The England women’s football kit was inspired by Wembley’s art deco architecture

We explore the architectural origins and innovative engineering behind the England women’s football kit, designed by Nike, as the team prepares to take on Spain in the World Cup final

Last summer, the Lionesses – England’s Sarina Wiegman-led women’s football squad – won the UEFA Euro 2022 final, beating Germany in front of a record-breaking 87,192-strong crowd at north London’s Wembley Stadium.

Echoes of that historic victory are found in the team’s football kit for another monumental opportunity this weekend, the 2023 FIFA World Cup final, which will take place at Stadium Australia in Sydney on Sunday (the match will kick off at 8pm local time and 11am BST). England will take on Spain for the title in a blockbuster match-up of two footballing nations.

The England women’s football kit, which is designed by Nike, finds its roots in ‘the heritage of Wembley’, a stadium that began its construction in the 1920s and celebrates its centenary this year. The national stadium continues to set the record for the two highest-attended women’s football matches ever, both set at England women’s team matches, and has also been the site of numerous other sporting occasions, including the 1966 World Cup final – England’s last World Cup triumph – and the 1948 Olympics.

The story behind the 2023 England women’s football kit

The England women’s football team in the home and away kits for this year’s World Cup

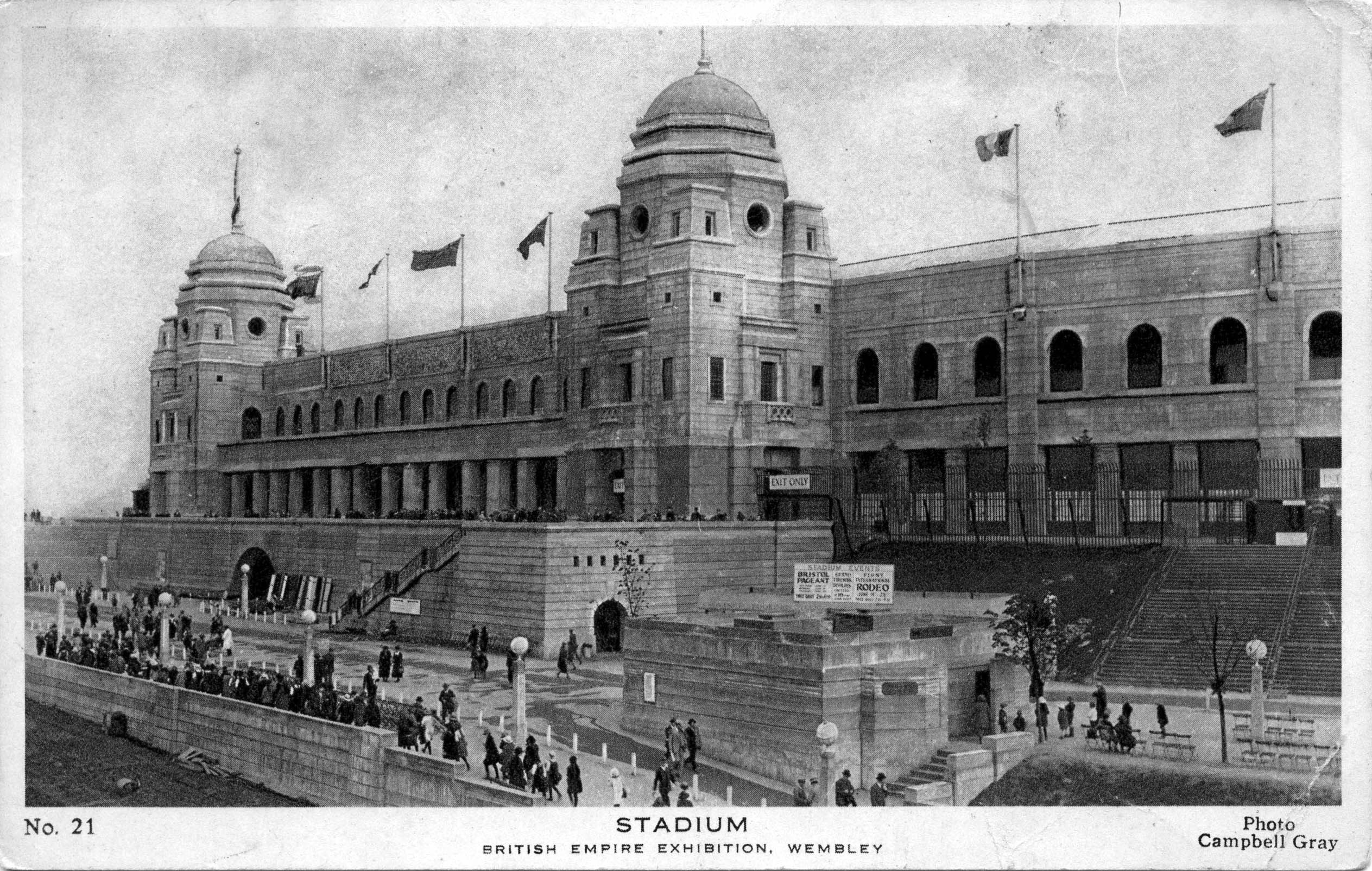

The kit itself draws on the original Wembley Stadium, which was inaugurated in 1923 and is known for its distinctive white ’twin towers’ (the site was rebuilt in the 2000s to a design by Populous and Foster + Partners, opening in 2007). At the time of its original completion, England was in the midst of the art deco movement – a gleaming, decorative style that emerged in a period of post-First World War prosperity – a mood reflected Sir Robert McAlpine’s stadium, built to house the British Empire Exhibition of 1924-25. Its first event was the FA Cup Final of April 1923; in the century that has followed, it has become perhaps the world’s most famous football stadium. ‘Wembley is the cathedral of football,’ said Pelé. ‘It is the capital of football and it is the heart of football.’

The kit’s design – white with blue shorts for home matches, a paler blue with matching shorts for away – draws inspiration from art deco‘s ‘colour, patterns and gradients’, according to Nike. The home kit references ‘the original Wembley’s white, chalky brick exterior’ in its just off-white shade, while also providing an homage to the 1984 England women’s team, which was the first women’s team assembled for the country. The home kit follows the same shades of blue and white as the original 1984 uniform.

