Becoming Bauhaus: the defining eras of Josef Albers, at Stephen Friedman

The German-born American artist Josef Albers is much celebrated for his Homage to the Square paintings, but a new exhibition at Stephen Friedman Gallery in London is bringing to light a seldom-seen chapter of his life and oeuvre. Opened this week, the show tells the story of the Bauhaus – the German revisionist school founded in 1919 by the architect Walter Gropius – through Albers’ prolific output, alongside furniture, objects, ceramics and photographs by his colleagues including Marcel Breuer, Otto Lindig and Marianne Brandt.

It’s the most substantial exhibition of Bauhaus art and design mounted by a commercial gallery – many of the pieces on show have never been exhibited in the UK before – bringing together material loaned by the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, as well as from private collections. ‘We look at Bauhaus design and assume that because the designs are so famous and were produced in greater number later that there are lots of them, which isn't the case,’ explains curator Oscar Humphries.

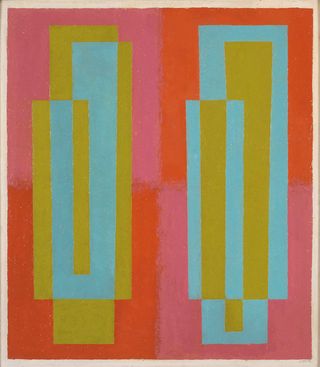

In the main gallery space, an eye-catching glass painting – City, 1935 – hung in the far corner immediately draws us in for a closer look. ‘To have an Albers glass work in the show is really special,’ says Humphries, arguing that works such as this are Albers’ most important Bauhaus-era pieces. Sadly, as is the case with so many Bauhaus designs, few examples of Albers’ glass works exist, either broken during the war or by being mishandled by US customs when he moved to America.

This particular painting was made to record a lost glasswork from a decade earlier; as with much of Albers’ work, there is more to the piece than meets the eye. ‘The painting,' Humphries explains, 'is in an Albers-designed frame and together show how much he valued – as we should – his work from the Bauhaus period.’

Elsewhere in the show, Albers’ 'Tea Glass with Saucer and Stirrer' is a wonderful sort of Duchamp-esque arrangement of found objects. The porcelain dish, for example, was originally produced by Meissen for scientific use; the only element created by Albers himself is the connecting metal and the ebony handle. ‘It's very Bauhaus to take these mass-produced elements and make another thing from it. And very Albers,’ Humphries explains of the tea glasses, which never went into production.

As pivotal as Albers was to the Bauhaus, it would be impossible to paint a full picture of the German art school without including works by his influential peers. An 18-year-old Marcel Breuer joined the Bauhaus in the very same year as Albers. The exhibition features a rare example of his 'Lattenstuhl', 1923 – actually made at the Bauhaus workshop – and rarer still, the ‘Wassily Club Chair’, 1927, which only existed in prototype form before the version on show was produced (both are courtesy of Galerie Ulrich Fiedler). The curator adds: ‘Few people bought Breuer's furniture when he first made it – it wasn't until the 1950s that taste caught up with him.’

Other highlights include a Bauhaus wallpaper sample book, a Brandt-designed inkwell and archival photographs of the school, as well as a characterful chess set by Josef Hartwig and Joost Schmidt.

In 1933, the Bauhaus bowed to mounting pressure from the newly elected Nazi government and closed. Albers went into exile in America. ‘Albers was in his 40s when he moved to the US; he could have simply taught and his contribution to the Bauhaus would have been enough to cement his place in art history books,’ says Humphries. ‘He didn't though. His best work – arguably – was ahead of him.’

Enter Annelise Fleischmann – or, as we know her now, Anni Albers. The textile artist/printmaker met Josef in 1922 at the Bauhaus, marrying him three years later. After the closure of the school and the subsequent transatlantic move they travelled frequently to Mexico and throughout the Americas. 'Mexico,' wrote an enthused Josef to Bauhaus colleague Wassily Kandinsky, 'is truly the promised land of abstract art.' Anni, meanwhile, became a keen collector of pre-Columbian art – a passion that manifested itself visually in her work.

