How two doctors designed a vital telemedicine service for Pakistan

Design Emergency began as an Instagram Live series during the Covid-19 pandemic and is now becoming a wake-up call to the world, and compelling evidence of the power of design to effect radical and far-reaching change. Co-founders Paola Antonelli and Alice Rawsthorn took over the October 2020 issue of Wallpaper* to present stories of design’s new purpose and promise. Here, Alice Rawsthorn talks to doctors Sara Saeed Khurram and Iffat Zafar Aga

Pakistan is a country of 200 million people, less than half of whom have access to a doctor. Two Pakistani doctors, Sara Saeed Khurram and Iffat Zafar Aga, decided to tackle this problem by designing a telemedicine service, Sehat Kahani, whereby female doctors who, like them, had stopped practicing to focus on their families, can work from home to treat patients in local clinics on live video links or apps. Founded three years ago, Sehat Kahani, which means ‘Story of Health’ in Urdu, now operates throughout Pakistan.

The two founders told Alice Rawsthorn how, having made an important contribution to the Covid-19 relief effort, their project now has the public awareness and political support required to accelerate its future growth, serving as an inspiring example of telemedicine’s potential to improve access to healthcare in countries where it is urgently needed.

Alice Rawsthorn: Why did you found Sehat Kahani?

Sara Saeed Khurram: It evolved around two major health issues. The first is very connected to my and Iffat’s lives – the issue of doctors’ rights. Pakistan has a total medical workforce of 170,000 doctors. Female doctors make up around 60 to 70 per cent of the total medical workforce, which is a great thing, but, unfortunately, only 23 per cent of them are currently registered with the Pakistan Medical & Dental Council and work, which means that 70,000 to 80,000 doctors are missing from Pakistan’s health ecosystem.

This happens because of what we call ‘doctor brides’, in that parents in our country want their daughters to become doctors, not for them to serve communities as physicians, but for them to have better hands in marriage. If you’re a woman in Pakistan, if you’re a doctor, if you’re tall, if you’re thin, if you’re pretty, you make the perfect package for an arranged marriage.

The second problem is very close to our hearts – the inaccessibility of healthcare in this country. Over half the population don’t have access to the help of qualified doctors and go to quacks, faith healers or midwives and nurses instead. While there are a lot of problems in the healthcare infrastructure, we believe that the inability of our medical workforce to work to its full potential contributes a lot to preventing the majority of the people in Pakistan from having access to healthcare.

Iffat and I both went through the doctor bride issue. When I had a small daughter, I couldn’t work and fell into postpartum depression, and Iffat lost her baby in a premature birth so left her job. The next time she conceived, she thought that she might lose the baby again. We felt that so many female doctors in Pakistan go through these traumas, that we could help by making provision for them to practice from their homes and to use telemedicine technology to connect to patients in communities where doctors are not accessible. That’s how Sehat Kahani came into being.

AR: What difficulties have you had to overcome since founding Sehat Kahani three years ago?

Iffat Zafar Aga: There were a lot of challenges. When we presented the concept, some people said it wouldn’t work. Telemedicine had come into Pakistan in the late 1990s, but most of those programmes were funded by donors. There were questions as to whether people would pay for telemedicine, how the system would work and whether patients would trust a doctor they could only meet online.

When we started reaching out to the right kind of communities for us to work with, it required a lot of education from our end to convince people that they would benefit from the initiative. In the early days we’d sit on the floor with women from those communities and explain what the service would be like for them, that the doctors lived in the city and had all graduated from prestigious hospitals. These were the challenges, but over time, we’ve overcome them and learned a lot along the way

AR: Was it also challenging for you to operate as an all-female team of doctors?

SSK: Yes, because Pakistan is still a patriarchal country, and many people still think that women are not able to do a lot of things. But one thing that has gone in our favour is that medicine is considered to be a noble profession in Pakistan, and while many female patients feel uncomfortable going to male doctors, we don’t see male patients being as uncomfortable about female doctors, because they respect the profession.

We started Sehat Kahani with the idea of creating telemedicine clinics in low-income communities, which are majorly patriarchal in nature, with the men taking all the decisions. When we started opening clinics with nurses working as intermediaries and helping the patients to connect to female doctors, one of the things that worked in our favour is that when women and children came in, they saw families getting consultations from a female nurse and a female doctor. So, there was limited male involvement in those clinics.

But as Sehat Kahani evolved, we added a mobile app to our service, to make it better suited to the mass market. Interestingly, 70 per cent of the market for our app are male patients, who are consulting female doctors and seem pretty happy about it. Yes, there are some issues, such as sex issues, urological issues, and psychological issues for which we also need male doctors. And we employ male doctors specifically for them. But, generally, we’ve seen that men are more comfortable for themselves and their families to consult female doctors, than to see male doctors.

