Can synthetic biology solve the world’s problems?

Faber Futures, the pioneering London-based studio founded by Natsai Audrey Chieza, doesn’t just think about new approaches to form and material, but rather how to reshape the world of things from the ground up

We are a society consumed by consumption, driven to preserve the economic status quo at all costs. Natsai Audrey Chieza and her studio Faber Futures are advocates for a different approach. As designers, researchers, strategists and storytellers, Faber Futures believes design has the power to make things better. And not just by making things, but by helping restructure our social and economic systems from the ground up.

Natsai Audrey Chieza and Faber Futures

Natsai Audrey Chieza.

Born in Harare in Zimbabwe, Chieza arrived in the UK at the age of 17. After studying architecture at the University of Edinburgh, she took an MA in Material Futures at Central Saint Martins before setting up Faber Futures in London in 2018. The studio, including lead strategist Laura Emily Vent, art director Camille Thiéry, design lead Ioana Man and design researcher Magdalena Obmalko, are uniquely placed to reshape the conversation in a world screaming for change.

‘When I started the company, it was just me and I was working with a single client, a synthetic biology start-up,’ Chieza recalls. ‘I was very much focused on trying to help them think about sustainability. If you can design and programme living cells to have specific functions, then of course that’s a really interesting technology. What matters more is what you are going to do with it.’

Faber Futures arose out of this desire to shepherd new technologies into the world without inadvertently replicating or reinforcing archaic systems and structures. ‘We began in the cultural sector, in institutions like galleries and museums, where we could be provocative about future materials and technologies,’ she explains. ‘I think where we are now is moving beyond the provocation, because society is shifting its expectations about the future, and how we manage our resources with climate change.’

‘If you can design and programme living cells to have specific functions, then that’s an interesting technology, but what matters more is what you are going to do with it'

It’s not just a social shift; financial institutions are waking up to the challenges. ‘We’re entering what we like to call in the studio a “doing space”, going beyond the speculation, beyond the strategising. Now is the time to actually implement these ideas in a very tangible way.’

Designing to shape a more equitable future

Innovation does not necessarily go hand in hand with a wholesale reappraisal of the systems that govern, guide and stimulate our consumption-driven lives. One of the transparently obvious joys of technology is a constant expectation of novelty and improvement as things get faster, smaller, sleeker, cheaper, shinier, cleverer. This system works just fine if you’re at the top of the tree and can’t see – or don’t care about – the detritus and waste tumbling down to the ground to rot. To continue the metaphor, this rot is finally and undeniably affecting the roots. Climate change is coming and many current practices, from making and shipping to buying and discarding, are no longer sustainable in their current form.

Faber Futures’ work is twofold. Not only is the studio involved with the business of ‘engineering microbes to do industrially useful things’, says Chieza, but it also wants to ‘build new models and institutions that are ahead of the game and mitigating against inequity’. This approach begins by challenging preconceptions. ‘If we want to shape future markets for products derived from biotechnologies, we need to start that work now, because in ten years’ time, these technologies are going to start coming into their own. We are priming for a time where things can be implemented at scale and have a much broader impact.’

