Early show: a New York exhibition celebrates Sottsass' pre-Memphis moves

For the first time ever in the US, Friedman Benda gallery in New York is displaying Ettore Sottsass’ diverse early-career oeuvre of cermaics, furniture, lighting and photographs. Pictured: Marc Benda, holding a vase from the Tenebre Series, designed by Sottsass in 1963. Also by Sottsass, from left, ’Califfo’ sofa, 1965; ’Offerta a Shiva’ plates, 1964; Library, 1965; vases from Lava Series, 1957, Rocchetti Series, 1957–1959, and Tenebre series, 1957–1959

Looking back on his early experiments with ceramics, Ettore Sottsass recalled mucking about in the 1950s with crude Tuscan clay and cold overglaze enamels – materials that connected him to a tradition of wares ‘made for eating pea soup and potatoes on the large wooden tables of convents in the Sienese hills’. The experience pulled him further away from modernism’s refined rationality and closer to humanity – vital yet fragile, alive but imperfect. ‘I began to think that if there was a reason for designing objects,’ wrote the Italian architect and designer in Domus, ‘it was in one way or another to help people live.’

Some fruits of that epiphany are now going on display in the US for the first time in a major exhibition at the newly renovated Friedman Benda gallery in New York. Ten years in the making, the show serves up a rarely seen portion of Sottsass’ diverse output: ceramics, furniture, lighting and photographs from the early stages of his career. Previously only available to institutions, many of the approximately 100 works, which date from 1955 through to 1969, have never before been offered for sale. The show is the result of a decade of hunting down important collections of Sottsass’ work and homes he designed as well as a close collaboration with his estate, which decided several years ago to begin selling selected works, initially exclusively to museums. ‘We are looking for both institutional and private buyers with this exhibition,’ says Marc Benda, who founded the Manhattan gallery with Barry Friedman in 2007. ‘The show should serve to broaden the appreciation and connoisseurship of a discerning collecting audience, but also a wider public.’

A summer makeover has unified Friedman Benda’s Chelsea base, creating a single open space and adding two large windows that open to the street. The more compact arrangement brings a new intimacy to the gallery. ‘It was very much a conscious decision to make the space a bit smaller,’ explains Benda. ‘We want designers to design tight shows.’ The choice to unveil the refurbished space with a Sottsass show was also a deliberate one. ‘He is part of the DNA of the gallery,’ says Benda, who has mounted several previous shows of the designer’s work. ‘I wanted to see the early work in its own context, and when we started putting this exhibition together, we realised that a completely different Sottsass emerged. I think this show will shatter people’s expectations.’

Most surprised will be those who know Sottsass only as the man behind the cherry red Olivetti ‘Valentine’ typewriter of 1969 or as the godfather of the Memphis group, the bright and colourful reinvigoration of Italy’s Radical Design movement. ‘It’s good to remember that he was 64 – nearly retirement age – when Memphis was launched in 1981,’ explains Glenn Adamson, director of New York’s Museum of Arts and Design. ‘It was really a late manoeuvre in a long career, and to the extent that it was an ironic “anti-design” project, it only came after many strongly felt works from earlier years.’

