Artist Liu Bolin explores the hidden depths of champagne production at French house Ruinart

Since 2002, French champagne house Ruinart – established in 1729, and now owned by LVMH – has collaborated with a contemporary artist, tapping them to create works of art inspired by its products. Past collaborators have included Maarten Baas, Piet Hein Eek and Erwin Olaf, with Chinese artist Liu Bolin chosen for 2018. ‘We’d wanted to work with Bolin for a long time,’ says Frédéric Dufour, Ruinart’s CEO. ‘He’s an artist who stands for something.’

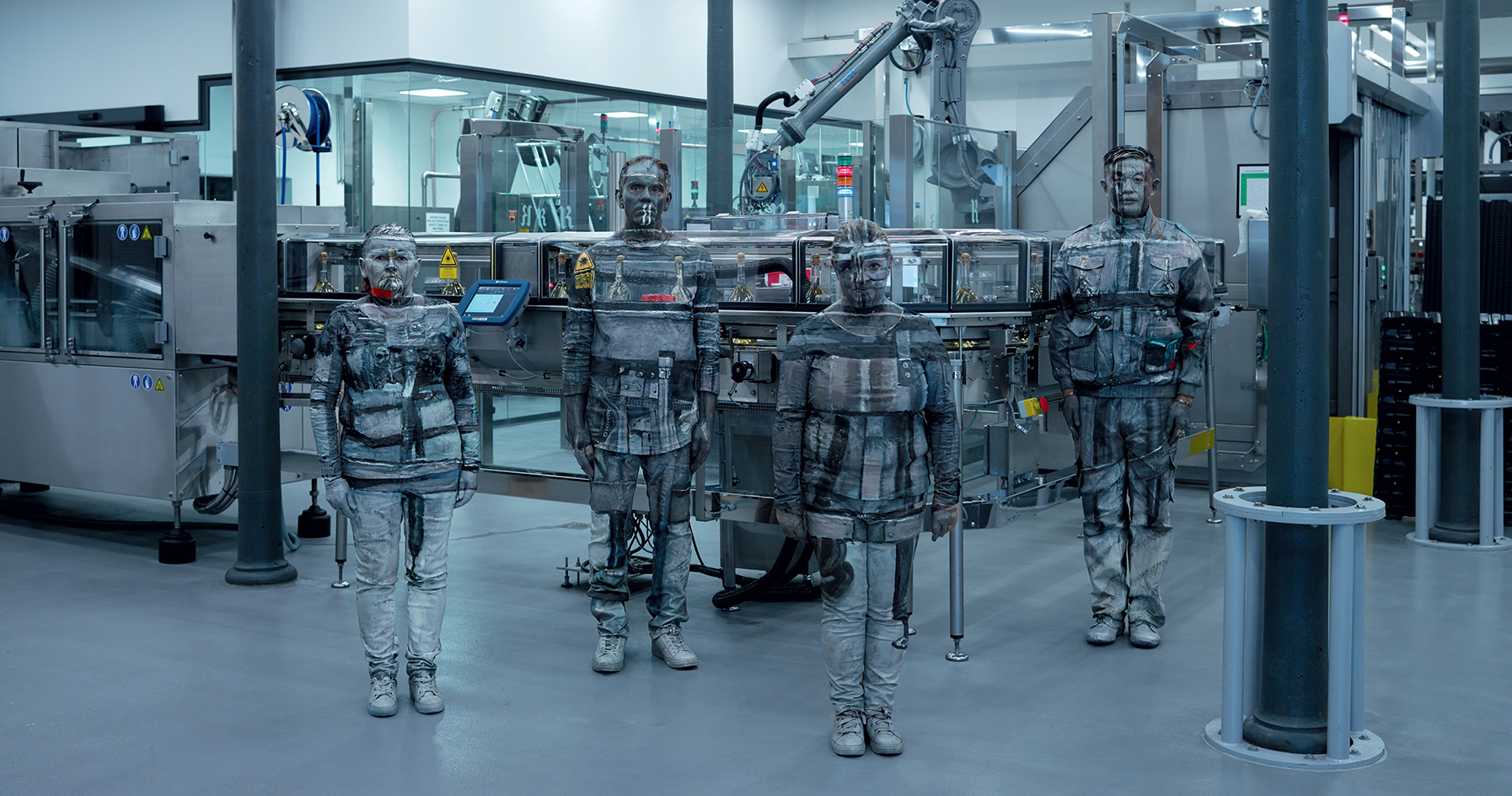

Bolin, aka ‘the invisible man’, is known for painting his body and photographing himself camouflaged against diverse backgrounds – a comment on man’s relationship to his surroundings. In August 2017, just prior to the grape harvest, he spent ten days at Ruinart, producing eight photographs of the estate and the people working there.

Artist Liu Bolin in one of Ruinart’s crayères.