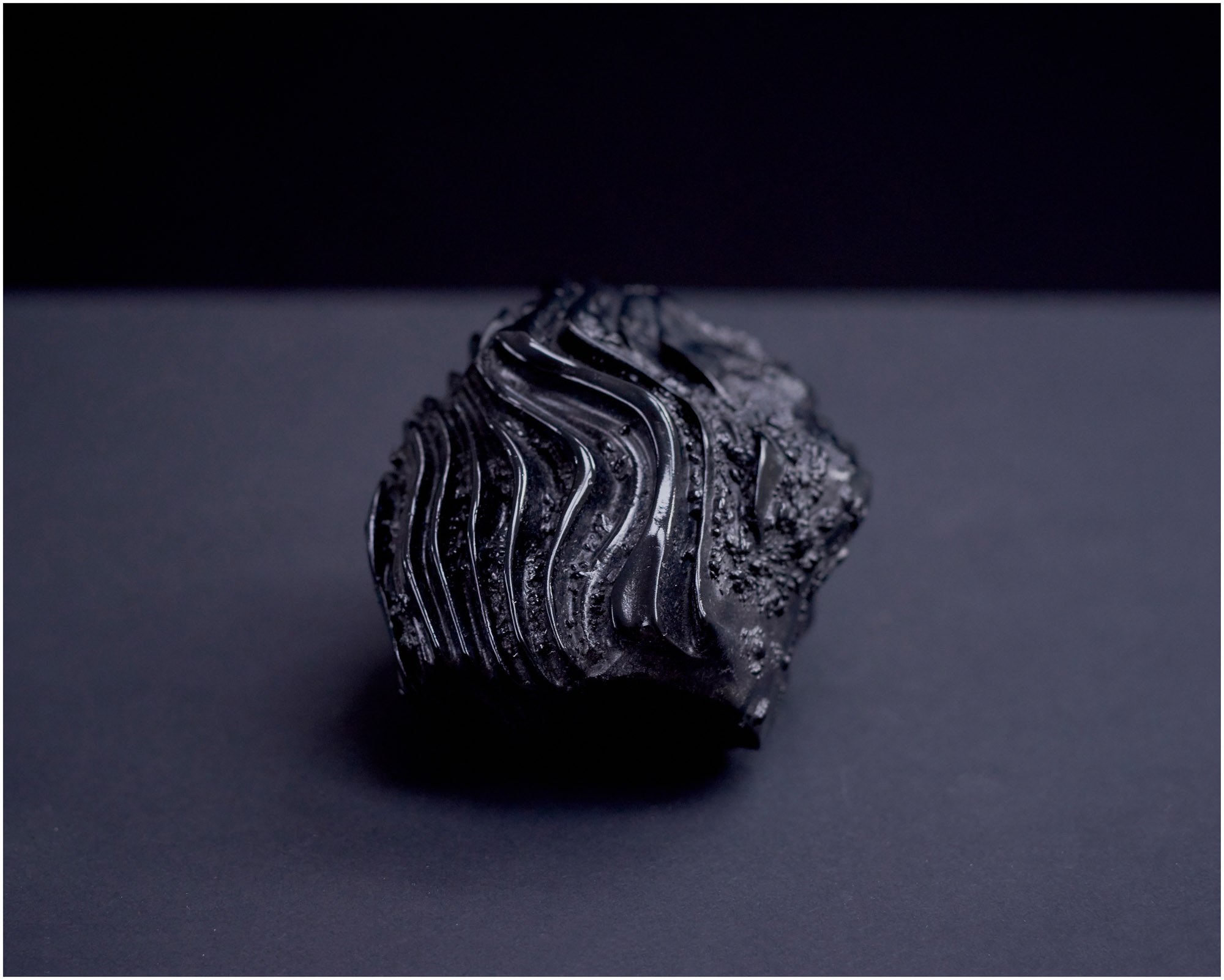

A pigment specimen extracted from Streptomyces coelicolour that contains a DNA-encrypted label of the project’s meta data. Donated to the Forbes Pigment Collection’s permanent collection at Harvard Art Museums. Faber Futures x Ginkgo Bioworks, 2018.

Back in 2017, even as Chieza was urging her TED Talks audience to consider whether biology could really ‘fix’ the fashion industry’s pollution problem, the underlying message was the same: more equitable futures could only come out of new design frameworks. ‘I’m on the Global Future Council on Synthetic Biology at the World Economic Forum, and our remit is to outline the future of synthetic biology,’ she says. ‘We’re asking a fundamental question, which is, what if SynBio was based on principles of humility, solidarity, sustainability and equity? The Council is made up of a whole host of different people from leadership to academia. Faber Futures is coming in and saying that, actually, the cultural sector has a huge role to play in connecting what is on the molecular scale with the real world.’