The away kit, meanwhile, is distinct for its geometric patterned design, a direct nod to the decorative motifs of the art deco movement. The slight gradient is once again a reference to Wembley’s original chalky façade, as well as screever chalk paintings – the street paintings drawn on pavements by ‘screevers’ outside sporting events or at tourist attractions – a style which was popular at the time. It is also notable for its pale blue colour, a departure from the usual red that both the men’s and women’s England teams have traditionally worn at away games.

A postcard of the white ‘twin towers’ of Wembley Stadium, dating back to when it hosted the British Empire Exhibition of 1924-25

Though it is perhaps England goalkeeper Mary Earps’ patterned jersey, in gradient shades of red, orange and pink, which has proved the most talked-about garment of the tournament, having not yet been made available for sale by Nike. ‘I can’t really sugar-coat this in any way, so I am not going to try. It is hugely disappointing and very hurtful,’ she said at the opening of the tournament of the decision. After England’s slew of wins and progress during the World Cup, a petition to get the jersey into production has garnered over 45,000 signatures (Nike is yet to comment on its plans to produce the shirt).

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Each element of the kit is completed with typography by pioneering British graphic designer Neville Brody, who is best known for his work on The Face magazine in the 1980s and whose subsequent clients have included Apple, BBC, The Times and Channel 4 (he also created a special-edition ‘blank canvas’ cover for Wallpaper’s August 2009 edition). Here, he adapted fonts created for the men‘s team in 2014, alongside a lighter font with ‘adjusted angles’ to adapt to the women’s uniform’s scale.

The designs have proved popular, with Google searches for ‘Lionesses shirt’ and ‘England shirt’ purportedly rising by up to 4,000 per cent ahead of the final, with the most searched-for styles including forward Lauren Hemp, captain Leah Williamson, and goalkeeper Earps.

Lauren James in the team’s away kit, featuring geometric motifs inspired by the art deco movement

Nike also produced the kit for 12 other nations in this year’s women’s World Cup alongside England, including hosts Australia and New Zealand, as well as the Netherlands, Nigeria, USA and France. Each features a similar technical design and cut, part of a growing initiative from the brand to engineer sporting garments specifically for the top level of women’s sport (Nike says designs for this World Cup are backed by the brand’s ‘largest-ever investment in women’s specific innovation’).

