about aesthetic or moral arguments, but they are the same. What role does politics play in your work? Our philosophy of how we look at the world is deeply related to our aesthetics. Sometimes, in certain political conditions, one character can become more pronounced than the others. However, they are all related. Even the most political statement requires a form or language to be acceptable, or expressed clearly. That is why the internet is so important. It plays a big role in my work because it gives an individual like myself a clear identity and way of communication. Ai Weiwei is one of our 20 Game-Changers. Read about the other 19 here As originally featured in the October 2016 issue of Wallpaper (W*211)

Ai Weiwei on art, architecture, politics and the internet...

Since your return to China from the US, how has your artistic practice changed? In the US, I was interested in art related to ideas and concepts, and surrealism and Dada, which were the movements most related to our human thinking. After I returned to China, it was a completely different situation. China was still under severe censorship. Communist ideology is against freedom of expression. I began to organise underground books and curate exhibitions to promote the local culture. From 1993 to 2003, I basically could not show anything, except to be involved in the underground. In 2004, I had the first opportunity to exhibit in Switzerland and that restarted my so-called career as an artist. Your architecture has attracted high-profile fans like Lord Foster. Have you ever viewed yourself as an architect? What is architecture’s relationship to the practice of your art? I am an architect by nature. Just as I am a political activist by nature, or an artist by nature. To build is a natural human act. I cannot distinguish much between architecture and art. One might be more practical while the other is more about aesthetic or moral arguments, but they are the same. What role does politics play in your work? Our philosophy of how we look at the world is deeply related to our aesthetics. Sometimes, in certain political conditions, one character can become more pronounced than the others. However, they are all related. Even the most political statement requires a form or language to be acceptable, or expressed clearly. That is why the internet is so important. It plays a big role in my work because it gives an individual like myself a clear identity and way of communication. Ai Weiwei is one of our 20 Game-Changers. Read about the other 19 here As originally featured in the October 2016 issue of Wallpaper (W*211)

INFORMATION

For more information, visit Ai Weiwei’s website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Kapwani Kiwanga transforms Kvadrat’s Milan showroom with a prismatic textile made from ocean waste

Kapwani Kiwanga transforms Kvadrat’s Milan showroom with a prismatic textile made from ocean wasteThe Canada-born artist draws on iridescence in nature to create a dual-toned textile made from ocean-bound plastic

By Ali Morris

-

This new Vondom outdoor furniture is a breath of fresh air

This new Vondom outdoor furniture is a breath of fresh airDesigned by architect Jean-Marie Massaud, the ‘Pasadena’ collection takes elegance and comfort outdoors

By Simon Mills

-

Eight designers to know from Rossana Orlandi Gallery’s Milan Design Week 2025 exhibition

Eight designers to know from Rossana Orlandi Gallery’s Milan Design Week 2025 exhibitionWallpaper’s highlights from the mega-exhibition at Rossana Orlandi Gallery include some of the most compelling names in design today

By Anna Solomon

-

Ai Weiwei at the Design Museum: a snapshot of design history across eight millennia

Ai Weiwei at the Design Museum: a snapshot of design history across eight millenniaAi Weiwei digs deep into design history, gathering everything from Neolithic tools to Lego bricks for his new show at London’s Design Museum. We visit him at home in Portugal for a preview

By TF Chan

-

Making it: with a thriving ‘maker’ culture, Shenzhen is becoming a creative capital of China

Making it: with a thriving ‘maker’ culture, Shenzhen is becoming a creative capital of ChinaBy Karta Healy

