How Virgil Abloh’s legacy lives on through collaboration

A year on from his death, a slew of collaborations continue to bear Virgil Abloh’s name – a testament to the enduring legacy of the polymathic designer whose curiosity spanned disciplines

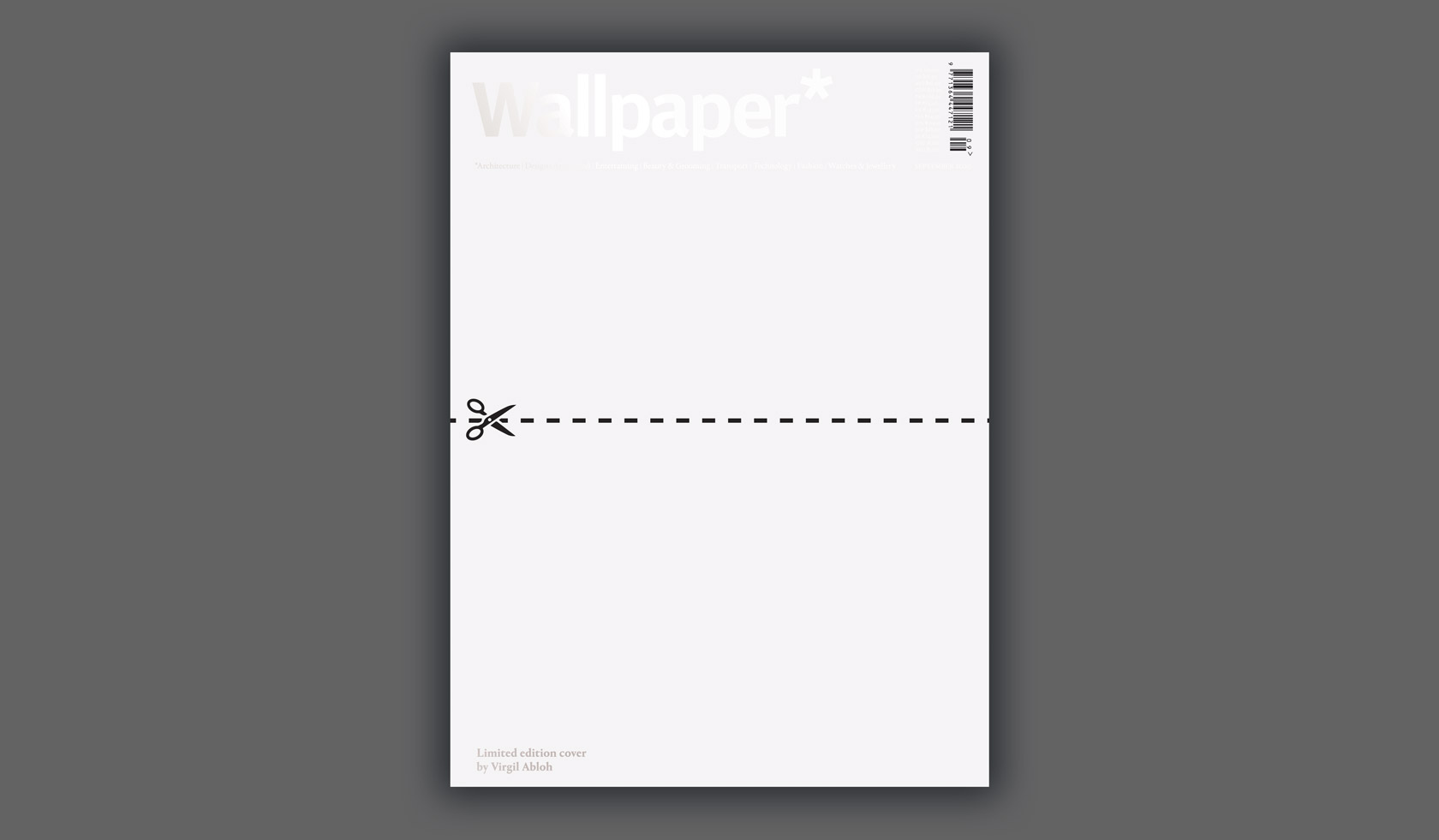

Responding to Virgil Abloh’s appointment as menswear artistic director at Louis Vuitton in 2018, British graphic design legend Peter Saville – whom Abloh called his ‘personal mentor’ – described the polymathic American designer’s work as ‘a stream of semiotic propositions, semiotic codes’. At Off-White, his 2013-founded label, and subsequently Louis Vuitton, as well as in his personal projects, Abloh was interested in signifiers, shards of text, ideas. A boot might be labelled ‘For Walking’, in the designer’s signature Helvetica font and quotation marks; collections accompanied by a pages-long glossary of Abloh-isms (‘The Vocabulary According to Virgil Abloh’); a copy of Wallpaper* designed to be sliced in half down the middle. ‘If you go to one of Virgil’s shows, it’s not really a fashion show, not in the sense that fashion ever was,’ continued Saville.

It is unsurprising, then, that of his many influences – which spanned Caravaggio and Mies Van de Rohe to Arthur Jafa and Miuccia Prada – it was the iconoclastic French artist Marcel Duchamp to which he most often returned (Abloh playfully referred to him as ‘his lawyer’). In particular, he was drawn to Duchamp’s conception of the readymade, how through the artist’s intervention, a toilet bowl could be transformed into an object worthy of display on a gallery plinth. Of that 1917 work – a porcelain urinal, titled Fountain and signed with the pseudonym ‘R. Mutt’ – Duchamp spoke of how a quotidian object could be instilled with ‘the dignity of a work of art by the mere choice of an artist’. ‘Whether Mr Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance,’ he wrote in 1917. ‘He chose it. He took an ordinary article of life, and placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object.’

Virgil Abloh: ‘Life is collaboration’

