Diversity in Design: a new collaborative initiative

Led by Herman Miller, 20 American design organisations are joining forces to level the playing field for underrepresented communities. Their first step: enabling more Black youth to pursue careers in design. We take a first look at this ambitious initiative that promises to change our industry for the better

Herman Miller Group has unveiled the Diversity in Design (DID) collaborative, pulling in 19 other American design organisations who are united in the goal of increasing diversity in the design fields. Sharing the belief that design plays a critical role in creating strong, impactful businesses, DID and its members are committed to forging systemic change, while recognising that this requires long-term strategic action and financial support.

Of all the wake-up calls of 2020, the racial awakening that surged in the United States following the murder of George Floyd, and then rippled across the world, was unequivocally overdue. A wave of social media support prompted individual reckonings, a shared sense of urgency, and a general commitment to do better. But the question of how to achieve long-lasting change remained, for the most part, unanswered.

Black representation and inclusivity in design

Diversity in Design aims to increase Black representation in the US design industry by unlocking opportunities for internships, apprenticeships and long-term employment. Artwork: D’Ara Nazaryan

Racial imbalance, particularly the under-representation of the Black community in the American workforce, is staggering. According to statistics from the US Census Bureau, 12 per cent of the US labour force identify as Black, and less than 5 per cent of designers employed on a full-time basis identify as Black. This includes anyone who listed their profession as commercial and industrial designers, graphic designers, interior designers, landscape architects, urban and regional planners, web and digital interface designers, architects, or simply, designers. To say that the racial inequality in the design industries needs to be corrected is an understatement.

‘When the movement for social justice was reignited a year ago, Herman Miller took a hard look at what we could do better and differently. It was clear in feedback from our employees that we weren’t always moving the needle in meaningful ways, and that our behind-the-scenes approach to diversity, equity and inclusion was limiting our impact,’ recalls the company’s president and CEO Andi Owen. ‘We brought together a group of leaders who put together a series of actions that we’d take to become more diverse, equitable and inclusive within our company, across our industry, and in our communities. Part of those actions was establishing a design collaborative. We knew that the talent funnel for Black designers was broken, and we also knew we could not fix this alone. We committed to partnering with other businesses that put a high value on design, to launch a collaborative aimed at creating design career pathways for under-represented students.’

Black Americans constitute 12 per cent of the US labour force. And less than 5 per cent of designers employed on a full-time basis in the country identify as Black

While DID will eventually address all forms of inequity in the creative industries, its first priority is addressing the under-representation of Black designers. It will create joint initiatives with member corporations, while also fostering design awareness and education at the middle school, high school and college levels. This will be done by working with historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), community colleges, higher learning programmes and non-profit organisations that serve Black youth, so that they can participate in DID’s initiatives, from internships and apprenticeships, to part-time and full-time employment.

