Buried treasure: sustainable sarcophagus, by Tom Dixon and Paper Factor

Death is the terrifying ‘elephant in the room’ for many cultures, a topic that no one wants to talk about, let alone design products for. Our obsession with youth has led to an oversupply of objects designed for the early stages of life, yet there is very little in the way of elegant products for its end.

It’s a fact that hasn’t gone unnoticed by one designer in particular, who when asked to consider the spiritual passage for Wallpaper* Handmade, seized upon the chance to broach that taboo. ‘It’s something I’ve been trying to do for quite a long time,’ says trailblazing British designer Tom Dixon of his sustainable sarcophagus. ‘I’ve been thinking about the idea since I was at Habitat (where Dixon served as creative director from 1998 to 2008). So you could say that Wallpaper* has made my dreams come true.’

With its streamlined form, Dixon’s lightweight paper coffin is an elegant overhaul of an outdated design. ‘I bought a coffin to look at the construction, and I put it in the staff room,’ remembers Dixon of the early stages of the project. ‘Everybody in the office freaked out, which is really a reflection of the symbolic grip that coffins have on the popular imagination.

‘Death is weirdly ignored, until it happens,’ he continues. ‘And when it happens, the rituals and the artifacts around it are from another era, and have all kinds of awful connotations. Even the shape of a coffin and the way it’s constructed reeks of horror movies, Victoriana and Gothic and the rest of it. Nothing’s really progressed – there are wicker coffins, and the cardboard ones for eco-warriors – but you don’t get anything that reflects the personality of the person whom you’re celebrating.’

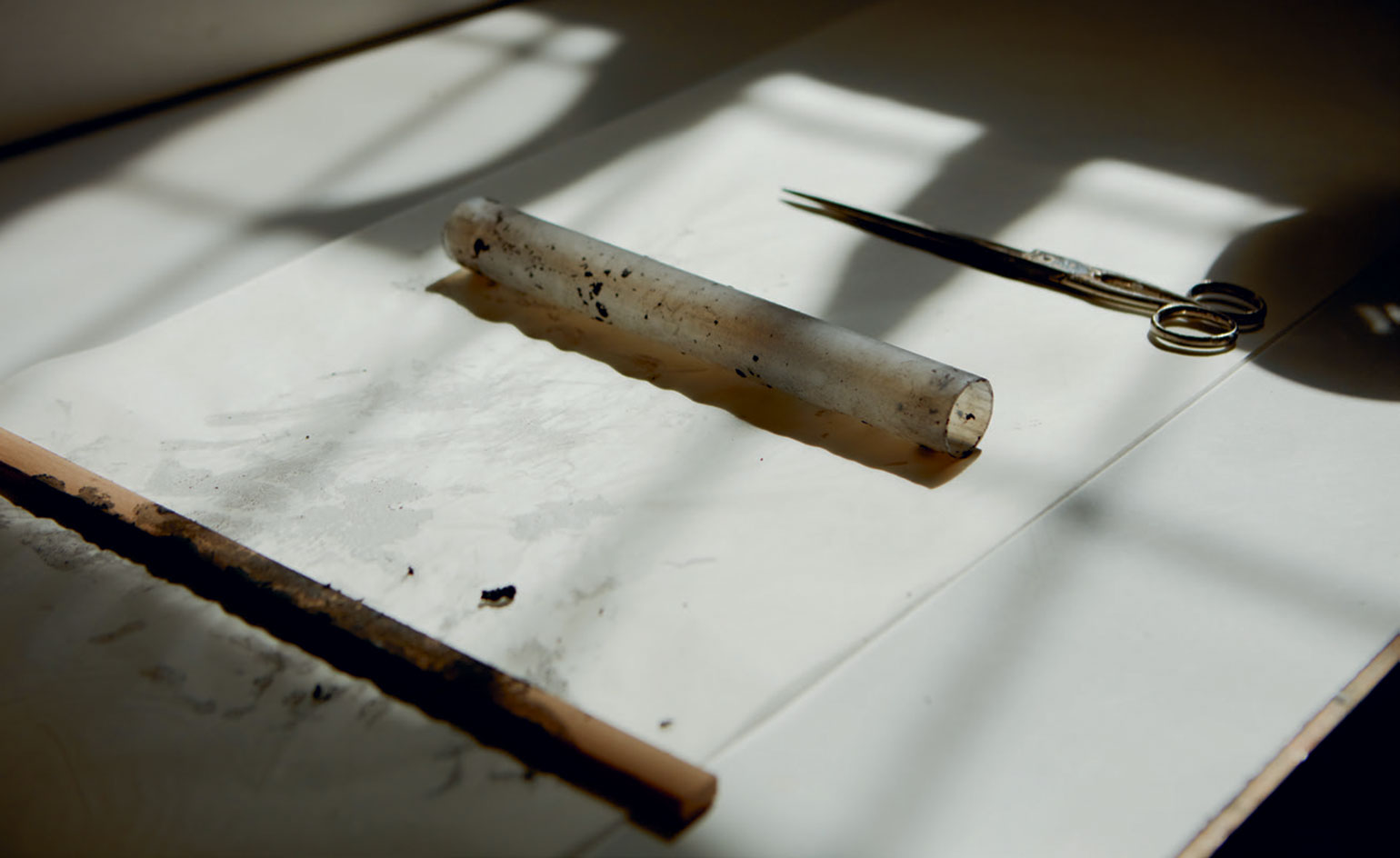

Cavaciocchi’s tools include non-stick paper, scissors and a roller

Concluding that the current coffin options were ‘pretty grim’, Dixon began to look further afield for inspiration, researching positive rituals that take place in the cultures of Egypt and sub-Saharan Africa, where the deceased are given celebratory send-offs. It was the natural, rounded shape of Egyptian sarcophagi that particularly appealed to Dixon, and so he set about creating a design for a soft and organic case – the antithesis of the traditional sharpcornered, brass-handled designs.

Dixon and Wallpaper* set off in search of a perfect contemporary material with which to realise this design. The quest led us to new Italian brand Paper Factor, which offered the perfect solution. Similar to papier mâché, Paper Factor’s eponymous cellulose compound is strong, durable, mouldable and extremely light.

In addition, its manufacturing process uses sustainable timber sources, avoids hazardous substances and generates minimal waste, making it an ecologically sound choice to boot.

New York-based architect Riccardo Cavaciocchi is the man behind the micropaper material. Originally invented by his mother, the accomplished Italian art restorer Lidiana Miotto, the material has been produced by Cavaciocchi’s family for over 35 years and used for the restoration of ancient artworks; but it was only last year that Cavaciocchi started to develop it for other applications. Realising that the material could potentially be used in architecture and interior design, he began producing a series of decorative surfaces in a variety of sizes and finishes. Cavaciocchi hopes that the new Paper Factor venture will introduce his family business to a fresh audience.

Production is still based in Cavaciocchi’s home town of Lecce in Apulia, an area with a long-standing history of paper production. ‘A huge part of the restoration work that my mother used to do in the past was related to religion,’ recalls Cavaciocchi. ‘She restored the ceiling of an ancient church here in Lecce, and she’s also made many religious statues and monuments. So being asked to produce a coffin by Wallpaper* didn’t seem out of the ordinary for us, though it was a pleasant surprise. To be honest, I was much happier to produce a big object like this, rather than a chair.’

Pressing the raw pulp down between two wooden guides

The process of creating the monolithic sarcophagus began by dyeing rough paper pulp with natural pigments, to create the earthy black and brown shades that Dixon desired. The pulp was applied as square tiles onto a polystyrene mould by hand, and smoothed into a single form. After being left to dry slowly and naturally in a special chamber, the dried paper cast was trimmed, calibrated and polished manually and with CNC machines. The resulting ceremonial casket possesses an organic texture that evokes the return of ashes to ashes.

‘The Paper Factor compound is very easy to adapt to any shape of mould,’ explains Cavaciocchi. ‘So it was very simple to begin the process. The only thing is, when the dimensions are bigger you have to take care because it’s more easily damaged, and we’d never done something like this before. But the design is beautiful, it’s clean, it’s pure, it’s minimal. It looks so solid and heavy but actually it is so light.’