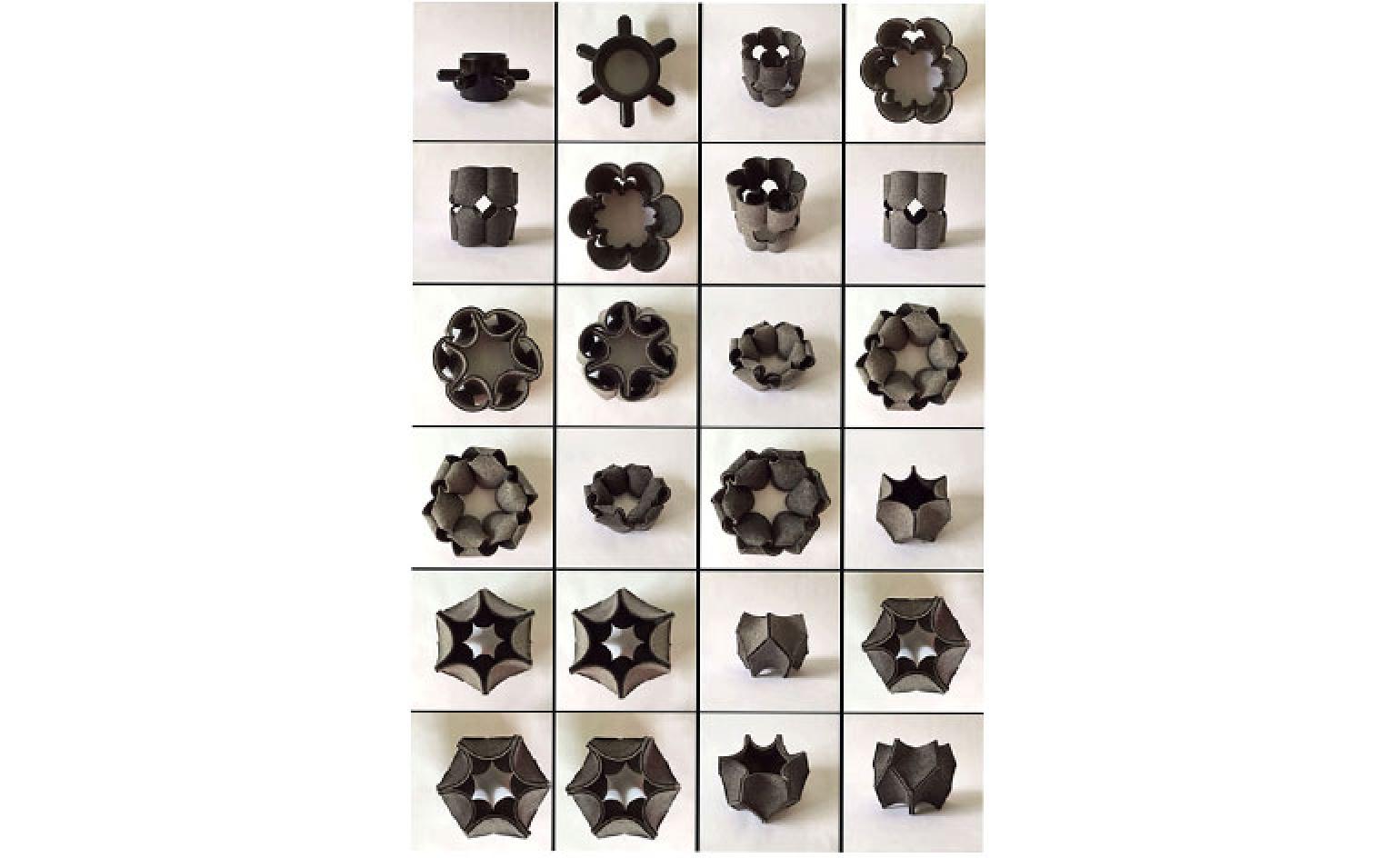

Among those works are the approximately 50 ceramic pieces that are the cornerstone of the exhibition. Discrete sets each attributable to a single year, they show Sottsass exploring form and colour, embracing craft with the humble terracotta he likened to human flesh, and then defying it through the use of industrial enamels. ‘He would collaborate with artisans and companies that would provide the know-how,’ says Benda, ‘but he took this millennia-old material and made things that fit in nowhere but his own vision.’

With ceramics, Sottsass found a way to rediscover archetypal forms: many of his works from the 1950s and 1960s have a symbolic or totemic quality, from the lighting and mirrors he designed for Arredoluce to a sideboard made graphic by rosewood slats. ‘These laid the pathway to postmodern compositional technique, though the vivid juxtaposition of volumes, patterns and colours,’ says Adamson.

Sustaining and enhancing these bold combinations is a mastery of proportions, itself the product of complex decision making. ‘He did everything with intention. Nothing was unconsidered, from the way he arranged the objects on his desk, to the way he dressed, to how he chose the right pencil to draw with, to the consideration of where we all met for lunch,’ says David Kelley, co-founder of design firm Ideo, who counted Sottsass as both a colleague and a friend (and an architect: Kelley lives in a Californian home designed for him by Sottsass Associati). ‘He enjoyed making and designing all these decisions. And from him, I learned how to savour these normal everyday life occurrences.’

This unique combination of decisiveness and playfulness is especially apparent in the interiors and furnishings Sottsass designed during this period. Often enlivened by wall compositions that combined paintings and ceramics, the spaces alternated surfaces and colours in what he once described as ‘an essentially colourful and graphic game, which no longer reflects a structural idea’. The focus at Friedman Benda will be the modular, colourful components of these spaces. Rather than recreate the rooms immortalised in Domus, ‘the exhibition will centre on the works themselves,’ notes Benda, ‘in a contemporary context’.

For the home of a director at Olivetti he created a unique wall-mounted bookcase that Benda snagged for the show. Massive yet somehow sprightly in lacquered wood and walnut, the 1965 design keeps a row of tall, extruded lines in dialogue with human scale. ‘There are certain tenets of modernism that he retains at this moment, but he fiddles with proportions in a way that makes it his own,’ says Benda. ‘With this bookcase, he plays with the vertical versus horizontal in a way that the Scandinavians would never even think of.’

