Biotech perfume brand Abel thinks fungus, yeast and sugar are the future of fragrance

Abel is starting a biotech revolution in the world of perfume, Laura Feinstein discovers

Founder of Abel, Frances Shoemack, is on a mission to revolutionise the perfume industry. The New Zealand-based brand is one of the first perfume houses to eschew synthetic ingredients (many derived from fossil fuels) for cutting-edge biotech that combines molecules from natural sources. This includes plant sugars, yeast, bacteria, and even fungi to create scalable, entirely organic scents with a powerful dry down.

Shoemack, who is a former winemaker, started Abel ten years ago during a time when ‘clean beauty’ was a rising buzzword for the mainstream cosmetics industry. Broadly speaking, this umbrella term is used when referring to products containing naturally derived ingredients in place of chemicals that can be harmful to the body and the environment. (Some synthetic ingredients have been found to build up in drinking water, food and even human tissue.)

Abel uses biotechnology to create perfume

Today's consumers are more likely to spot the warning signs of ‘greenwashing’ from brands a mile off. (We now expect much more than a smattering of organic ingredients and a ‘non-toxic’ label slapped on the front of a bottle.) But this duplicitous marketing practice is – and has always been – worlds away from the pioneering production methods at the heart of Abel.

Keen to conceptualise a genuinely organic perfume line from the get-go, Shoemack sought out fellow New Zealander and master perfumer Isaac Sinclair (who has previously worked with the likes of L’Occitane) and Fanny Grau, a Paris-based nose with a doctorate in chemistry. The brand first gained a following with its organic room sprays, which are entirely crafted from essential oils and plant-derived compounds, without the need for synthetics, sulfates, or parabens. However, advancements in biotech have broadened the brand’s palette, enabling it to compete with synthetic scents when it comes to longevity and complexity.

‘We continue to use natural ingredients and essential oils alongside biotech ingredients because of the dynamism, beauty, and richness they provide,’ Shoemack tells Wallpaper*. ‘However, biotech allows us to control the process and switch to a lower impact molecule if we have concerns over supply, or want molecules that don't exist organically in nature.’ Shoemack explains that this has opened up a world of creative possibility: ‘With our first fragrances, if someone was only working with plant-derived ingredients, it [limited] the full scent palette of five or six thousand [notes] to 50 or 60.’

Abel's latest Eau de Parfum, ‘Laundry Day’, is its most advanced scent yet, made almost entirely with renewable and biodegradable technology. It is described as a ‘verdant, sun-filled citrus’, with vetiver, lime and passionfruit notes derived directly from the fruit’s skin and materials left over from the drink industry. A ‘biotech aldehyde’ (which naturally occurs in alcoholic components of fruits, vegetables, nuts and spices) evokes freshly washed linens, whilst a ‘biotech molecule’ (extracted from plants and known as ‘leaf alcohol’) is responsible for the aroma of freshly cut grass.

‘Guerlain first used [the synthetic molecule] Phenol in perfume over a hundred years ago, but it was considered a novelty, and more expensive than, say, natural vanilla extract,’ Issac Sinclair explains. ‘But today, synthetic vanilla is cheaper than the real thing,’ he continues, noting that limits to mass production have kept many brands from exploring biotech’s full potential.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘When we started Abel, I had to work from scratch. All the rules of traditional perfumery didn’t apply. We never had natural fruit in perfumery before, just different molecules that ended up smelling like passionfruit. Now, we have the real thing and the advancements to make it.’ One such advancement is ‘Garden Labs’ technology (launched by German flavour and fragrance conglomerate Symrise in 2020), which he has used to turn upcycled artichoke from the food industry into a scent profile. ‘We can also use leaks, onions, garlic,’ Sinclair continues. ‘All this crazy stuff.’

Abel founder Frances Shoemack and master perfumer Isaac Sinclair in Tokyo

There may still be a way to go when it comes to larger perfume houses adopting these processes as standard. As Sinclair says, creating perfumes that are 100 per cent organic is more complicated (and much more expensive) than traditional routes. But thanks to the ever-mounting pressure on beauty brands to improve sustainable practices, this could come sooner than we think.

Abel’s ultimate goal is to make ‘every aspect of the brand – from the molecules to the packaging – entirely sustainable’. (It has already segued from a ‘bioplastic’ bottle cap to a fully compostable ‘biotech’ one and is currently working on a limited-edition collaboration with a high-end glassworks studio set for the end of 2024).

