Roya Mahboob on empowering women through design education

Design Emergency began as an Instagram Live series during the Covid-19 pandemic and is now becoming a wake-up call to the world, and compelling evidence of the power of design to effect radical and far-reaching change. Co-founders Paola Antonelli and Alice Rawsthorn took over the October 2020 issue of Wallpaper* – available to download free here – to present stories of design’s new purpose and promise. Here, Alice Rawsthorn talks to entrepreneur Roya Mahboob

Among the most heartening stories of design resourcefulness during the pandemic is that of five Afghan girls, aged 14 to 17, who have spent months designing and building emergency ventilators in the city of Herāt.

All members of the Afghan Dreamers team of young star roboticists, they are working on the ventilators as part of a series of projects organised by the tech entrepreneur, Roya Mahboob, chief executive officer of Afghan Citadel Software, in her philanthropic role as founder of the Digital Citizen Fund, which enables women and girls to learn more about technology to improve their technical literacy and employment prospects.

Mahboob spoke to Alice Rawsthorn about the Afghan Dreamers’ ventilator design project and her belief in the importance of educating girls in design and technology.

Alice Rawsthorn: You are involved with a number of design programmes that are seeking solutions to some of the problems posed by the pandemic. Could you tell us about them, starting with the Afghan Dreamers’ emergency ventilator design project?

Roya Mahboob: At the end of March, Abdul Qayoum Rahimi, then-governor of [the north-western Afghan province of] Herāt, put out a design challenge because there were very few ventilators in the region, which had a large number of cases of coronavirus. He was talking with doctors in Herāt, who were aware that the situation might be out of control. So, they put out a challenge to design open-source emergency ventilators and asked universities, manufacturers and the Afghan Dreamers to participate. Five members of our team responded to the call and started to build the ventilators.

The Afghan Dreamers team at work on their ventilator.

AR: As many of the world’s most powerful and well-capitalised manufacturers have discovered, it is incredibly difficult to design and build emergency ventilators. Not only do the Afghan Dreamers face a tough design challenge, they are tackling it in deeply difficult conditions having begun under lockdown. What extra levels of difficulty has this added?

RM: When the Afghan Dreamers started working on the ventilators, there was a lockdown in Herāt with many restrictions. The shops had closed, and it was a big challenge to find parts as we couldn’t go onto the streets to find them and didn’t know what was available. When you design any product, you need to have an idea of what’s on the market, so you can build it based on the available parts. That was the biggest problem for the team.

And, of course, their families were worried every time the girls left home, about security issues besides Covid-19. At the beginning, we had to fight to persuade them to allow the students to work on the project. We had to bring the girls to the office, but only had one car permit that allowed one car to go around the city. Another challenge was that we didn’t have the facilities to build some of the parts, so we had to go to a workshop 20 minutes outside the city.

And the most important thing is that we didn’t have access to some of the parts that are critical to building open-source ventilators: the medical sensors. Unfortunately, we couldn’t find them in Afghanistan. Indeed, we had to order them. Thank God they arrived. There were all these obstacles, and then of course, funding was another, and then none of us, none of our mentors and coaches, had worked on ventilators or any medical devices in the past. So, it was quite new and very challenging, but the girls were determined to work on this project.

AR: As you mentioned, Herāt has been one of the places in Afghanistan to be worst affected by Covid-19. As infections have continued to rise, what additional pressures have you faced?

RM: It actually encourages the girls to continue to work, when they see the numbers are increasing, especially now that people are treating the disease seriously. Unfortunately, people were careless before and it infected many, including some of the students’ family members, and even our mentors. It’s the worst part of the work, but it also makes the students more determined to continue.

But then, of course, you need to have the cooperation of the governor, you need to have the cooperation of the hospitals and doctors. And right now, the situation is that you can’t find doctors, because they are very busy with patients and they don’t have enough time to come and test the device. Of course, we appreciate their time and understanding, but the situation seems to be out of control.

Obviously, we have to be careful because this is a medical device and it should be tested thoroughly before being used. It could reduce the load of existing ventilators to help people who are in respiratory difficulty but not in critical condition. It is an automated add-on solution to a pre-existing bag; we call it the bag-valve-mask. It could be used in an emergency situation when a physician is present.

AR: What is the current status of the project? As I understand it, there is political support for it within Afghanistan and a determination that it will proceed.