Led by body mapping, 3D-rendering and data-driven technologies, each element is specifically designed for a woman’s body in movement, the brand noting that each seam, sleeve and sweatline was placed to ensure ’no distractions’ on the pitch. Such elements were fitted ‘pixel-by-pixel’, according to Nike, whereby ways to interchange mesh and ribbed textures were able to be done digitally, a move forward from the designs for the 2019 World Cup. These digital renderings were first tested on a female football avatar, before being tested on the pitch by players themselves.

The England team’s kit also features integrated ‘Nike Leak Protection: Period’ technology, an ultra-thin absorbent lining for more comfortable bleeding if a player is on her period during a match. Women‘s periods were also part of the shift from white to blue shorts for the home kit, after players like Beth Mead spoke out about the impracticality of white shorts for women during the Euro 2022 competition.

England’s ‘Three Lions’ emblem, here crafted from 100 per cent ‘Nike Grind’, an innovative recycled material made from manufacturing leftovers and recycled shoes

The Nike kits are also their most sustainable yet – digital testing and prototyping lowered fabric waste of physical samples, while fabric yield went up to 85 per cent compared to the 40 to 50 per cent of the 2019 World Cup. The kits themselves, meanwhile, are crafted from at least 80 per cent recycled material which is derived from recycled plastic bottles, while federation crests, signature Nike ’Swooshes’ and trims are made from 100 per cent ‘Nike Grind’, a recycled material made from manufacturing leftovers, recycled post-consumer shoes (from the brand’s ‘Reuse-a-shoe’ program) and unsellable garments.

‘The future of the game is critically important to these athletes, making sustainability of the gear they wear essential,’ says Nike. ‘England’s kit is a reflection of listening to the voice of the athlete.’

Jack Moss is the Fashion Features Editor at Wallpaper*, joining the team in 2022. Having previously been the digital features editor at AnOther and digital editor at 10 and 10 Men magazines, he has also contributed to titles including i-D, Dazed, 10 Magazine, Mr Porter’s The Journal and more, while also featuring in Dazed: 32 Years Confused: The Covers, published by Rizzoli. He is particularly interested in the moments when fashion intersects with other creative disciplines – notably art and design – as well as championing a new generation of international talent and reporting from international fashion weeks. Across his career, he has interviewed the fashion industry’s leading figures, including Rick Owens, Pieter Mulier, Jonathan Anderson, Grace Wales Bonner, Christian Lacroix, Kate Moss and Manolo Blahnik.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

‘Help me go faster’: How Nike Air is priming its athletes for Olympic success

‘Help me go faster’: How Nike Air is priming its athletes for Olympic successAhead of the Paris 2024 Olympics, Nike’s chief design officer Martin Lotti opens up to Wallpaper* about its latest high-performance sneakers, developed alongside world-leading athletes and honed using AI technology

By Ann Binlot

-

Nike celebrates womanhood with ‘Goddess Awakened’, an immersive dance performance in Paris

Nike celebrates womanhood with ‘Goddess Awakened’, an immersive dance performance in ParisNike Women united with polymathic choreographer Parris Goebel on a performance that paid homage to ’the collective power of womanhood through movement, style and self-expression’

By Jack Moss

-

Sotheby’s Louis Vuitton and Nike ‘Air Force 1’ by Virgil Abloh auction raises $25.3 million

Sotheby’s Louis Vuitton and Nike ‘Air Force 1’ by Virgil Abloh auction raises $25.3 millionTwo hundred pairs of the limited-edition trainers fetched a total of $25.3 million, with proceeds going to the The Virgil Abloh™ “Post-Modern” Scholarship Fund, the most valuable charitable sale at Sotheby’s in nearly a decade