AR: What was the role of design in Sehat Kahani’s development?

IZA: Design has been an essential part of how we have developed each and every service, and each and every product. We were very lucky in being associated with a lot of programmes that taught us about design. For example, we were part of the Spring Accelerator programme, which supports businesses whose products and services promise to improve the lives of adolescent girls. Spring Accelerator conducted external research in our communities to find out what healthcare services our patients would look for from a one-stop shop. Through this, we learned that women were not only looking to access general physicians, but as many healthcare services as is possible under one roof. So, for example, our community clinics now also offer access to ultrasound specialists on designated days.

We also learned that mental health is a very important problem faced by people in Pakistan, whether we’re talking about low-income communities or high-income communities. While the problems are the same in those communities, the way they are manifested can be very different and through these various design techniques we have been able to constantly evolve our services to better suit the users.

AR: How has Sehat Kahani responded to the Covid-19 crisis in Pakistan?

SSK: When Covid-19 happened, we were scared that as we don’t have a very robust healthcare system, it is very difficult for a country like ours to cope with this additional stress. When hospitals were brimming with Covid-19 patients, what would happen to patients who wouldn’t be able to get out of their homes? What about the women and children, and the chronic cases who would need help and wouldn’t be able to go to hospital?

Within our company, there was a very interesting scenario where our original base, the telemedicine clinics, had to close down because of the lockdown. We had a young app that had only been on the market for six months and was used by around 15 to 20 patients a day, and we had a corporate-care solution that was being used by six to seven corporates. We thought that either we can be agile and use this opportunity to provide healthcare to a lot of people, or we can sit around and wait for the telemedicine clinics to open again. We chose the first option. We put all our energy into our telemedicine app and went full force in making sure that it would be there whenever a patient needed a consultation with an online doctor. And we started working towards that by creating highly subsidized packages for our corporates and making our retail Sehat Kahani app free for all patients.

October 2020 issue of Wallpaper

RELATED STORY

Design Emergency Instagram Live service

We partnered with the federal government of Pakistan and provincial governments, and we partnered with corporates and NGOs to provide healthcare services to everyone who needed them. We created as much outreach as possible for our services, so that anyone who picked up a phone could contact a doctor using the Sehat Kahani app. And because of this, we went from seeing 12 to 15 patients a day on our app, to 700 or 800 patients a day: one in ten of them were suffering from Covid-19. There was also afirst-time mother who went into labour at 4am, whose husband was in Dubai working. She was all alone at home and didn’t know what to do. A Sehat Kahani doctor helped her get to a tertiary care facility for delivery. We had a 70-year-old man who suffered from cardiac failure in Balochistan, a very remote area of Pakistan with poor healthcare access. We were able to diagnose from his symptoms that he was going through cardiac failure. We had several mental health issues coming up on our app because of the lockdown and the economic crisis, and we were able to help those patients. I think this changed the course for Pakistan in terms of digital healthcare and for Sehat Kahani as a company.

AR: How did you restructure Sehat Kahani, and hire more doctors, to manage such a significant expansion in so short a period of time?

IKA: We already had a network of 1,500 physicians. The idea is that they become part of our bigger network where they engage in training and health education, so it has been a matter of mobilising the doctors from that pool whenever we needed them. As Sara explained, when we started doing so many more consultations, we had to mobilise up to 200 additional doctors to work on the app. At one point, we had somewhere around 300 to 350 doctors working on it. They were ready to serve and trained for the core protocols. That’s how we were able to adapt so quickly.

Whenever a doctor becomes a part of the Sehat Kahani network, they go through extensive training, which not only involves telemedicine, but how they can meet patients’ needs using software. They were all trained for Covid protocols, which evolve as government protocols change. We were constantly upgrading those protocols, and all the primary healthcare issues we could foresee through the mobile app. For example, we have had instances where suicidal patients have ended up calling general physicians and not mental health experts, so the general physicians also need to be trained to recognise that those cases need to be referred to specialists.

AR: What impact will your experience of Covid-19 have on Sehat Kahani going forward?

SSK: Covid has taught us a lot of things. Technology adoption in the country was extremely poor, or not at the standard we would have expected. We thought it would take another three to four years for people to really believe in the power of technology, and in the power of telemedicine. But Covid has made people in Pakistan understand its value. Our conversations with corporate partners, governments and stakeholders about telemedicine being the future of healthcare have become really easy. Corporates are subscribing every day. The fact that the federal and provincial governments partnered with a start-up to provide telemedicine services shows that even the government realises the value of digital healthcare.

