Up in Michigan: three Midwest furniture makers conceive the offices of the future

Three Michigan office furniture giants, Haworth, Herman Miller and Steelcase, who have combined sales of $6.7bn in 26 countries, have the offices of the future in the works.

In one way at least, the future of office design most closely resembles its past. For over a century, designers, carpenters, engineers, graphic designers and at least one sculptor, based in factories and studios in and around the otherwise perfectly unremarkable city of Grand Rapids, Michigan, have devised, produced and exported the environment in which many of us spend our daily lives.

First they proselytised in Chicago, then throughout the US, before heading overseas. So successfully have they done this that in 2014, the three Michigan office furniture giants, Haworth, Herman Miller and Steelcase, had combined sales of almost $6.7bn in 26 countries.

Yet some things stay the same. Herman Miller still greets visitors to its Design Yard at the Nelson Room, a beautifully curated selection of some of its greatest hits, almost all planned, designed and built locally. Haworth maintains its primary manufacturing facilities in Holland, Michigan, with its global HQ some 30 minutes down Highway I-196 from Grand Rapids. True, it now also operates plants in Asia and Europe, but it remains committed to developing products by the shores of Lake Michigan before manufacturing them in local markets.

Michigan is where the suspension filing cabinet, the ‘Aeron’ chair and of course the cubicle came from. Michigan is where the ideas keep coming from. The paradigm for this process is research. The team at Steelcase turned to neuroscientists to help design its latest award-winning Brody range. ‘To be human is to be distracted. We’re not undisciplined or scatterbrained. We’re overwhelmed,’ explains Markus McKenna, the company’s design director. These local experts helped the firm plan solutions to the global problem that nowadays workers switch tasks every three minutes, get interrupted every 11 minutes and take 23 minutes to get back into the swing of work.

When graphic artist Robert Propst devised the Action Office for Herman Miller in 1968, he was reacting to a US office environment he called ‘a wasteland’. ‘It saps vitality, blocks talent, frustrates accomplishment. It is the daily scene of unfulfilled intentions and failed effort,’ he wrote. His solution became known – often in a rather debased form – as the cubicle. The original design included acres of work surfaces and display shelves; partitions were just a part of it, intended to provide privacy and places to pin up works in process. The Action Office even included varying desk levels to enable employees to work part of the time standing up, encouraging blood flow and staving off exhaustion. He was answering, in short, many of the same questions his successors are grappling with today. Given the way the world of work is changing, how should the office evolve?

Today, this question seems every bit as urgent as it did then. How should the office change when entrepreneurs now work as happily from the hotel lobby as they do an airport lounge; when smartphones are the first thing many people touch when they wake in the morning, and the last thing they touch at night. What relevance does the traditional desk chair and filing cabinet combo have anymore? The working day is no longer nine-to-five, and the workplace is no longer restricted to an actual place of work. So how should we define the office now?

Ryan Anderson is director of product strategy at Herman Miller; exploring the future of office working is his remit. ‘There is a fundamental shift happening in the modern office,’ he says. ‘Today’s offices are being designed with a wide variety of spaces to be shared by everyone. This is in great contrast to most spaces that exist today that are filled with a uniform collection of individual cubicles [in the US model] and private offices.’

The old methods of space planning – that sea of sameness emblematic of offices in the 1980s and 1990s – were based upon a simple assumption that most people could do a majority of their activities by themselves, in a single space, explains Anderson. ‘To some extent this was true because the technologies we used were fixed in that space. Each person had a desk, a chair, a computer and a phone. And it wasn’t easy to move from that location and remain productive.’

The modern business person is no longer so shackled. Workplace studies show that ‘desk utilisation’ is often below 60 per cent. This means 40 per cent of the time or more it might only be safekeeping a computer, with nobody actually there. The new assumption is that there is no single place within an office that can support the entire range of work activities for any person on a given day, says Anderson. ‘Instead, offices are becoming like homes where each person may have their own space, but those are supplemented by a wide variety of spaces to chat with a co-worker, co-create with a group, or contemplate individually about an important decision.’ Herman Miller has renamed this varied office landscape a ‘Living Office’.

The company has created a framework of these types of space arrangements so customers can get a feel for what is possible beyond the individual workstation. And crucially, given the increased squeeze on personal real estate in offices, the mobile worker model is actually a space saver. ‘Since the demands on the individual spaces are fewer, the mix of spaces can often shift within the same (or even less) overall real estate.’

