‘Bring No Clothes’: Charleston exhibition undresses the myths surrounding the Bloomsbury group

At Charleston’s new Lewes gallery, curator Charlie Porter uses clothing as a way to retell stories about the Bloomsbury group and its radical protagonists – from Virginia Woolf to Duncan Grant

The writer and curator Charlie Porter likens his latest exhibition – ‘Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and Fashion’ – to ‘turning Charleston upside down and shaking it’, as if to see what falls out.

Charleston is the much-mythologised countryside residence of Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, two protagonists of the early-20th-century Bloomsbury Group, a set of primarily upper-class artists and thinkers whose bohemian, free-spirited approach to art and sexuality signalled an abandonment of restrictive Victorian social mores. The historic farmhouse – purchased by the couple in 1916 – would become a haven for the set outside of London, imagining alternative ways of living amid the evocatively muralled interiors and Edenic gardens (the latter designed by art critic Roger Fry in 1918).

‘Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and Fashion’ and Charleston in Lewes

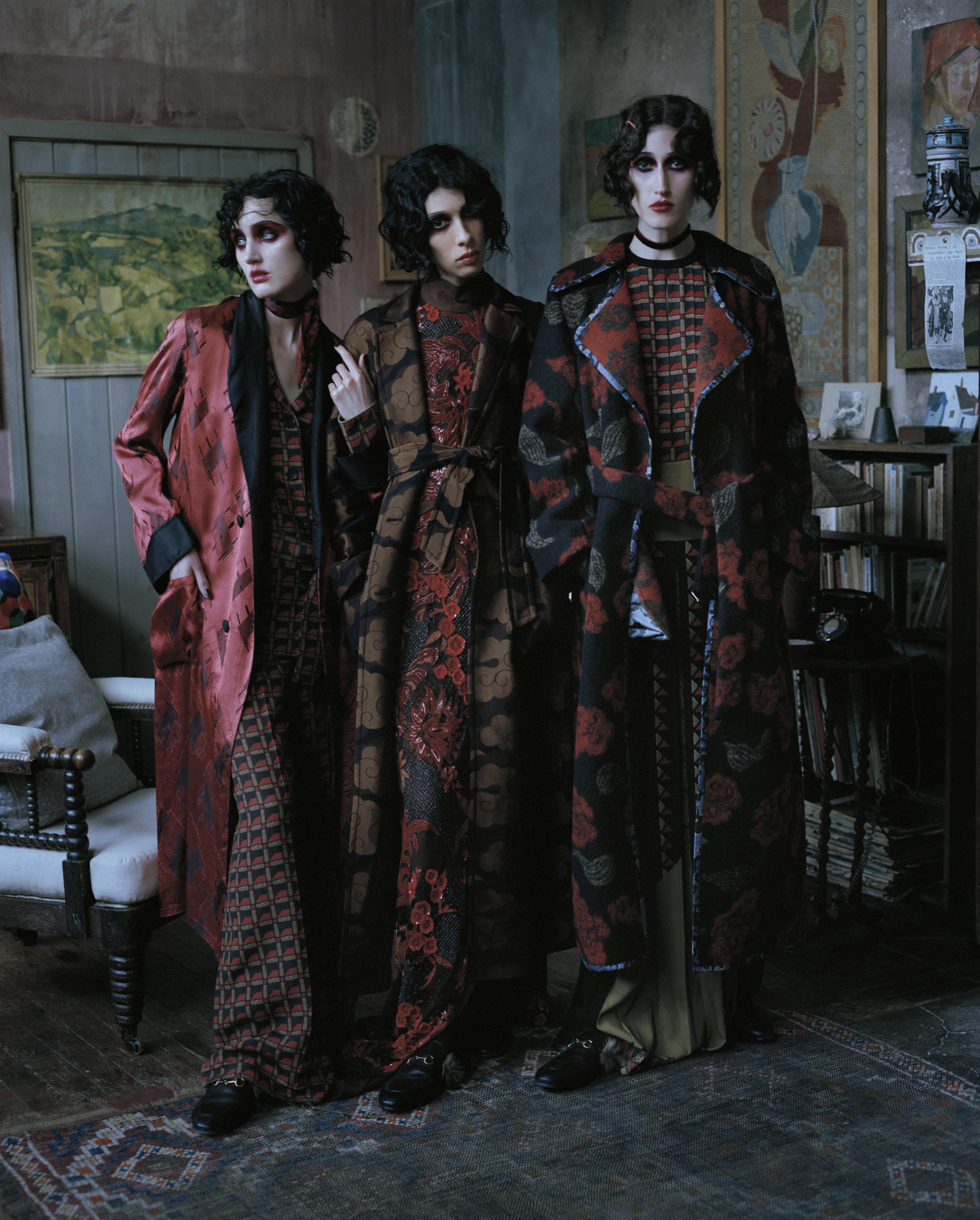

Christina Carey, Jamie Bochert and Anna Cleveland in 'Rebel Riders' from a 2015 Italian Vogue photo shoot inspired by – and shot at – Charleston

‘Bring No Clothes’, though, takes place at Charleston’s latest outpost, a multi-use gallery in the nearby Lewes town centre (titled ‘Charleston in Lewes’, it also hosts a shop, café and a programme of learning and artist-led events). Formerly the district council offices, the stripped-away, industrial interior provides an apt setting for Porter’s contemporary reassessment of the group through their use of, and influence on, fashion. Here, he feels unencumbered by the weighty cultural history of the house and its residents, which have spawned endless films, television programmes and literary representations, as well as plenty of gossip and speculation.

‘I wanted to turn the volume down,’ says Porter at a preview of the exhibition. ‘Most of the Bloomsbury story is told through gossip. And it seemed to me that it was often through men who shouted a lot. Their voices became the ones to tell the story. It’s like: what bubbles up when you turn down the gossip and treat them seriously as individuals? Let’s look at them as young people, young queer people, trying to live and love in a society that doesn’t want them to.’