To wit, a second room of the exhibition explores the couple’s post-Bauhaus endeavours. Nicholas Fox Weber, executive director of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, quipped, ‘How great to be discussing this exhibition with someone from Wallpaper*, because the absolute thriller in the show is the use of wallpaper.’ Here, Lucy Swift Weber – who leads the foundation’s special projects – has transformed Anni’s ‘E’ pattern into bold wallpaper in collaboration with Christopher Farr Cloth.

It’s the very first time Josef’s work, too, has been exhibited on Anni’s wall coverings. ‘Oscar Humphries papered a room with it – an act of sheer panache,' Weber adds. 'The Bauhaus joie de vivre in everyday living has been brought to life as never before nearly a century after the school was created.’ But mostly, the Stephen Friedman exhibition offers a rare and poignant example where a whole – the Bauhaus, and Mr and Mrs Albers for that matter – was equal to the sum of its truly brilliant parts.

The Bauhaus was the German revisionist school founded in 1919 by the architect Walter Gropius. Pictured: 'Albers & the Bauhaus', installation view. Photography: Mark Blower. Courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery

This is the most substantial exhibition of the movement to be mounted by a commercial gallery yet; many of the pieces have never been shown in the UK before. Pictured: 'Albers & the Bauhaus', installation view. Photography: Mark Blower. Courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery

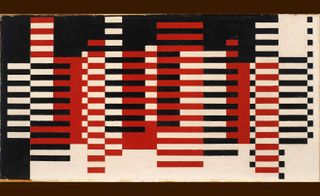

An eye-catching glass painting – Lauben (Trellis), 1929 – hung in the far corner of the main room, is a large draw of the show. ‘To have an Albers glass work in the show is really special,’ says curator Oscar Humphries. Photography: Courtesy of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation

Another particularly striking piece is City, made in 1935 to record a lost glasswork from a decade earlier. Pictured: City, by Josef Albers, 1928–36. Courtesy of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation

Albers’ 'Tea Glass with Saucer and Stirrer' (1925), pictured, is a wonderful sort of Duchamp-esque arrangement of found objects. Courtesy of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation

As pivotal as Albers was to the Bauhaus, it would be impossible to paint a full picture of the German art school without including works by his influential peers. Pictured: the ’Swivel-Arm Wall Lamp No.830’, by Heinrich-Siegfried Bormann, 1931, hangs over the Marcel Breuer-designed ’Table B14’, 1930, and Breuer’s ’Side Chair B5’, 1926–27. Photography: Mark Blower. Courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery

An 18-year-old Breuer joined the Bauhaus in the very same year as Albers. ‘Few people bought Breuer’s furniture when he first made it,’ says Humphries, ’it wasn’t until the 1950s that taste caught up with him.’ Pictured: ‘Lattenstuhl Armchair Model TI 1A’, by Marcel Breuer, 1923

‘Wassily Club Chair B3’, by Marcel Breuer, 1927

In 1933, the Bauhaus bowed to mounting pressure from the Nazis and closed. Albers went into exile in America. Pictured: a photograph of Josef and Anni Albers taken on their arrival in the US, 1933. Photography: Associated Press. Courtesy of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation

A second room of the exhibition explores the couple’s post-Bauhaus endeavours. Against a backdrop of Anni Albers-designed wallpaper are various drawings and paintings made by the couple across this period. Photography: Mark Blower. Courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery

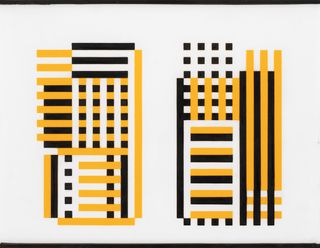

Oscillating (C), by Josef Albers, 1940–45. Courtesy of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation

Other highlights of the show include a Bauhaus wallpaper sample book, a Brandt-designed inkwell, archival photographs of the school and, pictured here, a characterful chess set by Josef Hartwig and Joost Schmidt, created in 1923–24

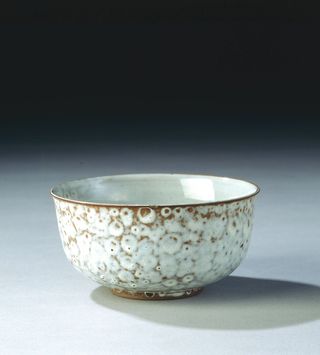

Pieces by the lauded Bauhaus ceramicist Otto Lindig are also on show. Pictured: ’Bowl’, by Otto Lindig, 1928–30