RM: At the beginning, the former governor of Herāt was very excited because it was his plan. Then when he left office, we didn’t have that much support from the new governor, or even from the hospital, because the girls don’t have medical engineering degrees.

However, we have assembled a team of engineers who support us and fortunately, two weeks ago our president, Ashraf Ghani, mentioned in a cabinet meeting that he wanted the minister of health to look at our device and to support us. That meant a lot for us. We are very happy about that, and with the first devices, we have built. They have some functionality, which is good, and now we are working on the second prototype. We did a test ten days ago in a hospital in Herāt, which the doctors are very happy with. Next, we need to work on a second version, which is to make the ventilators clinically available in hospitals; we were waiting to receive the pressure sensors for this.

AR: What lessons have you learned from this? Clearly this is a remarkable project conducted under truly extraordinary circumstances that we hope will never be repeated, but what do you feel has gone well, and what do you feel you would tackle differently, should you approach anything like this again?

RM: We’ve learned a lot. One thing is that we have to think very fast and we have to make decisions fast. Another is to look at what’s really available in the market and which resources we have access to. The first two months were very, very diffcult for our teams, but we connected with so many people around the world. We learned how to ask for help, and that people are willing to help no matter where they are. And that even if they are not in Afghanistan, they are ready to support us.

Also, I think that if there is no pandemic, we will be a little more conservative when we next choose our projects, to make sure that our team and our resources will be available, and that we have enough support from the government and the community. The first month was very difficult because the governor changed, and the local hospital didn’t support us. But right now, people are happy with what the girls are doing. It has taken a long time, and some people are still sceptical, which I understand, but the government is supportive and, at least, allows the teams to work and to test the ventilators. So, I think that this process has been educational for us.

But it is also a great opportunity for us to show, as responsible citizens, what we can do for our community. I’m really very proud of these girls. They are very young, the youngest is 14 years old and the oldest is 17 years old. But they had the courage to do this. They said: ‘This is what we can do. This is our ability. Now we have to help our doctors and our nurses, and we have to help our government and our community.’ That’s how they started.

When we didn’t have motors, and I told them that we didn’t have enough resources, they said they were going to look for them in local markets and to find the gears from motorcycles. It has been interesting to see how they can find parts and put them together. They did the research to build one type of ventilator, then had more time to research and got inspired by a design from a team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), so they changed their design, and now they’re working on a new one.

AR: It’s an incredibly inspiring story. Many people have been touched by their dedication and courage. But you began a couple of other Covid-19 design projects as well. Could you tell us about them?

RM: We are working on a couple of other projects. One is an experiment with using UV-C light, which kills infection. Right now, another group of Afghan Dreamers is building two devices: a scanner and a robot that can be used in hospitals.

AR: You have had a phenomenal career in tech and design. What motivated you to found the Digital Citizen Fund, and to try to help other women and girls in Afghanistan to become tech literate and to pursue careers in technology design?

RM: I started with one dream and one goal. The dream was to make technology accessible for everyone. And the goal was to give access to technology and education to every woman, regardless of their social status and especially in Afghanistan.

Technology changed everything for me, professionally and personally, ever since I was 16 when I was introduced to this magic box. I think it is a powerful tool for women, especially in a conservative country. We have helped 15,000 girls to date, by educating them between the ages of 12 and 18. They learn how to work with computers, to build websites and games. They also learn about financial literacy, how to manage money, and how to start up on their own as entrepreneurs. Last year, more than a hundred of them started their own small businesses, which we’re very proud of.

Then, of course, we have official teams like the Afghan Dreamers, who are working on robotics, and another team of girls who are building games.

AR: Could you tell us about your plan to open an Afghan Dreamers Institute in Kabul to boost STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) teaching in Afghanistan?

RM: We are working on building Afghanistan’s first school of science, technology, engineering and medicine focusing on AI robotics, blockchain and cybersecurity. Fortunately, the Afghan government has given us a piece of land at Kabul University for the institute. We are trying to offer world-class education to Afghan students, focusing on women’s access to resources in the STEM field.

We seek to develop a foundation for lifelong learning and to promote economic development. And we believe this could be resolved by scientifically informed citizens and a creative, solution- seeking population that is trying to bring positive change. And, hopefully, the Afghan Dreamers will be Afghanistan’s future scientists, entrepreneurs and mathematicians. We’ll start fundraising for the institute after this pandemic.

