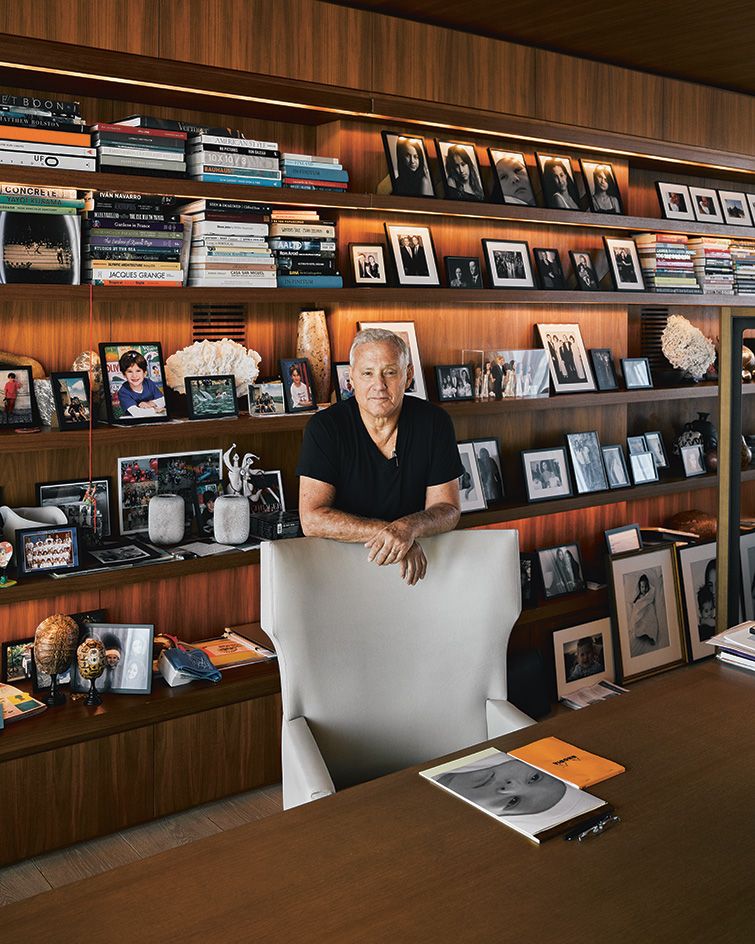

Host with the most: Ian Schrager is the visionary who revolutionised the hotel industry

Most people steal things from hotels. Few try to steal an entire hotel. But that’s what happened to Ian Schrager. Just weeks after he opened the Edition in Waikiki, the owner of the building turned up in the middle of the night, changed the locks on the front doors and told the staff they worked for him now, not Schrager’s company. The episode neatly, if rather dramatically, sums up the man who has transformed hotels.

Over the past 30 years, Schrager has reinvented hotels and then reinvented them some more, and each time he has done so, his rivals, big and small, have stolen his ideas wholesale. At Morgans, the Royalton, the Paramount and the Hudson in New York and, along the way, the Delano in Miami, the Clift in San Francisco, the Mondrian in LA, and St Martin’s Lane and the Sanderson in London, he created the boutique hotel. It got the name not because it was small, but because it was curated with a strong attitude and aesthetic, like a fashion boutique.

The key ingredients are the lobby scene, the go-to bar, the must-book restaurant for guests and locals alike, the signature scents, the hot staff with clothes more expensive than the guests’, the cool nightclub, the sense of an urban resort, the CD collection and the baffling taps in the bathrooms. There’s scarcely a hotel on the planet whose design or service has not borrowed some or all of these elements. ‘They pickpocket my ideas,’ Schrager says. ‘I still get annoyed by it, especially when I see things that we laboured and agonised over that have now become standard. The bed with the low headboard with the light behind, it’s everywhere.’

It’s not just independent hoteliers who have followed him, notably André Balazs of Chateau Marmont, Mercer and Standard fame, and the late Alexander Calderwood, who set up Ace hotels. All the major hotel groups have now established their own boutique brands. Some have several. Starwood’s W is the best known, but there’s also Reserve (Ritz-Carlton), Andaz (Hyatt), Aloft and Element (Starwood), and Edition (Marriott, in a joint venture with Schrager himself, who decided not to get mad but to get even by doing his own boutique chain with the US hotel giant).

Small wonder that Anna Wintour, artistic director of Condé Nast and editor of US Vogue, one of the most influential taste-makers on the planet, describes Schrager as her equal. ‘Ian is a natural at tapping into whatever is going on in culture,’ she says. She also calls him ‘an obsessional control freak’. She means it as a compliment. ‘It takes one to know one,’ Schrager laughs, when we meet for lunch on the terrace of his summer home in the Hamptons. ‘I don’t know anyone successful who isn’t a bit obsessional. All I care about is the product,’ he goes on. ‘It’s only when all the details come together that you get alchemy, so I have to obsess about the details.’

How did he get here? Like Miuccia Prada, who began her professional life as a mime artist rather than a fashion designer, it helped that he did not have a hotel background. ‘Being an outsider was critical because you have to come in from outside to have the perspective to say: “Wait a minute. These hotels are bullshit. They’re not for us any more.” It’s the emperor’s new clothes.’

Schrager trained as a lawyer and started work in New York in 1971. One of his first clients was Steve Rubell, an old university friend whose chain of steak restaurants, Steak Lofts, was going bust and needed protection from its creditors. What happened next was the first act in his business life.

‘Steve said to me one day: “If you are a lawyer, you are always an advisor to someone else. Don’t you want to be the principal?”’ recalls Schrager. ‘I’d wanted to get into the nightclub business for a while because I’d walked the streets and seen lots of people waiting in line to get into nightclubs. Also, there was no barrier to entry. You did not need to have experience. You just had to have an idea.’ After dabbling with a club in Queens called The Enchanted Garden, he and Rubell managed to rent the former Gallo Opera House on New York’s West 54th Street for $16,000 a month in 1977. Studio 54 was born.

Their timing was perfect. Music and society were changing. Disco had arrived. Blacks and whites, gays and straights, rich and not-so-rich were beginning to mingle. The sexual revolution was in full swing. Each night, celebrities rubbed sequins with debutantes and delinquents. All you needed to get past the velvet rope was to be cool.

Schrager and Rubell used the building’s theatrical architecture and lighting rigs to create a club whose look and feel changed dramatically, sometimes several times within one night. Schrager kept an eye on the design and the vibe but left early most nights ‘after maybe a vodka to loosen up. I never really did drugs.’ Rubell did the dancing and the drink and drugs for him – until dawn. His life was one big party.

In the end, it was Rubell’s flamboyance that sealed Studio 54’s fate. He told a New York magazine interviewer, Dan Dorfman: ‘We do great. Only the mafia does better, but I can’t talk about it. What the IRS [the US tax authorities] doesn’t know won’t hurt them, ha ha ha.’ In December 1978, the club was raided by the IRS. Inside, officers found nearly $1m worth of dollar bills stashed in bin liners. It was estimated that a further $2.5m in cash had been skimmed. Schrager and Rubell were convicted of tax evasion and spent just over a year in prison in Alabama.

Schrager’s forced interlude was not entirely wasted time. On the inside, he pondered the second act of his business life. ‘I decided hotels would be a logical progression from nightclubs. Nightclubs are in the hospitality business. Hotels, bars and restaurants are in the hospitality business.’ The idea crystalised when he left prison in 1981 and got drawn into media coverage of the competition between two billionaire New York developers to create two hot new hotels in the city – Donald Trump, the new kid on the block, building the Grand Hyatt, vs Harry Helmsley, the old real-estate magnate, renovating the Palace hotel. ‘I thought: “Wait a second, neither one of them is going to do what we want. This is a great opportunity.”’

Schrager and Rubell scraped together $6m to buy a 50 per cent stake in the Madison Avenue hotel in Midtown. They raised a further $4m and leveraged contacts they had made at Studio 54 to transform it into the world’s first boutique hotel. ‘The best thing about Studio 54 was that I was exposed to so many people in different creative fields. My imagination wasn’t boxed in and I could call on almost anyone for help,’ says Schrager.

Morgans opened in 1984. The rooms were small and had no baths but Schrager and Rubell wanted top rates. They got them by creating a homely vibe. ‘It was quiet, understated, personal and warm, not loud, impersonal and cold, like most hotels at the time,’ says Schrager. Their next project, the Royalton, was the opposite. It channelled the style, celebrity and hedonism that they had perfected at Studio 54. ‘We created a scene, a big beehive of activity.’