For Dixon, the use of the paper compound was a first. ‘I’ve looked quite a lot previously into paper pulp packaging and things like that, so I know how it works in terms of the moulding process – and I’ve done a bit of papier mâché in my time,’ adds the designer with a smile, ‘but this project was never supposed to be about pushing the boundaries in terms of papier mâché, it was about trying to find a neutral but recognisable form to envelope the body.’

As for the future of the project, Dixon is pragmatic. ‘I’ll definitely try and work with Riccardo again as I love the technique,’ he says, ‘but maybe on something with more consumer appeal. Hopefully people will recognise that we’re able do more than make chairs and lamps and, you never know, perhaps I’ll be getting a few calls from the coffin makers out there.’

As originally featured in the August 2017 issue of Wallpaper* (W*221)

The paste has to have a uniform thickness of about 1cm

Cutting out the excess pulp to form perfectly square tiles

Checking the edges are as straight as possible

Lifting a paper pulp square to put it into place

Pressing the square into position on the mould

Removing the non-stick paper before starting to work on the next tile

Cavaciocchi produced two coffins for the project in earthy shades created by dyeing the paper factor pulp with natural pigments

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Tom Dixon website and the Paper Factor website. Available from WallpaperSTORE*

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Ali Morris is a UK-based editor, writer and creative consultant specialising in design, interiors and architecture. In her 16 years as a design writer, Ali has travelled the world, crafting articles about creative projects, products, places and people for titles such as Dezeen, Wallpaper* and Kinfolk.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

‘The future is hypermobile’: portability guides Tom Dixon’s Coal office exhibitions

‘The future is hypermobile’: portability guides Tom Dixon’s Coal office exhibitionsLondon Design Festival 2023: at Coal Office, Tom Dixon explores themes of hypermobility in collaboration with cutting-edge contemporary brands, mixing AI, tech and research

By Rosa Bertoli

-

At home with Tom Dixon interview: ‘humour is essential for sanity’

At home with Tom Dixon interview: ‘humour is essential for sanity’Tom Dixon speaks to Wallpaper* ahead of his Euroluce debut: the green-fingered godfather of British design on everything from espressos and eelgrass to curiosity and collecting heads

By Rosa Bertoli

-

Pitch perfect: ‘Love Rocker’, by Owen Bullett Studio and Heerenhuis

Pitch perfect: ‘Love Rocker’, by Owen Bullett Studio and HeerenhuisFor Wallpaper* Handmade X, sculptor Owen Bullett and table manufacturers Heerenhuis devised a rocking chair for two