By Laura Hawkins

-

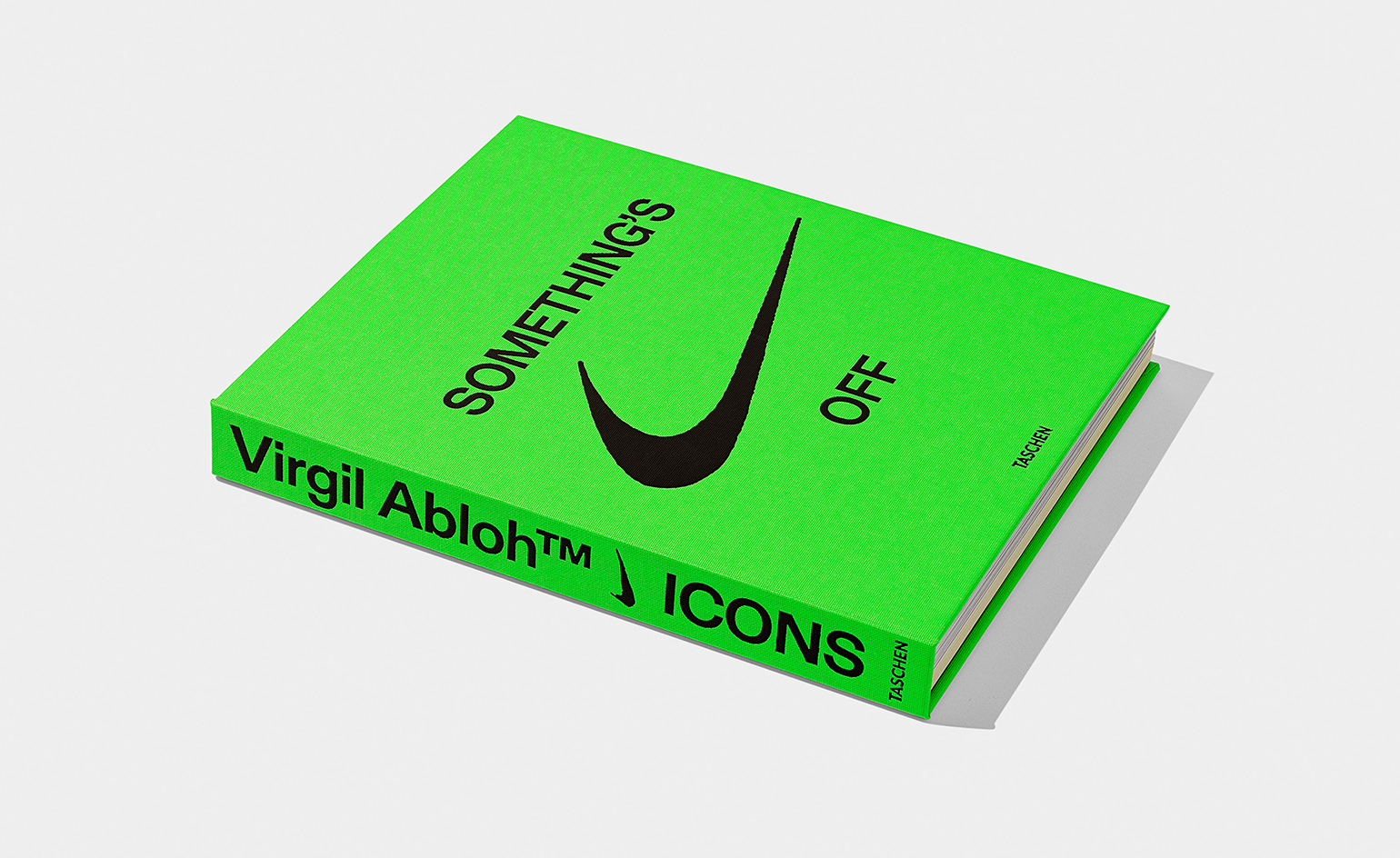

‘Icons’ by Virgil Abloh and Nike celebrates the design history of ‘The Ten’

‘Icons’ by Virgil Abloh and Nike celebrates the design history of ‘The Ten’As rumours swirl around the release of ‘The 20', Virgil Abloh and Nike release the Taschen-published tome ‘Icons', which charts the making of the creative polymath and American sportswear giant's sneaker collaboration ‘The 10'

By Laura Hawkins

-

Tread lightly: eco trainers to minimise your carbon footprint

Tread lightly: eco trainers to minimise your carbon footprintBy Nick Compton

-

Nike and Virgil Abloh unveil creative summer residency in Chicago

Nike and Virgil Abloh unveil creative summer residency in ChicagoBy Pei-Ru Keh

-

Unpacking Tom Sachs and Nike’s latest space age sneaker

Unpacking Tom Sachs and Nike’s latest space age sneakerBy Dal Chodha

-

Just for kicks: Nike and Virgil Abloh get in step

Just for kicks: Nike and Virgil Abloh get in stepBy Pei-Ru Keh