The making of ‘Taking Care of Wild Relatives’, by Sebastian Herkner, Lobmeyr and FAO

The Viennese crystal and chandelier manufacturer Lobmeyr knows a thing or two about fine craftsmanship. Founded in 1823, it was a pioneer of Austrian and Bohemian crystal production, supplying the Imperial Court and the world with fine tableware and chandeliers, perhaps the most famous of which adorn the Metropolitan Opera in New York. The secret to the firm’s longevity – the family business, run by Leonid, Andreas and Johannes Rath, is currently in its sixth generation – lies in the combination of its great craftspeople and a thirst for innovation. They were the first to make chandeliers using Edison’s electric light bulbs in 1883, worked with the likes of Adolf Loos and Josef Hoffmann in the early 20th century, and designers such as Formafantasma, Michael Anastassiades, Philippe Malouin and Helmut Lang in the 21st.

So when Wallpaper* paired Lobmeyr with one of the world’s most acclaimed young product designers, Sebastian Herkner, for this year’s Handmade, he arrived at the workshops with something like reverence: ‘Lobmeyr specialises in very precise glass objects,’ says Herkner. ‘Entering their workshops for the first time, observing the craftsmen and discussing our idea and design approach with them had a great impact on me.’ This comes from a designer who has already worked with a broad range of leading manufacturers, including ClassiCon, Pulpo, Moroso and Rosenthal, since founding his own studio in Germany in 2006.

Reputations aside, designers and manufacturers only really develop respect for one another by working together. ‘Projects such as Wallpaper* Handmade are a great opportunity to get to know a designer, to find out if they are compatible for future collaborations,’ says Leonid Rath. ‘I can, of course, just brief a designer because I know other examples of his or her work, but it is completely different when you have actually worked and solved problems together.’

Lobmeyr’s Leonid Rath and Herkner check the vessel's lid fits perfectly. Photography: Lisa Edi

It didn’t take long for Rath to appreciate Herkner’s particular skills when it came to design: ‘Sebastian works very effectively, intervening at exactly the right moments and paying great attention to detail.’ Herkner and Lobmeyr had three months to come up with a finished piece. ‘It was absolutely not much time!’ exclaims Rath, noting that, in his business, timelines of five years are normal. ‘But sometimes working under this kind of pressure can be a good thing.’

‘The project Taking Care of Wild Relatives began with the idea of creating a container for something very special and cherished,’ explains Herkner, ‘and what could be more precious than nature – the basis of our existence?’ Herkner recalled the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway, a bank of crop-seed samples being stored in the Arctic permafrost for future generations. With further research, Herkner’s team realised how urgently climate change is threatening the survival of food crops. Most crops are delicate hybrids sensitive to drought and disease; cross-breeding them with their wilder ancestors creates new hybrids that are able to withstand infections and changing conditions. The most valuable commodities in the world might then be the wild original versions of our essential crops.

Herkner’s team got in touch with the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations for advice, and they sent seeds from the wild relatives of five key crops threatened by climate change – wheat, peanuts, cowpeas, potatoes and oats. ‘I think it is important to highlight things which are super normal for us, but are also in danger of getting lost,’ says Herkner. ‘These five seeds are important for human beings in so many ways, from food to clothing and energy.’

He then designed a set of five handmade glass bell jars to contain these precious seeds. The bottom sections are chunkier, with facetcut pedestals, while the tops are domed and made of much finer glass, with the Latin names of the seeds and illustrations of the plants engraved upon them, reminiscent of old apothecary containers. He then added delicate little silver-plated brass pedestals inside to hold the seeds themselves.

The contrast between the thinner lids and chunkier bases of the glass elements was a great challenge for Lobmeyr, says Rath: ‘A big problem was to stop the rounded top part from jamming onto the bottom section.’ Both were mouth-blown into wooden moulds, but the glass thickness was nevertheless hard to control: ‘The interior form of the upper part, which has to fit on the bottom, was especially difficult, and achievable only through years of experience on the part of the glassblower.’