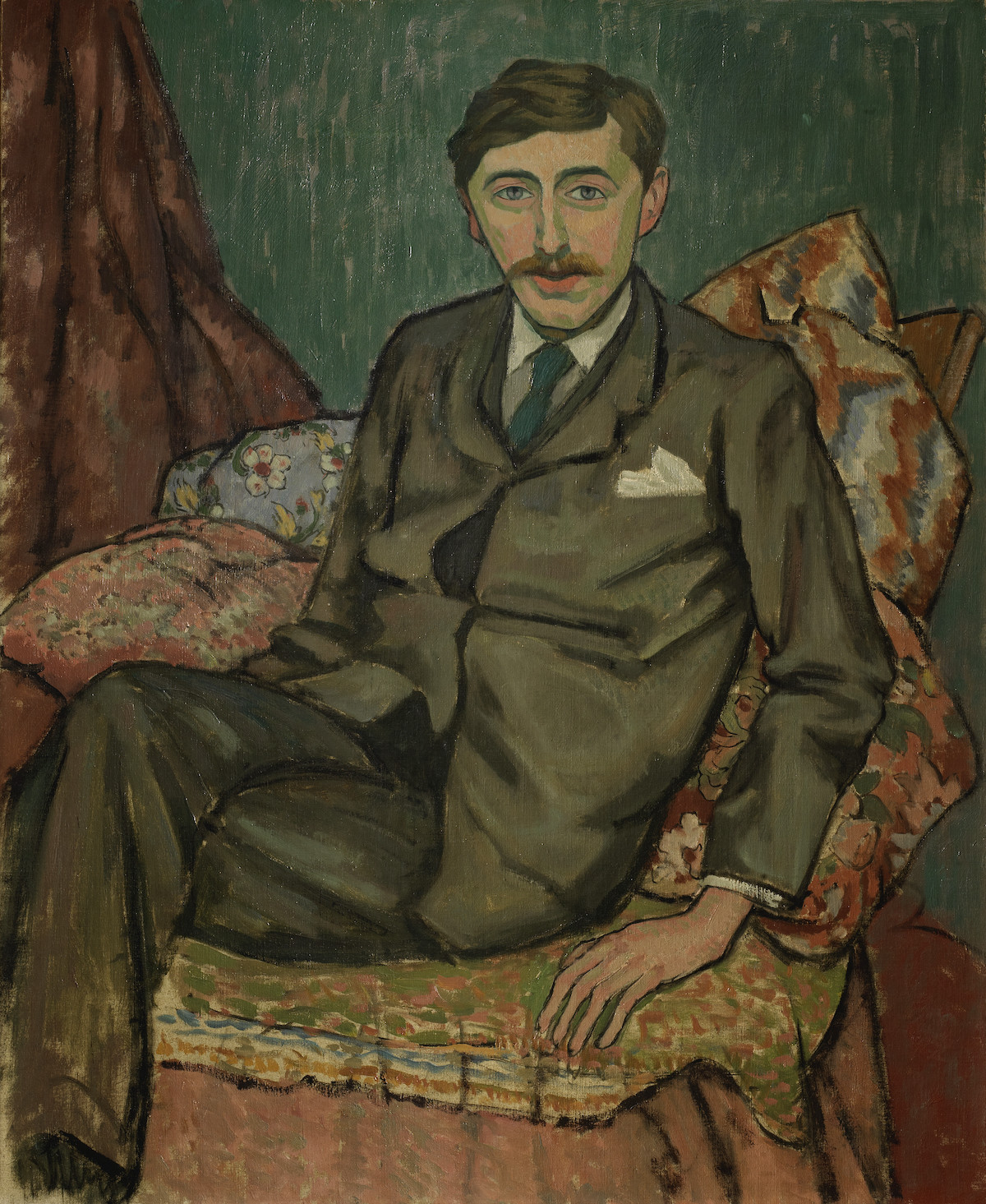

A portrait of EM Forster, one of the protagonists of the exhibition, by Roger Fry, 1911. Private collection

In an echo of his recent book Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and the Philosophy of Fashion – published by Penguin’s Particular Books imprint and a sequel of sorts to his 2021 book What Artists Wear – the exhibition centres on six protagonists and their personal wardrobes. These include Bell and Grant, who both worked as artists, Bell’s sister Virginia Woolf, the author EM Forster, economist John Maynard Keynes and Lady Ottoline Morrell, an aristocrat and prolific hostess. ’I find that when I do this kind of work, writing about people and their clothes, when you focus on their clothes you feel like you are with them,’ Porter says. ‘When you’re looking at their clothes, these other stories emerge. It’s like a Magic Eye picture – when you stare at it long enough suddenly something appears.’

He does so through literary extracts (Woolf’s musings on fashion, across various novels and writings are read in a recording by poet Victoria Adukwei Bulley that plays over the exhibition), paintings, diaries and photographs, which capture the group’s use of – and indeed fascination with – clothing, despite very few material garments appearing in the exhibition as little survived the era (Porter says he’s fascinated by the idea of ‘absence’ when it comes to his curatorial work). As such, the garments on show are primarily contemporary – among them works by Rei Kawakubo, Erdem Moratolgiou, and Kim Jones – scattered throughout and providing a refraction of the historic objects on display and displaying the group’s vast influence on fashion.

Constance Hauman and Kate Lindsey in Olga Neuwirth’s ‘Orlando’ (based on the novel by Virginia Woolf) at the Vienna State Opera, December 2019. Designed by Comme des Garçons, Rei Kawakubo

