Can design help us better understand the future?

Yosuke Ushigome, the self-styled ‘creative technologist’ and director at design studio Takram on the power of speculative design to make ideas tangible, humanise big data, and encourage healthier behaviours

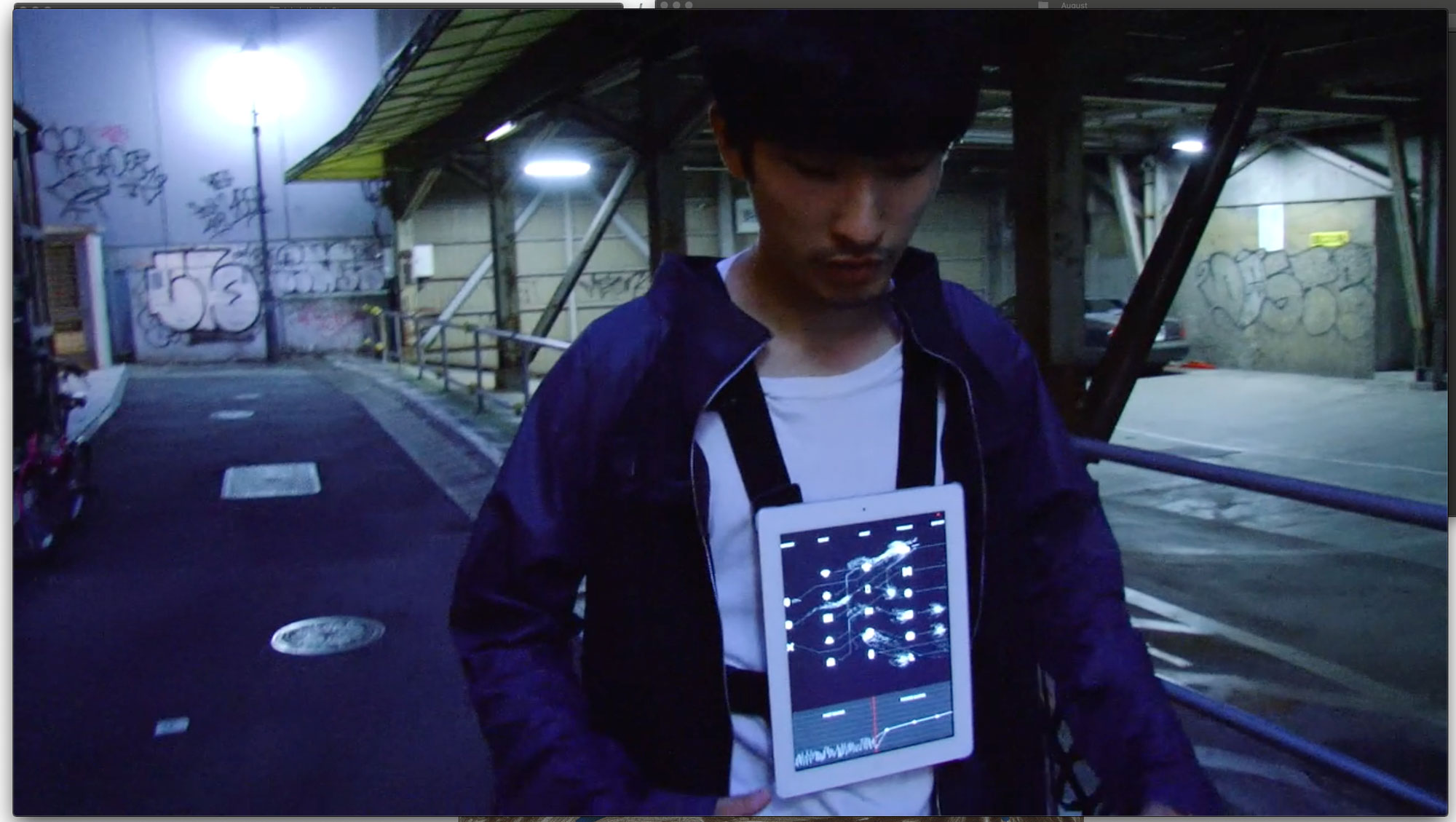

When I first saw Yosuke Ushigome, now director at Takram's London office, he was part of an exhibition at Tokyo's 21_21 Design Sight in 2015. In a video titled Professional Sharing, Ushigome wears a homemade jacket with solar panels and pockets for various digital devices. He walks around Shibuya, as per requests from real-time clients, and gets paid for taking specific pictures at specific locations. Sometime during the video, he takes an online break while lending his devices’ processing powers to someone mining a digital currency. Later he queues up at a popular restaurant on someone else’s behalf, and likewise gets paid for his time. It was the sharing economy taken to the extreme, and a peek into the not-too-distant future, as he saw it at the time.