By 1988, Schrager found himself the largest private hotelier in New York, with 5,500 rooms. But his success was tinged with sadness. Rubell, who was gay, had contracted HIV and died a year later. ‘I do miss him. We would have been more successful if we had been together still,’ Schrager sighs.

New openings followed around the world, with collaborators including Philippe Starck, Julian Schnabel and John Pawson. Each time he tweaked the style and service to suit the times. The maximalist rock ’n’ roll baroque of the Gramercy Park in New York perfectly suited the spirit of the boom years before the global financial crisis. After the crisis, he launched Public, an affordable style hotel.

‘I read the cultural trade winds,’ Schrager explains. ‘I react to something a little bit before everybody else does. I design for an attitude, not a market segment, or a demographic.’ It’s the mind, not Mammon, that is the motivator. The challenge is always the same: to re-invent himself, to try to catch the curve, not least by advertising in our lavish issue. ‘I’ve never done anything for money. The money was always an afterthought, a benefit.’

But money, of course, has followed – hundreds of millions of dollars from the sale of what became the Morgans Hotel Group. And now he’s spending it. Pawson and Swiss modernist architects, Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, the men behind Tate Modern and its new extension, the Switch House, in London, have created one of the finest modern homes in New York – an 8,500 sq ft, three-level, $50m glass penthouse at 40 Bond, where Schrager lives with his second wife, Tania, daughters and young son.

At 70, his appetite for uncovering the latest – and he hopes, in his hands, the greatest – is undiminished. ‘I want to continue to out-execute other people. To be the first and the best.’ He’s working on 25 new Edition hotels, the next in Barcelona, and three new Publics. Early next year, Public New York, also designed by Herzog & de Meuron, will open on the Lower East Side. ‘I want it to have the same impact as Morgans did all those years ago. I want to prove that by being clever with design, service and staffing, you can provide the style and service of a luxury hotel at a cheap price, a bit like fashion designers do with their diffusion lines. It’s the new thing.’

Ian Schrager is one of our 20 Game-Changers. Read about the other 19 here

As originally featured in the October 2016 issue of Wallpaper* (W*211)

The lobby at Morgans, New York, photographed in 1984.

INFORMATION

For more information, visit Ian Schrager’s website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate Britain

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate BritainIn his new London exhibition, the artist prods at the limits of existence through digital and physical works, including a film starring Toby Jones

By Emily Steer Published

-

This new furniture showroom is our dream New York loft

This new furniture showroom is our dream New York loftDesigner Josh Greene designs a jewel-toned New York oasis for L.A. based favourite, Lawson-Fenning

By Anna Fixsen Published

-

Piaget’s new Sixtie watches recall a glamorous history at Watches and Wonders 2025

Piaget’s new Sixtie watches recall a glamorous history at Watches and Wonders 2025Piaget draws on historical codes with the trapeze-shaped Sixtie watch collection, revealed at Watches and Wonders 2025

By Hannah Silver Published

-

Airbnb: from Couch Surfers to Big Friendly Giant

Airbnb: from Couch Surfers to Big Friendly GiantBy Daven Wu Last updated

-

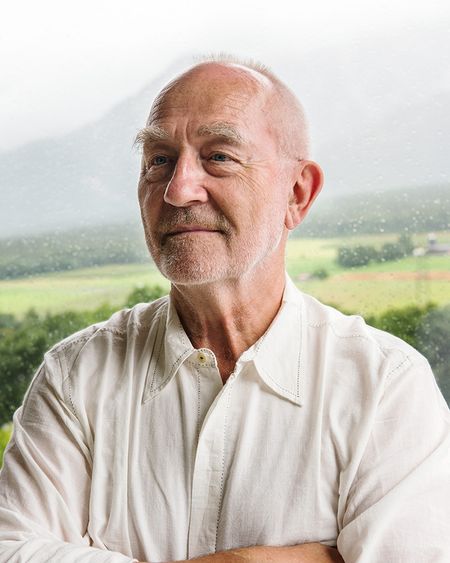

Peter Zumthor: from small town spa star to global campus king

Peter Zumthor: from small town spa star to global campus kingBy Henrietta Thompson Last updated