Special brew: ‘Rising Sun’ tea cart, by Isabelle Stanislas and Mauviel

The traditional Japanese tea ceremony is perhaps the ultimate expression of slow living, where the process of preparation becomes a meditative part of the experience. It may not be religious per se, but it is ritualistic, pivoting on the quality and detail of the objects employed and the performance of making and consumption.

With this year’s Handmade theme exploring the sacred and ceremonial, we couldn’t ignore the tea ceremony and its Japanese roots. Taking inspiration from the tools of a typical ceremony, in particular the furo, a portable iron or clay brazier used to heat water, and combining it with the conveniences of the western hostess trolley (an entertaining essential of the 1970s), we imagined a new piece of kit that could store and deliver the tea-making tools, as well as heat the water.

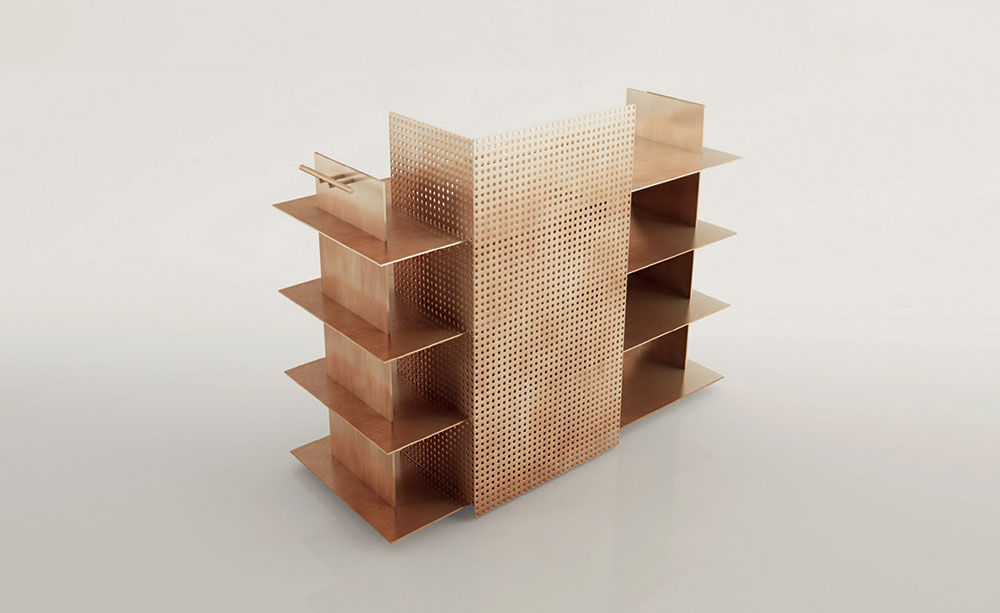

Isabelle Stanislas’ original concept for the ‘Rising Sun’ tea cart

While lacquered woods, clay and iron might be more commonly used materials in the traditional ceremony, we decided to turn to the metal of the moment, copper, and enlist the help of Mauviel, a French manufacturer with a long history of designing kitchen apparatus. Since 1830, Mauviel has created cookware beloved of both domestic cooks and world-renowned chefs. Starting its life in a Norman village known as ‘the city of copper’, the company uses knowledge garnered from generations of coppersmiths to create products of unrivalled quality and elegant design.

The now dying arts practised by some 80 workers are something Mauviel is committed to preserving. ‘Some jobs are very technical and need more than a year’s training,’ says Valérie Le Guern-Gilbert, the company’s president and member of the founding family. ‘Mauviel is the last ever “tinsmith”. It is the tinsmith of the Élysée [the presidential residence in Paris] – no one elsewhere can do what we do, so if we lose those skills, the know-how will die also.’ Le Guern-Gilbert is planning to open a dedicated school later this year, with the aim of safeguarding this heritage. ‘A tinsmith needs to be trained for 12 months, the same for martelage [a hammering technique]. Utensil crafting needs 12 months’ to two years’ training,’ she explains.

A coppersmith hammering at a weld to make it less visible

In recent years Mauviel has started to look forward, and combine tradition with contemporary design. It has teamed up with ECAL’s Masters of Advanced Studies in Design last year; has an ongoing partnership with Paris’ REV Architecture that involves product creation (see the Transformer kitchen design) and the renovation of the factory site in Normandy; and works with avant-garde chefs such as Jean-François Piège on new tools for contemporary cooking methods. ‘Our aim today is to challenge ourselves creatively. We are now creating many tailormade pieces for chefs and architects,’ says Le Guern-Gilbert, who didn’t hesitate to accept our proposal.