Yosuke Ushigome, creative technologist

Still from Professional Sharing

Ushigome calls himself a creative technologist. He studied system design engineering and later mechano-informatics in Tokyo before doing a master’s in design interactions at the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London. ‘I wanted to be better at communicating technological and engineering ideas from a more humanistic perspective,’ he explains. He studied under Critical Design pioneers Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, and has been working in design and technology ever since. ‘I believe in the power of design to make ideas tangible – not to make you buy more, but to make you think.’

After graduating from the RCA, he freelanced and worked briefly at design studio Superflux in London before Takram approached him (and fellow RCA alumni Miles Pennington and Lukas Franciszkiewicz) in 2014 to help start its London office.

I believe in the power of design to make ideas tangible – not to make you buy more, but to make you think

Today, Ushigome continues to spend much of his time visualising and speculating on what the future might look like. ‘Takram started out as a company trying to bridge design and engineering, but today we do more work helping our clients define their vision,’ Ushigome explains over Zoom.

Heavy Load, a speculative project by Takram featuring an automatic toileting device designed for an exhibition at the Museo Della Merda, Italy

With about 40 people in Tokyo, four in London and two in New York, Takram is the first Japanese design innovation studio to go fully global. Its services include branding, product and service design, and what it calls ‘future vision design proposals’. It’s not always easy to put one’s finger on exactly what the company does. Scrolling through its website doesn’t necessarily make it all that much clearer: there is a project featuring a cute-looking agricultural robot; a couple of branding projects for a small fruit farm in Hokkaido and Japan’s largest online flea-market platform Mercari; and also, what on the homepage is described as a ‘speculative design proposal for an automatic toileting system’, adequately named Heavy Load.

Design is what ties all of these seemingly very different projects together. ‘We really believe in the power of design, and design as part of research,’ explains Ushigome, who works on most of Takram’s more speculative and futuristic projects. Professional Sharing is a good example of how the company uses design to try and suggest what the future might look like. By realising and showcasing their visions, the designers encourage stakeholders and the public at large to think about what can lie ahead.

Humanising big data

The RISAR app aims to humanise data by using augmented reality to personalise the effects of climate change

Another example of using design to try and engage people to think more about the future is the RISAR prototype app, presented at the 2020 Design Indaba conference in Cape Town. On the app, people are asked simple questions that have a direct effect on the rising sea levels, like how they commute to work. Depending on their choices and their physical location, the app predicts and demonstrates how they might experience the rise of sea levels.

Using a phone camera and augmented reality technology, users can see the virtual sea rise right in their living room or in the park if they make environmentally irresponsible decisions. ‘Of course, this is all a bit oversimplified, but I think it’s a great way of humanising big data,’ Ushigome says. It’s a simple but powerful way of explaining something as complex as climate change; the amount of publicly available data on such phenomena can be overwhelming and difficult to relate to everyday life, but seeing your kitchen slowly fill up with water because you consistently take the car rather than ride a bicycle to work drives the issue home.

Data is only useful and relevant if understood, and design can be an excellent tool in making it so

Such self-initiated projects often generate quite a bit of interest, which in turn helps Takram expand its service portfolio. Sometimes these projects are fully self-funded, other times Takram might approach another company with an idea, in the hope of collaboration and funding opportunities. Companies and government agencies also contact Takram for specific projects, such as the prototype Regional Economy Society Analysing System (RESAS) developed for the Japanese government in 2015. RESAS is a web-based system that gives clear and visually pleasing representations of nationwide data on topics such as population, economics, tourism and consumption, sourced from Japan’s central Teikoku Databank. It is used today by policymakers throughout the country to make sense of phenomena such as the movement of people or goods within and across different prefectures, or the change in economic growth in one area compared to another. It is another example of what Ushigome likes to refer to as the humanisation of data. ‘Data is only useful and relevant if understood, and design can be an excellent tool in making it so,’ he says.

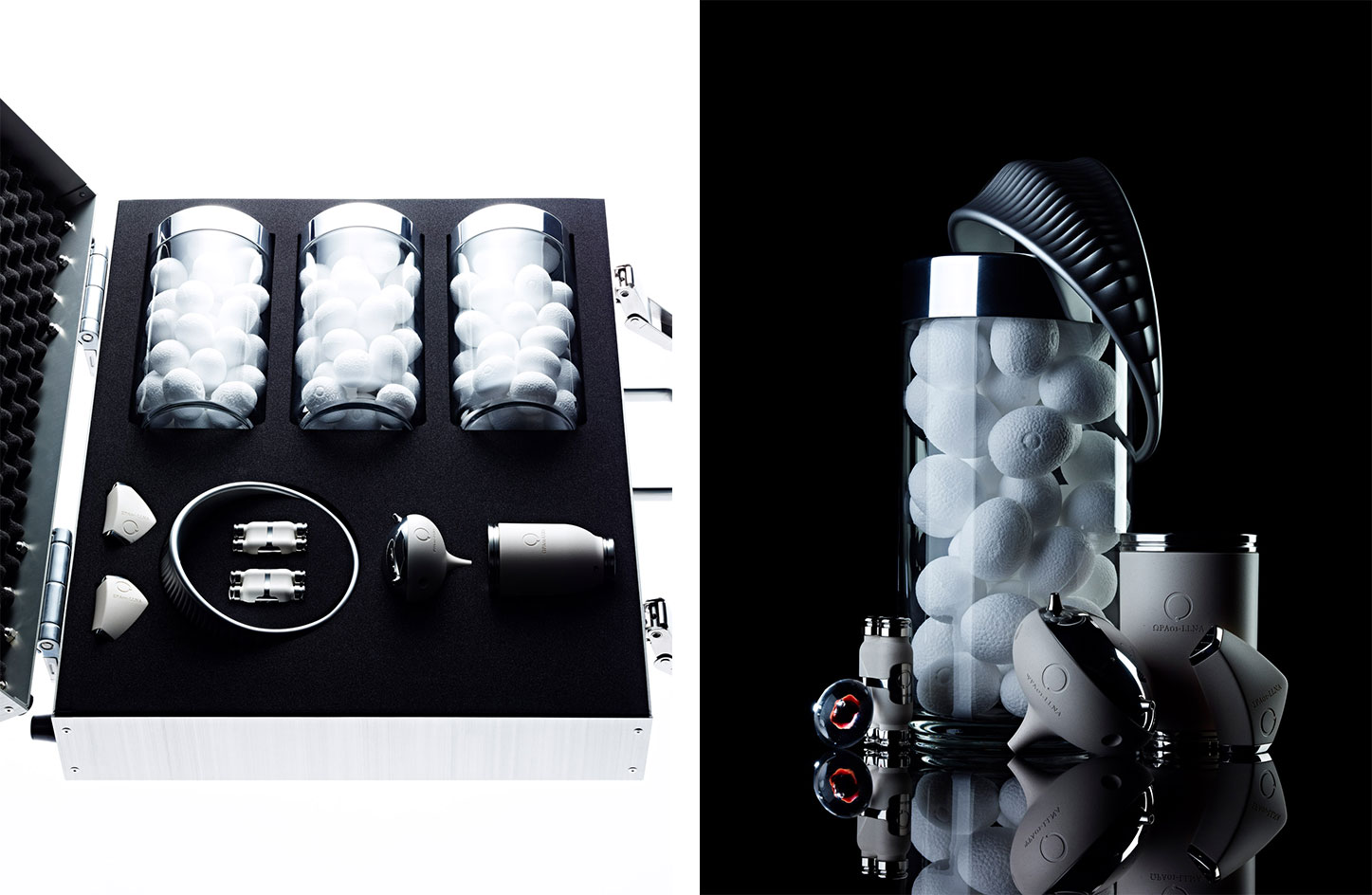

Takram’s speculative designs include the Shenu Hydrolemic System, a series of artificial organs designed to conserve water inside the human body, created for an exhibition at Documenta

Over the last 18 months, Takram has been working together with Hitachi’s Research & Development Group to create a website, sustainability-transitions.com, to share ideas for building a more sustainable world in small increments, or ‘transitions’. It features key findings from interviews with 12 leaders in sustainability, from Jonelle Simunich, a senior foresight strategist at Arup, to Yuji Yoshimura, a professor at the Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology at the University of Tokyo. ‘Thinking in transitions can give us a much fuller picture of how we build a sustainable future,’ it reads. ‘And it gives us practical, concrete steps we can take to help get us there.’