Two other fashion designers, London-based Jawara Alleyne – who was born in Jamaica and grew up in the Cayman Islands – and Finland-born Ella Boucht, were asked by Porter to respond to the issue’s themes. The former created totemic sculptures comprised of torn-up T-shirts and safety pins, as well as a charred canvas and column (in part inspired by a diary extract from Bell’s housekeeper, who briefly documents burning the artist’s mattress and clothes just after her death), the latter a series of black and white garments designed, much like the rest of their output, with non-binary, trans and gender nonconforming bodies in mind.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The exhibition’s title, ‘Bring No Clothes’, is derived from a 1920 letter from Woolf to TS Eliot, an expression that Porter believes gets to the crux of the Bloomsbury group’s relationship with fashion. ‘Please bring no clothes: we live in a state of utter simplicity,’ she wrote, organising Eliot’s arrival at Monk House, Woolf’s home in East Sussex. In the accompanying book, Porter notes such an expression was found throughout the group’s correspondences, and for him ‘represents a seismic social shift’. ’By clothes, Woolf meant the traditional fashions of her Victorian upbringing... an oppressive word codified by garments.’

Vanessa Bell in a Red Headscarf by Duncan Grant c. 1917, The Charleston Trust

Such trappings were largely abandoned by the Bloomsbury group – dresses became looser, without internal construction or corsetry – a move from restriction that Porter says is particularly potent for Bell and Woolf, whose abusive half-brother Gerald Duckworth would force them into restrictive, corseted gowns and parade them in society as young women. In the then-rundown Bloomsbury, and later Charleston, they found escape.

Indeed, the idea of modernity runs through the exhibition and is no doubt the reason for the continuing fascination with the Bloomsbury set. Theirs was a contemporary way of living that chafed against ebbing Victorian values: Bell would have what we might deem now an open marriage, marrying Clive Bell and living largely independently. Bell would live mostly in Charleston, alongside Grant, her lover (they would have a child, Angelica, in 1918), and David ‘Bunny’ Garnett, Grant’s own lover. Woolf would have an intimate relationship with Vita Sackville-West; EM Forster wrote often about his desire for men, including in his then-unpublished novel Maurice; Keynes was bisexual, and had his own relationship with Grant, while Woolf described her relationship with Morrell as ‘romantic’.

A look from Dior Men’s S/S 2023, featuring a motif inspired by a work by Duncan Grant (below)

Such tales of queer love permeate ‘Bring No Clothes’; Porter says part of the aim of the exhibition was to uncover the ‘sexuality and physicality’ of the Bloomsbury Group. ‘They were all young adults in the 1920s, involved in this moment of change,’ says Porter. Stories of love between women felt particularly fascinating, and in many ways overlooked. ‘Queer women lived in a society that just pretended they didn’t exist,’ he says. ‘Gay men also didn’t have a way of being in society, but they were recognised in their illegality. By looking at them [through] the clothes, it allows you to actually be with them – it’s why with Virginia Woolf and Lady Ottoline Morrell, the relationship suddenly seemed more significant than people thought it was.’

As such, one of Porter’s favourite discoveries was a line of text whereby Woolf noted that after the publication of Orlando (1928) – in which the eponymous protagonist traverses both time and gender over the course of the novel – she and Sackville-West and both celebrated by piercing their ears. ‘It was so revelatory to read that,’ he said. ‘Woolf is so often painted to be this librarian, meek figure, but it becomes clear today that that was not her. She was hot. The leap across time – the stepping stone of clothes – lets you be with her enough to see that.’

‘Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and Fashion’ is sponsored by Dior and runs from 13 September 2023 – 7 January 2024 at Charleston in Lewes.

A fan by Duncan Grant, c. 1913-1916. It would inspire a motif in Jones’ S/S 2023 Dior Men’s collection (above)

Jack Moss is the Fashion Features Editor at Wallpaper*, joining the team in 2022. Having previously been the digital features editor at AnOther and digital editor at 10 and 10 Men magazines, he has also contributed to titles including i-D, Dazed, 10 Magazine, Mr Porter’s The Journal and more, while also featuring in Dazed: 32 Years Confused: The Covers, published by Rizzoli. He is particularly interested in the moments when fashion intersects with other creative disciplines – notably art and design – as well as championing a new generation of international talent and reporting from international fashion weeks. Across his career, he has interviewed the fashion industry’s leading figures, including Rick Owens, Pieter Mulier, Jonathan Anderson, Grace Wales Bonner, Christian Lacroix, Kate Moss and Manolo Blahnik.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss