Drones flock, concrete hovers and lamps bloom as Studio Drift reimagines science and nature

In December 2017, Studio Drift unleashed Franchise Freedom, a formation of 300 drones fitted with a light source that went flying and flocking, as birds would, into the dark Miami night. Using computer algorithms, the studio added starling flight patterns to the drones’ software to emulate a phenomenon previously only seen, on this scale at least, in the natural world.

The Amsterdam-based studio, founded in 2007 by Netherlands-born artist Lonneke Gordijn and her British/Dutch partner Ralph Nauta, aimed to address the balance between the individual and the group, and how animals trade their individual needs for the safety of numbers. It was also a thrilling spectacle and perhaps a defining moment in ‘tech art’, the creative push and pull of technology into new shapes and forms.

The work of the interdisciplinary studio employs a special position in the tech art movement. Using sculpture, installation and performance, Gordijn and Nauta, who are both graduates of the Design Academy Eindhoven, take on the delicate, often destructive, relationships between human evolution, natural forces and technological advancement.

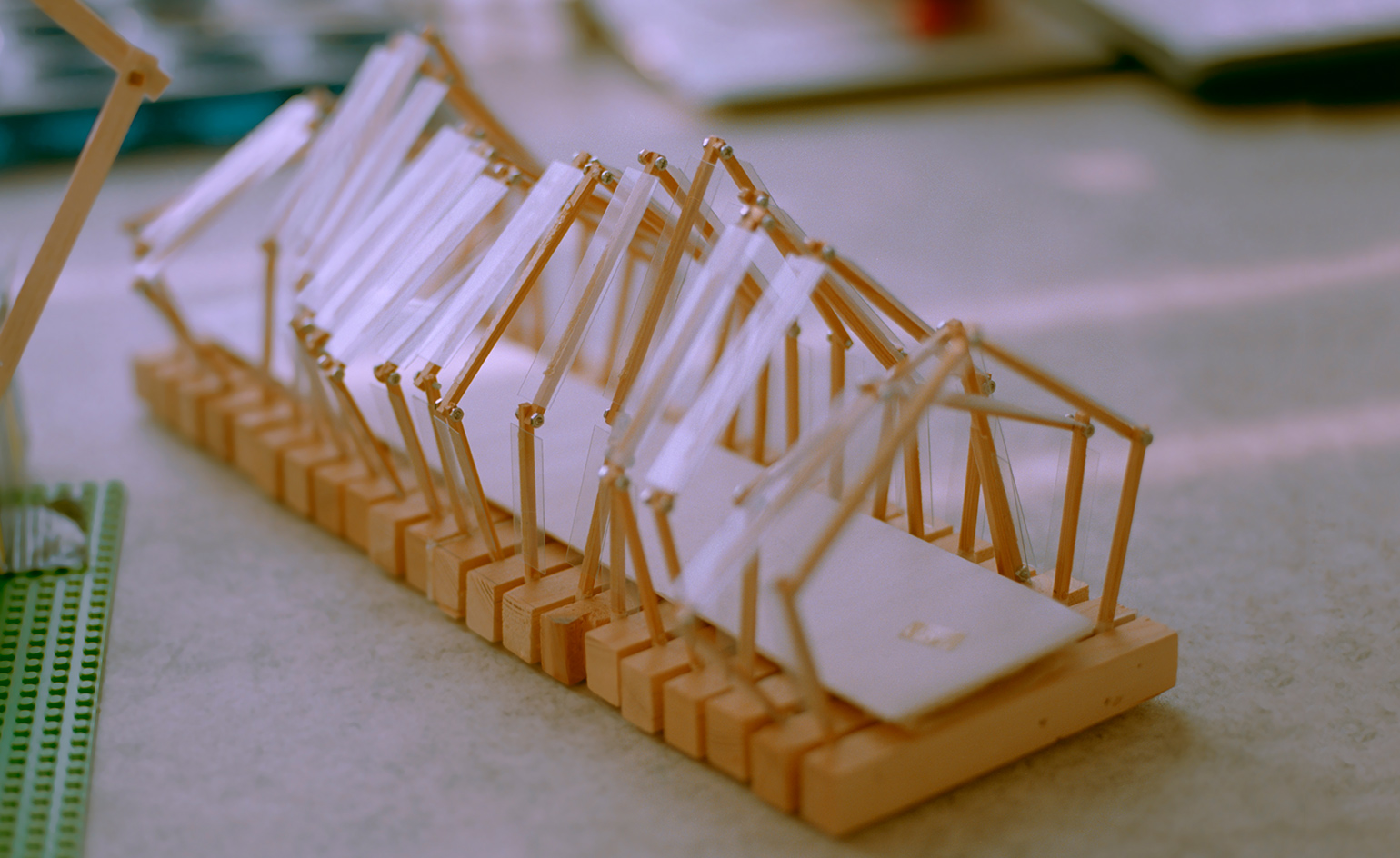

A Meadow module under construction in the studio.

Gordijn rose to international attention with her first light sculpture, Fragile Future, in 2005. Nauta later joined her in developing the project, which features delicate dandelion seed heads attached to LEDs, powered by bronze electrical circuits. ‘We were still finding out what our interests were,’ Nauta says. ‘I am very much interested in science fiction and Lonneke in natural processes. This project became the basis of Studio Drift.’

In 2007 and 2008, further versions of Fragile Future were shown at Salone del Mobile in Milan, where it caught the eye of the talent-hungry media and earned the pair a place in a show during 2008’s Design Miami. There they met Loïc Le Gaillard and Julien Lombrail, founders of contemporary design dealer Carpenters Workshop Gallery. ‘I still remember the emotion Loïc and I both had when we saw the work,’ says Lombrail. ‘It is so poetic and so romantic. What I really appreciate is that Lonneke and Ralph always keep their artistic integrity. They’re still working to their strict code of conduct and pushing for quality.’

A three-dimensional version of the light was developed for the gallery and shown at the 2009 PAD collectible design fair in Paris. To both parties’ surprise, the eight editions plus four artist’s proofs sold out. ‘Suddenly we found our market,’ says Gordijn. ‘But the clients in this specific market are looking for functionality, and we never wanted to make “lamps”. We need to be freed from limitations.’ Studio Drift was part of a new wave of tech-obsessed conceptual designers, including Troika, Random International and TeamLab, who were treading a new path and stretching old definitions to breaking point. If design couldn’t contain them, art could.

Fittingly perhaps, the impact of social media has accelerated Studio Drift’s rise in the contemporary art world. In 2014, Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum bought Shylight, a light sculpture that imitates the biological rhythm of plants. Five of its modules are now permanently on view in the new Philips Wing of the museum. Videos of the dancing sculpture went viral on the internet and accumulated 22 million views. This new engagement with more visually dynamic art has transformed the relationship between the museum and its audience.

Work in progress on Fragile Future modules, which feature dandelion seeds glued to LED lights.

Last March, Studio Drift entranced the art world again with Drifter, a massive ‘concrete’ block that appeared to float mid-air, tilting as if of its own accord, presented by the Pace Gallery at the Armory Show in New York. ‘Five hundred years ago, concrete was a sci-fi idea,’ says Gordijn, adding that it was Thomas More who mooted the idea of a durable, easy material with which to build robust homes in Utopia. ‘Those powerful wishes and ideas drive innovation, and the human race, forward.’

The internet and social media might have improved the studio’s fortunes, but the pair are cautious about the benefits of virtual attention. ‘It shouldn’t be about how many likes and followers we generate, but the underlying reason for the piece being created,’ says Nauta. ‘Artists should be very careful that what we are doing doesn’t become a fashion; it takes time to produce quality.’

This spring they will get their biggest stage yet when their first solo exhibition, ‘Coded Nature’, opens at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum. The opportunity came at the eleventh hour – a Sottsass exhibition was called off, freeing up a key slot on the museum’s calendar. Ingeborg de Roode, curator of industrial design, acknowledges that the museum has been following the pair’s work from the beginning. ‘It is important that they show the public what can be done with technology. While some people feel it is scary, it is good to discuss different views about it,’ she says. ‘Studio Drift uses technology in a positive and poetic way, creating exciting experiences.’

Alongside Drifter, the largest-ever Fragile Future installation and other greatest hits, the exhibition will also include a new installation, Elementism. ‘It is a starting point of a research project, based on the elements that make up our world, to realise what our responsibilities are to everything we take from the Earth.’ Objects will be deformed and reshaped into cubes of their base materials. Gordijn says Elementism shows the very power of ideas. ‘When you take the idea away from an object, you have only the material left.’

An early sketch of the design created by Gordijn for her graduation project at the Design Academy Eindhoven.

The pair are also working on new projects to be revealed later this year, including a large light sculpture that aims to change the landscape and skyline of an American city, and a moving pavilion for the gallerist Philippe Gravier. ‘This time we are creating the whole space as an experience,’ says Gordijn. ‘The scale is challenging.’

Having a wider stage means greater responsibilities, but also the potential to start new conversations. ‘One of our missions is to become a serious partner in important technological developments. We cannot approach it from a purely technical point of view. We have to approach from an intuitive and emotional perspective. After millions of years being human beings, we still need safety, we still need food, we still need love – these are the essentials, and technology should support life in that way,’ says Gordijn.

And Studio Drift is wasting no time. The duo are ready to build a new base, fit for this broader mission. They are collaborating with OMA on part of the architects’ redevelopment of Bijlmerbajes, a former prison complex in Amsterdam, which they aim to turn into a collective workspace, research centre and laboratory. ‘We are recruiting interesting design and art studios that are working along the same lines as we are, and we want to work on future solutions with technology partners,’ Gordijn says. ‘It is also a statement to the outside world.’

As originally featured in the May 2018 issue of Wallpaper* (W*230)

Meadow modules, under construction in the studio, will be shown at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum. Made of ingenious robotics and layers of silk, the lights fold and unfold to perform a mechanical ballet inspired by flowers.

A model of a moving pavilion for Philippe Gravier

INFORMATION

‘Coded Nature’ is on view from 25 April until 26 August. For more information, visit the Stedelijk Museum website and the Studio Drift website

ADDRESS

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Stedelijk Museum

Museumplein 10

1071 DJ Amsterdam

Netherlands

Yoko Choy is the China editor at Wallpaper* magazine, where she has contributed for over a decade. Her work has also been featured in numerous Chinese and international publications. As a creative and communications consultant, Yoko has worked with renowned institutions such as Art Basel and Beijing Design Week, as well as brands such as Hermès and Assouline. With dual bases in Hong Kong and Amsterdam, Yoko is an active participant in design awards judging panels and conferences, where she shares her mission of promoting cross-cultural exchange and translating insights from both the Eastern and Western worlds into a common creative language. Yoko is currently working on several exciting projects, including a sustainable lifestyle concept and a book on Chinese contemporary design.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

TEFAF Maastricht 2025 is a brush with wonderfully niche art, design and antiquities

TEFAF Maastricht 2025 is a brush with wonderfully niche art, design and antiquitiesWhat we saw and loved at TEFAF Maastricht 2025 (on until 20 March), from surrealist Claude Lalanne’s daybed and Ancient Egyptian jewellery

By Harriet Quick

-

Alessi Occasional Objects: Virgil Abloh’s take on cutlery

Alessi Occasional Objects: Virgil Abloh’s take on cutleryBest Cross Pollination: Alessi's cutlery by the late designer Virgil Abloh, in collaboration with his London studio Alaska Alaska, is awarded at the Wallpaper* Design Awards 2023

By Rosa Bertoli

-

Design Miami 2022: highlights from the fair and around town

Design Miami 2022: highlights from the fair and around townDesign Miami 2022 (30 November – 4 December) aims at ‘rebooting the roots of our relationship with nature and collective structures, ecospheres, and urban contexts’

By Sujata Burman

-

Salon Art + Design 2022: design highlights not to miss

Salon Art + Design 2022: design highlights not to missWallpaper* highlights from Salon Art + Design 2022, New York

By Tilly Macalister-Smith

-

Design Week Lagos 2022 celebrates creativity and innovation in West Africa and beyond

Design Week Lagos 2022 celebrates creativity and innovation in West Africa and beyondCurated by founder Titi Ogufere, Design Week Lagos 2022 is based on a theme of ‘Beyond The Box’

By Ugonna-Ora Owoh

-

Designart Tokyo transforms the city into a museum of creativity

Designart Tokyo transforms the city into a museum of creativityDesignart Tokyo presents global design highlights through a series of exhibitions involving global creative talent and traditional Japanese craft

By Danielle Demetriou

-

Tom Dixon marks his studio's 20 years with a show of design experiments

Tom Dixon marks his studio's 20 years with a show of design experimentsMushroom, cork, steel coral and more: Tom Dixon showcases an overview of his design experiments as he celebrates his practice's 20 years

By Rosa Bertoli

-

Vitra unveils new London home in the Tramshed, Shoreditch

Vitra unveils new London home in the Tramshed, ShoreditchLondon Design Festival 2022: after a year-long renovation, Vitra opens the door to its new showroom in the heart of Shoreditch

By Rosa Bertoli