The knowledge economy is increasingly made up of freelancers, micro-businesses and remote workers. And many of them are doing their business in new-model shared workspaces. WeWork, now a global phenomenon, has about 3.5 million sq ft of co-working office space in a dozen cities, and is valued at over $5bn – $1.5bn more than Regus, the 20-year old veteran of the serviced office industry, with 3,000 offices in 120 countries. With new players joining the co-working market on a seemingly daily basis, it’s not something that office place-makers can afford to ignore. Even Soho House, the bastion of the private members’ club, recently announced it was to open several co-working spaces under the Housework brand, starting with London, Chicago, Los Angeles and Istanbul.

The key lesson to be learned from the success of these spaces is how well they are able to support interaction and collaboration. Doug Sitzes, senior workplace strategist at Haworth, explains: ‘The users of these spaces are usually individuals looking for affinity with like-minded people. Their intent is to share information, expertise and contacts. Otherwise, they could just work at home.’

The traditional open-plan office can be redesigned to meet all three of those needs, but to be truly successful it needs areas where people can focus on their work, areas where they can meet formally and collaborate creatively, as and when they need to. To look at it another way, workplaces are becoming more urban in their design. ‘I see them almost as cityscapes that are sometimes residential, sometimes outdoor, sometimes all business, sometimes all collaboration,’ says Sitzes.

Co-working and start-up culture, and a kind of domestication of the workspace, have also driven the residential furniture companies to move into the office furniture landscape. Start-ups that don’t want to be seen as stuffy, or corporate, are demanding one-of designs and DIY aesthetics. Of course, a more homely, colourfully upholstered, relaxed look and feel is no longer enough. There is a new focus on wellbeing, as well as interest in innovation areas and ‘focus nooks’ too, adds Sitzes. ‘Really, anything that will help workers be their best is being looked at.’

The maxim at Herman Miller is that ‘Workers are shoppers’. What makes a space right for someone is a complex mixture of the work they are doing, their dependence upon others, personal work style, and so on. Lori Gee, the brand’s vice-president of applied place-making, says uniform work culture is a thing of the past: ‘The incorporation of more colour and comfort into workplaces continues. This is part of offering a variety of spaces within the office landscape, akin to what you would find in a home. What we are exploring next is how to create idealised settings that align the surroundings, furnishings and tools to best support different types of work.’ This has led to new ranges such as Exclave, performance tools for collaboration spaces; Metaform Portfolio, which allows users to tailor an area in the moment to suit their needs; and a series of performance work stools (‘Sayl’, ‘Mirra’ and ‘Caper’) to support better interactions during presentations, as well as enabling people to sit at standing height work surfaces, which allows for more varied postures while working.

We are not seeing a move away from open plan offices, says Gee, but towards open plans that offer diverse settings to support an array of ways to work. Sitzes agrees. ‘There are still people who say, “We want to be like Google”, but that is a paradigm that even Google is shifting way from with their new campus development. Spaces are becoming more people-centric, actually allowing workers to flourish as part of something bigger. We are seeing the open office and sea of cubes concepts shift to free-range collaboration.’

Ultimately, an office today is a place that enables people to do their very best work, an ecosystem that offers a more productive working environment – one that people not only are able to work in efficiently, but will choose to, over and above their kitchen table, members’ club or beach. Campus culture is one symptom of that. Co-working is another. The home office yet another. None is the perfect solution for everyone, or a one-size-fits-all answer – and that, according to Michigan’s finest, is precisely the point.

As originally featured in the November 2015 issue of Wallpaper* (W*200)