The energy that courses through Sottsass’ work is all the more remarkable for its synthesis and integration of influences – the Dolomites of his childhood, his architectural training, encounters with the likes of Picasso and Ernst, travels in India and North Africa, a stint working for George Nelson, a protracted hospital stay in California – in a way that produces something entirely new, free of apparent references. ‘He’s infusing different cultures, personal experiences. I wanted to mine the enormous amount of information that was left to us and that hasn’t really been attacked,’ says Benda. ‘This is the most intimate show I’ve ever done; it’s almost a dialogue with him.’

‘For many of us in the industrial design profession, Ettore’s legacy will always be that he led a movement that said it’s OK to have fun with what you design,’ says Kelley. ‘He gave us the permission to be personally expressive with what we designed and to make things more human, less rational, and more playful. He taught us that our designs could be less rule-based, imperfect, and messy, and that this approach to design would make people more vital and comfortable. Life is messy and design can also be messy. Our lives could be just a little bit more enjoyable lived Ettore’s way.’

As originally featured in the October 2015 edition of Wallpaper* (W*199)

Coffee table, 1959; ’Tantra’ vase, 1968

’Tempus’ hall cabinet, designed for Poltronova in the early 1960s

Three ’Tantra’ vases, 1968, on a ’Lotto’ Dinning Table in enamelled steel and marble, 1965

Benda holds a unique vase created by Sottsass in 1959

A selection of ceramics from the exhibition, including vessels from the Lava (1957), Rocchetti (1957–1959) and Tenebre series (1963)

’Barbarella’ secretaire, 1966

INFORMATION

‘Ettore Sottsass 1955–1969’ is on view at Friedman Benda until 17 October

Photography: Daniel Shea

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

ADDRESS

Friedman Benda

515 W 26th Street

New York, NY 10001

Stephanie Murg is a writer and editor based in New York who has contributed to Wallpaper* since 2011. She is the co-author of Pradasphere (Abrams Books), and her writing about art, architecture, and other forms of material culture has also appeared in publications such as Flash Art, ARTnews, Vogue Italia, Smithsonian, Metropolis, and The Architect’s Newspaper. A graduate of Harvard, Stephanie has lectured on the history of art and design at institutions including New York’s School of Visual Arts and the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston.

-

The Sialia 45 cruiser is a welcome addition to the new generation of electric boats

The Sialia 45 cruiser is a welcome addition to the new generation of electric boatsPolish shipbuilder Sialia Yachts has launched the Sialia 45, a 14m all-electric cruiser for silent running

By Jonathan Bell

-

Tokyo design studio We+ transforms microalgae into colours

Tokyo design studio We+ transforms microalgae into coloursCould microalgae be the sustainable pigment of the future? A Japanese research project investigates

By Danielle Demetriou

-

What to see at London Craft Week 2025

What to see at London Craft Week 2025With London Craft Week just around the corner, Wallpaper* rounds up the must-see moments from this year’s programme

By Francesca Perry

-

Charles Zana creates unexpected dialogues with 17 paired works in Paris

Charles Zana creates unexpected dialogues with 17 paired works in ParisIn exhibition Utopia, Charles Zana turns Tornabuoni Art in Paris into a salon of intimate conversations between Italy’s greatest post-war artists and architects

By Benoit Loiseau

-

Over 150 Ettore Sottsass ceramics go on view at Phillips in London

Over 150 Ettore Sottsass ceramics go on view at Phillips in LondonBy Ali Morris

-

Ettore Sottsass’ designs go up for auction in Paris this autumn

Ettore Sottsass’ designs go up for auction in Paris this autumnBy Alice Bucknell

-

A Memphis-inspired hotel suite in New York has its interiors up for sale

A Memphis-inspired hotel suite in New York has its interiors up for saleBy Sujata Burman

-

A show of early Ettore Sottsass ceramics unites two titans of 20th-century design

A show of early Ettore Sottsass ceramics unites two titans of 20th-century designBy Emma Moore

-

Glass act: a Venice exhibition reveals a never before seen side of Ettore Sottsass

Glass act: a Venice exhibition reveals a never before seen side of Ettore SottsassBy Ali Morris

-

Bowie’s bounty: Sotheby’s presents ’Bowie/Collector’ exhibition and auction

Bowie’s bounty: Sotheby’s presents ’Bowie/Collector’ exhibition and auctionBy Simon Mills

-

Made in Mexico: Gala Fernández takes over NYCxDesign with sculptural pieces

Made in Mexico: Gala Fernández takes over NYCxDesign with sculptural piecesBy Emma O'Kelly