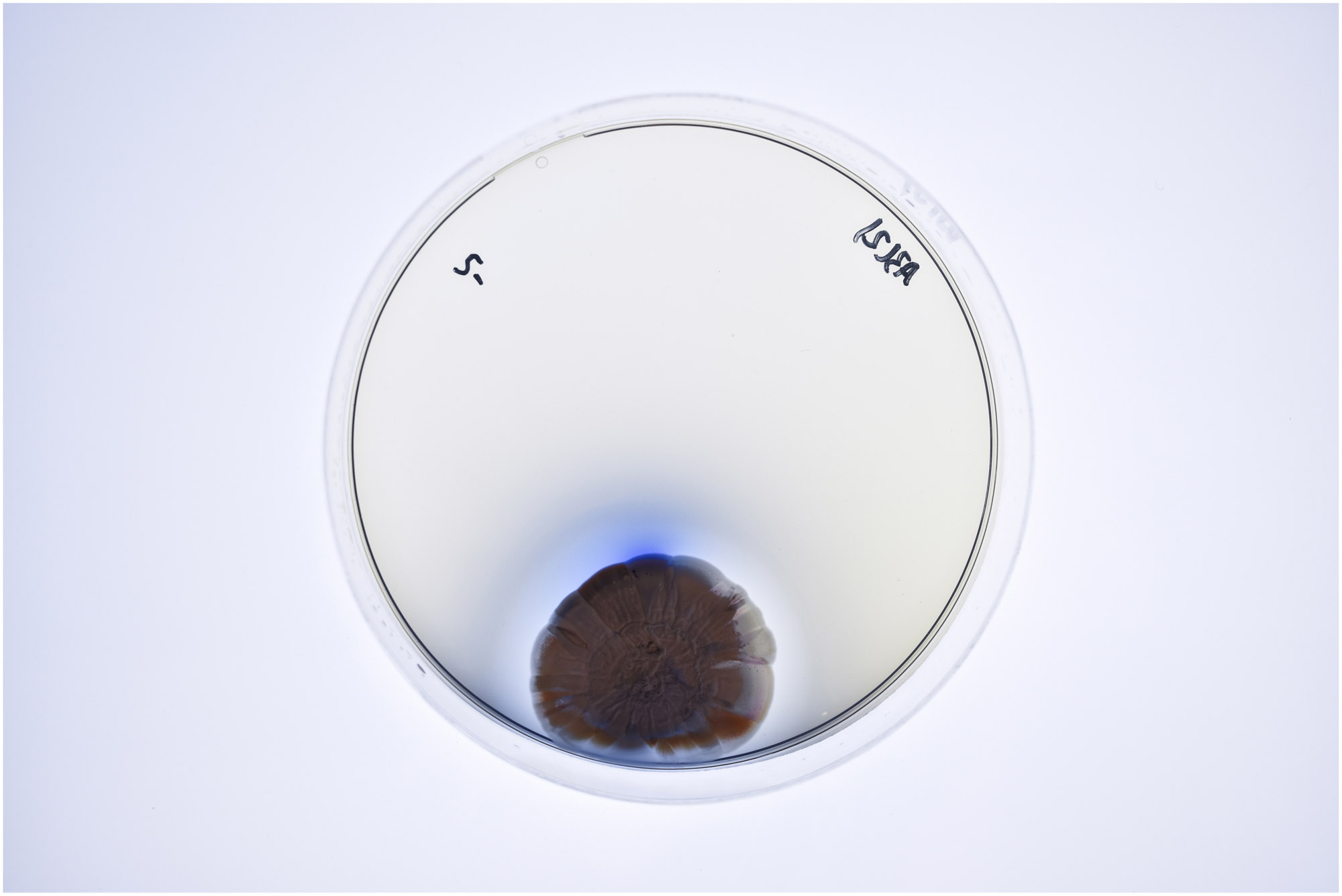

The conflict and contradiction occur when these innovations simply perpetuate existing power dynamics and economic structures. For example, fast fashion. Faber Futures’ Project Coelicolor is a case in point. Starting with a wild strain of Streptomyces coelicolor, a soil-dwelling bacteria used in antibiotic production, the studio worked with Professor John Ward at the University College London’s department of biochemical engineering to explore whether the blue pigment it naturally secreted could be used as a textile dye. Ultimately, a colourfast finish was achieved without using excess water or industrial chemicals. Could such a ‘product’ be brought to the high street? It’s a challenge Faber Futures sets out to address. ‘Project Coelicolor has been in thoughtful development for the last ten years through cultural institutions, which is a really slow process,’ says Chieza. ‘If we shifted up a gear and moved beyond exhibition pieces that communicate the potential – very richly – and try to actually make it exist, what does the work become? What kind of start-up model could emerge from R&D with this legacy?’