Throughout the year, these works will travel to more than 30 major art fairs, including Art Basel, Frieze and FIAC. But you can also visit the scene of where it all took place, with a two-hour Ruinart tour that offers the advantage of champagne tasting.

Ruinart’s story stretches back to the 17th-century Benedictine monk Dom Thierry Ruinart, who lived in an abbey close enough to Paris to learn about a new ‘wine with bubbles’ that was driving the aristocrats wild. When he returned to his native Champagne region, he told his brother that he believed the beverage had serious potential. In 1729, Dom Ruinart’s nephew Nicolas created the world’s first champagne house and soon after, Nicolas’ son, Claude Ruinart, moved the estate to its current address in Reims with the ingenious idea of using the local crayères (chalk pits) to store the champagne. With a constant temperature of around 10°C and close to 100 per cent humidity, they provided the ideal conditions for maturation.

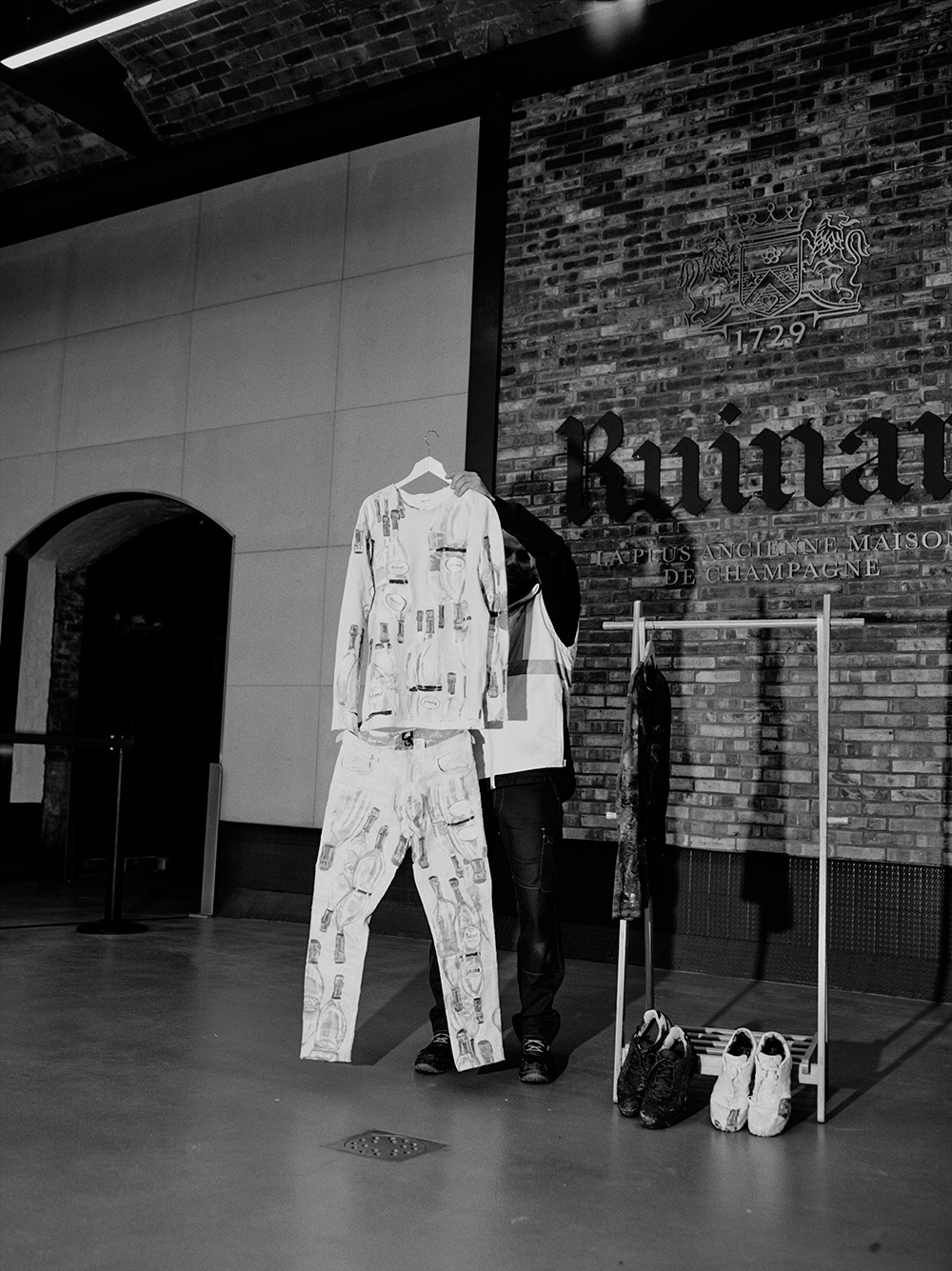

The clothing painted for Lost In Blanc De Blancs Bottles, held by Ruinart cellarmaster Frédéric Panaiotis, who also appears in the work.

The Gallo-Romans started excavating the region’s crayères two millennia ago, using the chalk to build Reims. Today, the crayères and their connecting tunnels zigzag for hundreds of miles underground. They are beautiful and mysterious, with narrow openings at the surface expanding into vast white chambers below. They have served the interests of monks, smugglers and Second World War soldiers, and their rough white walls bear religious icons, graffiti and other marks of this rich history. In 2015, Unesco classified them a World Heritage Site.

In Ruinart’s crayères, the deepest locally, several hundred thousand bottles of bubbly age slowly in the dim golden light. Last year the company decided to renovate a ‘secret’ crayère that had collapsed after the Second World War, hiring five climbers to reinforce the walls. It will now be an oenothèque where VVIPs can taste particularly old vintages.

The removal of the sediment from the neck of the bottle, a process known as disgorgement.

As well as the crayères, what moved Bolin about Ruinart was the human element in its manufacturing processes, the centuries of expertise behind the employees’ skills. ‘These people are working here, their life is here, so it was important to have them in the photographs,’ he says. To symbolise the ‘invisible’ hands behind each bottle of champagne, the artist posed with several workers – disappearing into the fields with the cellarmaster and into the disgorgement production line with three of its operators. He also posed with Pablo Lopez, one of the house’s two riddlers. Lopez practises a rare ancestral craft, ‘reading’ the champagne by hand, tilting and rotating the bottles in order to draw the sediment into the neck so that it can be removed later. In that photograph, he and Bolin are camouflaged against gyropalettes, the machines that take over once Lopez has programmed them to reproduce his gesture.

Ruinart’s previous artistic collaborations are displayed at the estate in Reims, as is the first piece the house ever commissioned, an advertisement designed in 1896 by Czech artist Alphonse Mucha. As part of his project, Bolin paid tribute to that original collaboration by painting himself into Mucha’s art nouveau poster.

And when Bolin unveiled his Ruinart photographs during a party in March 2018 at the Grand Palais in Paris, the chic, champagne-sipping crowd watched in fascination as the artist disappeared into an oversized version of Jean-François de Troy’s 1735 painting Le Déjeuner d'Huîtres (said to be the first in history to depict a bottle of champagne), only to become part of another chic, champagne-sipping party from three centuries ago.

As originally featured in the October 2018 issue of Wallpaper* (W*235)

INFORMATION

Tours of the crayères, including champagne tasting, cost €70 per person. To book, visit the Ruinart website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

Why champagne pairs beautifully with fine food

Why champagne pairs beautifully with fine foodMaison Krug unites champagne with decadent cuisine in the latest edition of its ‘Single Ingredient’ adventure, in collaboration with globally renowned Michelin-starred chefs who enhance the flavours and aromas of Krug Grande Cuvée or Krug Rosé

By Melina Keays

-

Taste the trilogy of Moët & Chandon Grand Vintage Champagnes

Taste the trilogy of Moët & Chandon Grand Vintage ChampagnesMoët & Chandon presents ’A Tale of Sublimation’, a trilogy of Grand Vintage Champagnes which represents the journey of harvesting and growing of the grapes, and the declaration of vintage status

By Melina Keays

-

Tuck into Ruinart and Silo’s new zero-waste supper series in London

Tuck into Ruinart and Silo’s new zero-waste supper series in LondonThe Ruinart x Silo: Savoir (Re)Faire Supper Series sees the champagne house partner with the zero-waste restaurant, and centres on the new Ruinart Blanc Singulier cuvée

By Tianna Williams

-

Toklas’ own-label wine is a synergy of art, taste and ‘elevated simplicity’

Toklas’ own-label wine is a synergy of art, taste and ‘elevated simplicity’Toklas, a London restaurant and bakery, have added another string to its bow ( and menu) with a trio of cuvées with limited-edition designs

By Tianna Williams

-

Why Bollinger’s La Grande Année 2015 champagne is worth celebrating

Why Bollinger’s La Grande Année 2015 champagne is worth celebratingChampagne Bollinger unveils La Grande Année 2015 and La Grande Année Rosé 2015, two outstanding cuvées from an exceptional year in wine-making

By Melina Keays

-

Champagne Telmont’s ‘193,000 shades of green’ bottles are a quest for sustainability

Champagne Telmont’s ‘193,000 shades of green’ bottles are a quest for sustainabilityChampagne Telmont launches ‘193,000 shades of green’, a collection of uniquely coloured bottles using otherwise unwanted glass

By Tianna Williams

-

Château Galoupet is teaching the world how to drink more responsibly

Château Galoupet is teaching the world how to drink more responsiblyFrom reviving an endangered Provençal ecosystem to revisiting wine packaging, Château Galoupet aims to transform winemaking from terroir to bottle

By Mary Cleary

-

London’s most refreshing summer cocktail destinations

London’s most refreshing summer cocktail destinationsCool down in the sweltering city with a visit to London’s summer cocktail destinations

By Mary Cleary