-

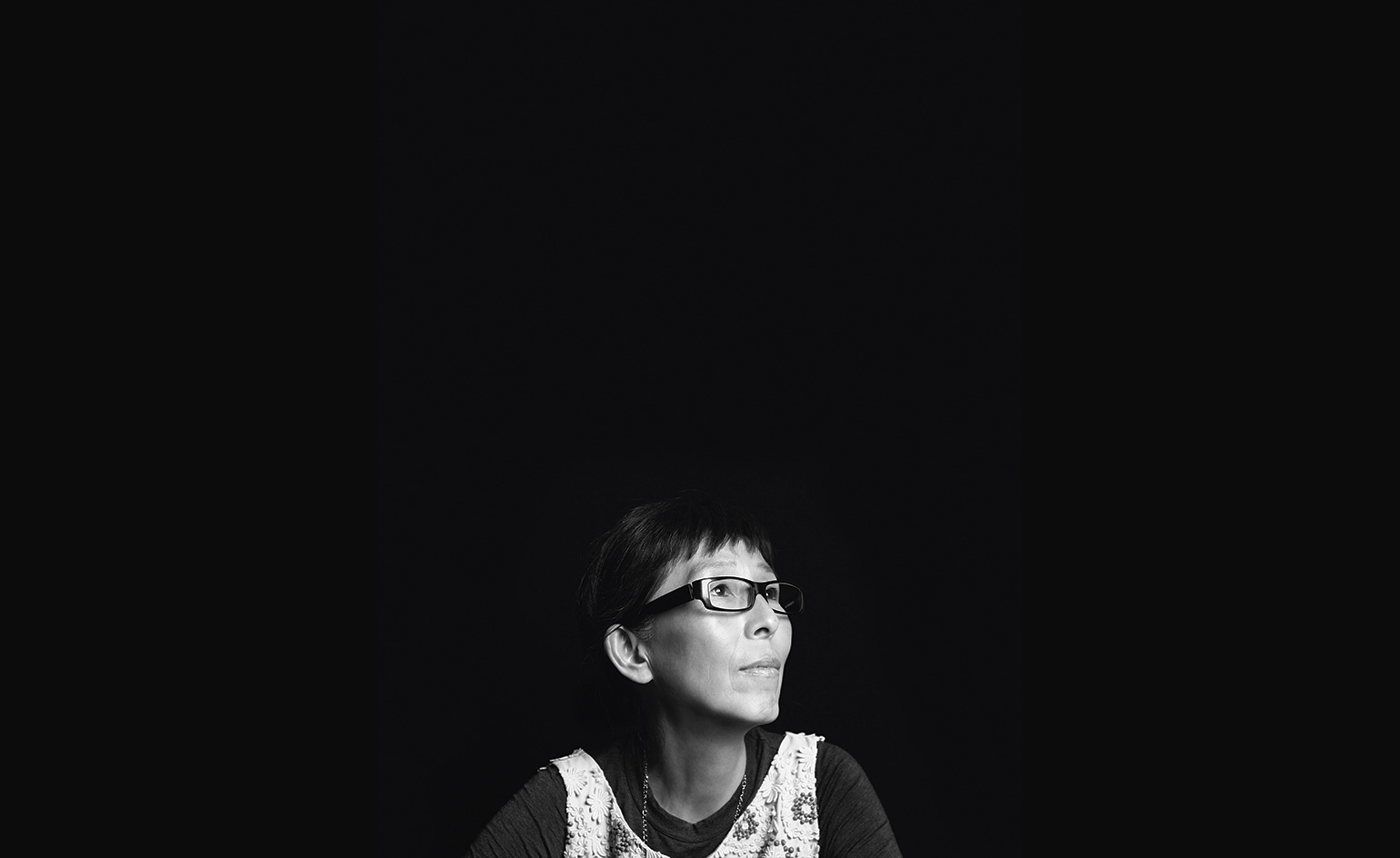

Kazuyo Sejima: from light engineer to architectural heavy hitter

Kazuyo Sejima: from light engineer to architectural heavy hitterBy Ellie Stathaki

-

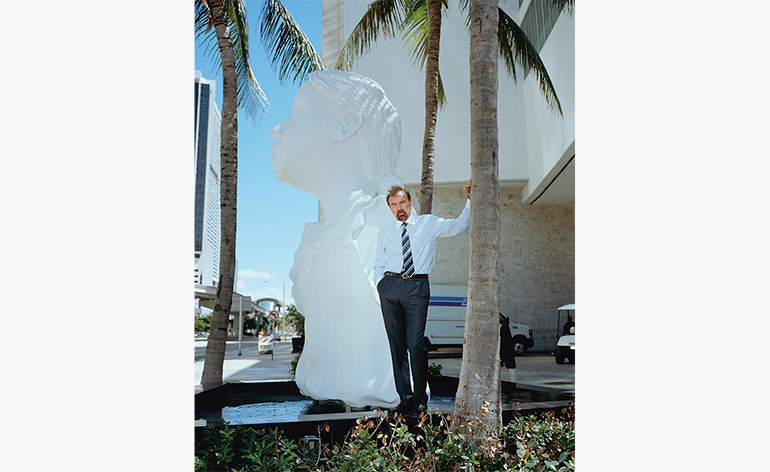

Jorge Pérez: from Miami mogul to Cuban art champion

Jorge Pérez: from Miami mogul to Cuban art championBy Pei-Ru Keh

-

Multi-platform player: Hussein Chalayan lends new form to film, dance and art

Multi-platform player: Hussein Chalayan lends new form to film, dance and artBy Rosa Bertoli

-

Bernardo Paz: from mining magnate to gardener of earthly delights

Bernardo Paz: from mining magnate to gardener of earthly delightsBy Rainbow Nelson

-

Game-Changers: we pick our top 20 creative world-rockers

Game-Changers: we pick our top 20 creative world-rockersIn 20 remarkable years we have come across, written about, examined and exhumed a lot of remarkable people. On the following profiles are 20 of them. This, though, is not a simple ranking of power and influence. These are stories that resonate, with which we find common purpose and cause. Here are people who have sometimes stuck bloody-mindedly to a course, sometimes pivoted, re-examined and pushed in new directions, who have defied expectations and even open derision. They have shown courage under fire and grace under pressure. They have transformed – from girl group popette to one of the fashion industry's smartest operators, for instance – and, over the last 20 years, have had a transformative influence in their field. Here are architects who build with a sense of the immaterial, artists who want to talk to everyone, experimentalists and food engineers, fashion designers who defy fashion and bob and weave like prize fighters, tech titans who have changed the way we do almost everything. One reinvented the hotel industry, another presents it with an existential threat. There is also a man who wants to save the world – or take us all to Mars if that doesn't work out. Either way, we'll be along for the ride.

By Rosa Bertoli

-

From G-man to gentleman: Gucci creative directors, Tom Ford and Alessandro Michele, divided by two decades

From G-man to gentleman: Gucci creative directors, Tom Ford and Alessandro Michele, divided by two decadesBy Alex Fury