By Anna Winston

-

Wet set: ‘Three Isles’ birdbaths, by Teo Yang Studio and Huguet

Wet set: ‘Three Isles’ birdbaths, by Teo Yang Studio and HuguetBy Blaire Dessent

-

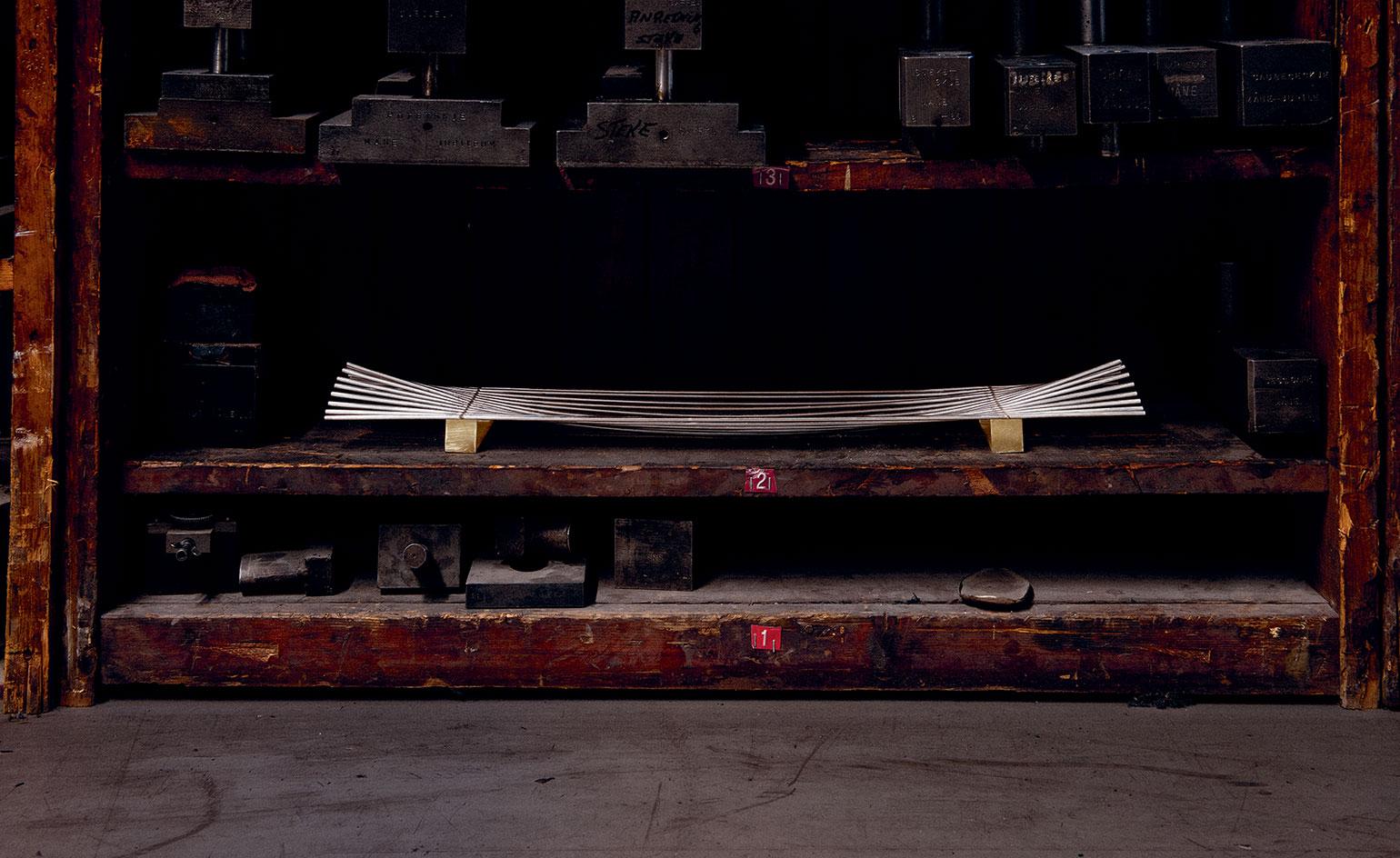

Artisanal precision is at the core of the ‘Arched’ centrepiece

Artisanal precision is at the core of the ‘Arched’ centrepieceFor Wallpaper* Handmade X, Norwegian silver manufacturer Arven and Design Academy Eindhoven graduate Guglielmo Poletti design a seemingly simple ‘conversation piece’

By Rosa Bertoli

-

Lars Beller Fjetland and Bottega Ghianda craft love birds

Lars Beller Fjetland and Bottega Ghianda craft love birdsFor Wallpaper* Handmade X, Norwegian designer Lars Beller Fjetland and Italian workshop Bottega Ghianda translated the romantic symbolism of the duck into ‘Amaranth’, a series of stylised bird figurines

By Rosa Bertoli

-

We're tickled pink by Design Haus Liberty and Yerra's Peruvian alpaca picnic set

We're tickled pink by Design Haus Liberty and Yerra's Peruvian alpaca picnic setLuxury rug maker Yerra and architecture studio Design Haus Liberty humanely sourced the finest Peruvian alpaca fur for ‘Isla’ – an ethical and sustainable Wallpaper* Handmade X project

By Henrietta Thompson

-

How Coffey Architects and Compac joined forces to design a quartz table

How Coffey Architects and Compac joined forces to design a quartz tableFor Wallpaper* Handmade 2018, we challenged Coffey Architects and marble and quartz manufacturer Compac to create a hybrid design inspired by the theme of wellness. Here, we go behind the scenes to find out how the Stepwell table was bought to life

By Harriet Thorpe