To realise our tea cart we chose to pair Mauviel with the Paris-based interior architect Isabelle Stanislas. Stanislas launched her agency So-An, Japanese for ‘design and composition’, in 2003. With So-An, Stanislas uses her eye for minimal compositions, a palette of natural colours, and a careful consideration of light to create refined spaces that unite past styles with contemporary tastes. ‘I found the proposal really interesting,’ she says. ‘I am fascinated by Japan, its traditions, its elegance.’ Researching the subject, she focused her attention on proportions, since the ceremony is something that takes place at floor level. ‘It was a challenge in that a tea cart is not really a piece of furniture. It is an object of contemplation that we use for a very precise moment. I loved this idea.’ Her design became a blend between a functioning cart and an object. ‘Importantly, it had to have a strong aesthetic quality, and represent my architectural style, which is to say, have elements of geometry that are both rigorous and soft at the same time.’

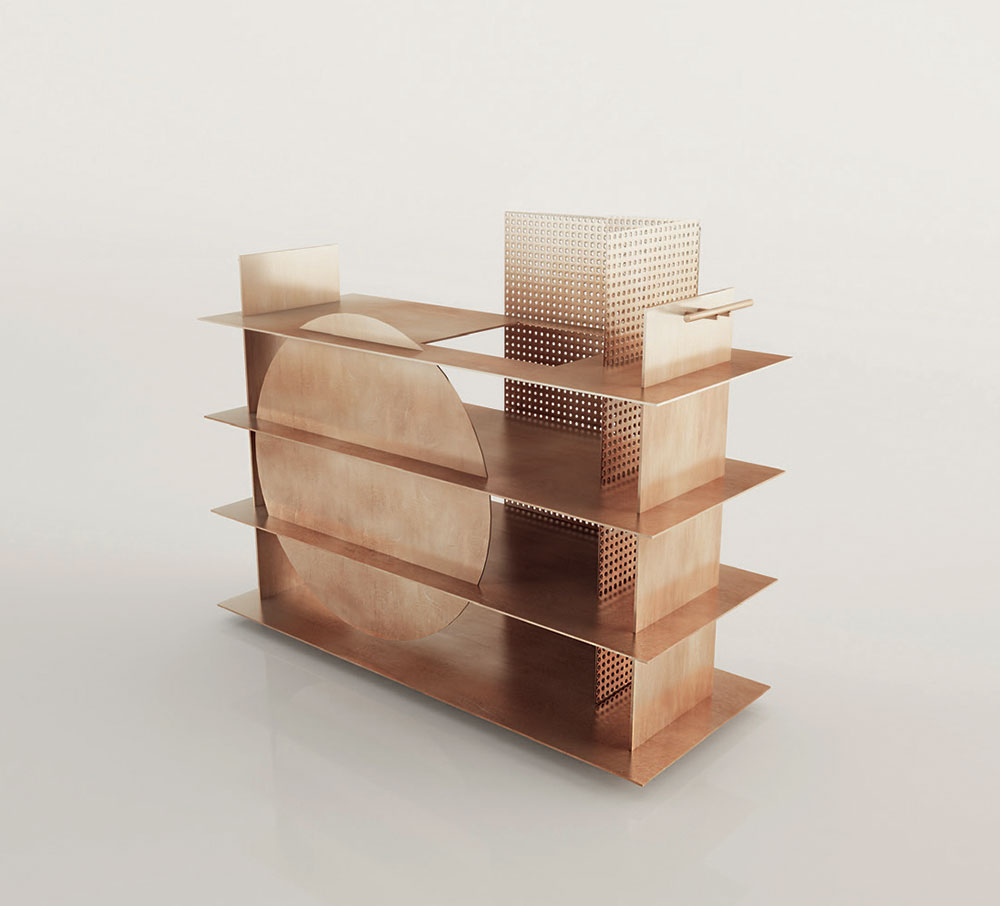

The perforated panels were replaced with mirrored steel metal sheets during the production process