New systems for creative leadership

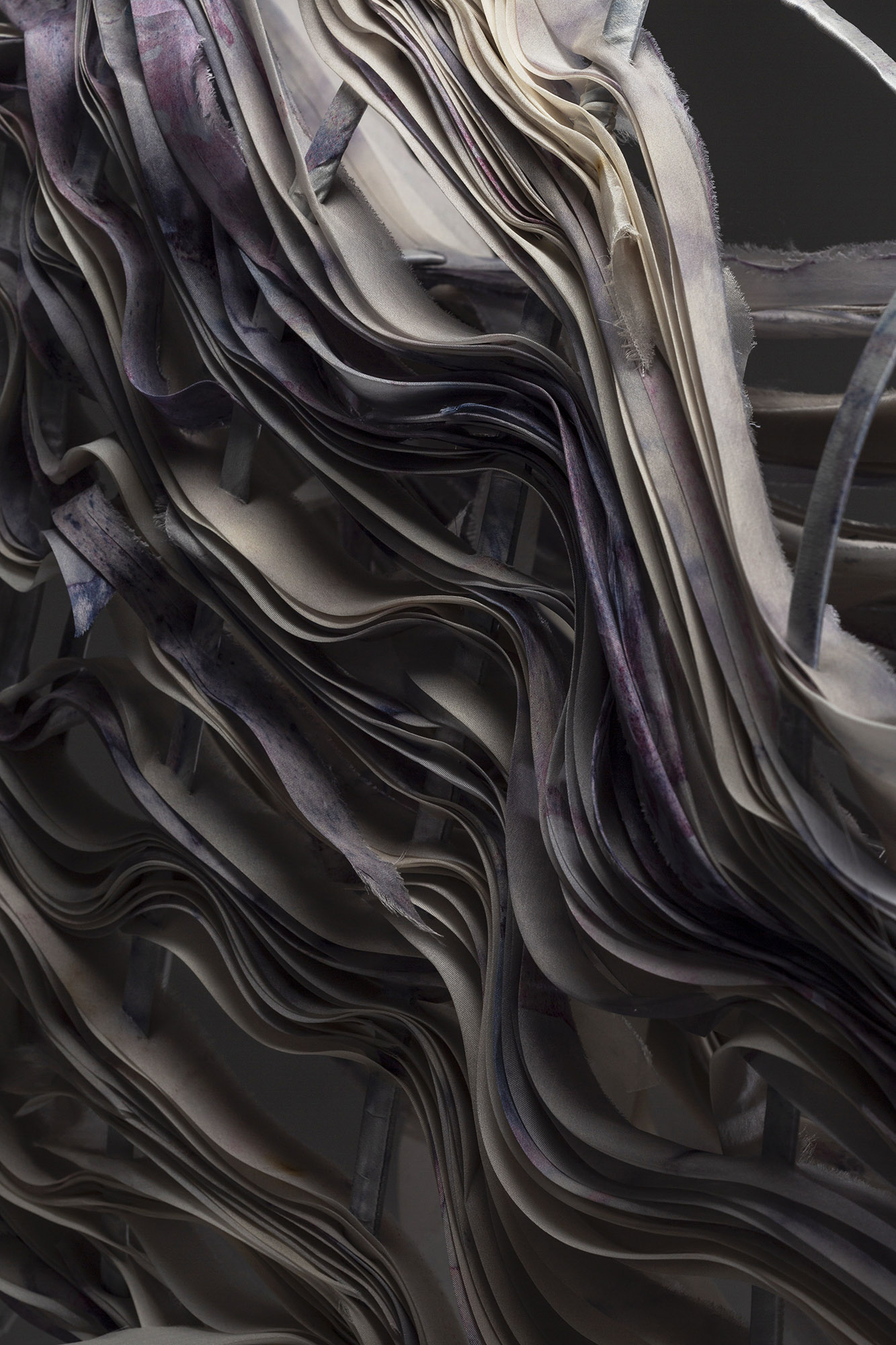

From Project Coelicolor, ‘Assemblage 002’, a bacteria-dyed reversible silk coat created by Faber Futures in collaboration with Professor John Ward, Department of Biochemical Engineering, University College London, and commissioned by Cooper Hewitt Museum, 2019.

Chieza is pragmatic and practical. ‘We need to tone down the rhetoric that this is world-changing or revolutionary, because actually it isn’t.’ Most importantly, the gains made by SynBio and other biotechnologies will be blunted if they are just absorbed into existing systems. ‘You can engineer a yeast cell, for example, to produce a very specific commodity compound,’ she says. ‘We know how to ferment on an industrial scale – just look at beer. There are infrastructures and industries and brands who do just that. But the question we’re asking is, are those brands, companies and infrastructures fit for a world that is being changed by climate change? If the answer to that question is no, then perhaps just changing a single ingredient is not enough for us to see the change that we need.’

She cites another example. ‘It would be nice to clean up fast fashion’s supply chain. But the paradox is that their business model is based on consumption and infinite growth; it is totally unsustainable.’ Project Coelicolor could be brought to bear on the chemical-and water-intensive process of dyeing and yet, ultimately, all it would do is ‘shift the raw material from petroleum to sugar, if deeper systemic issues are left unaddressed’.

‘Transversal’ sculpture featuring Streptomyces coelicolor on silk. By Faber Futures in collaboration with Professor John Ward, Department of Biochemical Engineering, University College London, 2019.

So how can all these things be tackled? One answer is education. ‘We need designers who are capable of thinking and designing within very complex systems,’ says Chieza. ‘So what kind of education system is required for that? There is a pipeline for science PhDs to become start-up founders, but I also want to see these start-up founders coming out of more diverse institutions, such as Central Saint Martins. We need leadership from the creative sector.’ Chieza argues that designers have to think in a more entrepreneurial way.