When we talk about the future of healthcare in a country where the resources are so limited and the healthcare infrastructure is broken, telemedicine can play a very important role. Public healthcare is structured in Pakistan, much like in the UK. The patient goes to a basic healthcare unit, from there to a secondary health unit and then to a tertiary unit. What if we change all the basic health units into telemedicine units, so that each patient is seen by a virtual telemedicine physician rather than a nurse or a midwife? How many patients could you help in their communities with primary healthcare problems by doing that? This is a conversation that’s very easy to have with the government now, compared to before.

AR: How do you plan to develop the services you offer?

IZA: We’re always looking for new avenues. The idea is that for this year, we want to focus on expanding the mobile app services. Right now, we’re focusing on Pakistan, but we’re looking at scaling them in other countries too. We also see a huge opportunity in creating versions of the same app to be used by various healthcare facilities, by tertiary care hospitals, for example. And there are other areas of healthcare we can delve into.

AR: And how do you plan to take advantage of the new political support for your work and the growing awareness of it?

SSK: We’ll be talking to governments about a proper digital health policy, or for regulation or guidelines for digital health in the country. In order for any service to be legitimate, there has to be a policy or guidelines, which unfortunately are missing in Pakistan at the moment. We’re raising our voices on as many government, federal and provincial platforms as possible about this.

The second thing is that working with the government has given us credibility, so a lot of physicians want to come and work with us to set up virtual clinics using our mobile app.

We are also having conversations with the government about upgrading basic health units into telemedicine units. There are currently 6,000 to 7,000 units in Pakistan that are dormant and without doctors but could be upgraded. Of course, these will have to start as small pilot projects that can be upscaled if they show promise. Right now, one out of three people in Pakistan has access to a doctor. We can change that to two out of three. We also see ourselves as a telemedicine platform that can use Pakistani doctors to help other countries with limited access to healthcare. Bangladesh, for example, but also countries in Africa and Latin America. Our network of doctors and our telemedicine platform can be solutions for them, rather than just for Pakistan.

INFORMATION

A version of this story appeared in the October 2020 issue of Wallpaper*, guest edited by Design Emergency. A free PDF download of the issue is available here.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Marylebone restaurant Nina turns up the volume on Italian dining

Marylebone restaurant Nina turns up the volume on Italian diningAt Nina, don’t expect a view of the Amalfi Coast. Do expect pasta, leopard print and industrial chic

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Tour the wonderful homes of ‘Casa Mexicana’, an ode to residential architecture in Mexico

Tour the wonderful homes of ‘Casa Mexicana’, an ode to residential architecture in Mexico‘Casa Mexicana’ is a new book celebrating the country’s residential architecture, highlighting its influence across the world

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Jonathan Anderson is heading to Dior Men

Jonathan Anderson is heading to Dior MenAfter months of speculation, it has been confirmed this morning that Jonathan Anderson, who left Loewe earlier this year, is the successor to Kim Jones at Dior Men

By Jack Moss

-

Amelia Stevens' playful, minimalist design 'is geared towards beauty as a function of longevity'

Amelia Stevens' playful, minimalist design 'is geared towards beauty as a function of longevity'In a rapidly changing world, the route designers take to discover their calling is increasingly circuitous. Here we speak to Amelia Stevens about the multi-disciplinary joy of design

By Hugo Macdonald

-

For Agnes Studio 'what matters is the emotional part: how you connect with design and designed objects'

For Agnes Studio 'what matters is the emotional part: how you connect with design and designed objects'In a rapidly changing world, the route designers take to discover their calling is increasingly circuitous. Here we speak to Agnes Studio about revitalising local traditions

By Hugo Macdonald

-

At home with designer Sebastian Herkner

At home with designer Sebastian HerknerSebastian Herkner finds inspiration in his extensive travels around the globe and the spirit of optimism of his adopted hometown of Offenbach

By Rosa Bertoli

-

At home with Kelly Wearstler

At home with Kelly WearstlerAmerican designer Kelly Wearstler talks about her approach to interiors, her California homes, favourite LA spots, creative inspiration and more

By Rosa Bertoli

-

Ritesh Gupta’s Useful School: ‘Creative education needs to centre on people of colour’

Ritesh Gupta’s Useful School: ‘Creative education needs to centre on people of colour’Creative industry veteran Ritesh Gupta on launching Useful School, a new virtual learning platform that puts people of colour front and centre

By Pei-Ru Keh

-

Ilse Crawford judges Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022

Ilse Crawford judges Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022London Design Medal laureate Ilse Crawford – part of the six-strong jury for the Judges’ Awards, the Wallpaper* Design Awards’ highest honours – on design for a better reality, and our worthy winners

