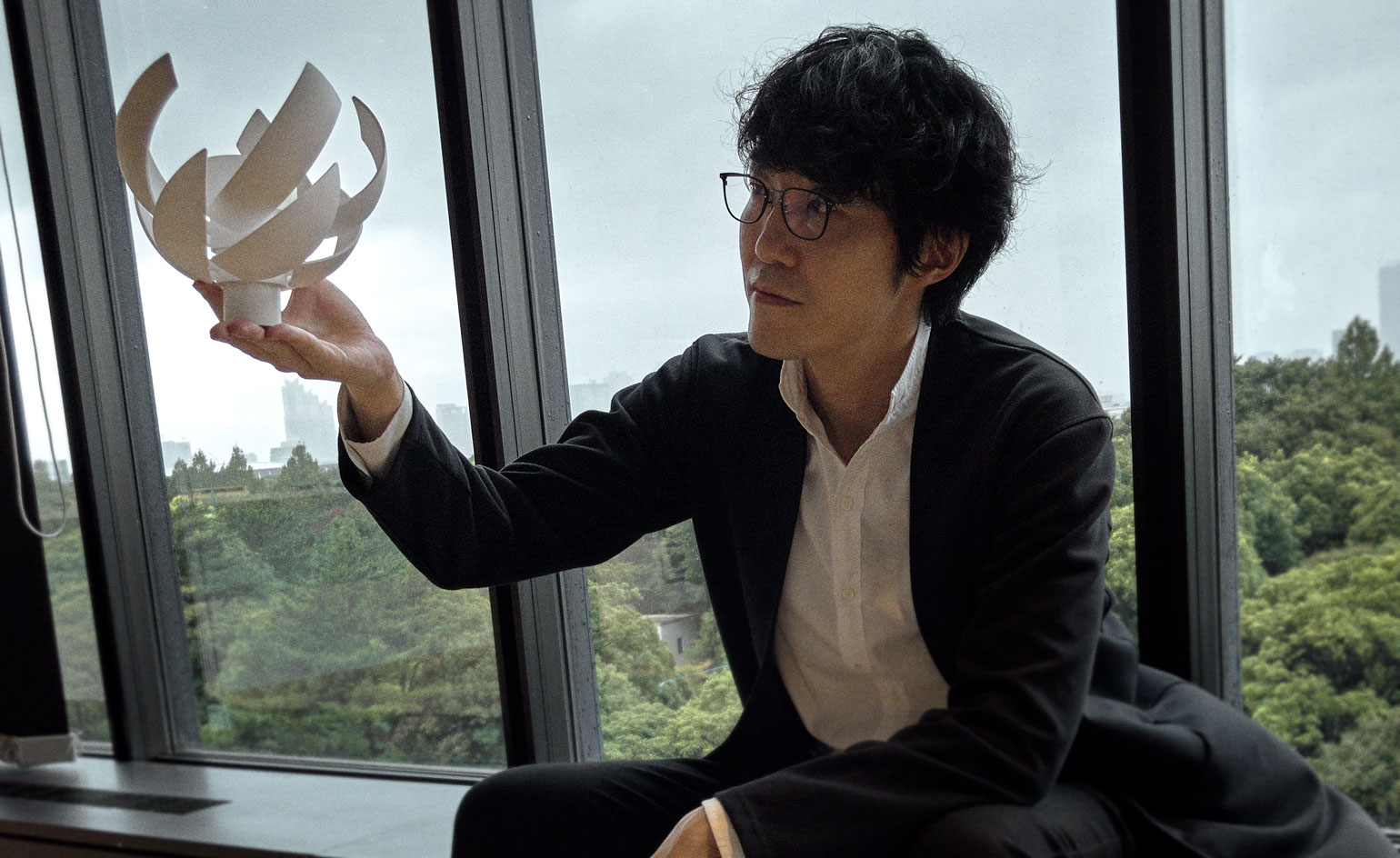

Nendo’s Oki Sato on challenges, new talent, and ‘taking the difficult way’

Oki Sato, founder of prolific Japanese studio Nendo, reflects on past and present challenges – including designing Tokyo’s Olympic cauldron – and, for Wallpaper’s 25th Anniversary Issue ‘5x5’ project, selects five young talents ready to pick up the torch

It’s not every day a creative is given carte blanche to ‘design flames’ – yet this was one key task among many which Oki Sato, founder of Japanese design firm Nendo, found himself tackling recently. These were admittedly no ordinary flames: perhaps the most famous in the world, they were created to flicker at the heart of the Olympic Cauldron, which was designed by Nendo for this year’s belated summer games in Tokyo.

Inspired by the sun, the white spherical orb blossomed into ten reflective aluminium panels beneath the night sky, opening like the petals of a flower in front of a global audience in July, before being lit by tennis player Naomi Osaka. The lighting of the cauldron was not only the final chapter in a painstaking design journey (a two-year process involving no less than 85 prototypes, combined with multiple pandemic challenges) – it also marked the apex of Nendo’s consistently upward trajectory since a freshly graduated Sato and four friends launched the design firm in 2002, in his parents’ garage in Tokyo.