The website proposes ten transitions, including Centralised to Distributed, Degenerative to Regenerative, and Fossil to Renewable, and explains why they are necessary to build a sustainable future. It outlines opposing sets of qualities that define the current world (which sees energy as a resource, gradually running out while polluting the environment) and a preferable world (energy as a flow, renewably supplied and non-destructive). Importantly, it also offers very concrete proposals as to what each individual can do to help these transitional changes.

‘I think that with Covid, being able to highlight and facilitate these kinds of discussions about the future is perhaps more important than ever,’ Ushigome says. He goes on to explain that, if anything, Takram has received more enquiries because of the pandemic. Perhaps clients are more willing to entertain speculative design proposals in uncertain times such as these? Takram and Ushigome might not have all the answers, but their innovative and forward-looking approach is sure to make you stop and think.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

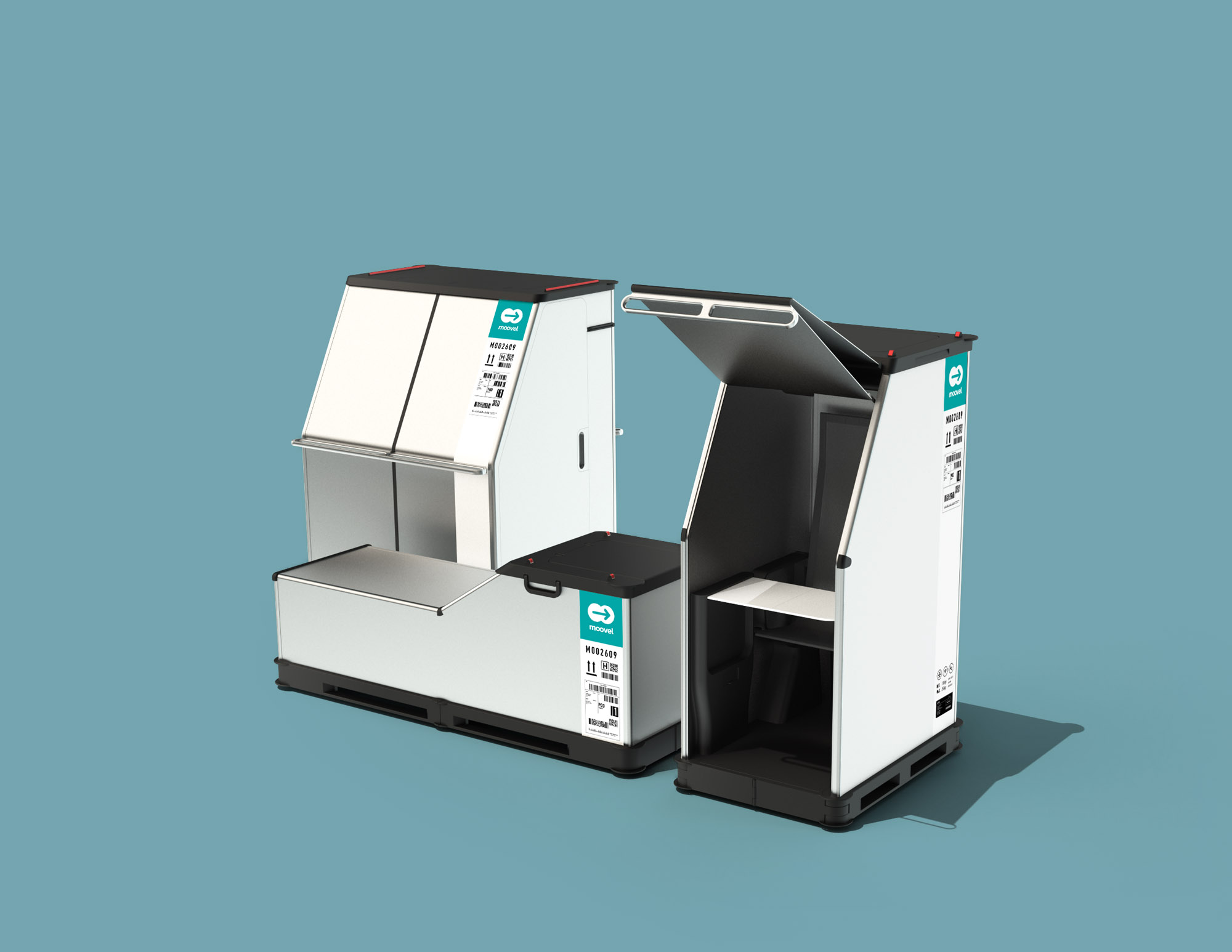

Another of Takram’s speculative designs, this Personal Mobility Pod for Moovel Lab would allow you to ship yourself using existing infrastructure