Virgil Abloh in 2019, with ‘Color Gradient Chair’ (2018). Photographed for Wallpaper*

Such a description proves equally applicable to Abloh’s approach, which took recognisable objects and transformed them by adding a slogan or aphorism, or shifting their design in barely perceptible ways (in a presentation titled ‘Personal Design Language’ he referred to the 3 per cent approach, the idea that an object needs to be altered by just 3 per cent in order to become something new). For the earlier part of his career, the focus lay largely on streetwear, attempting to shift its connotations in the 2010s, when it was largely derided by those at the echelons of fashion. ‘Streetwear in my mind is linked to Duchamp,’ he told The New Yorker in 2019. ‘It’s this idea of the readymade. I’m talking Lower East Side, New York. It’s like hip-hop. It’s sampling. I take James Brown, I chop it up, I make a new song. I’m taking Ikea and I’m presenting it in my own way. It’s streetwear 10.0 – the logic that you can reference an object or reference a brand or reference something. It’s Warhol – Marilyn Monroe or Campbell’s soup cans.’

This approach was particularly evident in his vast catalogue of collaborations at Off-White, Louis Vuitton, and under his own name, which encompassed several of the world’s most recognised brands – among them Ikea, Mercedes-Benz, Nike, Levi’s, Evian, Vitra, Jimmy Choo, Moncler, Byredo and Moët & Chandon (collaborations with brands were accompanied by others with artists, musician and filmmakers). These collaborative gestures provided much of the energy behind his work, up until the very end. Just days after the designer’s death – he died on 28 November 2021, after a two-year battle with a rare cancer called cardiac angiosarcoma (see our Virgil Abloh obituary) – Mercedes-Benz presented a Mercedes-Maybach electric show car during Art Basel Miami Beach designed in collaboration with the designer (it went ahead with the family’s wishes). ‘A humble contribution to Virgil’s vast legacy… It exemplifies the possibilities of future design and is the result of an ongoing cooperation with the polymath artist,’ the car company said at the time.

In the year since his death, Abloh’s legacy has lived on through such collaborations, several of which were worked on by the designer and then released posthumously, including those with Church’s, Alessi, Cassina and Victorinox. True to Abloh’s vision, it is fitting that these encompass brands that represent the pinnacles of their various practices, oftentimes chosen for their synonymy with a singular product (such is the case with Victorinox, which is forever linked with the Swiss Army Knife, or Church’s, with shoes). These interventions reflected Abloh’s work as menswear artistic director of Louis Vuitton – itself synonymous with the very pinnacle of luxury fashion – where he riffed on the house’s archetypal codes through his distinct lens. The implications of his appointment at Louis Vuitton have been well documented, marking the first Black artistic director in its history. ‘To show a younger generation that there is no one way anyone in this kind of position has to look is a fantastically modern spirit in which to start,’ he said on the day of the announcement.

The backdrop for Louis Vuitton’s S/S 2022 menswear show in Miami, which paid tribute to the late designer

Later, in 2020, he was more explicit about the uniqueness of his position in a document titled ‘Manifesto’ which was distributed with his S/S 2021 menswear show. ‘Every season, my team updates “The vocabulary according to Virgil Abloh: A liberal definition of terms and explanation of ideas”. Under I for irony: “The presence of Virgil Abloh at Louis Vuitton.” For all intents and nuances, I have often spelt out the interceptive reality of myself as a Black man in a French luxury house,’ he wrote. ‘This is my invitation to move forward together with awareness, hope and determination. You are witnessing unapologetic Black imagination on display.’

---

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Abloh’s various collaborations often began with what he called a ‘tourists versus purists’ ideology, the ‘organising principle’ of his entire output. ‘It’s my main device to understand the sections of culture that move culture forward,’ he said in 2019. ‘You have a purist, that’s like, “I know the whole art history of everything, you can’t do this, this was done 20-times before you thought of it”. Like, this is the pure institution. Then there’s the tourist, who’s bright-eyed, curiosity-driven, that has a lust for learning, and they support whatever.’ (Abloh saw himself as both.)

‘We met a decade ago at a dinner in Milan,’ says fashion critic Anders Christian Madsen, a longtime collaborator with Abloh, who earlier this month released his Assouline-published book Louis Vuitton: Virgil Abloh, which documents the designer’s time at the house. ‘He came in, sat down next to me, we started talking, and we never stopped. Virgil always talked about fashion purists versus tourists: the establishment versus those who aspire towards it. During our friendship and all the work we did together, those roles melted together for both of us. Our friendship and collaboration were founded in a curiosity for the things that set us apart – quite a rarity in this day and age.’

Madsen believes this ‘tourists versus purists’ dichotomy was at the heart of Abloh’s approach to collaboration: ‘When you take one domain of knowledge and introduce it to another – whether they’re founded in completely different practices or cultures, or similar worlds – a sort of immaculate conception takes place. You enlighten different groups of people about things they never knew about or never felt they had access to. You create democracy and inclusivity, a transition that doesn’t just add to your business value but to your human value, too.’

Cassina ‘Modular Imagination by Virgil Abloh’

Indeed, several of those who collaborated with the designer have expressed this feeling of ideological exchange. In the foreword to his book Virgil Abloh: Figures of Speech – an accompaniment to the exhibition of the same name which began at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago in 2019 and has since toured various cities – curator Michael Darling calls it a ‘loop of interdependence’. ‘Collaboration is integral to Abloh’s approach: not only does he draw from a dizzying array of sources, but also works with and facilitates connections among graphic designers, musicians, fashion designers, and visual artists. This broad engagement with the cultural landscape is both generous and generative.’

Spanish architect and designer Patricia Urquiola, who collaborated with Abloh in various capacities, including overseeing his collaboration with Cassina (Urquiola is art director of the Italian furniture brand) notes that ‘between art and music and fashion, so many lenses were part of his approach’. Titled ‘Modular Imagination’ and released posthumously, the collaboration comprises various modular blocks which can be built into a chair, a table, or more unconventional shapes (Cassina says it will enter their permanent catalogue as a mark of respect to the designer).

‘I think we are going to see a lot more of these types of situations where people are collaborating with people with another point of view,’ she says, noting that Abloh reflected her own desire to cross disciplines in her working practice. ‘I think in our line of work we should be doing more capsules, to give new voices to companies. They aren’t always going to be perfect, but they are a test.’

CEO of Victorinox, Carl Elsener Jr, who earlier this month released a limited-edition Swiss Army Knife made in collaboration with Abloh and Off-White, speaks of the designer’s ability to reflect a brand’s heritage in a new light (the collaboration was part of a wider Off-White project, titled ‘Equipment c/o Post Archive Faction c/o Victorinox c/o Helinox’, which collates 12 items ‘that explore the meaning and survival of humanity in our contemporary landscape’). ‘He was thinking: what are the tools humans have used to survive?’ says Elsener, noting that it led Abloh towards the Swiss Army Knife, a multi-use object which echoed the functions of stone-age flint. ‘He was looking at something existing and bringing new elements to it – while making this connection to the very beginning of time.

‘[The collaboration] taught us we could be more open. He really had this openness, this creativity, but then the details and the function are still really important… I think the collaboration made us more daring.’

In a previous interview with Wallpaper*, Alberto Alessi, president of Alessi – which released its own posthumous collaboration with Abloh featuring a metal knife, fork and spoon with a carabiner – concurred. ‘I found that Virgil had a completely different way to look at things and objects,’ says Alessi. ‘I remember that the first reference he showed me was a wrench – very far from the elegance of what we habitually think of as good design. It was almost brutalist. I found this very interesting, as for us it was a new approach. Alas, we had very little time to make our collaboration with Virgil, but I am so glad we did.’

Elsener says he is ‘proud’ of his collaboration with Abloh. ‘The only sad thing is that Virgil isn’t here too.’

---

In September 2020, Abloh created a limited-edition cover of Wallpaper* – matt white, the only decorative flourish is a dotted line and scissor symbol, the suggestion being that it should be sliced straight down the middle by the reader. ‘Cutting the physical object makes the magazine come alive and reinforces the concept that the magazine's media may be physical, but it also occupies a space figuratively and literally,’ he said at the time. He called the act democratic. He personally sliced and signed 184 copies; these special editions were playfully titled ‘2 for the Price of 1’, with proceeds going to the Virgil Abloh “Post Modern” Scholarship Fund, which fosters inclusion within the fashion industry by providing scholarships to ’students of academic promise of Black, African-American, or African descent’.

‘It’s important that the door is left open for kids just like me,’ he said to Wallpaper* at the time. ‘The future of fashion, the future of design, the future of management and all these careers is an urgent matter. It is vital that figures like me embed within their work a component to fortify that effort.’

‘He made high fashion feel like a domain in which everyone can participate,’ says Madsen. ‘He and his work transcended the boxes in which we place people and fashion, and for that reason, an infinitely broad spectrum of people could relate.’ Collaboration, he continues, was essential to this way of working. ‘He was a second-generation American-Ghanaian man, who grew up in the hip-hop community, studied architecture and became an establishment fashion designer. His background was literally about clashing cultures, so that impulse was instinctive in everything he did. But it wasn’t just practical. He saw unity in transcendence.’

Abloh’s final collection for Off-White – A/W 2022 – was displayed in March 2022 at Paris Fashion Week, featuring a 28-piece haute couture collection produced and fitted prior to his death the previous November. A pair of white flags hung over the runway, printed with perhaps his most famous aphorism, ‘Question Everything’. Off-White call the phrase ‘Virgil Abloh’s guiding philosophy’; at the 2019 Figures of Speech exhibition, the same message was printed on a black flag.

In many ways, his collaborations were questions in themselves. What might an object look like when placed in a new context? How do we perceive something when its design is changed, even by just 3 per cent? How can the familiar be made unfamiliar? Definite answers weren’t important. Curiosity was everything.