Compounding the difficulty, the two glass sections had to be made in separate manufactories, located some 500km apart: one for the heavier bases in North Bohemia in the Czech Republic, and another that specialises in finer glasswork near Lake Balaton in Hungary. The coordination of craftsmanship and millimetre precision to make the components to fit exactly was quite extraordinary. ‘You would not believe how perfectly they fitted when put together. They slid over each other like a Japanese tea caddy. Even I was amazed!’ says Rath.

The magic of glass is that, although it is made from one of the most basic, common minerals on the planet, silicon dioxide, it can be transformed into something highly precious by skill alone. ‘This is the essence of it; what we are all about,’ explains Rath. ‘Our biggest challenge over the last 15 years has been to make things that have contemporary value; to discover what uses are valuable to people today, and the rituals of today. It is a really fascinating and beautiful task.’

As originally featured in the August 2017 issue of Wallpaper* (W*221)

Left, a vessel and pedestal. Right, engraving on the cutting wheel

Left, a motif being transferred to the glass. Right, soldering a pedestal

A craftsman working at the copper wheel

Left, a brass pedestal element being polished. Right, a marker pen is used to delineate cut points

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Sebastian Herkner website, Lobmeyr website and FAO website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

First look: Solange Knowles on designing her new glassware collection, ‘Small Matter: Form Glassware 001’ for Saint Heron

First look: Solange Knowles on designing her new glassware collection, ‘Small Matter: Form Glassware 001’ for Saint HeronWe interview Solange Knowles, who tells us about her desire to democratise good design and its power to elevate mundane gestures into ceremonial moments

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Residenza Cappellini combines bold colour and Italian design in Manhattan

Residenza Cappellini combines bold colour and Italian design in ManhattanFrenchcalifornia and Giulio Cappellini present Residenza Cappellini, adding Italian interior flair to the Manhattan skyline

By Tianna Williams

-

Japanese glass artist Baku Takahashi teams up with Trueing to create colourful lamp designs

Japanese glass artist Baku Takahashi teams up with Trueing to create colourful lamp designsSwitched-on lighting and uplifting objects from New York studio Trueing and Japanese glass artist Baku Takahashi

By Pei-Ru Keh

-

Pitch perfect: ‘Love Rocker’, by Owen Bullett Studio and Heerenhuis

Pitch perfect: ‘Love Rocker’, by Owen Bullett Studio and HeerenhuisFor Wallpaper* Handmade X, sculptor Owen Bullett and table manufacturers Heerenhuis devised a rocking chair for two

By Anna Winston

-

Wet set: ‘Three Isles’ birdbaths, by Teo Yang Studio and Huguet

Wet set: ‘Three Isles’ birdbaths, by Teo Yang Studio and HuguetBy Blaire Dessent

-

Marine Julié etches ‘a farandole of bisexual beings’ on Rückl glass

Marine Julié etches ‘a farandole of bisexual beings’ on Rückl glassFor Wallpaper* Handmade X, Switzerland-based artist Marine Julié designed ‘Constellations of Us,’ a collection of vases and cups, with Czech glass maker Rückl