With limited time to complete the project, there was daily communication over three weeks between Stanislas and her team and Mauviel and the designated artisan, and as is the way with all such projects, a degree of adaptation had to be expected, to take technical constraints into account. ‘Every material has a degree of resistance,’ says Stanislas. In the original drawings one panel was perforated, which gave it a more transparent presence, but presented a challenge to the makers. So the solution was to change the material to a mirrored steel surface, which preserved the element of transparency. The furo element was adapted from existing pieces in the Mauviel collection, but should the demand be there, a custom heater might be made to fit the cart. A true collaborative effort, the cart is a unique piece, in design, execution and function, with the possibility of adapting to diverse situations. It’s ticking all our Handmade boxes.

As originally featured in the August 2017 issue of Wallpaper* (W*221)

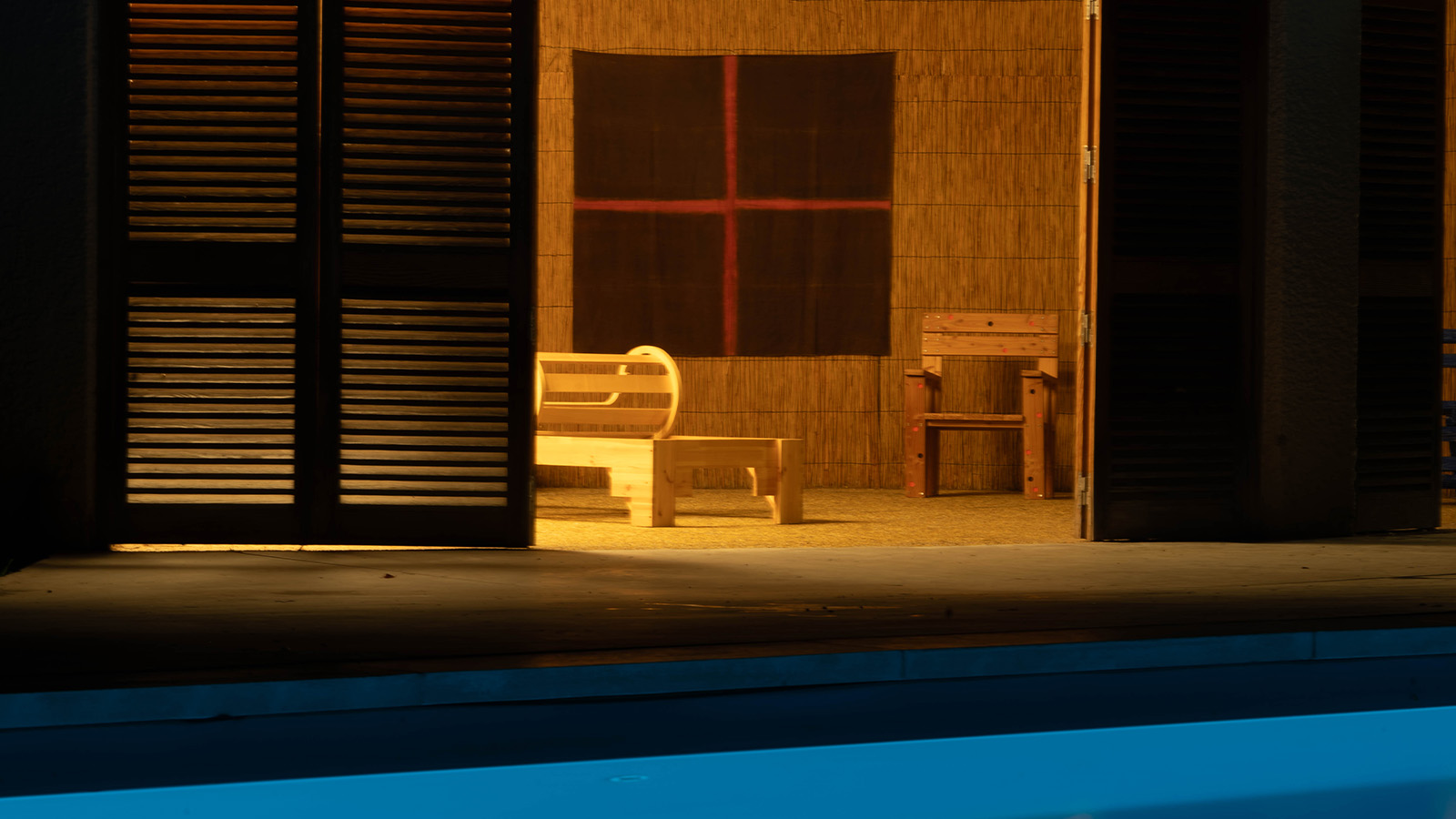

Mauviel’s factory, where a team of over 80 craftsmen produces copper cookware and restores older models

