Photographing Alexander McQueen: Ann Ray discusses her creative partnership with the designer

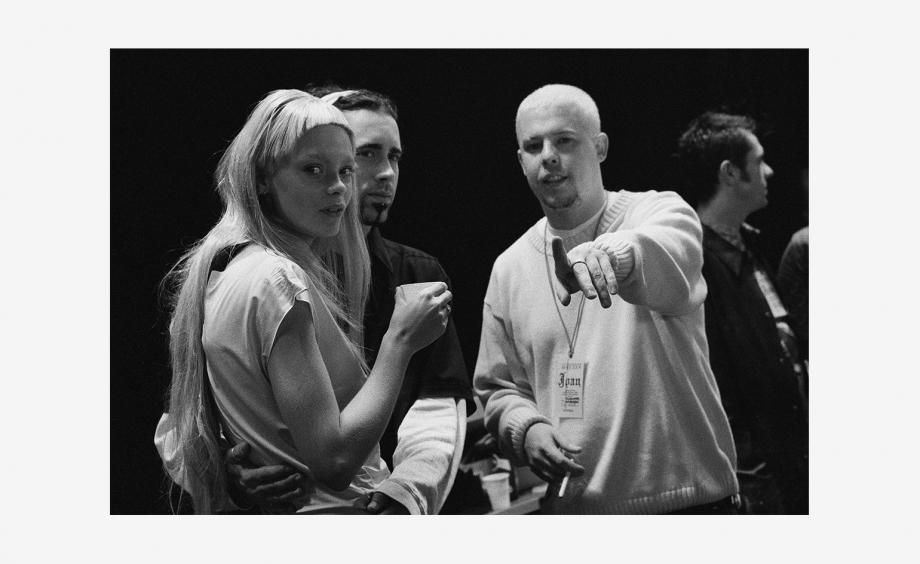

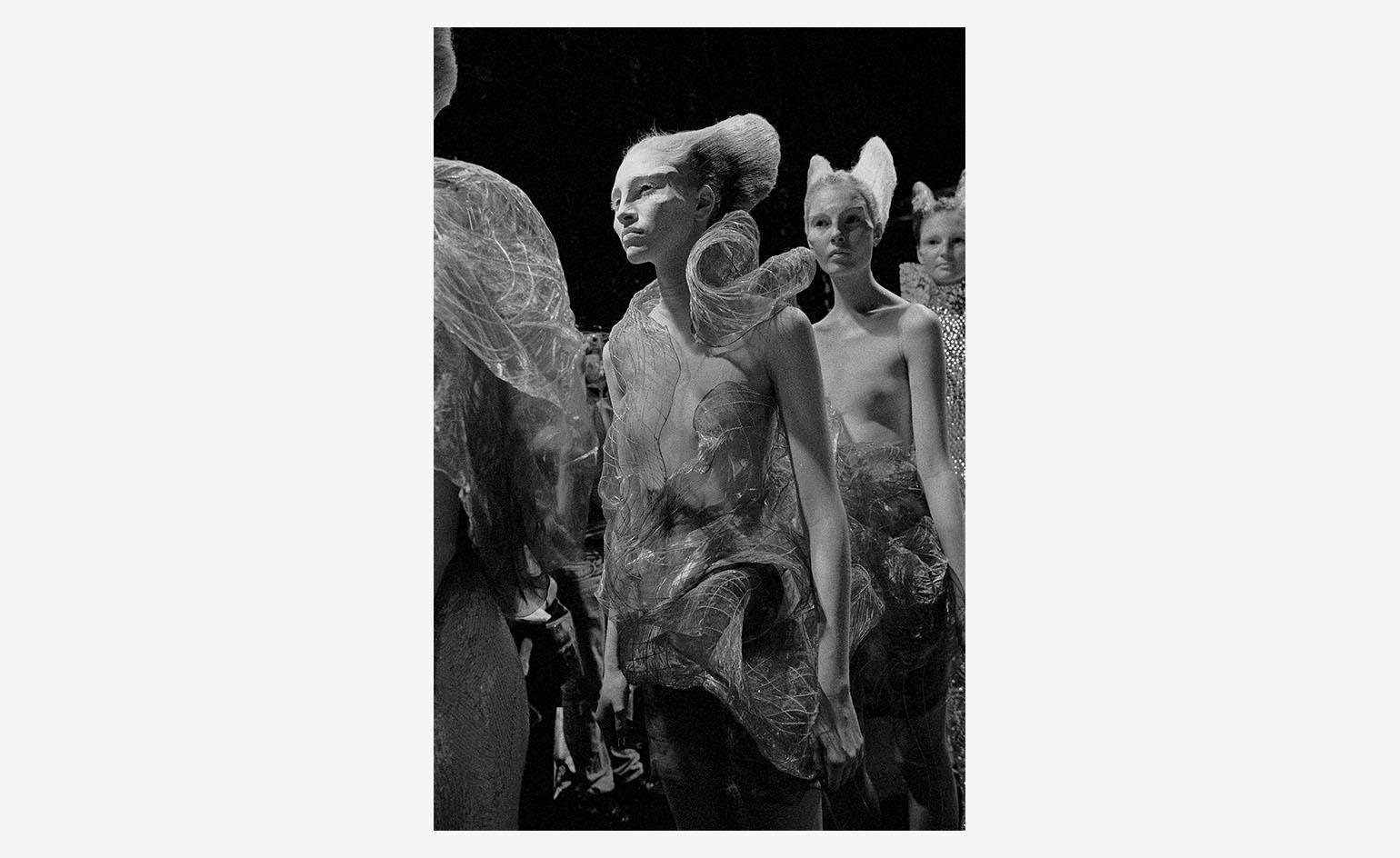

‘We met in our mid-twenties in late 1996 in Paris at Givenchy,’ says Ann Ray of her first encounter with the late Alexander McQueen, who that year was made chief designer of the couture maison. The French photographer formed a long-lasting relationship with the renowned London-born designer, and during the course of their creative tenure, captured over 35,000 analogue photographs of him at work; be it a 1998 candid backstage portrait of McQueen alongside model Jaime King, or a line up of spectral sea monster-like models waiting to take to the catwalk at his eponymous ‘Plato’s Atlantis’ 2009 show.

Next month, ‘The Unfinished Lee McQueen,’ an exhibition of Ray’s images of the designer’s career goes on display at Rencontres d’Arles photography festival in France. ‘What mattered when curating this exhibition was to be true, to Lee and to myself; to draw a honest portrait of the man I knew, through his life and work’ Ray explains. ‘The exhibition is filled with portraits; of Lee, of his close collaborators, and the women [models] he had chosen to work with.’

As she prepares for the opening of this expansive show, Wallpaper* caught up with Ray to delve further into an intimate creative relationship that lasted until 2010, the year of McQueen’s passing.

Wallpaper*: What was your first impression of McQueen?

Ann Ray: It was one that remained over the years: a lovely man, big-hearted, sensitive and loyal, incredibly talented, reserved and intimidating. Trust would not be given easily, but if it was, it would last for a very long time, or forever.

W* The course of your creative relationship ran for 13 years and you took over 35,000 analogue photographs. McQueen must have become such an important part of your life?

AR: People like Lee McQueen are rare and precious. They have a massive impact on whoever has the privilege to get close to them. If I have one talent, it’s to recognise talent when I see it. I enjoy ‘serving’ these artists with my art. Nowadays McQueen has become a legend and everybody calls him a ‘genius’, but in the late Nineties it was very different. Lots of editors were writing bad things about him, year after year.