Of course, there are also philosophical and moral issues at play. ‘How do you engage with something that culturally, in the most part, you’re trying to challenge? We have to engage with the system on some level.’ One of Faber Futures’ clarion calls is to elevate the arts and humanities to the same level of political importance as STEM subjects. ‘Including the design and creative industries within STEM is not a panacea, but it is currently missing in a fundamental way.’

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The problem with design

Textiles being dyed with the bacterial pigment. Faber Futures x Ginkgo Bioworks, 2017

Above all, Chieza and her team believe that designers can and should expand their scope. In the modern era, ‘design’ has become culturally fixed as a commodity as opposed to a process. ‘If I think of my identity as a designer, it’s always been really difficult because I don’t make “stuff”, so I don’t often get featured in magazines that like to talk about stuff, she says. ‘Instead, I tend to speak to people who are interested in process and systems. Yet design has caused so many of the problems that we now face. The industry is slow to admit it and is waiting for someone else to figure it out.’ Chieza gives the example of big manufacturers who talk the talk yet wait for innovation to come their way. Instead, she says, they should be proactive and contribute their supply chain and manufacturing knowledge, helping, for example, the process of creating alternatives to leather, different dyeing processes or better recycling outcomes.

‘We have quite “sector agnostic” clients,’ she says, with a hint of frustration. ‘You would think that the design industry would be clamouring to cross-pollinate and work with scientific researchers and technologists, but they’re not. They’re just waiting.’