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Isabella Stanislas website and Mauviel website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Conie Vallese and Super Yaya’s beribboned bronze furniture is dressed to impress

Conie Vallese and Super Yaya’s beribboned bronze furniture is dressed to impressTucked away on the top floor of Villa Bagatti during Milan Design Week 2025, artist Conie Vallese and fashion designer Rym Beydoun of Super Yaya unveiled bronze furniture pieces, softened with hand-dyed ribbons in pastel hues

By Ali Morris

-

Contemporary artist collective Poush takes over Château La Coste

Contemporary artist collective Poush takes over Château La CosteMembers of Poush have created 160 works, set in and around the grounds of Château La Coste – the art, architecture and wine estate in Provence

By Amy Serafin

-

Sun-soaked European destinations to visit in spring

Sun-soaked European destinations to visit in springDreaming of Florentine palazzos and Greek islands now that the weather is starting to turn? Check into one of these beautiful European hotels and holiday homes

By Anna Solomon

-

The original Ligne Roset factory has been transformed into an exhibition space

The original Ligne Roset factory has been transformed into an exhibition spaceRe-christened Studio 1860, the factory was bought by the founder of the French furniture brand in 1892, and will now house rare Ligne Roset pieces, among other uses

By Anna Solomon

-

AAU Anastas and Tomoko Sauvage create a symphony of glass and sound at Ruinart's domain in Reims

AAU Anastas and Tomoko Sauvage create a symphony of glass and sound at Ruinart's domain in ReimsWallpaper* speaks to Palestinian architects AAU Anastas about their glass and sound installation at Ruinart and looks back on a pivotal year

By Ali Morris

-

Formafantasma’s biodiversity-boosting installation in a Perrier Jouët vineyard is cross-pollination at its best

Formafantasma’s biodiversity-boosting installation in a Perrier Jouët vineyard is cross-pollination at its bestFormafantasma and Perrier Jouët unveil the first project in their ‘Cohabitare’ initiative, ‘not only a work of art but also a contribution to the ecosystem’

By Henrietta Thompson

-

First look: ‘Christofle, A Brilliant Story’ is a glittering celebration of silver across two centuries

First look: ‘Christofle, A Brilliant Story’ is a glittering celebration of silver across two centuriesA landmark Christofle exhibition opens today at Paris’ Musées Des Arts Décoratifs and is the first monographic show dedicated to French silverware house

By Minako Norimatsu

-

Mosaic Factory and Zyva Studio’s new furniture collection is inspired by cartoons

Mosaic Factory and Zyva Studio’s new furniture collection is inspired by cartoonsThe Mosaic Factory x Zyva furniture collection is an ode to cartoons and the 1980s, its terrazzo tiles’ confetti-like detail nodding to the Memphis design movement

By Dominic Lutyens

-

A new exhibition looks at preparing for a post-apocalyptic landscape (and other catastrophes)

A new exhibition looks at preparing for a post-apocalyptic landscape (and other catastrophes)‘We Will Survive' at Mudac in Lausanne, introduces us to the ‘prepper movement’, and demonstrates that we are a resilient species. Or we are doing our utmost to be as prepared as is humanly possible for disasters of all scales

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Boffi and Zaha Hadid Design’s new Cove Kitchen, an Italian island dream

Boffi and Zaha Hadid Design’s new Cove Kitchen, an Italian island dreamThe newly updated Cove Kitchen is conceived as a modular hub of creation and conviviality

By Simon Mills

-

Politics, oil crises and abortion rights infiltrate the optimistic 1970s interiors of Villa Benkemoun

Politics, oil crises and abortion rights infiltrate the optimistic 1970s interiors of Villa BenkemounFor the 50th anniversary of Villa Benkemoun in Arles, a new exhibition critically explores the year of 1974 through contemporary and historic artworks that antagonise the optimism of its design

By Harriet Thorpe