The 13 years I spent photographing Lee were an act of devotion; personally and artistically. I have always been aware of the privilege it embodied. Lee was probably aware of that too. It was about trust, and art, obviously. I like to remember the simplicity, of the beginnings: ‘give me photos, I’ll give you clothes’, he said. As simple as a friends’ trade. When money is not involved, you find a way. I still do trades with close people, it’s a joy, forged in mutual respect. I love that. ‘Give me what you do best, and I’ll do the same for you’. Perfection.

W*: Your photographs capture incredibly candid moments of McQueen at work, and the ethereal beauty of his catwalk designs. How would you describe your creative chemistry?

AR: I felt extremely connected to Lee. I had the feeling I was understanding everything he was expressing in his art, and tried hard to translate what I was seeing in the most faithful way. He appeared to me as an artist, or a poet from day one. Fashion was just the medium.

Recently a close friend said to me : ‘these women [in McQueen’s shows] have never been as beautiful as in your images.’ I found this interesting and although I appreciated the compliment, beyond it I believe it’s true. These women are beautiful in a very special way, and I think this is the outcome of the creative chemistry. All the people working closely with Lee were part of this. We all went together in ‘terra incognita’ around him, we were part of the adventure in his universe. We all gave our best, and beyond. The result was a sum of joy, fear, links, connections, exchanges, unspoken secrets, in a way, leading to a climax as seen by an audience for 15 minutes.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

W*: What was it like being around McQueen?

AR: His bright side was immense, and it was contagious to anybody working with him… It’s a shame there is such a dichotomy nowadays between the man a few people knew, and the dark legend. But that’s how it is, I guess the truth is that you have to embrace the fact that a close friend is very distinct from the myth.

It happens to Lee as it happens all the time for so-called ‘genius’ or famous people. I heard that it was dark and sinister to be around Lee, that is so wrong. It was bright and joyful and fiercely crazy and exciting, however it was of course tough and difficult and heavy too – but because of myself never because of Lee.

W*: Why did you choose to shoot your photographs in analogue?

AR: For it’s timeless beauty. For the difficulty, and the challenges it involves. You have to use your imagination, and your faith, to do analogue photography in a hectic, dark, difficult context. You have to put one intention in one image. You have to stop breathing.

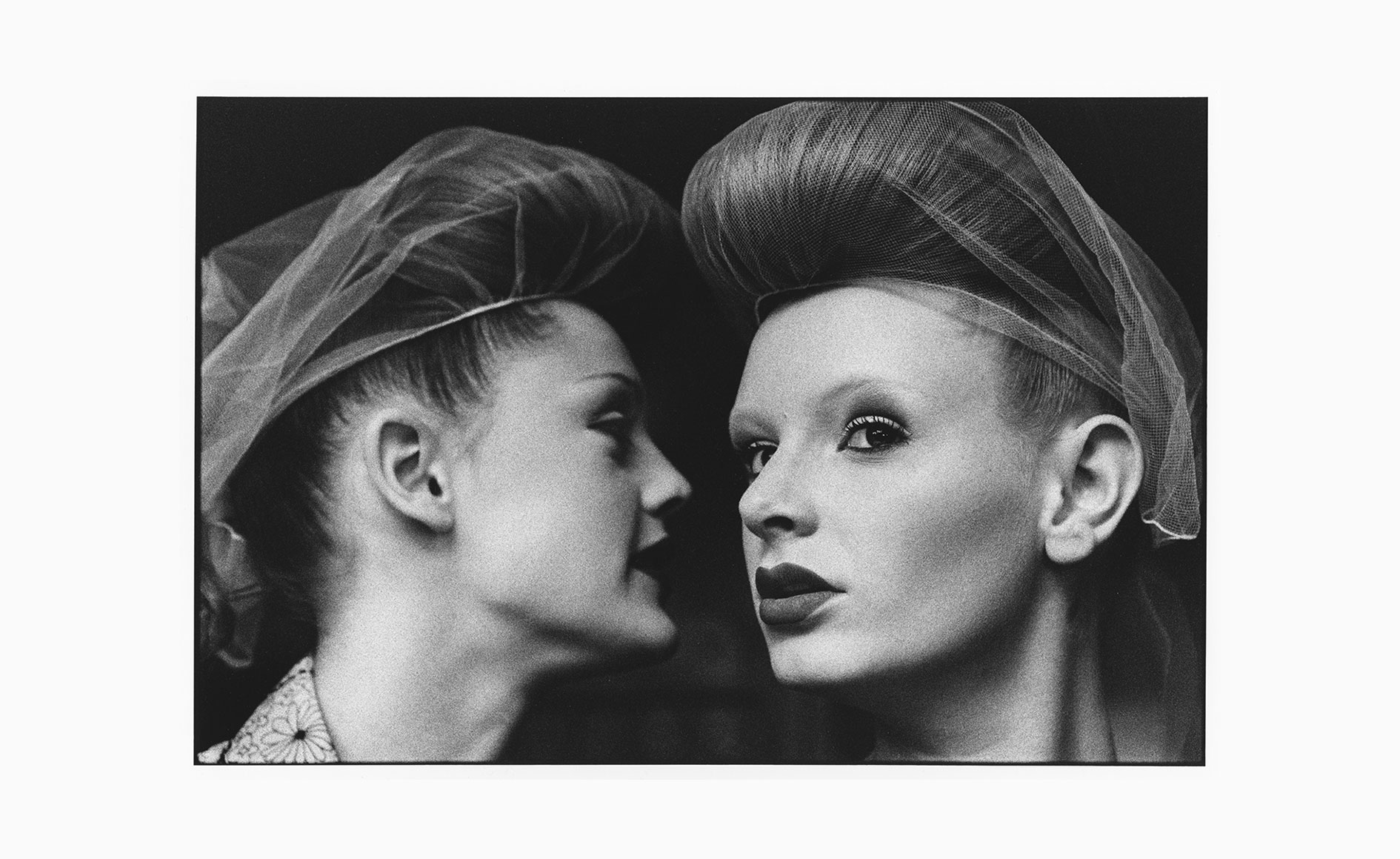

‘Be Nice’ Paris, 1998 (Jaime King) by Ann Ray. Image courtesy of the artist

W* How many portraits did you take of McQueen?

AR: I did countless portraits, I realised it recently, strangely enough, when working on the exhibition. Hundreds, I guess, I haven’t counted. It was such a natural process that I didn’t imagine I had so many of him. Some face to face, real photographic portrait sessions, especially from 1997 to early 2001, when I was living in London; and so many at work, behind the scenes, or in the studio.

Lee never realised how beautiful he was. We all have insecurities about our appearance. It’s probably one of the reasons why his appearance changed so much in 13 years. It’s also like wearing a mask. A mask is a good thing because it gives you a break from truth. It’s a protection.

To paraphrase Richard Avedon, when you’re really connected to the person you photograph, a portrait is a mix between what they want to show, what you know they are hiding, what part you decide to reveal, with full respect and their silent consent. It’s alchemy.

W* Did you experience any new revelations about your images in your organisation of the exhibition?

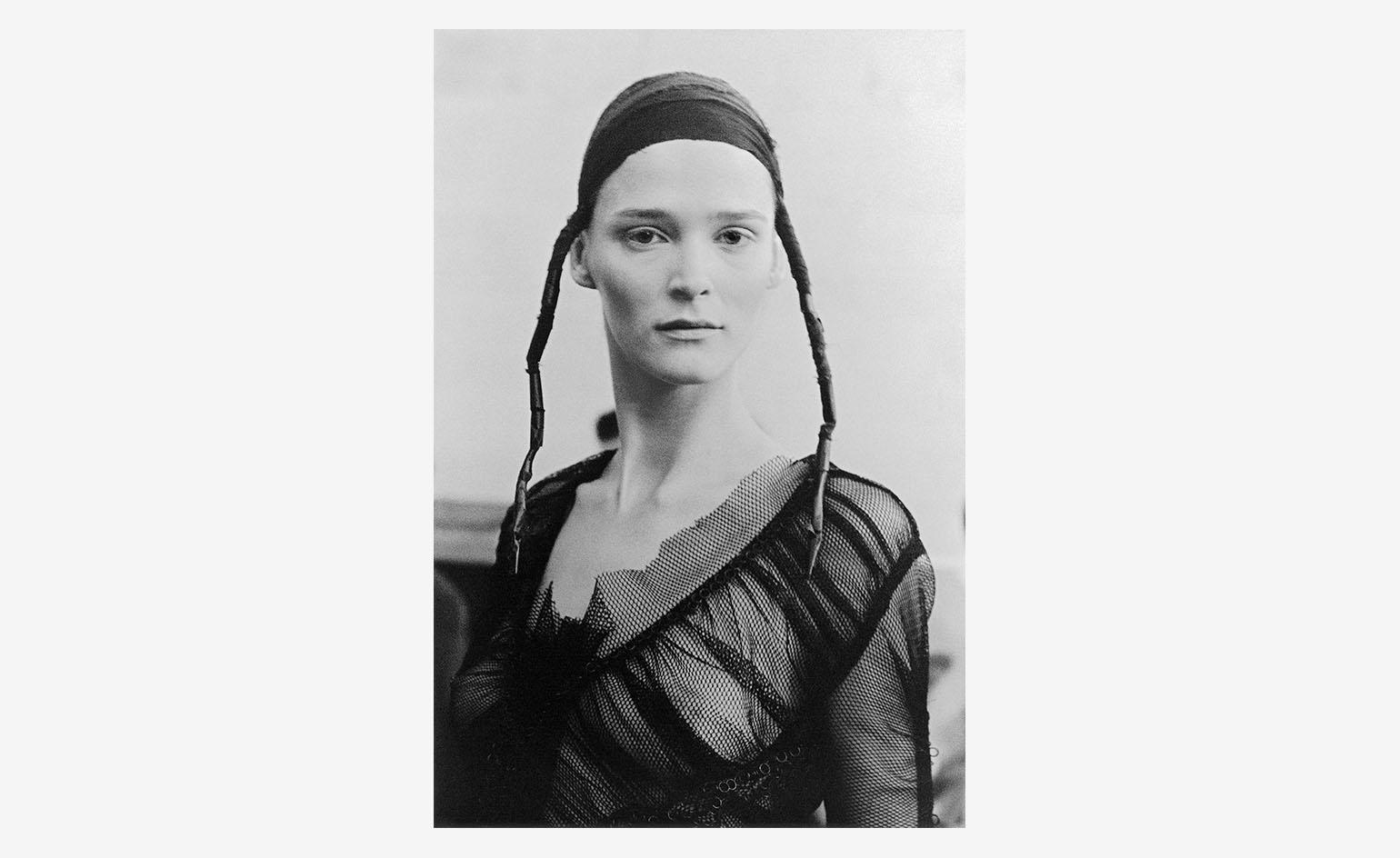

AR: I received a great help from my curator – Sam Stourdzé, director of the Rencontres d’Arles – and from my producer Myriam Blundell Phillips. Both were struck by two things: first, how Lee changed his appearance, and second, how numerous the portraits of women were I took over the years. With, or without clothes. Like ‘character studies’, since these women were indeed characters. It occurred to me that Lee would chose the women for his shows as a movie director would chose his actresses; he would even explain the intention and the body language. There were no dialogues or words, of course – these were useless. Lee had so much to say without words.

W*: It’s eight years since McQueen died. As time has passed, have you come to view the images with a different perspective?

