Loom service: the Italian textile factory spinning remarkable yarns in its own good time

Impressive textile factories abound throughout Italy: many of them have been operating for more than 100 years, most are still family-run, and almost all are committed to upholding the quality and craftsmanship that have guaranteed the gold standard stamp of ‘Made in Italy’. But few dazzle with quite the same intensity as Bonotto, a 104-year-old company based in northern Italy’s Veneto region.

Two things make this factory unlike anything else in the country. First, the walls of the company’s unassuming offices, its roaring machine-filled factory and its grubby, stock-filled warehouse are all plastered with more than 17,000 works of contemporary art, producing a tangible sense of creative pride in everyone from its discerning design team to the regular muscle guys that lug around crates or huge rolls of heavy fabrics.

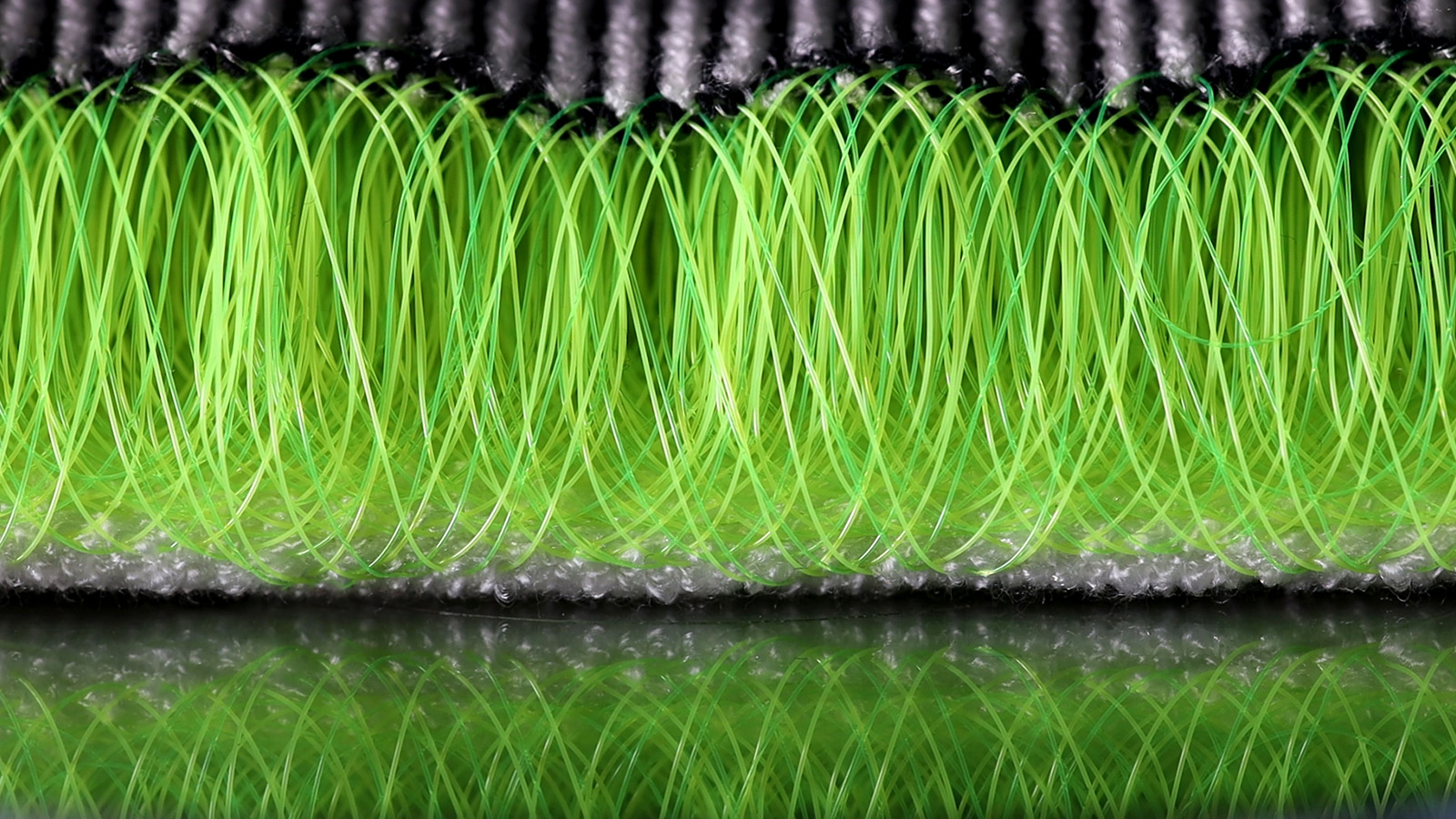

Secondly, the company specialises in ultra-feminine, luxurious materials that look more like works of art than fabrics for clothes. In today’s technology-obsessed world, most of these magical creations are still, incredibly, made on old-fashioned, mechanical looms that have long-since gone out of production.

‘I call it our Slow Factory,’ says creative director Giovanni Bonotto, great-grandson of founder Luigi Bonotto, as he walks past the enormous Dream screen, part of an art installation created by Yoko Ono in 2013 and which overlooks Bonotto’s complex yarn-spinning machines. ‘We are the Slow Food of the fashion industry.’

Located on a quiet street in a small town that both Danese and Diesel also call home, Bonotto has long been considered one of Italy’s top fabric suppliers. But in the last decade, as China became faster and cheaper, the company has purposefully become slower, more radical and, of course, costlier. It researches rare, difficult and unusual threads from around the world, including cellophane, chocolate wrappers, PVC, Tibetan yak hair, Afghan cashmere and non-genetically modified cotton from Zimbabwe, spinning them into yarns that purposefully look imperfect. It obsessively scouts for old machines that other companies throw out. It weaves fabrics slowly on old wooden looms from the 1950s that bang their shuttles back and forth like shotguns. And it specialises not in the buttery wools and cashmeres that are so central to Italy’s gargantuan menswear business, but in highly complex weaving processes in which more than 60 different yarns dissolve into thick, dense, richly patterned fabrics where, much like a tapestry or a painting, no single corner is the same.

