Formafantasma's tiles rise from the ashes of a Sicilian volcano

‘This is a collaboration between Mount Etna and us,’ says Simone Farresin, one half of Amsterdam-based design duo Formafantasma. He’s in Sassuolo, Italy, with the other half Andrea Trimarchi, to wrap up a three-year project to transform ash from the Sicilian volcano into tiles for Dzek, the architectural materials company founded by Brent Dzekciorius in London in 2013.

‘We always think that, as designers, we have to decide things, but the world also decides things for us,’ says Farresin. In this case, the ferrous colours and final tile format were determined by Mount Etna. Volcanic ash is the grainy aftermath of molten magma that has erupted from under the planet’s crust. Thrust through the volcano’s crater into the atmosphere, the airborne lava cools into jagged particles of rock, minerals and obsidian glass that fall to earth. Whereas basalt and pumice, the rocky masses formed by igneous rivers of terrestrial lava, have been mined for centuries as building blocks, volcanic ash proved too non-uniform a material, but Formafantasma and Dzek saw a chance to expand the vocabulary of the volcano.

Volcanic ash being sieved to give consistency of grain size.

Chemical tests revealed that blowing glass from the volcanic ash would require introducing additives, contrary to their concept of a purely volcanic obsidian, so they experimented instead with glass bricks, which proved too brittle, and then clay bricks coated in glass, installing a wall of them in Columbus, Indiana, and producing, in the process, a lot of broken bricks and cut hands. Finally, they created non-reactive porcelain tiles with a glaze of melted volcanic ash on top, the version they’ll present in Milan this year. ‘We’re not the kind of designers that send drawings and that’s it. We’re deep into the process of developing the work,’ says Trimarchi. ‘The failures lead you to places your ego never would have taken you,’ adds Farresin. ‘And Brent understood that if something is more process-based, you have to have the patience for it.’

The failures lead you to places your ego never would have taken you

Simone Farresin

At the factory, amid the plastic buckets of pigment and trays of unfired biscuit, sits a botched batch of the Dzek tiles rolled out of the kiln, which have exploded into pieces because of a moisture imbalance. But to one side are the first successful tiles, the ‘ExCinere’ (Latin for ‘from the ashes’), the gleaming burnished slats fluctuating from caramel to deep sienna, the surfaces flecked with unmelted ash particles.

‘ExCinere’ on view at Alcova in Milan.

For their Milan installation, the tiles will be produced in quantities to cover a section of walls, ceiling and floor, along with columns, cubes, tables and other architectural forms. The high percentage of the ash’s iron content creates a range of browns ‘that make them very 1970s in a way,’ says Farresin. ‘But then sometimes process takes you to unexpected places. We’d been considering pastels and almost artificial colours, but these tones are more like life, and they bring back a quality that’s disappearing in architecture, which is the non-uniformity of colour.’

‘In the post-war buildings of Milan, you can still find rich glazes like this; not like today’s digitally printed tiles,’ says Trimarchi, noting that glazed tiles are the original self-cleaning technology, washed of pollution with each rainfall. The Dzek tiles, made for interior and exterior use, ‘take back the understanding of surface in architecture which, since the 1990s has been very flat, very uniform, very sanitised,’ says Farresin, running a hand over the granular face of a tile. ‘Like traditional ceramics, this is more reactive, more mercurial, but we think that’s the beauty.’

As originally featured in the May 2019 issue of Wallpaper* (W*242)

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Dzek website and the Formafantasma website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Naoto Fukasawa sparks children’s imaginations with play sculptures

Naoto Fukasawa sparks children’s imaginations with play sculpturesThe Japanese designer creates an intuitive series of bold play sculptures, designed to spark children’s desire to play without thinking

By Danielle Demetriou

-

Japan in Milan! See the highlights of Japanese design at Milan Design Week 2025

Japan in Milan! See the highlights of Japanese design at Milan Design Week 2025At Milan Design Week 2025 Japanese craftsmanship was a front runner with an array of projects in the spotlight. Here are some of our highlights

By Danielle Demetriou

-

Tour the best contemporary tea houses around the world

Tour the best contemporary tea houses around the worldCelebrate the world’s most unique tea houses, from Melbourne to Stockholm, with a new book by Wallpaper’s Léa Teuscher

By Léa Teuscher

-

Faye Toogood comes up roses at Milan Design Week 2025

Faye Toogood comes up roses at Milan Design Week 2025Japanese ceramics specialist Noritake’s design collection blossoms with a bold floral series by Faye Toogood

By Danielle Demetriou

-

Aboard Gio Ponti's colourful Arlecchino train in Milan, a conversation about design with Formafantasma

Aboard Gio Ponti's colourful Arlecchino train in Milan, a conversation about design with FormafantasmaThe design duo boards Gio Ponti’s train bound for the latest Prada Frames symposium at Milan Design Week