AR: How has your experience of the pandemic, and of the design responses to Covid-19 you’ve championed, affected your ambitions for the Digital Citizen Fund?

RM: Before this crisis, we were organising a big conference, the Brite Initiative, to build resilience in technology, innovation and entrepreneurship. The idea was to showcase Afghan girls’ talent in technology, entrepreneurship and art using robotics or anything else, and to write a declaration that policymakers and donors should invest some part of their money in future jobs.

That was our mission and opportunity, but because of Covid-19 everything has been postponed – until next year, hopefully. I think that after the pandemic, people will understand the need for STEM education, and its power for Afghanistan.

The girls who are working on the ventilators are all under 18. Because they have experience and have had access to knowledge and education, they feel like responsible citizens working for society. This might send a big message to the government, governors and policymakers that they have to pay attention to the younger generation in Afghanistan. More than 27 million Afghans are under 25 and it is our government’s responsibility to pay attention to their education, because we all rely on this young generation for Afghanistan’s future.

AR: The Afghan Dreamers are demonstrating this with great aplomb. It is clear that the areas you’re focusing on – AI, robotics, blockchain and so on – will have huge growth in the future, but why do you believe they will be particularly important to Afghanistan? Is it related to Afghanistan’s cultural or artisanal traditions, for example?

RM: I’m Afghan, I grew up in this society, I feel responsible for my community and I’ve seen how powerful technology has been for many others. We have done a lot of projects here in Afghanistan, like Afghan Dreamers, that have had a huge impact.

But Afghan Dreamers won’t only be in Afghanistan, we believe that it should be implemented in other developing countries, whose younger generations need it. The idea of the Brite Initiative was to invite policymakers from the region to discuss this. I feel that in order to compete and prosper in the 21st century, more countries should be able to access the groundbreaking technologies that are transforming our world, but unfortunately, that’s not the case today. There is a huge gap between the richest and poorest countries and huge gaps within those countries that increase every day.

I started in Afghanistan because I have connections and resources here, and many years of experience of working in the tech sector. But we are already working in Mexico, trying to start the Mexican Dreamers Innovation Lab, and we’re making sure that we will be able to help dreamers in Pakistan, Palestine, Iran and other countries in this region, Africa and South America too.

INFORMATION

A version of this story appeared in the October 2020 issue of Wallpaper*, guest edited by Design Emergency. A free PDF download of the issue is available here.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

Amelia Stevens' playful, minimalist design 'is geared towards beauty as a function of longevity'

Amelia Stevens' playful, minimalist design 'is geared towards beauty as a function of longevity'In a rapidly changing world, the route designers take to discover their calling is increasingly circuitous. Here we speak to Amelia Stevens about the multi-disciplinary joy of design

By Hugo Macdonald

-

For Agnes Studio 'what matters is the emotional part: how you connect with design and designed objects'

For Agnes Studio 'what matters is the emotional part: how you connect with design and designed objects'In a rapidly changing world, the route designers take to discover their calling is increasingly circuitous. Here we speak to Agnes Studio about revitalising local traditions

By Hugo Macdonald

-

At home with designer Sebastian Herkner

At home with designer Sebastian HerknerSebastian Herkner finds inspiration in his extensive travels around the globe and the spirit of optimism of his adopted hometown of Offenbach

By Rosa Bertoli

-

At home with Kelly Wearstler

At home with Kelly WearstlerAmerican designer Kelly Wearstler talks about her approach to interiors, her California homes, favourite LA spots, creative inspiration and more

By Rosa Bertoli

-

Ritesh Gupta’s Useful School: ‘Creative education needs to centre on people of colour’

Ritesh Gupta’s Useful School: ‘Creative education needs to centre on people of colour’Creative industry veteran Ritesh Gupta on launching Useful School, a new virtual learning platform that puts people of colour front and centre

By Pei-Ru Keh

-

Ilse Crawford judges Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022

Ilse Crawford judges Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022London Design Medal laureate Ilse Crawford – part of the six-strong jury for the Judges’ Awards, the Wallpaper* Design Awards’ highest honours – on design for a better reality, and our worthy winners

By Rosa Bertoli

-

Luca Guadagnino judges Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022

Luca Guadagnino judges Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022Italian film director Luca Guadagnino, who recently expanded his work into design and interiors, talks about his projects and judging the Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022