‘Efficiency has killed so many beautiful details in fabrics,’ says Bonotto of his slow-moving machines, his oddball yarns and his ornate fabrics. ‘Here, artisans and intelligent hands can do things that the Chinese can’t.'

The innovation that comes out of Bonotto is creative catnip to the world’s top fashion designers. A quick spin through the factory reveals fabrics created for the best luxury brands: a swatch of an unusual houndstooth print has new colourways pinned on top of it for Bottega Veneta; a bolt of hefty rug-like fabric developed for Chloé last season stands upright in the corner; pages of notes from Chanel’s design team are pasted on top of brightly coloured woven ribbon tweeds; a rare nettle fabric made for Rick Owens unfurls on a table; while a navy and royal blue jacquard that just debuted on Giorgio Armani’s catwalk is half-woven on an old-fashioned loom on the factory floor.

Bonotto remains a much-loved secret weapon for fashion’s loftiest operators. While most people think designers invent their own fabrics, the reality is that behind-the-scenes creative talents, like those at Bonotto, do a good percentage of the design work before a fashion designer even puts pen to paper. In addition to the company’s seasonal commercial collection, offered to the industry at large, Bonotto creates custom-made textiles, conceived exclusively for particular designers to ensure that no one else has the same idea on their catwalks.

‘We sometimes suffer a little because we are inventing fashion here, but everything we do becomes invisible,’ says Bonotto. ‘We are never given credit for the things we make.’ Nevertheless, he is happy to be ensconced inside his creative cocoon, away from the harsh lights and pressure of the fashion world. ‘I hate fashion,’ he says. ‘I don’t feel a part of that world at all. I feel like a little artist hidden away in the countryside.’

As a child, Bonotto was surrounded by artists, from Marcel Duchamp and Jackson Pollock to Joseph Beuys and Nam June Paik, all of whom were invited by his art-obsessed father Luigi (grandson of the original Luigi) to stay and work in the area. In the 1970s, a formal artist-residency programme was started on the Bonotto campus and has since hosted hundreds of artists, all of whom have left their work in the bathrooms, stacked casually on office cabinets, hanging over the Coke machine in the foyer, and even inside the company’s Ikea-sized warehouse.