Diversity in Design: first steps through education

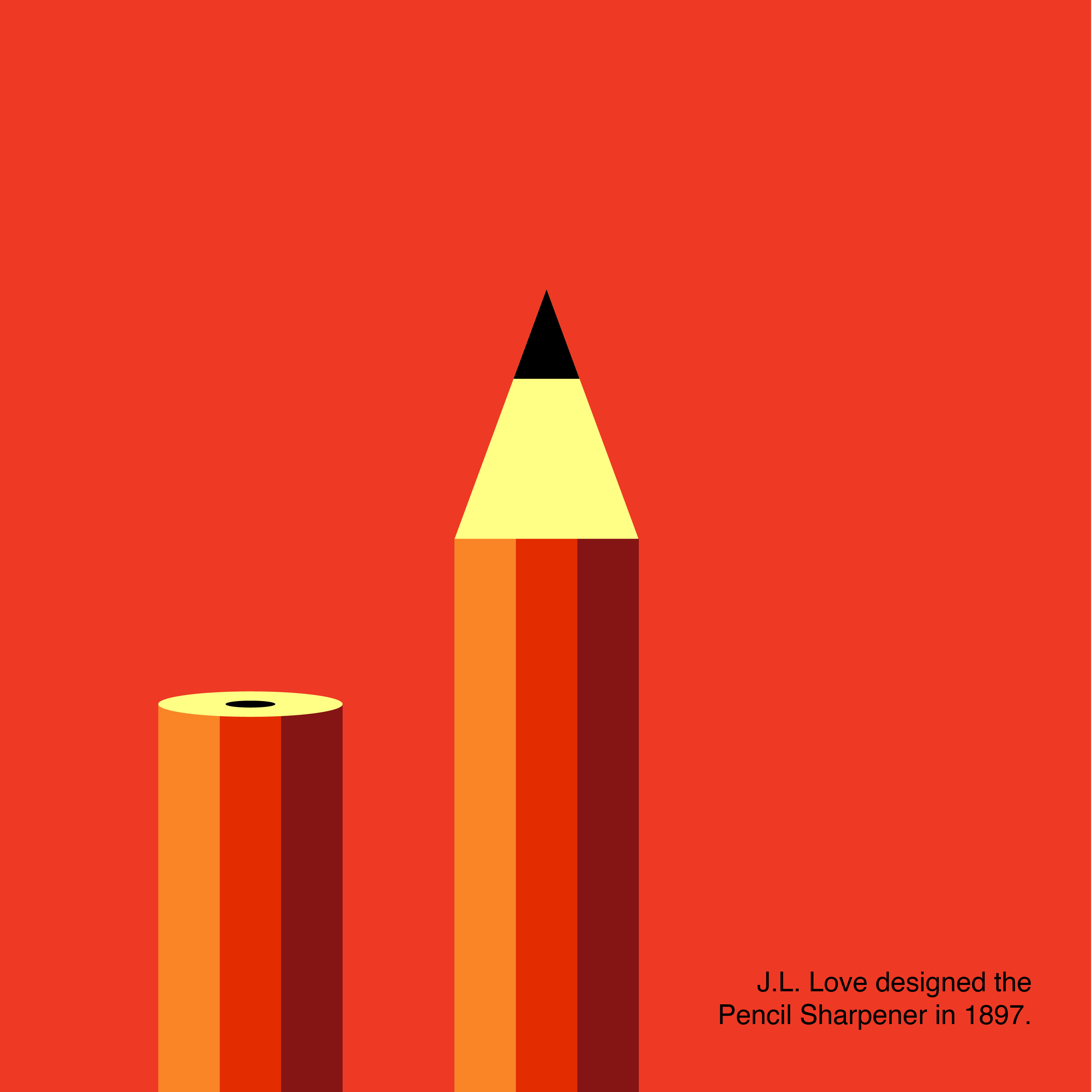

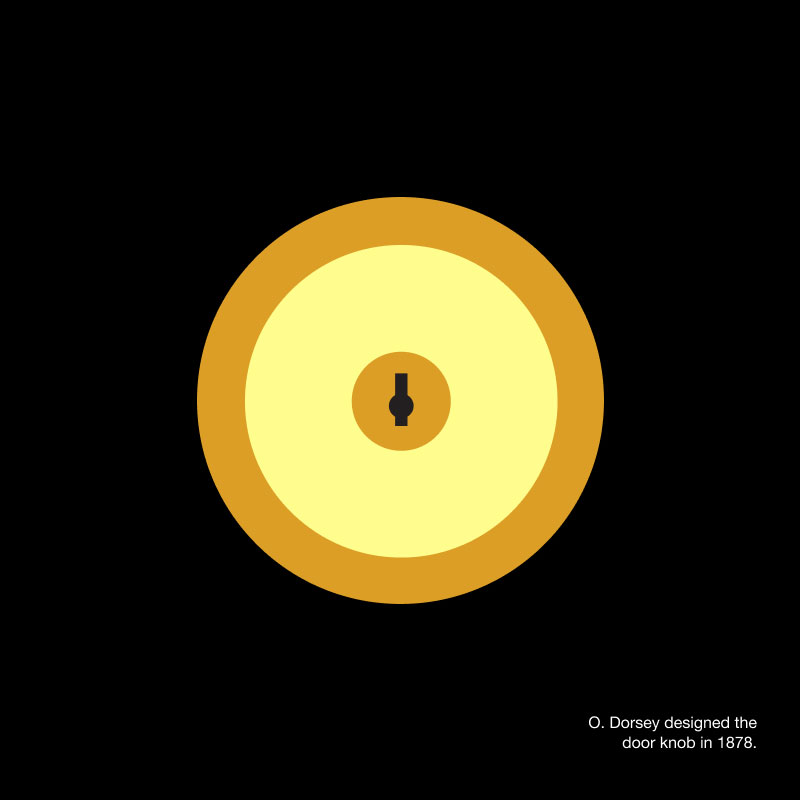

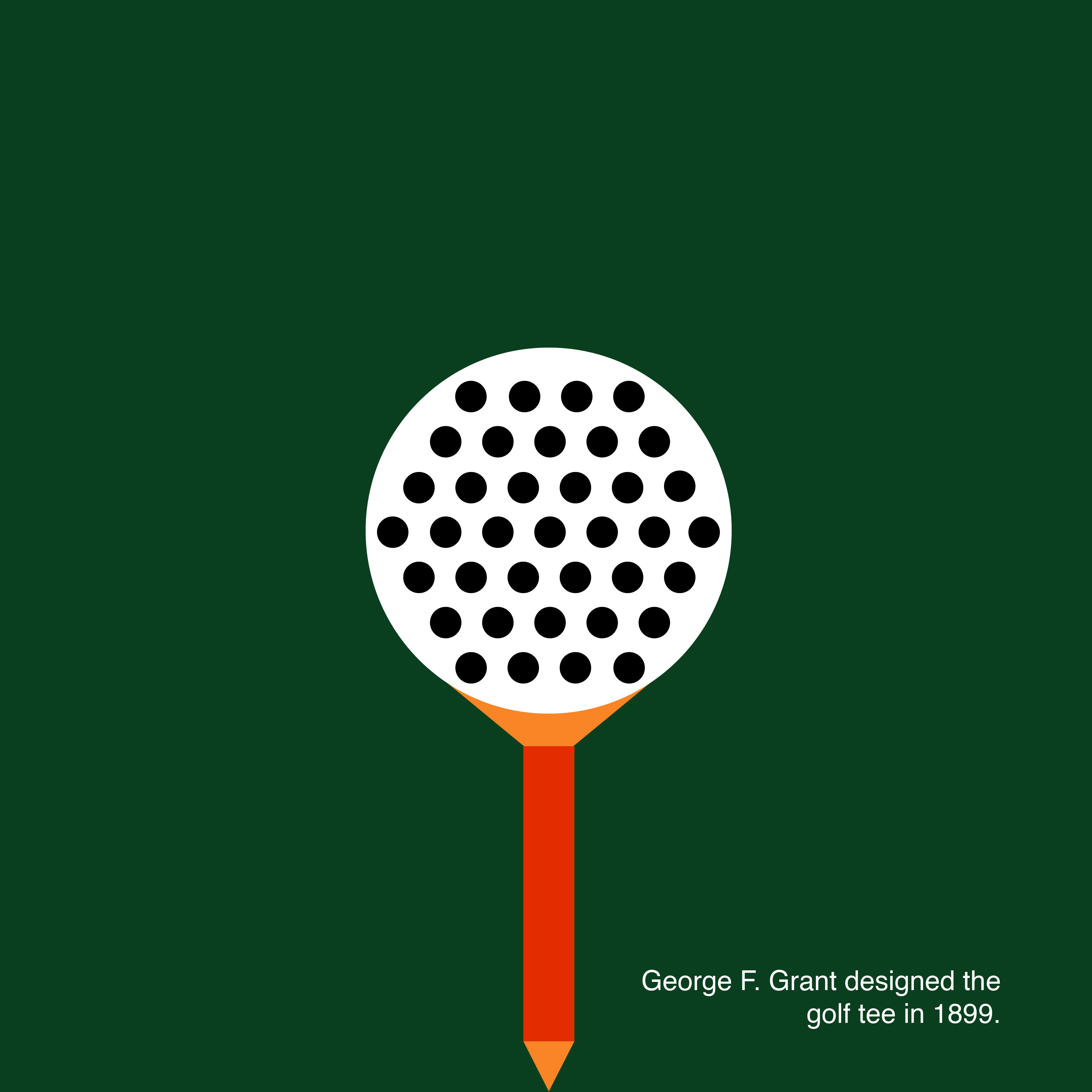

An illustration created by Forest Young, chief creative officer of the brand consultancy Wolff Olins. Young created the ‘Diversity in Design’ logo, and has also art directed this series of images (above and further below), created by Kelly O’Hara and featuring notable Black innovations throughout history

To structure the programme, Herman Miller’s senior vice president of special projects Mary Stevens enlisted Caroline Baumann, former director of the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, to co-lead DID’s creation. Together, they approached key leaders from different fields of design to assemble the inaugural group of member organisations. They also recruited a trio of founding advisors to ensure the collaborative would make a significant impact: D’Wayne Edwards, founder of Pensole Academy, an independent design school dedicated to footwear design; Lesley-Ann Noel, associate director of Design Thinking for Social Impact at Tulane University, and Forest Young, chief creative officer of the brand consultancy Wolff Olins.