By Laura Rysman

-

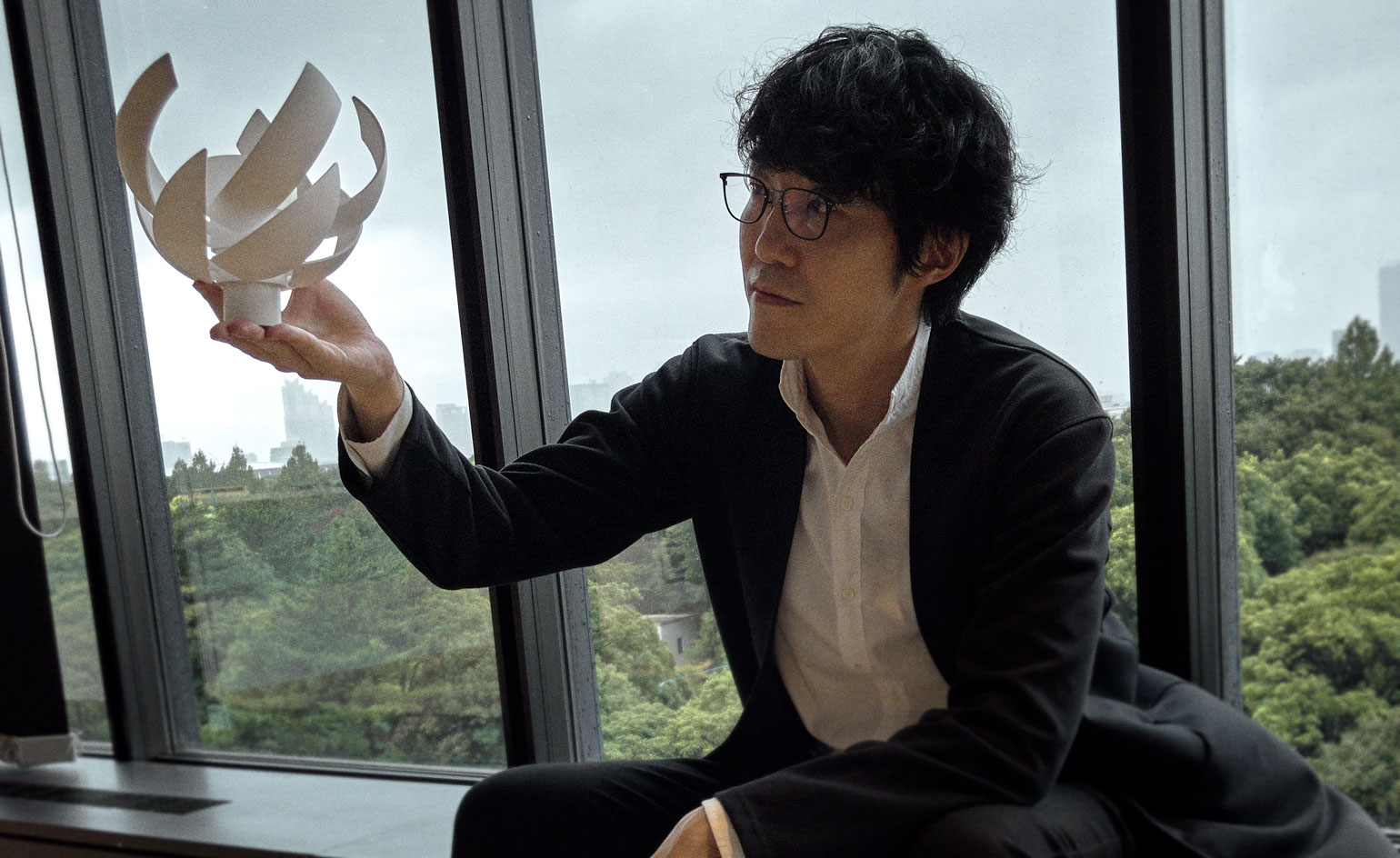

Nendo’s Oki Sato on challenges, new talent, and ‘taking the difficult way’

Nendo’s Oki Sato on challenges, new talent, and ‘taking the difficult way’Oki Sato, founder of prolific Japanese studio Nendo, reflects on past and present challenges – including designing Tokyo’s Olympic cauldron – and, for Wallpaper’s 25th Anniversary Issue ‘5x5’ project, selects five young talents ready to pick up the torch

By Danielle Demetriou