In 2014, it launched Bonotto Editions, a programme of art, installations and special projects conceived for public consumption. Curated by the brand’s creative director Cristiano Seganfreddo, Bonotto Editions began with a series of wall tapestries, including one by Italian architect Italo Rota. Last April, at Milan’s Salone del Mobile, it presented a 25-piece furniture collection designed by Matteo Cibic using Bonotto fabrics. This June, it produced an art installation at Pitti Uomo in Florence in which nine monumental tapestries, designed by artist Nanni Balestrini, upholstered the columns of the city’s Museo Novecento.

Back at the factory, the collection continues to grow. ‘At first our employees were worried,’ Bonotto remembers of his father’s decision to bring art on to the shop floor. ‘They asked, “Who would be responsible if something was broken or stolen?” But then they started to view their job as worth more. They looked at the machines differently and at themselves differently – with pride. Everyone is an artist here.’

As originally featured in the September 2016 issue of Wallpaper* (W*210)

Thinking Together, a 5m-long tapestry by architect Italo Rota and Bonotto Editions, designed for the XXI Triennale International Exhibition Milan. It took more than 1,000 working hours to make using ancient artisanal techniques and Japanese mechanical looms from the 1950s

Robot: The Baseball Player, 1989, by Nam June Paik, at Bonotto HQ

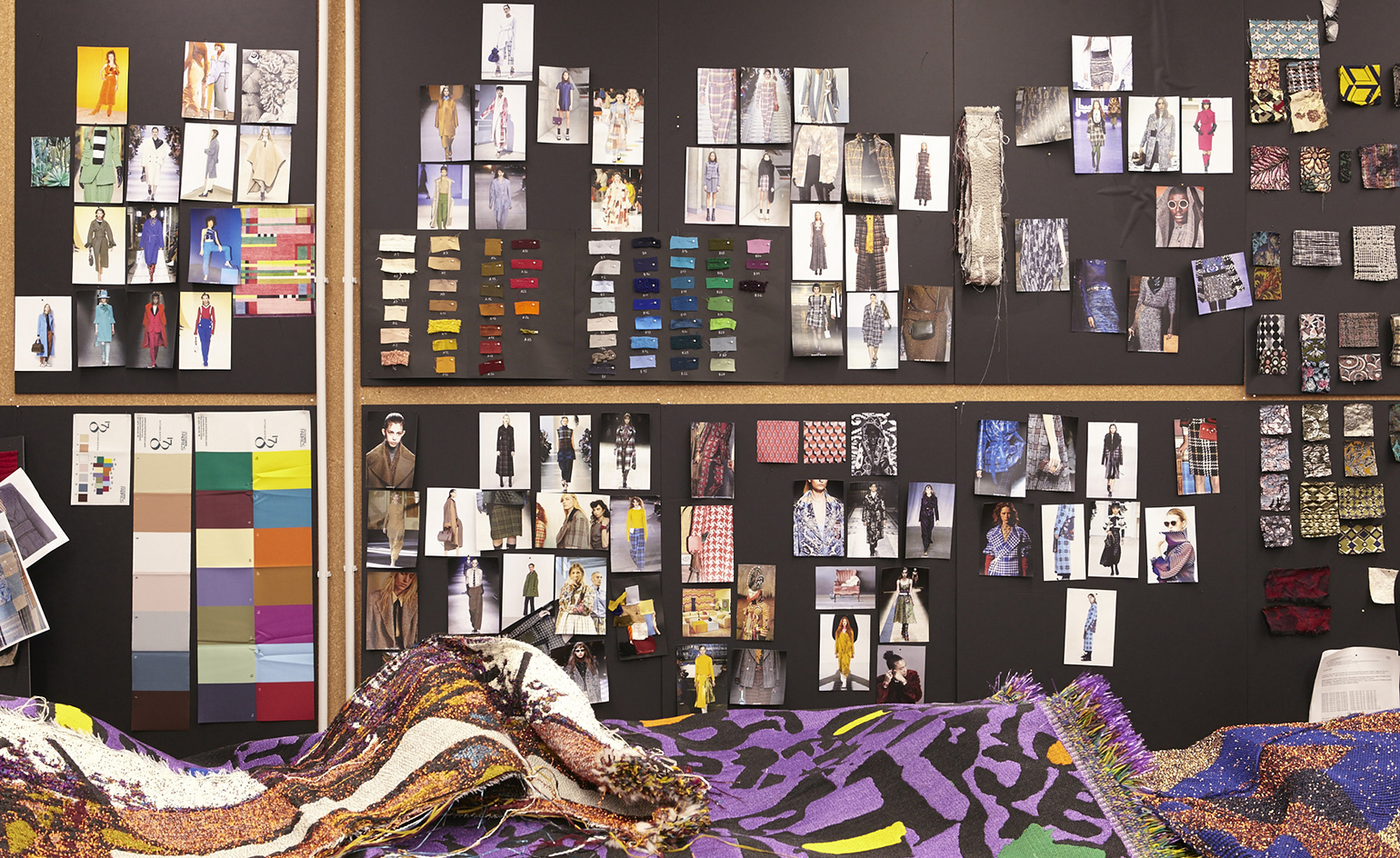

Samples and mood boards for tapestry designs and patterns

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Bonotto Editions website

Photography: Alberto Zanetti

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

JJ Martin

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

This Beirut design collective threads untold stories into upholstered antique furniture

This Beirut design collective threads untold stories into upholstered antique furnitureBeirut-based Bokja opens a Notting Hill pop-up that's a temple to textiles, from upholstered furniture to embroidered cushions crafted by artisans (until 25 March 2025)

By Tianna Williams

-

15 highlights from Heimtextil: spot the textile trends for 2025

15 highlights from Heimtextil: spot the textile trends for 2025We were at textile trade fair Heimtextil 2025 in Frankfurt last week – here are the trendsetters and names to know among innovative launches, from health-boosting lava fabric to sheets made of milk