‘Part of the germination for DID was seeing press releases from all the big design companies saying, this is what we’re doing, we’re committing this many millions to diversify the industry. And that’s good work, I’m not pooh-poohing it,’ Baumann admits. ‘However, what is design about? Successful design is about joining hands, it’s about experimentation. It’s about collaboration. Once we started pitching this idea to design firms, many of which had already participated in the design education programmes at Cooper Hewitt, everyone was saying yes. It became super clear that the collaborative was the only way to go in making diversity a reality.’

She continues, ‘Black people account for 4.9 per cent of the design industry. All because there’s no pathway. There are sophomores and juniors in high school who have no idea what the concept of designing is, and they certainly don’t know that there are careers in design. Design is not in the classroom as widely as it needs to be.’

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘Access is an issue that we can all work together to overcome’ – Lesley-Ann Noel, associate director of Design Thinking for Social Impact at Tulane University

By targeting the educational pipeline, DID tackles the issues of under-representation at its roots. ‘As a professor of design, who has not taught any Black students in the last two years, and only three students of colour in total, I’m very excited about this initiative. Access is an issue that we can all work together to overcome,’ says Noel, who has helped to build Tulane University’s design thinking programme since 2019 (and will join North Carolina State University’s College of Design this autumn).

Using education: the Pensole experience

Fellow DID advisory council member Edwards, a self-taught designer, agrees. ‘When I first got into the footwear industry in 1989, I was only the second Black person to be at that company. I was one of two people at LA Gear – me and the janitor. That wears on you,’ he shares. ‘And over time, you get to the biggest brand there is, and you still see the lack of diversity. You’re at the biggest company and it’s still fewer than 20, out of well over 300 designers.’

Formerly footwear design director of Nike’s Air Jordan brand, Edwards walked away at the pinnacle of his career to establish Pensole, an academy that nurtures the next wave of young footwear designers. Funded through partnerships with some of the biggest footwear brands, Pensole teaches the entire footwear, materials and functional apparel design process. Pensole’s courses are taught by the industry’s best, and are free to accepted students, regardless of socio-economic background and financial standing. It has placed over 475 graduates in professional positions at companies such as Nike, Adidas, Allbirds and Timberland since it graduated its first class in 2010.

‘Once I got out of the industry, I was able to see the rest of the companies, and really see how bad it was. That validated me leaving in the first place,’ Edwards recalls. At his insistence, Pensole does not advertise or approach brands for collaboration. ‘Not from an arrogant point of view. But if you’re approaching us, that means you really want to work with us. And our approach with students is the same. We don’t try to sell students on what we’re doing. If you really want to do this, you’re going to find us.’

‘Industries have the option of looking the other way or not addressing something. But I can’t turn off being Black. I don't have that option’ – D’Wayne Edwards, founder of Pensole Academy

The year 2020 turned out to be pivotal for Edwards and Pensole. ‘Finally, it wasn’t just the footwear industry that realised there was a problem. All of design realised there was a problem.’ It was a marked contrast from the recent past, when ‘industries have the option of looking the other way or not addressing something’, he says. ‘But I can’t turn off being Black. I don't have that option.’

‘What attracted me to the DID collaborative was that they got it. Herman Miller got it. They figured out that in their small world, there’s a huge lack of diversity. They also realised that there’s strength in numbers and knew this could be addressed in a much bigger way by bringing people together with the same common goal and the same vision,’ he adds. ‘This is what I’ve been hoping for. For 32 years, I've been waiting for our industry to wake up and really come together and figure out a plan to show these kids that there are other things. That there are other relationships they can have with these brands, besides buying products. Because that’s the only relationship right now. What we’re trying to do with DID is to remove the brand part of the equation and do cooperative things together.’

The advisory council: drawing from lived experiences

The beauty of DID’s advisory council is that each member brings a different set of lived experiences that buck the norm. Noel, who comes from Trinidad and Tobago, grew up after the country’s Black Power Revolution and had limited experience of racial injustice until she arrived and began teaching in the United States. Edwards, who grew up in the inner city of Inglewood, California, didn’t let his lack of access to formal schooling, design training and opportunity prevent him from becoming a top footwear designer in the corporate world. Forest Young, DID’s third advisory council member, took a more conventional path, attending an Ivy League school (Yale), becoming a lauded graphic designer, and rising to the C-suite at an international design agency. Raised by activist parents and surrounded by Black artists and creatives since youth, he endured and overcame a more nuanced range of challenges.

‘It’s kind of like the Avengers and we’ve all had different laboratory accidents,’ jokes Young. ‘D’Wayne is fascinating for me because he is focused on looking at the gaps in university education and professional preparedness. And it’s really interesting reflecting with Lesley-Ann because where she comes from, she isn’t a minority or under-represented. She's almost like this alien who’s come in to observe race relations.’

‘I can think from both sides of the room,’ he continues. ‘When I entered the professional industry, I realised I was strange, but not because no one looks like me. That was actually not that unusual, and it hasn’t been throughout my education. I felt like a minority in the sense that I was able to think in terms of the strategy, craft and psychology that you need to shape a project. I realised that was going to be an incredible advantage. And then when you realise that people also underestimate you, that is just the best gift in the world.’

Creating longlasting change through industry participation

With Young rooted in the corporate world, Noel in higher education, and Edwards straddling both, the trio’s understanding of representation is truly multifaceted. ‘There are studies that discuss the type of stresses of being an under-represented minority in art school, while receiving critical feedback from people who aren’t understanding your lived experiences, what you’re doing typographically, or why you’re using form language that’s coming from a different place. It doesn’t all have to be Eurocentric,’ reiterates Young, who also teaches at Yale and Rhode Island School of Design.

‘Part of branding is representation. How can brands actually be successful if you have a largely homogenous group of people at work? I see a fully realised design industry profession as encompassing different views, ages, races and genders. We need to reframe diversity as something to be enthusiastic about. Diversity is our greatest advantage in our international economy, and we talk about it as something reparative or something that is reconciling something for a past wrong. And while that is of course true, how do we reframe it as a pivotal moment that unlocks the potential of our economy and society?’

‘I see a fully realised design industry profession as encompassing different views, ages, races and genders. We need to reframe diversity as something to be enthusiastic about’ – Forest Young, chief creative officer, Wolff Olins

DID is on track to address all that head on. Companies including Adobe, Dropbox, Gap, Knoll, Pentagram, Fuseproject and Levi’s have signed up as founding members. Not only should members abide by a shared code of governance, they should also create opportunities through recruitment and retention, promote awareness, and participate in educational programmes and initiatives.

Levi’s, which already has a legacy of advocating for equality and supporting local communities, was drawn to the idea of solidarity in numbers. Elizabeth Morrison, the company’s chief diversity, inclusion and belonging officer says, ‘DID is incredibly exciting, primarily because the effort is collaborative, spans industries, and encompasses a broad diversity of companies and organisations. We have so much more power together! Creative fields like fashion, design, artistic creation are rarely the focus of diversity initiatives, and in fact, are among the first to be dropped by underfunded schools and educational programmes. Being at the forefront of an effort to reclaim the importance and viability of these areas for under-represented communities is both exciting and meaningful.’

Diversity in Design: next steps

She adds that fostering diversity will not only allow Levi’s to ‘welcome new perspectives and perceptions’, but to also ‘authentically reflect our fans and the communities where we live and work’. In 2022, the first DID Design Fair will take place in Detroit, specifically targeting teenagers interested in design and careers in design. DID will also support a new partnership between Pensole and the College of Creative Studies (CCS) that will create focused business and design education for Black college students. By setting students up with the foundation, experience and skills needed for successful design careers, the joint effort will create a pipeline for companies with an emphasis on diversity recruiting.

‘For me, what justice looks like is levelling the playing field. We’re not looking for handouts or any special treatment. Just allow us to start at the same starting line,’ says Edwards. ‘I was blessed to have someone who believed in me. Otherwise, at 19 years old, the higher probability was for me to be dead or in jail. I had an outlet. The majority of these kids don’t, and they don’t even see that there’s a company that produces products. Their perception of the footwear industry is the mall. They have no concept that there are people who get paid to design. I’ve been at job fairs and I’ve never seen my job up there. Yes, the world needs firefighters, police officers, doctors, lawyers and accountants, but I made more money than all of those people, so why wouldn’t you have me up there? I’m pretty sure some of these kids will want to be more like me than them, right? It’s really just a lack of awareness. There’s a lot of talent that needs to be cultivated, and DID bridges the gap.’

INFORMATION

This article appears in the August 2021 issue of Wallpaper* (W*269), now on newsstands and available for free download

Pei-Ru Keh is a former US Editor at Wallpaper*. Born and raised in Singapore, she has been a New Yorker since 2013. Pei-Ru held various titles at Wallpaper* between 2007 and 2023. She reports on design, tech, art, architecture, fashion, beauty and lifestyle happenings in the United States, both in print and digitally. Pei-Ru took a key role in championing diversity and representation within Wallpaper's content pillars, actively seeking out stories that reflect a wide range of perspectives. She lives in Brooklyn with her husband and two children, and is currently learning how to drive.

-

Marylebone restaurant Nina turns up the volume on Italian dining

Marylebone restaurant Nina turns up the volume on Italian diningAt Nina, don’t expect a view of the Amalfi Coast. Do expect pasta, leopard print and industrial chic

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Tour the wonderful homes of ‘Casa Mexicana’, an ode to residential architecture in Mexico

Tour the wonderful homes of ‘Casa Mexicana’, an ode to residential architecture in Mexico‘Casa Mexicana’ is a new book celebrating the country’s residential architecture, highlighting its influence across the world

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Jonathan Anderson is heading to Dior Men

Jonathan Anderson is heading to Dior MenAfter months of speculation, it has been confirmed this morning that Jonathan Anderson, who left Loewe earlier this year, is the successor to Kim Jones at Dior Men

By Jack Moss

-

From migrating elephants to a divisive Jaguar, was this the best Design Miami yet?

From migrating elephants to a divisive Jaguar, was this the best Design Miami yet?Here's our Design Miami 2024 review – discover the best of everything that happened at the fair as it took over the city this December

By Henrietta Thompson

-

California cool: Studio Shamshiri debuts handmade door handles and pulls

California cool: Studio Shamshiri debuts handmade door handles and pullsLos Angeles interior design firm Studio Shamshiri channels the spirit of the Californian landscape into its handcrafted hardware collections. Founder Pamela Shamshiri shares the inspiration behind the designs

By Ali Morris

-

Is Emeco's 'No Foam KNIT' a sustainable answer to synthetic upholstery textiles?

Is Emeco's 'No Foam KNIT' a sustainable answer to synthetic upholstery textiles?'Make more with less' is Emeco's guiding light. Now, the US furniture maker's new mono-material textile, the 'No Foam KNIT', may offer a sustainable solution to upholstery materials

By Ali Morris

-

Smooth operator: Willett debuts new furniture at Design Miami 2024, with a playful touch of retro allure

Smooth operator: Willett debuts new furniture at Design Miami 2024, with a playful touch of retro allureLA furniture designer Willett turned heads in the design world with the launch of his eponymous brand earlier this year. Ahead of his Design Miami debut, he told us what’s in store for 2025

By Ali Morris

-

Forged in the California desert, Jonathan Cross’ brutalist ceramic sculptures go on show in NYC

Forged in the California desert, Jonathan Cross’ brutalist ceramic sculptures go on show in NYCJoshua Tree-based artist Jonathan Cross’ sci-fi-influenced works are on view at Elliott Templeton Fine Arts in New York's Chinatown

By Dan Howarth

-

Italian designer Enrico Marone Cinzano fuses natural perfection with industrial imperfection

Italian designer Enrico Marone Cinzano fuses natural perfection with industrial imperfectionEnrico Marone Cinzano's first solo show at New York’s Friedman Benda gallery debuts collectible furniture designs that marry organic materials with upcycled industrial components

By Adrian Madlener

-

One to Watch: Brooklyn studio Outgoing gives new meaning to the idea of world building

One to Watch: Brooklyn studio Outgoing gives new meaning to the idea of world buildingLife and creative partners Brett Gui Xin and Del Hardin Hoyle from Outgoing blur the lines between craft and concept in experimental designs that have the potential for greater application

By Adrian Madlener

-

Discover the alchemy of American artists Philip and Kelvin LaVerne

Discover the alchemy of American artists Philip and Kelvin LaVerneThe work of Philip and Kelvin LaVerne, prized by collectors of 20th-century American art, is the subject of a new book by gallerist Evan Lobel; he tells us more

By Léa Teuscher