Nendo’s Olympic Cauldron created for the Tokyo Olympics. Photography: Tokyo 2020

Over the subsequent two decades, the studio’s prolific output has been true to its name – nendo means clay in Japanese. Its ever-busy team (today totalling around 60, in Tokyo, Milan and Shanghai) are behind a malleable catalogue of projects nimbly spanning the creative spectrum, from homes and restaurants to furniture and interior products, with no detail of daily life overlooked – right down to milk carton-inspired soap dispensers and recyclable paper clips.

Playful, minimalist, innovative, clean-lined, functional and deeply rooted in daily life, Nendo creations – which always start with a simple sketch – are often instantly recognisable.

‘Mizuki’ vases, new designs by Nendo for Georg Jensen

Underpinning the studio’s creative DNA is the clean-lined simplicity and quiet colour palette of modern Japanese aesthetics, always balanced with a refreshingly universal perspective that is rare in Japan’s sometimes insular design industry.

A clue behind this global vision can perhaps be traced to Sato’s childhood: he spent the first ten years of his life in Toronto, before his family relocated home to Tokyo, an experience that enables him to navigate and experience the multi-faceted layers of Japanese life as both outsider and insider.

‘Thin Black Tables’, by Nendo, for Cappellini.

Nendo’s highlights – too many to list – range from ‘Hanabi’ (Japanese for firework), a minimalist white shape-memory alloy lamp which ‘blooms’ when switched on, unveiled at Milan Design Week in 2006; the graphic simplicity of ‘Thin Black Table’, produced for Cappellini in 2011; and the staggered cube-like formation of Kashiyama Daikanyama, a luxury complex which opened in Tokyo two years ago.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Not to forget the Olympic Cauldron, which has demanded exceptional attention to detail. There was the high-tech moulding of 10mm-thick aluminium plates by a special hot press machine; the ultra-low speed milling guided by laser scans to avoid distortion; and the extensive heat, fire and wind resistance testing of the polygonal mirror panels and compact internal drive unit.

And of course the flame itself – from the use of hydrogen (a first for the Olympics), generated through electrolysis of water from a solar power facility in Fukushima prefecture, where a nuclear disaster had struck in 2011; to the endless explorations of the perfect shade of flickering yellow, via sodium carbonate reactions, in addition to masterminding its angle, movement, shape and firewood-like shimmer.

Kashiyama Daikanyama commercial complex in Tokyo, completed in 2019, for the clothing company Onward.

Beyond the mix of design innovations and technological tinkering, the studio had to contend with a pandemic, as well as surging public opposition and an endless will-it-won’t-it-happen countdown to the games – it’s clear that this project was as complex and sensitive as it was high-profile.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Sato simply recalls a sense of ‘relief’ above all else when the cauldron – which he describes as ‘crystallising the essence of Japanese manufacturing’ – was finally unveiled to the world. ‘It was a project with a lot of pressure as it was not possible to fail,’ he explains. ‘The last six months were very tough mentally and psychologically. So I didn’t feel emotions such as joy, I was just relieved that the project finished without any major trouble.’

He adds: ‘I hope that many people could feel the vitality and energy behind the concept of the cauldron – not just the athletes, but also the many people still struggling from this pandemic. I hope it gave courage, and hope to those people.’

Top and above, items from Nendo‘s inflight amenity kit for Japan Airlines (JAL), unveiled earlier this year.

Sato is also all too aware that courage and hope are precisely what’s needed among a new generation of designers in Japan and beyond, who are juggling shifting global industry dynamics and the uncertainty of a pandemic with the challenges of launching their careers.

‘Now, many companies are observing the situation and refraining from investments and challenges,’ he says. ‘So huge branding projects and new projects may be rarer. And even if there were these projects, I feel that they would choose a designer with a stable history of accomplishment instead of giving the challenge to young designers, to lower the risk. The connection between young designers and society is getting looser and looser and I regard this as a serious problem. Also, if travel restrictions continue, this may lead to a decrease in engagement with designers from overseas, and in the presentation of new products.

‘It is possible for a mid-level designer who already has connections – they may continue projects using Zoom – but it is a different situation for designers starting from zero.’

In terms of his own efforts to support young creatives, he highlights how designers at Nendo are often allowed to work on a half-freelance basis after acquiring sufficient skill and experience at the studio.

‘This may help to maintain a longer relationship between us,’ he explains. ‘In Japan in the past, you basically had to choose between being a freelance or a salaryman. But to take the pros from both sides and make their status more ambiguous gives designers more opportunity for growth and the chance to perform a wider range of activities.’

Issey Miyake as mentor

When asked about mentors encountered on the pathway to his own success, Sato definitively cites perhaps Japan’s most iconic design name: Issey Miyake.

It was in 2008 when Sato was invited by Miyake to join a string of other young designers to create works for a new exhibition. The end result? The ‘Cabbage Chair’ – an organically unfolding structure fashioned from rolls of pleated paper left over from Miyake’s famed pleated textile process – which has since been globally celebrated and now sits in MoMA’s permanent collection.

‘Cabbage’ chairs, originally designed in 2008 for the ‘XXIst Century Man’ exhibition curated by Issey Miyake.

The experience was a milestone for Sato, not simply due to the affiliation with one of Japan’s most influential designers – but because of the invaluable creative lessons he learnt in the process.

‘I was trained as an architect, which meant I had a goal to fulfill and I needed to finish every project,’ reflects Sato. ‘However, Mr Miyake told me that I really didn’t have to finish the project. When you feel that it’s finished, it’s finished. That was interesting and inspiring – I learned that I am the one who creates the goal. That’s what makes design so free and interesting. Every project has a different goal.’

It’s a creative lesson that’s long lingered with Sato, who today has his own advice to offer designers starting out: don’t take the easy route.

‘There are always two paths to choose in any situation,’ he says. ‘The choices are the easy way and the difficult way. I strongly suggest taking the difficult way. The easier way can only give you the solution to the problem – but the difficult way will lead you to experiences and engagements that will benefit you in the future.’

Like many global designers, Sato’s own creative vision of the future has been dramatically recalibrated courtesy of the pandemic. Nendo’s output admittedly appears to have been no less prolific (this year alone, launches range from its online store Nendo House to amenity kits for JAL, while future projects include the interior design of France’s new high-speed TGV trains, to be unveiled ahead of the 2024 Paris Olympics, and an exhibition of collaborations with Kyoto craftsmen early next year).

Nendo introduces Nendo House, its online store

For a designer who used to pretty much live out of a suitcase (he was accustomed to a monthly round-the-world tour pre-pandemic), Sato describes the unusually long amount of time he has spent in Japan as a period of ‘overhaul’ – a moment to review past projects as well as plant creative seeds and incubate new ideas designed to flourish in a post-pandemic world.

‘It's a strange moment in my career because I haven't been abroad for more than two years,’ he says. ‘I can look back on our past activities and review each and every one of the things we have done so far. And perhaps the thoughts and arrangements I've made over the last two years will bring great value to Nendo in ten or 20 years.’

Meet Nendo’s five creative leaders of the future:

INFORMATION

A version of this article appears in the October 2021, 25th Anniversary Issue of Wallpaper* (W*270), on newsstands now and available to subscribers – 12 digital issues for $12,£12,€12.

Danielle Demetriou is a British writer and editor who moved from London to Japan in 2007. She writes about design, architecture and culture (for newspapers, magazines and books) and lives in an old machiya townhouse in Kyoto.

Instagram - @danielleinjapan

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

Nendo makes a splash with new designs for Flaminia

Nendo makes a splash with new designs for FlaminiaNendo launches two new product families – a countertop washbasin with wings and a tub-like lamp – for Flaminia’s 70th anniversary

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Nendo's recycled designs for Paola Lenti are inspired by cherry blossoms

Nendo's recycled designs for Paola Lenti are inspired by cherry blossomsPaola Lenti and Nendo unveil 'Hana-arashi' a series of sustainable furnishings inspired by Japanese culture at Milan Design Week 2024

By Maria Cristina Didero

-

Daniel Arsham interprets Nendo’s designs in new collaboration

Daniel Arsham interprets Nendo’s designs in new collaboration‘Break to Make’ at Milan Design Week 2023 features new interpretations of Nendo designs by American artist Daniel Arsham

By Maria Cristina Didero

-

At home with designer Sebastian Herkner

At home with designer Sebastian HerknerSebastian Herkner finds inspiration in his extensive travels around the globe and the spirit of optimism of his adopted hometown of Offenbach

By Rosa Bertoli

-

At home with Kelly Wearstler

At home with Kelly WearstlerAmerican designer Kelly Wearstler talks about her approach to interiors, her California homes, favourite LA spots, creative inspiration and more

By Rosa Bertoli

-

Ritesh Gupta’s Useful School: ‘Creative education needs to centre on people of colour’

Ritesh Gupta’s Useful School: ‘Creative education needs to centre on people of colour’Creative industry veteran Ritesh Gupta on launching Useful School, a new virtual learning platform that puts people of colour front and centre

By Pei-Ru Keh

-

Ilse Crawford judges Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022

Ilse Crawford judges Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022London Design Medal laureate Ilse Crawford – part of the six-strong jury for the Judges’ Awards, the Wallpaper* Design Awards’ highest honours – on design for a better reality, and our worthy winners

By Rosa Bertoli

-

Luca Guadagnino judges Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022

Luca Guadagnino judges Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022Italian film director Luca Guadagnino, who recently expanded his work into design and interiors, talks about his projects and judging the Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022

By Laura Rysman