Likewise, as consumers, we are content to exist in a cycle of constant upgrades. We are kept supine by option paralysis, a situation that suits the status quo. ‘So far, we’ve only looked at sustainability through the lens of a society that is primed to be a consumer society and a consumer economy,’ says Chieza. ‘Our society is about trading commodities. But we have to look deeper. The question of sustainability is also about how we structure our global economies and supply chains, and whether or not resources are distributed equitably. Not just for consumers but for producers. Just providing the molecule that replaces toxic dyes is not going to be enough.’

Insert ‘You would think that the design industry would be clamouring to cross-pollinate and work with scientific researchers and technologists, but they’re not. They’re just waiting.’quote here

Faber Futures is talking about change on a molecular level and change on a society-wide level at the same time; fashion is simply a good place to start. Yet although we’re on the cusp of a biotechnological revolution, its potential could still be squandered if there aren’t radical shifts in the making, shipping, buying and disposing of goods. ‘Sustainable means lots of things, including how innovation and infrastructure have to be connected to jobs or marginalised communities,’ Chieza stresses. ‘These projects are not about product for product’s sake, but are a vehicle for different kinds of social and economic organisation. After all, what’s the point of having a bottom line for your shareholders if there’s no planet?’

INFORMATION

This article appears in the August 2021 issue of Wallpaper* (W*268), on newsstands and available for free download

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.

-

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial site

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial siteWe tour the Xingfa cement factory in China, where a redesign by landscape specialist SWA Group completely transforms an old industrial site into a lush park

By Daven Wu

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

We feel a growing passion for MycoWorks, the company inspiring beauty with fungal-based biomaterial

We feel a growing passion for MycoWorks, the company inspiring beauty with fungal-based biomaterialReishi is a Wallpaper* Design Award winner, a new self-growing, biodegradable material by MycoWorks presented in a series of exquisite expressions of earthy and ethereal furniture, lighting and artworks

By Hugo Macdonald

-

This new all-natural sofa is made with cork leftover from the production of wine stoppers

This new all-natural sofa is made with cork leftover from the production of wine stoppersIsomi’s ‘Tejo’ sofa is constructed entirely of natural materials and features a modular, experimental design

By Tianna Williams

-

New Mater tables by Patricia Urquiola are made from recycled coffee beans

New Mater tables by Patricia Urquiola are made from recycled coffee beansThe Alder collection of tables by Patricia Urquiola for Mater make their debut at Milan Design Week 2024, and are made of a specially-developed material made from recycled coffee beans

By Rosa Bertoli

-

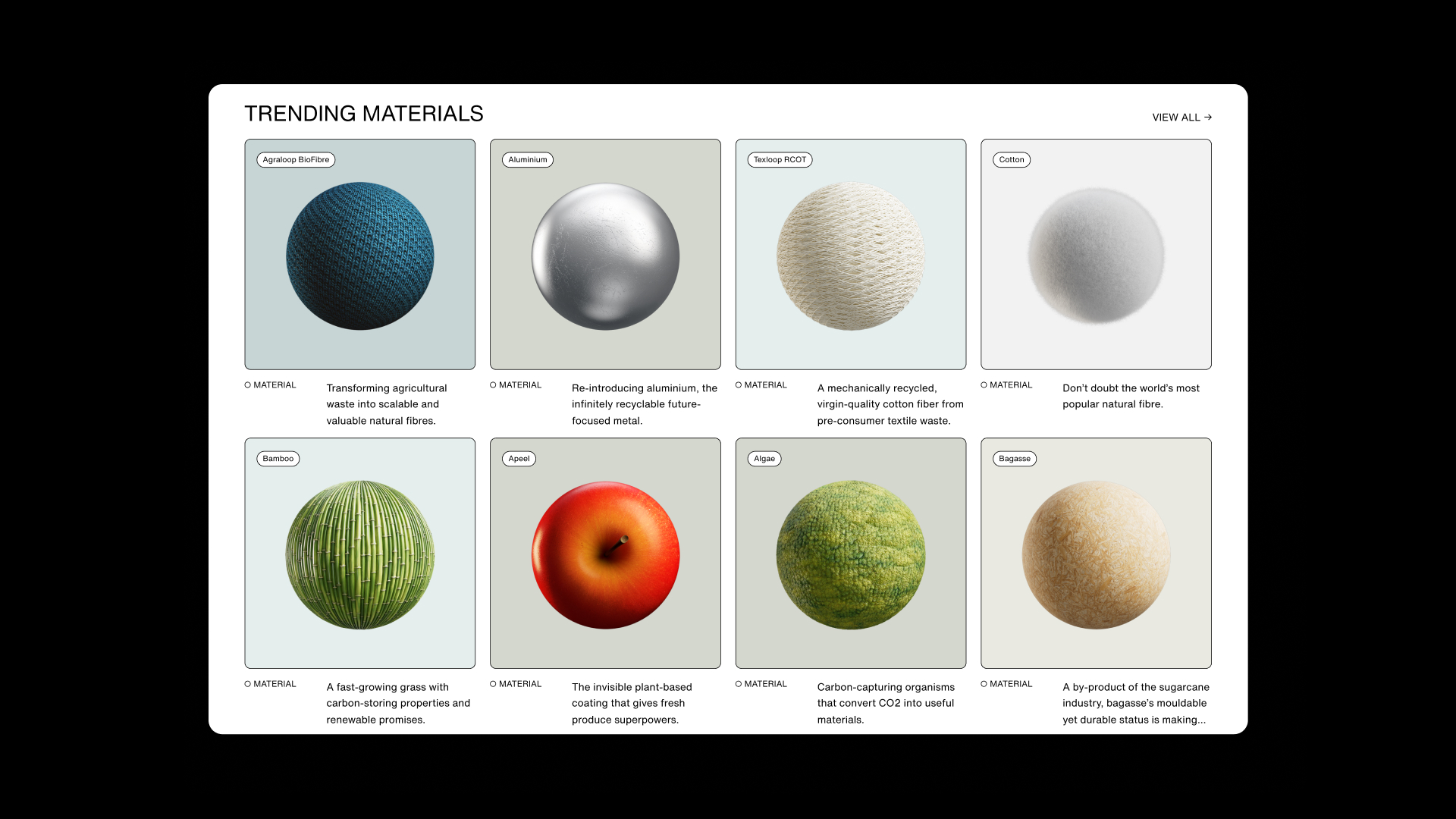

Discover Plastic Free: the new online destination for alternative materials

Discover Plastic Free: the new online destination for alternative materialsPlastic Free is a new portal for creatives looking to explore alternatives to plastic in their work

By Rosa Bertoli

-

Shellmet: the helmet made from waste scallop shells

Shellmet: the helmet made from waste scallop shellsShellmet is a new helmet design by TBWA\Hakuhodo’s creative team and Osaka-based Koushi Chemical Industry Co, made using Hokkaido’s discarded scallop shells

By Jens H Jensen

-

Wentz presents innovative furniture incorporating ocean plastic waste

Wentz presents innovative furniture incorporating ocean plastic wasteThe ‘Mar’ collection by Guilherme Wentz is informed by the sea and features computerised 3D-weaving techniques to transform ocean-borne plastic

By Scott Mitchem

-

Liaigre ‘Upcrafted’ objects showcase potential of sustainable design

Liaigre ‘Upcrafted’ objects showcase potential of sustainable designStriding confidently towards more sustainable production, interior design company Liaigre has released ‘Upcrafted’, a series of limited-edition objects for the home, assembled attentively from the studio’s would-be waste

By Martha Elliott

-

Regenerative design: meet the creatives taking a rooting interest in learning from nature

Regenerative design: meet the creatives taking a rooting interest in learning from natureRegenerative design: meet the creatives taking a rooting interest in learning from nature

By Malaika Byng