Home Shrine, a project for Swarovski, explores our relationship with virtual assistants

INFORMATION

Originally from Denmark, Jens H. Jensen has been calling Japan his home for almost two decades. Since 2014 he has worked with Wallpaper* as the Japan Editor. His main interests are architecture, crafts and design. Besides writing and editing, he consults numerous business in Japan and beyond and designs and build retail, residential and moving (read: vans) interiors.

-

The Bombardier Global 8000 flies faster and higher to make the most of your time in the air

The Bombardier Global 8000 flies faster and higher to make the most of your time in the airA wellness machine with wings: Bombardier’s new Global 8000 isn’t quite a spa in the sky, but the Canadian manufacturer reckons its flagship business jet will give your health a boost

-

A former fisherman’s cottage in Brittany is transformed by a new timber extension

A former fisherman’s cottage in Brittany is transformed by a new timber extensionParis-based architects A-platz have woven new elements into the stone fabric of this traditional Breton cottage

-

New York's members-only boom shows no sign of stopping – and it's about to get even more niche

New York's members-only boom shows no sign of stopping – and it's about to get even more nicheFrom bathing clubs to listening bars, gatekeeping is back in a big way. Here's what's driving the wave of exclusivity

-

Pentatonic and Natalia Vodianova launch innovative face mask

Pentatonic and Natalia Vodianova launch innovative face maskNatalia Vodianova and Pentatonic unveil Masuku one, their new high-tech, sustainable mask design featuring state of the art filtration system and made in England

-

Portable handwashing station wins Life-Enhancer of the Year: Wallpaper* Design Awards 2021

Portable handwashing station wins Life-Enhancer of the Year: Wallpaper* Design Awards 2021Responding swiftly to a public health emergency, Lagos designer Nifemi Marcus-Bello devised a portable, modular handwashing station that draws on local materials and manufacturing expertise

-

Sarah Douglas rewinds a very different year of design at Wallpaper*

Sarah Douglas rewinds a very different year of design at Wallpaper*Wallpaper’s Editor-in-Chief looks back on her favourite editorial moments from 2020 – a year when the design world could have stood still, but kept turning, powered by its incredible community

-

Mark Dalton on helping people navigate a pandemic through design

Mark Dalton on helping people navigate a pandemic through designDesign Emergency began as an Instagram Live series during the Covid-19 pandemic and is now becoming a wake-up call to the world, and compelling evidence of the power of design to effect radical and far-reaching change. Co-founders Paola Antonelli and Alice Rawsthorn took over the October 2020 issue of Wallpaper* – available to download free here – to present stories of design’s new purpose and promise. Here, Alice Rawsthorn talks to creative director Mark Dalton

-

Architect Michael Murphy on designing healthcare systems

Architect Michael Murphy on designing healthcare systemsDesign Emergency began as an Instagram Live series during the Covid-19 pandemic and is now becoming a wake-up call to the world, and compelling evidence of the power of design to effect radical and far-reaching change. Co-founders Paola Antonelli and Alice Rawsthorn took over the October 2020 issue of Wallpaper* to present stories of design’s new purpose and promise. Here, Paola Antonelli talks to architect Michael Murphy

-

Wallpaper* and AHEC announce a new initiative to support design’s next generation

Wallpaper* and AHEC announce a new initiative to support design’s next generationDesigners will be offered a platform to conceive, create and manufacture a new piece of furniture or object inspired by life in a pandemic world

-

Paola Antonelli and Alice Rawsthorn on design as a powerful tool of change

Paola Antonelli and Alice Rawsthorn on design as a powerful tool of changeDesign Emergency began as an Instagram Live series during the Covid-19 pandemic and is now becoming a wake-up call to the world, and compelling evidence of the power of design to effect radical and far-reaching change. Co-founders Paola Antonelli and Alice Rawsthorn took over the October 2020 issue of Wallpaper* – available to download free here – to present stories of design’s new purpose and promise

-

Artist-designed face masks raise money for Covid-19 relief efforts

Artist-designed face masks raise money for Covid-19 relief effortsFace masks are here to stay – for now – and so their functional purpose is developing into another form of self-expression