The exhibition weaves the tale of a poignant and rare example where a whole – the Bauhaus, and Mr and Mrs Albers for that matter – was equal to the sum of its truly brilliant parts. Pictured: ’Albers & the Bauhaus’, installation view. Photography: Mark Blower. Courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery

INFORMATION

'Albers & the Bauhaus’ is on view until 12 March. For more information, visit Stephen Friedman Gallery's website

ADDRESS

Stephen Friedman Gallery

Gallery Two

11 Old Burlington Street

London, W1S 3AQ

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

The Wallpaper* Design Issue comes with our Salone del Mobile must-sees

The Wallpaper* Design Issue comes with our Salone del Mobile must-seesThe May 2025 issue of Wallpaper* is on sale now, taking in Milan Design Week, the Venice Biennale, and a very stylish tea party

By Bill Prince Published

-

Aboard Gio Ponti's colourful Arlecchino train in Milan, a conversation about design with Formafantasma

Aboard Gio Ponti's colourful Arlecchino train in Milan, a conversation about design with FormafantasmaThe design duo boards Gio Ponti’s train bound for the latest Prada Frames symposium at Milan Design Week

By Laura May Todd Published

-

The ultimate high-performance earbuds, courtesy of McLaren and Bowers & Wilkins

The ultimate high-performance earbuds, courtesy of McLaren and Bowers & WilkinsThe new Bowers & Wilkins Pi8 McLaren Edition continues a decade’s worth of cross-pollination between these two tech-focused British manufacturers

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate Britain

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate BritainIn his new London exhibition, the artist prods at the limits of existence through digital and physical works, including a film starring Toby Jones

By Emily Steer Published

-

Tom Wesselmann’s 'Up Close' and the anatomy of desire

Tom Wesselmann’s 'Up Close' and the anatomy of desireIn a new exhibition currently on show at Almine Rech in London, Tom Wesselmann challenges the limits of figurative painting

By Sam Moore Published

-

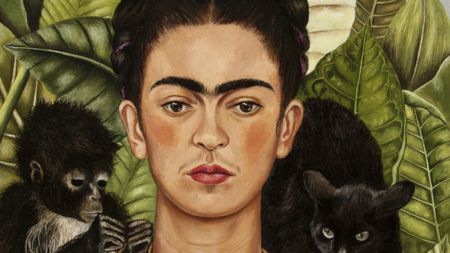

A major Frida Kahlo exhibition is coming to the Tate Modern next year

A major Frida Kahlo exhibition is coming to the Tate Modern next yearTate’s 2026 programme includes 'Frida: The Making of an Icon', which will trace the professional and personal life of countercultural figurehead Frida Kahlo

By Anna Solomon Published

-

A portrait of the artist: Sotheby’s puts Grayson Perry in the spotlight

A portrait of the artist: Sotheby’s puts Grayson Perry in the spotlightFor more than a decade, photographer Richard Ansett has made Grayson Perry his muse. Now Sotheby’s is staging a selling exhibition of their work

By Hannah Silver Published

-

From counter-culture to Northern Soul, these photos chart an intimate history of working-class Britain

From counter-culture to Northern Soul, these photos chart an intimate history of working-class Britain‘After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989 – 2024’ is at Edinburgh gallery Stills

By Tianna Williams Published

-

Celia Paul's colony of ghostly apparitions haunts Victoria Miro

Celia Paul's colony of ghostly apparitions haunts Victoria MiroEerie and elegiac new London exhibition ‘Celia Paul: Colony of Ghosts’ is on show at Victoria Miro until 17 April

By Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou Published

-

Teresa Pągowska's dreamy interpretations of the female form are in London for the first time

Teresa Pągowska's dreamy interpretations of the female form are in London for the first time‘Shadow Self’ in Thaddaeus Ropac’s 18th-century townhouse gallery in London, presents the first UK solo exhibition of Pągowska’s work

By Sofia Hallström Published

-

Sylvie Fleury's work in dialogue with Matisse makes for a provocative exploration of the female form

Sylvie Fleury's work in dialogue with Matisse makes for a provocative exploration of the female form'Drawing on Matisse, An Exhibition by Sylvie Fleury’ is on show until 2 May at Luxembourg + Co

By Hannah Silver Published