AR: Photography and movies have always been very important in my life. I built my first lab with my brother – an amateur but super-skilled photographer, with a fabulous eye – when I was nine. My first portraits were photographing my little sister, endlessly, whereas my brother was doing the same: photographing me. We would run by the ocean to photograph it very often, especially if there was a storm. Then I used my father’s 8mm camera – bought in Japan by my Dad – for years.

The first editing I did with a movie, was physical: I was cutting and pasting, mechanically. How you use Photoshop nowadays, I did it with my hands. It was very simple to understand, even for a little girl – you don’t want it, you cut it. You just keep the best... I had to get older to fully understand and embrace the magic, power and mystery of images… I know the answers, all is almost clear now.

Photography apparently deals with death, but my photographs don’t deal with death, at all, just the opposite. They deal with life, and the celebration of life. On a very blurry time scale.

‘Deep Dive I’, Paris, 2009 (Atlantis, Yulia Lobova), by Ann Ray. Image courtesy of the artist

‘The Naked Truth, Paris, 2002’ (Supercalifragilistic, Carmen Kaas) by Ann Ray. Image courtesy of the artist

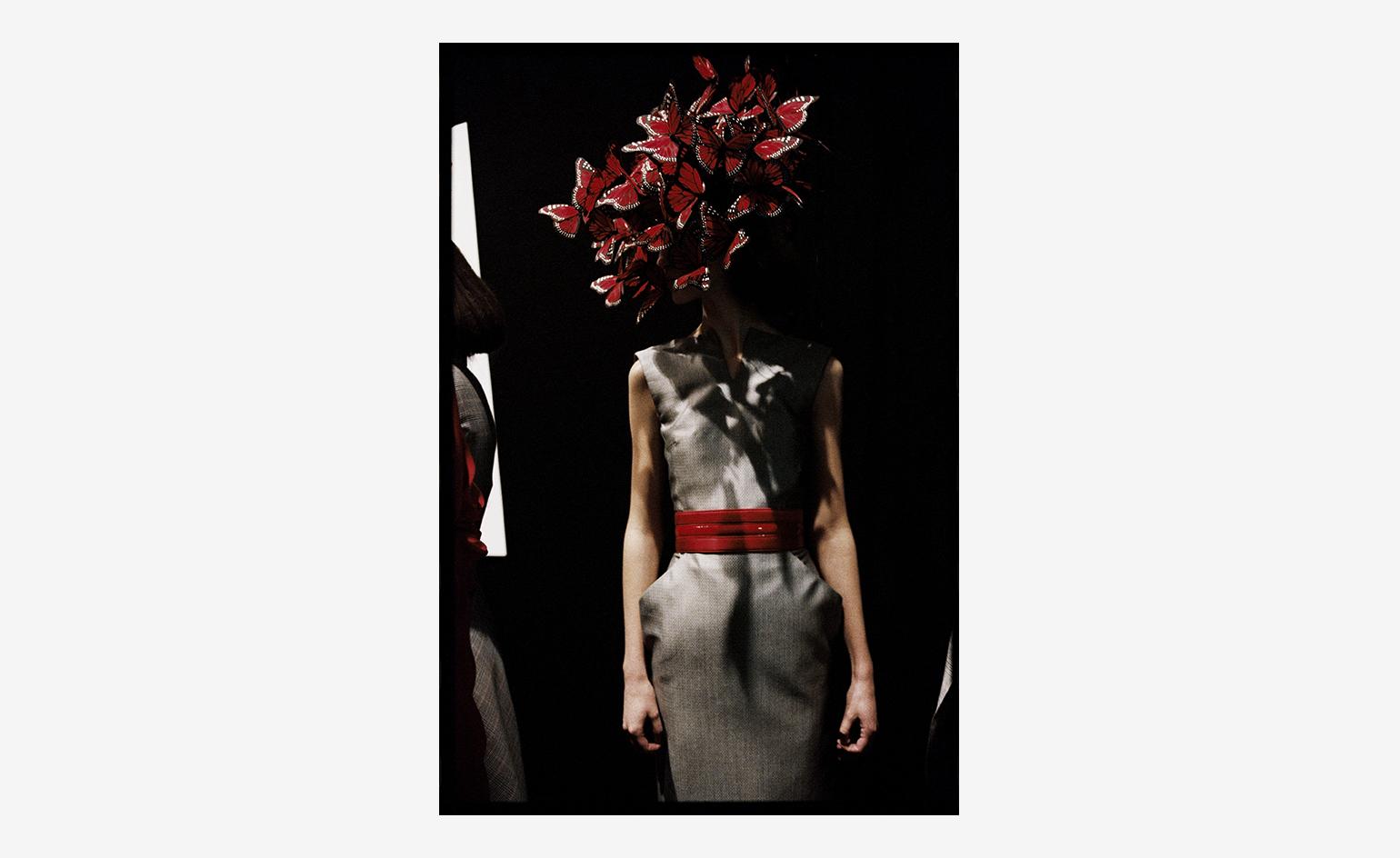

‘Flying Head’, 2007 (Philip Treacy), by Ann Ray. Image courtesy of the artist

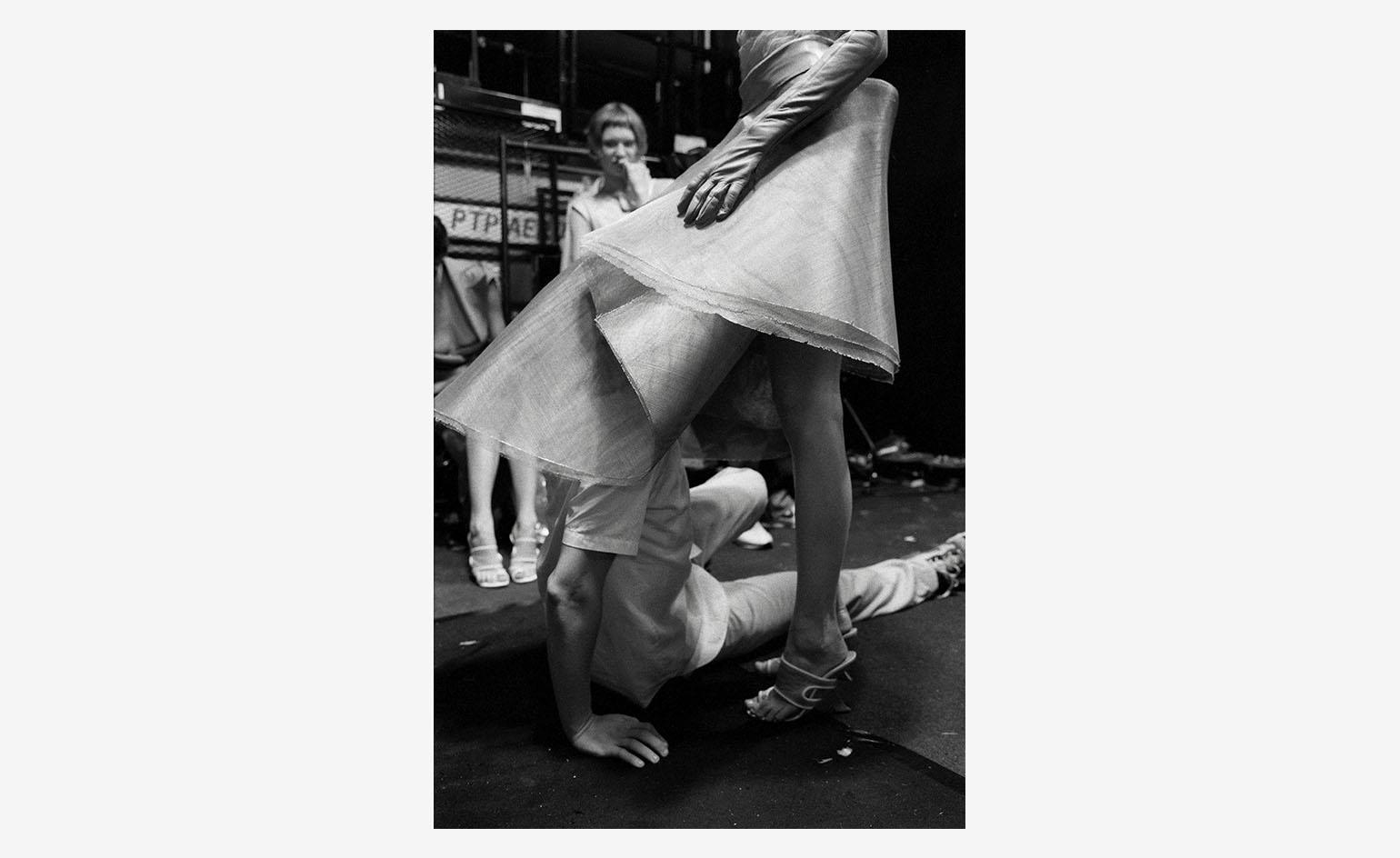

‘Mechanics’, Londres, 1998 (VOSS) by Ann Ray. Image courtesy of the artist

‘Adieu II’, Paris, 2010 (Untitled, Tanya Dziahileva) by Ann Ray. Image courtesy of the artist

INFORMATION

‘The Unfinished Lee McQueen,’ is on view from 2 July to 23 September. For more information visit the Rencontres d'Arles website; Ann Ray website