A photo posted by on

‘You always have the innovators, the early adopters,’ adds Sinclair. ‘The bigger companies will eventually be doing this. But they’re just not leading the way yet.’

Abel is currently available at Ssense, Stele, Fragrantica and on abelfragrance.com.

Laura Feinstein is a Brooklyn-based writer who has spent almost two decades covering design, technology, and global culture for publications such as The New York Times, The Guardian, Departures, CityLab and The Creators Project at VICE.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

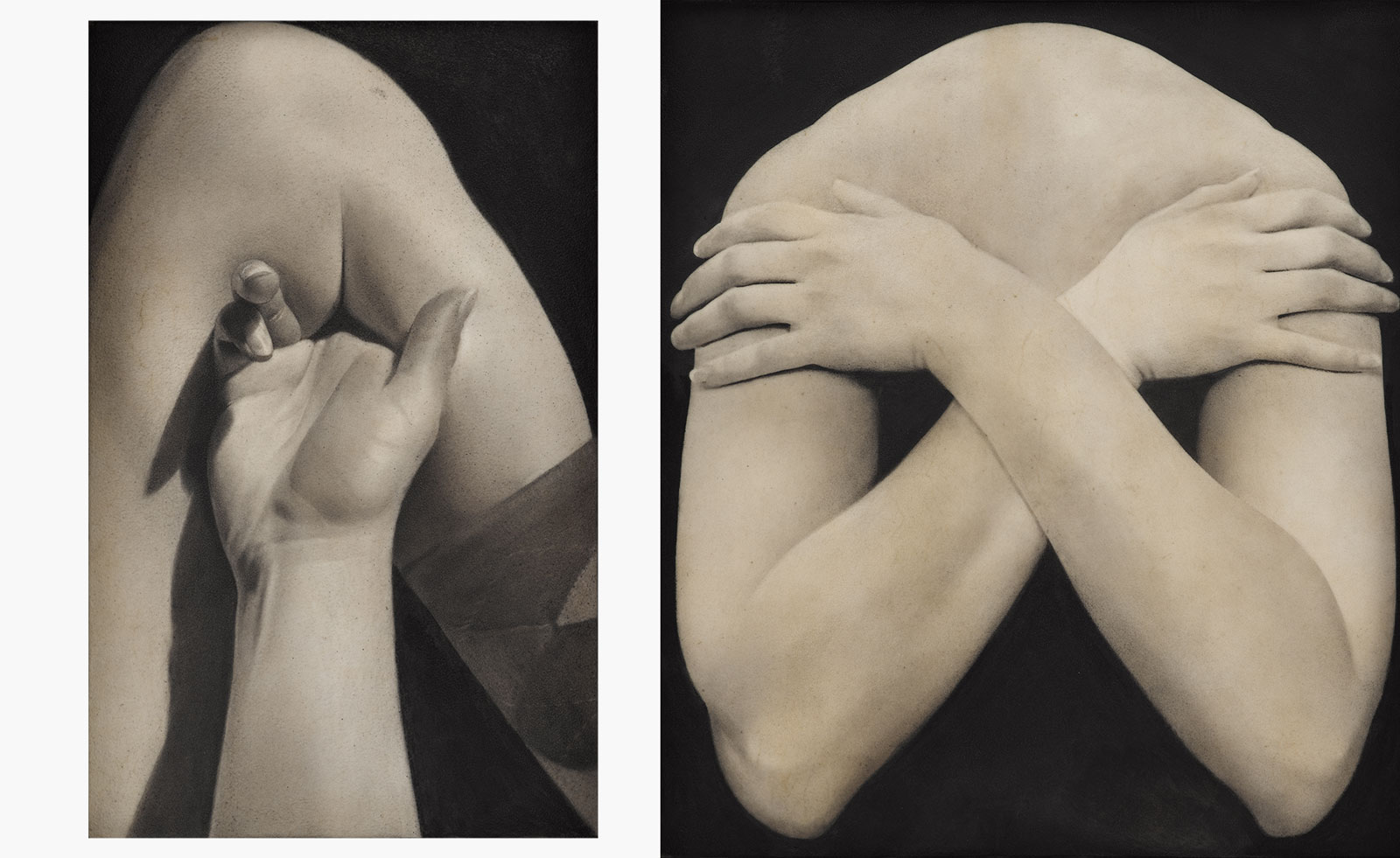

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss