Contemporary artists explore slowness at Diadora's Pitti Uomo 95 exhibition

More than 1.8 billion photographs are taken every day. Our lives are broadcast as neat comic strips to an unrelenting schedule. Pictures and videos languish on hard drives and hover on digital clouds, untethered to any sort of reality. We go faster, forgetting to feel. For its 70th anniversary, the Italian sportswear brand Diadora commissioned five contemporary artists to contemplate speed in the modern world. The exhibition, It Plays Something Else, curated by Davide Giannella, is open at Stazione Leopolda in Florence as part of Pitti Uomo 95 this week. Each of the works on display has a timely focus on slowness.

From tennis to football, from running to cycling, Diadora has been at the forefront of the business of movement. Founded in 1948 on the heels of a climbing boot, each of its proceeding decades have been marked by the evolution of professional sports. The exhibition’s title refers to tennis player Ilie Năstase’s response at losing to Björn Borg at Wimbledon in 1976: ‘We play tennis, he plays something else.’

That ‘something else’ became a green light to the artists involved to create something personal. For British photographer Maisie Cousins it was ‘the opposite of speed.’ Her work gestures to modern-day tastes for sensual, broad narratives rooted in the female body. Her Untitled series capture the moments when the body is at rest after moving at a great pace.

‘I was interested in that time when you are sweating, your heart is going, there’s a clarity and a serenity to it that I like.’ Her pictures of surreal limbs jutting from pools of black water are haunting yet incredibly blithe. ‘I thought of Italian statues, which is so cliché but I liked that sense of the statuesque body that is sweaty. And it is still. I just wanted peaceful pictures,’ she says.

‘Manovia' by Patrick Tuttofuoco

Similarly, the Berlin-based artist Patrick Tuttofuoco was motivated by the manual processes he saw in the Diadora factory located in Montebelluna where around 150 pairs of shoes are handmade by artisans every day. Tuttofuoco was enthralled by processes that felt familiar to his own way of working. ‘I reflected on the concept of velocity, sport and action and also this very physical approach,’ he says. Much of his practice animates the duality between man and the machine.

His sculpture entitled ‘Manovia' is a colossal piece of Carrara marble 3D-sculpted into the shape of his own hands frozen, mid-stretch. Tuttofuoco has practiced the Japanese martial art of Aikido for many years and this pressing of the palms and folding back of the fingers is a gesture used to relax the body. The fine lines of his hands and the ripple of his nail beds are perfectly rendered using digital technologies – the patina of the process is left too as an affectionate reminder of how it has come into the world.

‘Technology makes things faster in every sense but still we need our hands to touch things, we need to be connected to reality, otherwise the idea of living will become difficult, trapped. The world is not flat,’ he says. ‘It is really deep!’

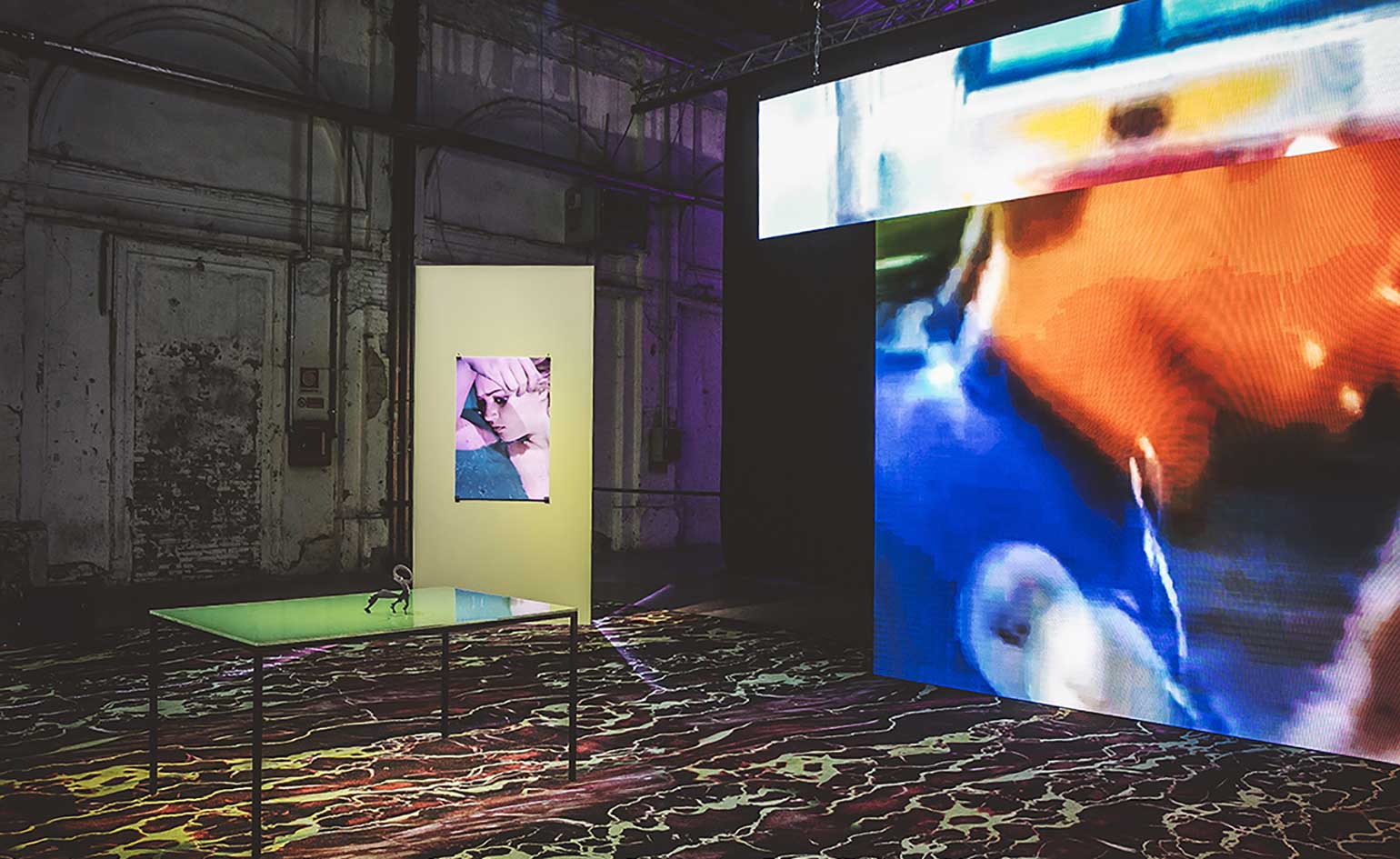

The show also features works by Invernomuto, which is made up of the duo Simone Bertuzzi and Simone Trabucchi. Since 2003 the pair have focused on moving image and sound, exploring what digital remains can be made of lost subcultures, and used this new commission to build on their series, Perspectives on Archives. They spent four months browsing the web and DVDs to find clips relating to the brand from the 1970s to the 1990s. These are played at varying speeds on two large screens, their shapes taken from sections of a typical tennis court in homage to Diadora’s history. ‘Building the archive was the first step and then we sampled it. Isolating the parts that made a complete picture,’ Bertuzzi says.

‘We are not demonising new media, it has created a new alphabet, a new language,’ Trabucchi says. ‘But it is complicated because when moving images are your work, you have the luxury of taking time to look at them for what they really are. We have time analyse them. You give them the possibility of being consumed for a longer time, or perceived in a different way to an endless, scrolling thing. You are taking them out of the web, creating a context to look at them in a different way.’

In the seventy years since Diadora made its first shoes, the volume of words, pictures and ephemera we now consume has increased with radical alacrity. The sports we play, the ground we walk on and what we wear on our feet are recorded over and over again, stored in digital archives for hazy public posterity. Yet as these works show, there is a genuine ambition to understand both what is lived and what is seen. ‘Technology is of course part of all of our processes but it should be something that you manage and not something that works us,’ Tuttofuoco says. ‘I feel a void between my physical body and the world we live in social media. There is a huge gap. Art can be that element that fills that.’

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Diadora website and the Pitti Immagine Uomo website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

London based writer Dal Chodha is editor-in-chief of Archivist Addendum — a publishing project that explores the gap between fashion editorial and academe. He writes for various international titles and journals on fashion, art and culture and is a contributing editor at Wallpaper*. Chodha has been working in academic institutions for more than a decade and is Stage 1 Leader of the BA Fashion Communication and Promotion course at Central Saint Martins. In 2020 he published his first book SHOW NOTES, an original hybrid of journalism, poetry and provocation.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

Edinburgh Art Festival 2023: from bog dancing to binge drinking

Edinburgh Art Festival 2023: from bog dancing to binge drinkingWhat to see at Edinburgh Art Festival 2023, championing women and queer artists, whether exploring Scottish bogland on film or casting hedonism in ceramic

By Amah-Rose Abrams

-

Last chance to see: Devon Turnbull’s ‘HiFi Listening Room Dream No. 1’ at Lisson Gallery, London

Last chance to see: Devon Turnbull’s ‘HiFi Listening Room Dream No. 1’ at Lisson Gallery, LondonDevon Turnbull/OJAS’ handmade sound system matches minimalist aesthetics with a profound audiophonic experience – he tells us more

By Jorinde Croese

-

Hospital Rooms and Hauser & Wirth unite for a sensorial London exhibition and auction

Hospital Rooms and Hauser & Wirth unite for a sensorial London exhibition and auctionHospital Rooms and Hauser & Wirth are working together to raise money for arts and mental health charities

By Hannah Silver

-

‘These Americans’: Will Vogt documents the USA’s rich at play

‘These Americans’: Will Vogt documents the USA’s rich at playWill Vogt’s photo book ‘These Americans’ is a deep dive into a world of privilege and excess, spanning 1969 to 1996

By Sophie Gladstone

-

Brian Eno extends his ambient realms with these environment-altering sculptures

Brian Eno extends his ambient realms with these environment-altering sculpturesBrian Eno exhibits his new light box sculptures in London, alongside a unique speaker and iconic works by the late American light artist Dan Flavin

By Jonathan Bell

-

![The Bagri Foundation Commission: Asim Waqif, वेणु [Venu], 2023. Courtesy of the artist. Photo © Jo Underhill. exterior](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/QgFpUHisSVxoTW6BbkC6nS.jpg) Asim Waqif creates dense bamboo display at the Hayward in London

Asim Waqif creates dense bamboo display at the Hayward in LondonThe Bagri Foundation Commission, Asim Waqif’s वेणु [Venu], opens at the Hayward Gallery in London

By Cleo Roberts-Komireddi

-

Forrest Myers is off the wall at Catskill Art Space this summer

Forrest Myers is off the wall at Catskill Art Space this summerForrest ‘Frosty’ Myers makes his mark at Catskill Art Space, NY, celebrating 50 years of his monumental Manhattan installation, The Wall

By Pei-Ru Keh

-

Jim McDowell, aka ‘the Black Potter’, on the fire behind his face jugs

Jim McDowell, aka ‘the Black Potter’, on the fire behind his face jugsA former coal miner, Jim McDowell defied the odds to set up his workshop and keep a historic form of American pottery alive

By Aruna D’Souza