ADDRESS

Rencontres d’Arles - Atelier des Forges, Parc des Ateliers

-

Seven things not to miss on your sunny escape to Palm Springs

Seven things not to miss on your sunny escape to Palm SpringsIt’s a prime time for Angelenos, and others, to head out to Palm Springs; here’s where to have fun on your getaway

By Carole Dixon

-

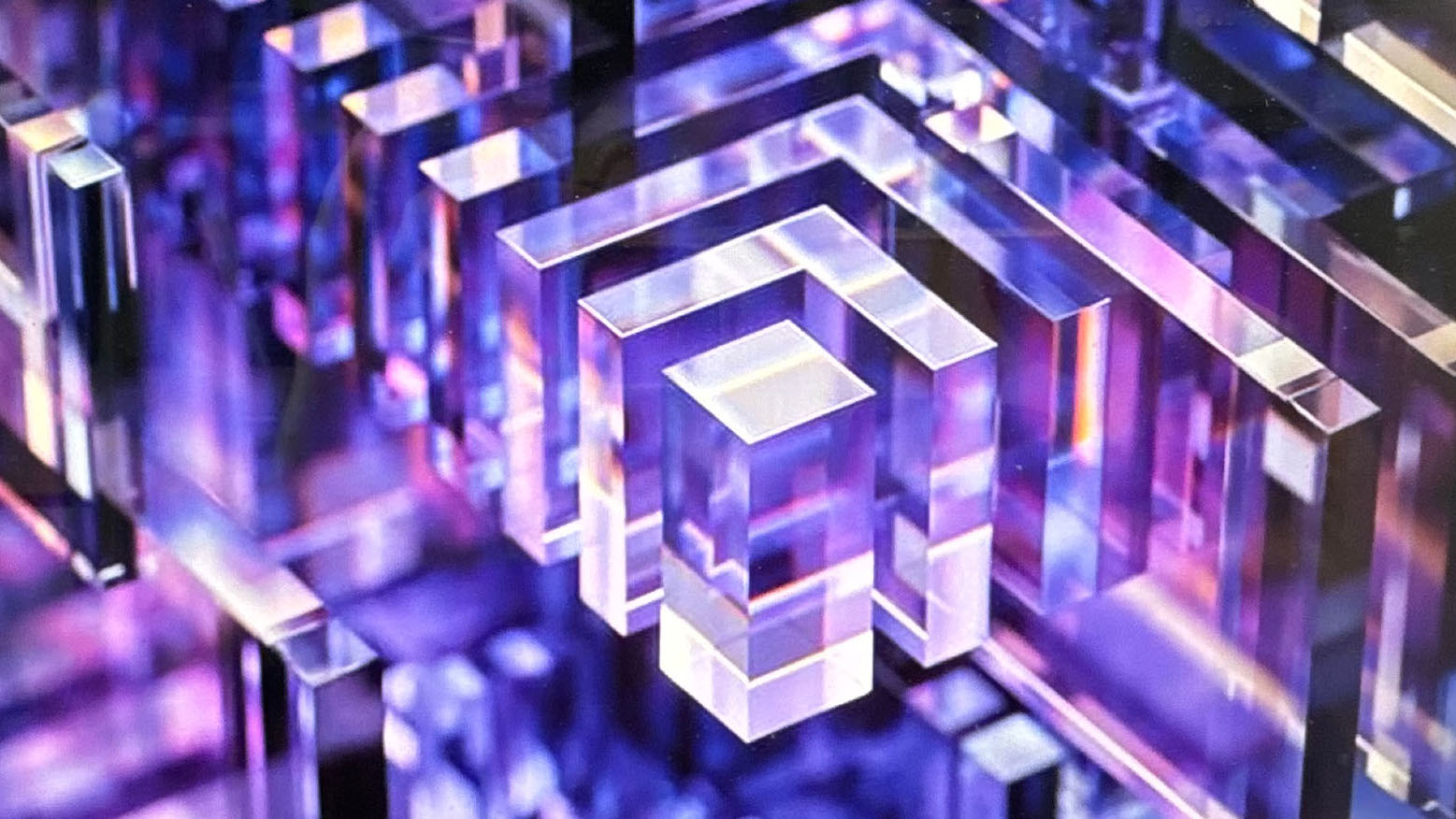

Microsoft vs Google: where is the battle for the ultimate AI assistant taking us?

Microsoft vs Google: where is the battle for the ultimate AI assistant taking us?Tech editor Jonathan Bell reflects on Microsoft’s Copilot, Google’s Gemini, plus the state of the art in SEO, wayward algorithms, video generation and the never-ending quest for the definition of ‘good content’

By Jonathan Bell

-

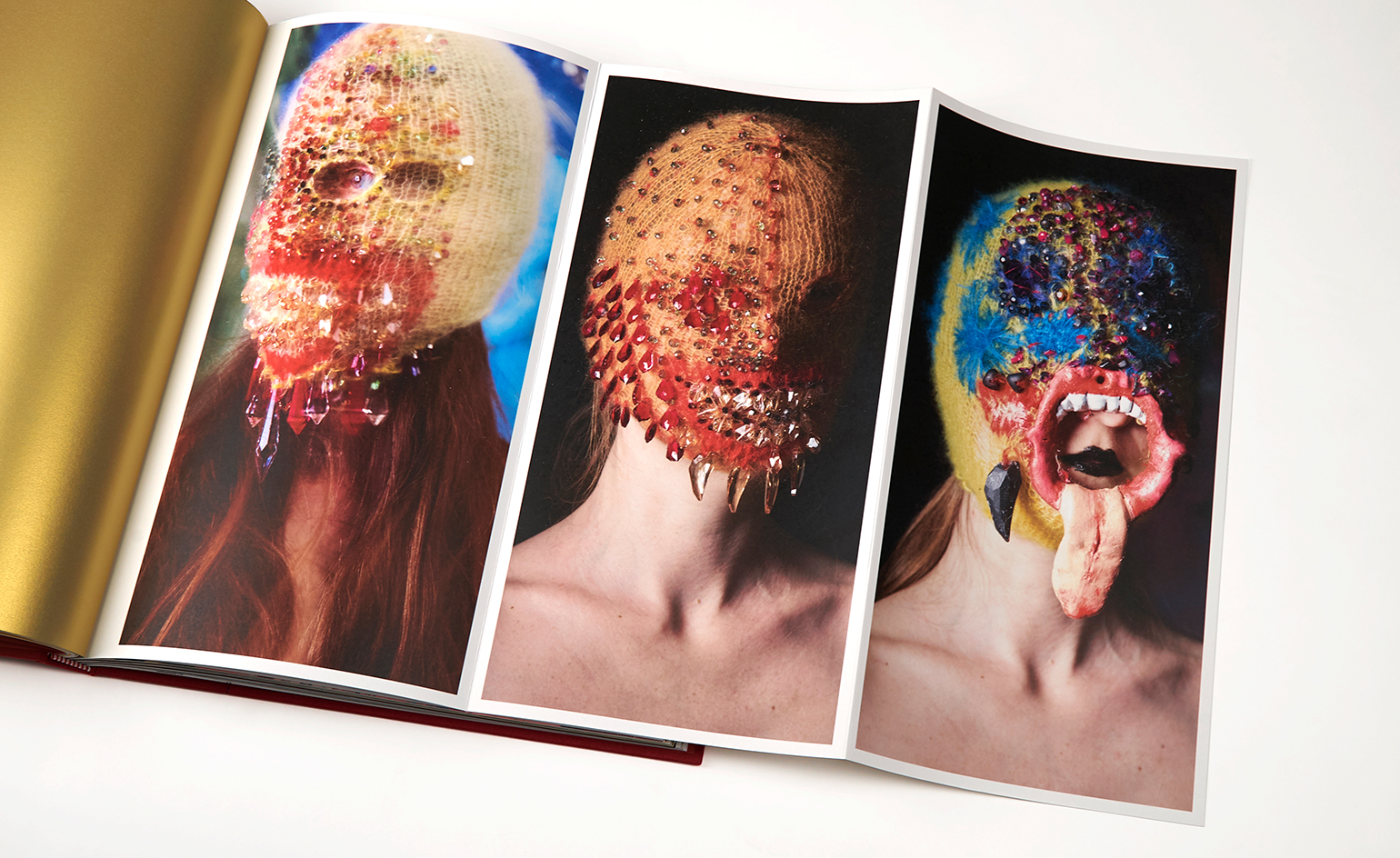

‘Independence, community, legacy’: inside a new book documenting the history of cult British streetwear label Aries

‘Independence, community, legacy’: inside a new book documenting the history of cult British streetwear label AriesRizzoli’s ‘Aries Arise Archive’ documents the last ten years of the ‘independent, rebellious’ London-based label. Founder Sofia Prantera tells Wallpaper* the story behind the project

By Jack Moss

-

Sarabande artists explore the creative potential of paper in ‘Bound’

Sarabande artists explore the creative potential of paper in ‘Bound’Bound is a book of paper artworks from 36 Sarabande artists that celebrates the arts and cultural foundation’s singular legacy. Director Trino Verkade shares the story behind the creation of this unique document

By Mary Cleary

-

Picture this! Jason Lloyd Evans' fashion show archive

Picture this! Jason Lloyd Evans' fashion show archiveThe British photographer shares his favourite backstage images, from the runway shows of Prada, Louis Vuitton, Balenciaga and more

By Laura Hawkins

-

New York's Venus Over Manhattan gallery casts rare works by Alexander Calder in a whole new light

New York's Venus Over Manhattan gallery casts rare works by Alexander Calder in a whole new lightBy Pei-Ru Keh