Now led by image and art director Ibrahim Kamara, this impulse continues at Off-White; the recent S/S 2023 show featured collaborations with musical duo Tshegue and movement director Nicolas Huchard. ‘There is a regenerative spirit as we approach the cusp of something new. In the unknown, there is the freedom to imagine. Possibilities are boundless,’ read the collection notes.

‘Where I think art can be sort of misguided is that it propagates this idea of itself as a solo love affair – one person, one idea, no one else involved,’ Abloh said in 2018. ‘Life is collaboration.’

A post shared by Off-White™ (@off____white)

A photo posted by on

Jack Moss is the Fashion Features Editor at Wallpaper*, joining the team in 2022. Having previously been the digital features editor at AnOther and digital editor at 10 and 10 Men magazines, he has also contributed to titles including i-D, Dazed, 10 Magazine, Mr Porter’s The Journal and more, while also featuring in Dazed: 32 Years Confused: The Covers, published by Rizzoli. He is particularly interested in the moments when fashion intersects with other creative disciplines – notably art and design – as well as championing a new generation of international talent and reporting from international fashion weeks. Across his career, he has interviewed the fashion industry’s leading figures, including Rick Owens, Pieter Mulier, Jonathan Anderson, Grace Wales Bonner, Christian Lacroix, Kate Moss and Manolo Blahnik.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

Louis Vuitton drafts contemporary artists to use the house’s silk ‘carré’ scarf as a colourful canvas

Louis Vuitton drafts contemporary artists to use the house’s silk ‘carré’ scarf as a colourful canvasIn a tradition which dates back to the 1980s, Louis Vuitton has asked five artists to reimagine its silk carré scarf using floral motifs

By Jack Moss

-

For A/W 2024, the working uniform gets a futuristic spin

For A/W 2024, the working uniform gets a futuristic spinSculpted silhouettes, unexpected textures and plays on classic outerwear meet in the A/W 2024 collections, providing a twisted new take on city dressing

By Jack Moss

-

The breathtaking runway sets of S/S 2025, from beanbag animals to a twisted living room

The breathtaking runway sets of S/S 2025, from beanbag animals to a twisted living roomWallpaper* picks the best runway sets and show spaces of fashion month, which featured Bottega Veneta’s beanbag menagerie, opulence at Saint Laurent, and artist collaborations at Acne Studios and Burberry

By Jack Moss

-

The A/W 2024 menswear collections were defined by a ‘new flamboyance’

The A/W 2024 menswear collections were defined by a ‘new flamboyance’Sleek and streamlined ensembles imbued with a sense of performance take centre stage in ‘Quiet on Set’, a portfolio of the A/W 2024 menswear collections photographed by Matthieu Delbreuve

By Jack Moss

-

Colourful luggage to brighten up your summer

Colourful luggage to brighten up your summerEschew grey, navy and black for vibrantly hued luggage that will stand out on the airport belt and add colour to summertime escapes

By Jack Moss

-

Women’s Fashion Week S/S 2025: what to expect

Women’s Fashion Week S/S 2025: what to expectNext week sees the arrival of Women’s Fashion Week S/S 2025, with stops in New York, London, Milan and Paris. Here, our comprehensive guide to the month, from Alaïa’s arrival in New York to Alessandro Michele’s Valentino debut

By Jack Moss

-

‘Things are not what they seem’: Unpacking the S/S 2025 menswear shows

‘Things are not what they seem’: Unpacking the S/S 2025 menswear showsWallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss explores the trends and takeaways from this season’s menswear shows, from an embrace of ‘irrational clothing’ to couture-level craft and eclectic new takes on tailoring

By Jack Moss

-

Paris Fashion Week Men’s S/S 2025: Loewe to Dries Van Noten

Paris Fashion Week Men’s S/S 2025: Loewe to Dries Van NotenWallpaper* picks the best moments of Paris Fashion Week Men’s S/S 2025, from ‘hypnotic precision’ at Loewe to Dries Van Noten’s final show, as well as the latest outings from Pharrell Williams, Kim Jones and Grace Wales Bonner

By Jack Moss