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

Is Emeco's 'No Foam KNIT' a sustainable answer to synthetic upholstery textiles?

Is Emeco's 'No Foam KNIT' a sustainable answer to synthetic upholstery textiles?'Make more with less' is Emeco's guiding light. Now, the US furniture maker's new mono-material textile, the 'No Foam KNIT', may offer a sustainable solution to upholstery materials

By Ali Morris

-

Hella Jongerius’ ‘Angry Animals’ take a humorous and poignant bite out of the climate crisis

Hella Jongerius’ ‘Angry Animals’ take a humorous and poignant bite out of the climate crisisAt Salon 94 Design in New York, Hella Jongerius presents animal ceramics, ‘Bead Tables’ and experimental ‘Textile Studies’ – three series that challenge traditional ideas about function, craft, and narrative

By Ali Morris

-

Teruhiro Yanagihara's new textile for Kvadrat boasts a rhythmic design reimagining Japanese handsewing techniques

Teruhiro Yanagihara's new textile for Kvadrat boasts a rhythmic design reimagining Japanese handsewing techniques‘Ame’ designed by Teruhiro Yanagihara for Danish brand Kvadrat is its first ‘textile-to-textile’ product, made entirely of polyester recycled from fabric waste. The Japanese designer tells us more

By Danielle Demetriou

-

First look: Western Mongolia meets Kew Gardens in John Pawson and Oyuna Tserendorj’s cashmere throws

First look: Western Mongolia meets Kew Gardens in John Pawson and Oyuna Tserendorj’s cashmere throwsArchitectural designer John Pawson and cashmere designer Oyuna Tserendor have collaborated on a cashmere throw collection inspired by Pawson’s 70m Lake Crossing in the Royal Botanical Gardens

By Scarlett Conlon

-

Alcova to curate Heimtextil Trends 25/26: expect ‘inspiration and surprise’

Alcova to curate Heimtextil Trends 25/26: expect ‘inspiration and surprise’German textile fair Heimtextil has launched a new collaboration with Alcova, the experimental design platform. Here’s what to expect from the January 2025 fair

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

Sportswear logos, intimate portraits and a curled-up cat: Elizabeth Radcliffe’s beguiling tapestries go on show in New York

Sportswear logos, intimate portraits and a curled-up cat: Elizabeth Radcliffe’s beguiling tapestries go on show in New YorkAt Scottish artist Elizabeth Radcliffe's first US exhibition, a series exploring identity through branding is among works at Tribeca gallery Margot Samel

By Dan Howarth