By Laura May Todd

-

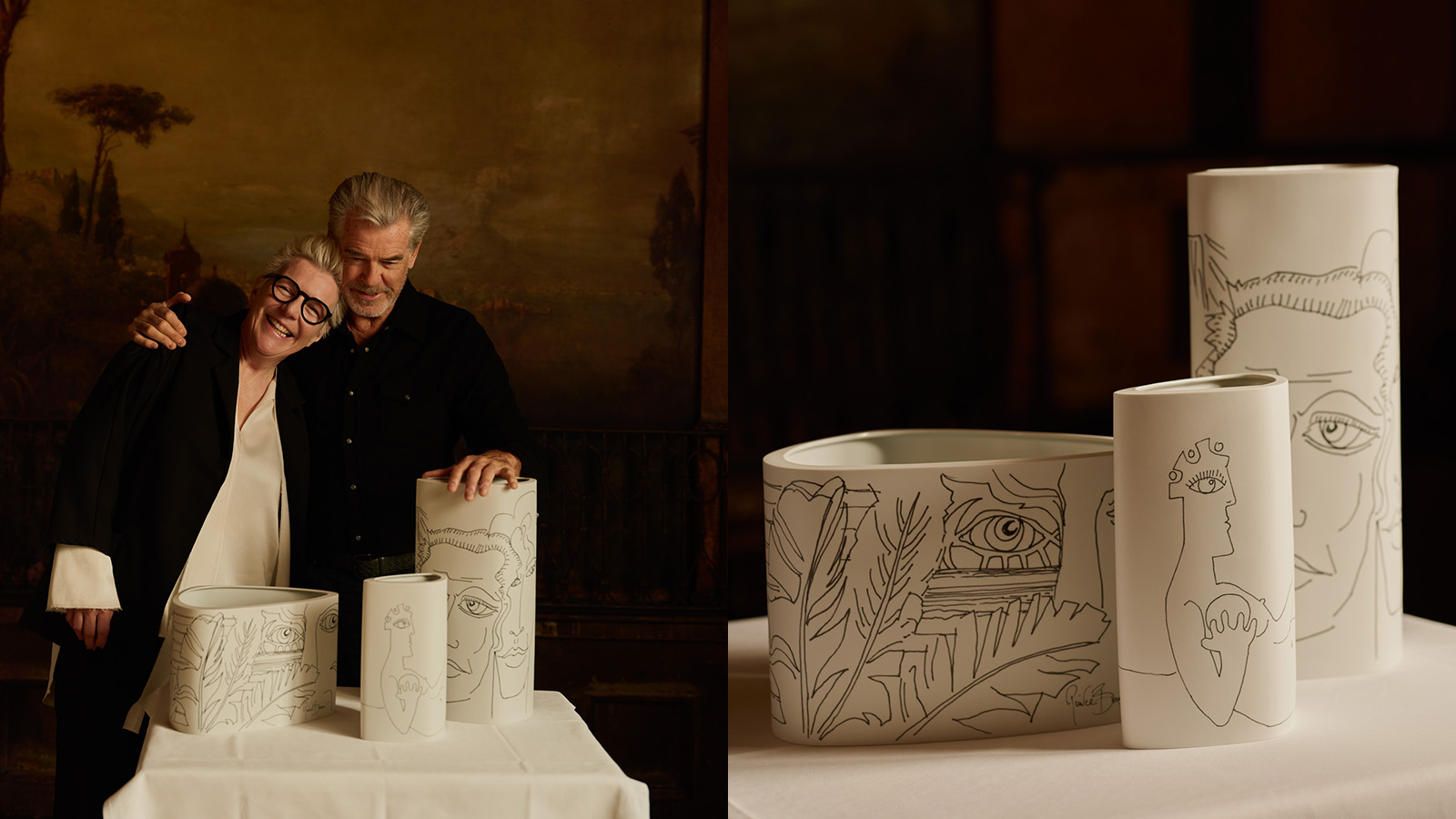

Pierce Brosnan and Hering Berlin's ceramic vases explore love, loss and renewal

Pierce Brosnan and Hering Berlin's ceramic vases explore love, loss and renewalActor and artist Pierce Brosnan translates his ‘So Many Dreams’ artworks to Hering Berlin ceramic vases in a new limited edition

By Tianna Williams

-

Ceramics brand Mutina stages a poetic tribute to everyday objects

Ceramics brand Mutina stages a poetic tribute to everyday objectsDesign meets art as a new Mutina exhibition in Italy reframes the beauty of domestic stillness, juxtaposing ceramics, sculpture, paintings and photography

By Laura May Todd

-

Designer Danny Kaplan’s Manhattan showroom is also his apartment: the live-work space reimagined

Designer Danny Kaplan’s Manhattan showroom is also his apartment: the live-work space reimaginedDanny Kaplan’s Manhattan apartment is an extension of his new showroom, itself laid out like a home; he invites us in, including a first look at his private quarters

By Diana Budds

-

Our highlights from Paris Design Week 2025

Our highlights from Paris Design Week 2025Wallpaper*’s Head of Interiors, Olly Mason, joined the throngs of industry insiders attending the week’s events; here’s what she saw (and liked) at Paris Déco Off and Maison&Objet in the City

By Anna Solomon

-

Florim’s new ceramic surface collection is an ode to tactility

Florim’s new ceramic surface collection is an ode to tactilityA primal pleasure, Matteo Thun and Benedetto Fasciana’s SensiTerre collection of ceramic flooring and cladding surfaces for Florim is a Wallpaper* Design Award winner

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Wallpaper* Design Awards 2025: Formafantasma revisits the masculine codes of modernist design

Wallpaper* Design Awards 2025: Formafantasma revisits the masculine codes of modernist designFormafantasma wins a Wallpaper* Design Award 2025, for its Milan exhibition ‘La Casa Dentro’, which took to task the inherent masculinity and conservatism at the heart of modernism

By Hugo Macdonald