By Rosa Bertoli

-

Luca Guadagnino judges Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022

Luca Guadagnino judges Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022Italian film director Luca Guadagnino, who recently expanded his work into design and interiors, talks about his projects and judging the Wallpaper* Design Awards 2022

By Laura Rysman

-

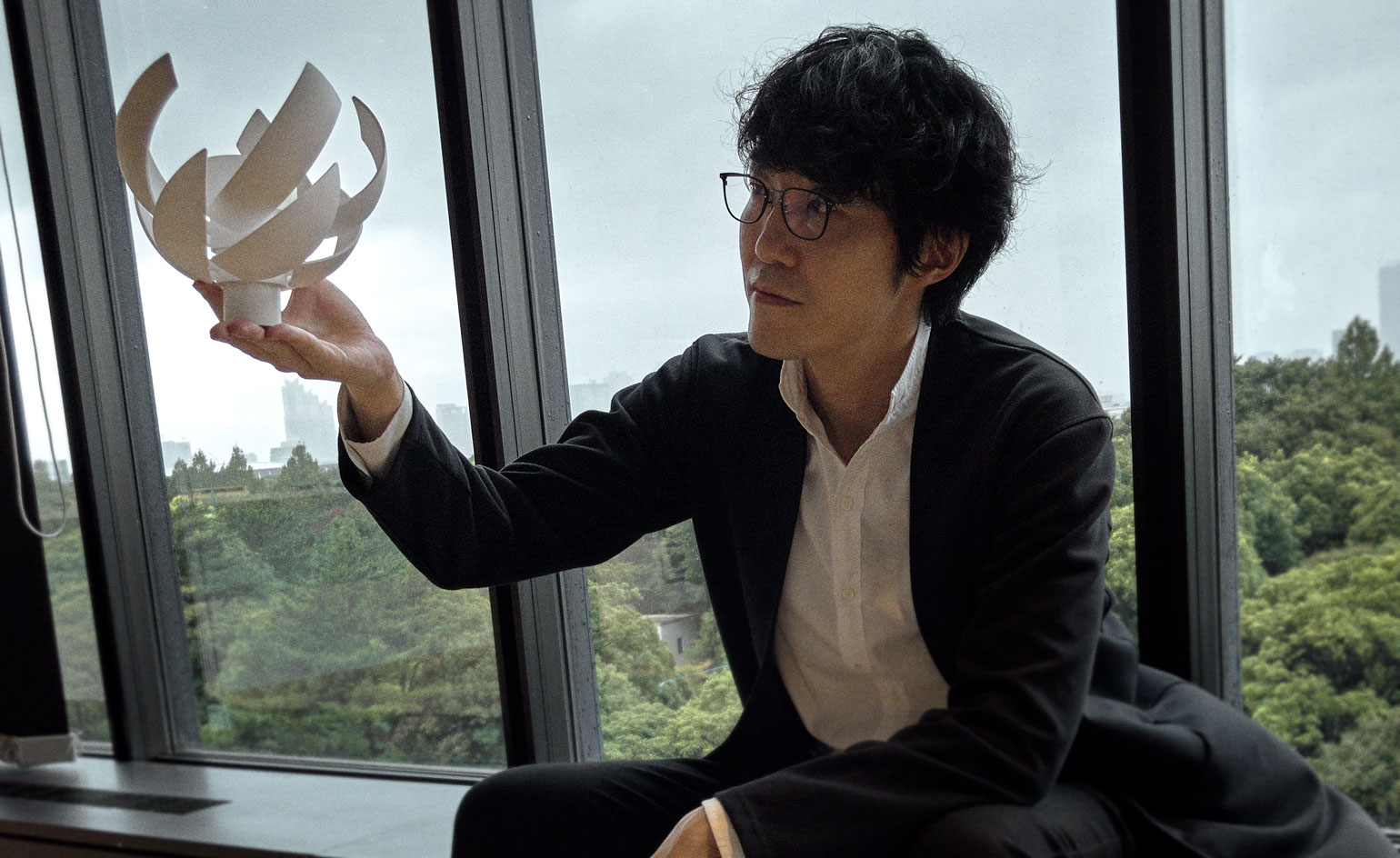

Nendo’s Oki Sato on challenges, new talent, and ‘taking the difficult way’

Nendo’s Oki Sato on challenges, new talent, and ‘taking the difficult way’Oki Sato, founder of prolific Japanese studio Nendo, reflects on past and present challenges – including designing Tokyo’s Olympic cauldron – and, for Wallpaper’s 25th Anniversary Issue ‘5x5’ project, selects five young talents ready to pick up the torch

By Danielle Demetriou