By Rima Sabina Aouf

-

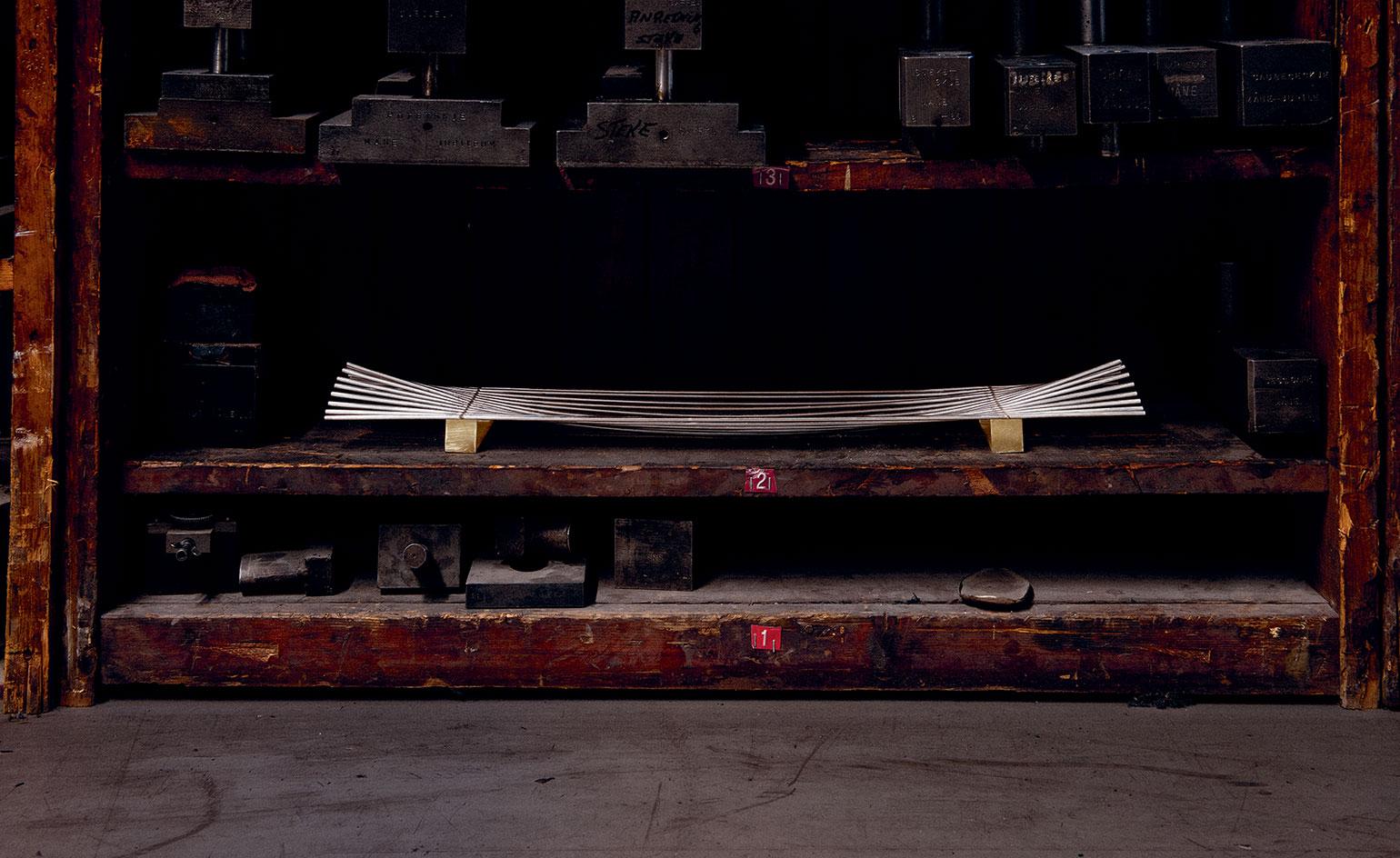

Artisanal precision is at the core of the ‘Arched’ centrepiece

Artisanal precision is at the core of the ‘Arched’ centrepieceFor Wallpaper* Handmade X, Norwegian silver manufacturer Arven and Design Academy Eindhoven graduate Guglielmo Poletti design a seemingly simple ‘conversation piece’

By Rosa Bertoli

-

Lars Beller Fjetland and Bottega Ghianda craft love birds

Lars Beller Fjetland and Bottega Ghianda craft love birdsFor Wallpaper* Handmade X, Norwegian designer Lars Beller Fjetland and Italian workshop Bottega Ghianda translated the romantic symbolism of the duck into ‘Amaranth’, a series of stylised bird figurines

By Rosa Bertoli