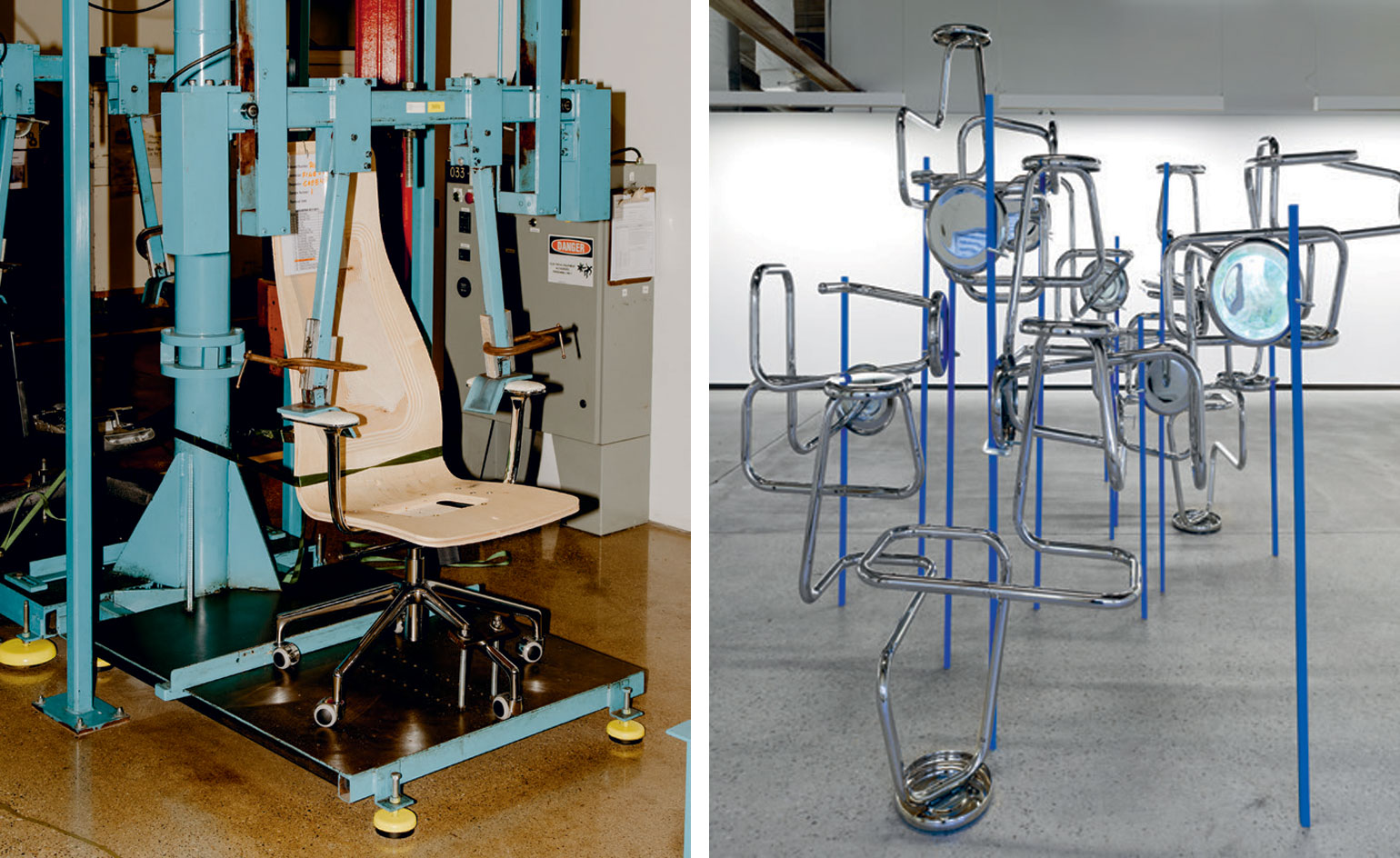

Left: Jasper Morrison’s ’Lotus’ chair being tested in the Haworth lab. Right: Molecule, by Michel de Broin. Wallpaper* commissioned the Canadian artist to create a sculpture based on Haworth’s ’K700’ tubular metal stools for the cover of our Officepaper* supplement (W*200)

Patricia Urquiola’s ’Openest’ series for Haworth

Left: the performance seating wall at the Herman Miller Learning Plant, featuring models such as the ’Embody’, ’Mirra’ and ’Sayl’ chairs. Right: its Metaform portfolio line includes colourful metal screens and shelves

Herman Miller’s Nelson Room features some of the company’s greatest hits, including Alexander Girard’s ’Alphabet’ wallpaper; Charles and Ray Eames’ plywood lounge chairs and Isamu Noguchi’s coffee table

INFORMATION

Photography: Ryan Lowry

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Henrietta Thompson is a London-based writer, curator, and consultant specialising in design, art and interiors. A longstanding contributor and editor at Wallpaper*, she has spent over 20 years exploring the transformative power of creativity and design on the way we live. She is the author of several books including The Art of Timeless Spaces, and has worked with some of the world’s leading luxury brands, as well as curating major cultural initiatives and design showcases around the world.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti