The menswear designers celebrating the value of craft

We hone in on five menswear brands championing artisanal production

After months of human interaction umpired by computer screen, pleasure now lurks in the raw edges and amorphic patches applied with meticulous care to a vintage workwear jacket. This artisanal aptitude isn’t new – silk and cotton garments have been mended and patched together since the 17th century in Japan and, in North West Nigeria, indigo dye pits have been in operation for over 500 years – but it is enjoying a resurgence in menswear.

Many of the pre-industrial production methods employed by the five designers featured here are intrinsically sustainable and culturally profound. Evidence of the human hand takes on a more significant role at this unparalleled time: craft forces us to reconsider our own place in the world.

Harago

Each of India’s 32 states has its own artisanal legacy and Harsh Agarwal wants to revive every single one. His Jaipur-based menswear label Harago is a living, growing archive of indigenous crafts. ‘How I started was very random, I’ve always been passionate about clothing but I never thought of taking it up as a professional thing,’ he says. After graduating in economics from Pune’s Symbiosis School of Liberal Arts, Agarwal began working on a project with the United Nations, documenting traditional practices across the country. He made some clothes up for himself using the handloomed woven textiles he’d learned about and soon, family and friends took notice. ‘I never thought I’d start a label but I realised that there wasn’t much being done with menswear in India. People expect long tunics and narrow drawstring trousers in linen from us but we don’t really do that. I wanted patterns and shapes that were more experimental. With a little twist.’

A short-sleeved shirt in upcycled heavyweight cotton gauze with cross-stitched kittens at the pockets typifies his approach. ‘Over lockdown I was going through my grandmother’s old bed linens, handkerchiefs, table cloths and curtains and I came across so many kinds of embroideries that are now very rare. I wanted to find the artisans who could do them again and when I did, they were so intrigued. They were like, “WOW! We used to do this 40 years ago and nobody has asked for it since.” That’s when I realised why I was doing this.’

Prospective Flow

Prospective Flow was launched in Los Angeles in 2009 by three Japanese brothers with the founding motto: ‘Today is the future our ancestors dreamed of. Keep the heritage flowing.’ Daisuke, Yusuke and Kensuke Muramatsu are devoted to the concept of ‘Onko-chishin’, a Japanese expression meaning: the attempt to discover new ideas by studying the past through scrutiny of history. ‘There are a lot of things going on in the world right now – things are changing on a daily basis – and that’s why we need to maintain our concept even more,’ Daisuke says. ‘We still believe that the world is a better place today than it was in the past. The admiration of genuine products has been passed on from generation to generation.’

Their workwear-inspired clothes have a lived-in serenity. ‘Today, in the era of smartphones and social media, technology is evolving faster than ever. And although new technological advancements can be exciting, they can also become overwhelming. When it comes to garments that you are going to put next to your skin, people prefer the sense of warmth they can feel from something that’s made by hand.’

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘It’s become too easy to throw things out and replace them,’ the Los Angeles-based textile artist Adam Pogue says. He has created a line of limited edition French workwear jackets for Mohawk General Store’s in-house line Smock: ‘We came up with the idea to make back and elbow patches that I would sew onto the garments – essentially they were like tiny quilts. Each one unique. I’d cut into the jackets and repair them and the patchwork became more random.’.

Each vintage piece is appliqued with hand-dyed fabrics by Pogue and in true artisanal fashion, each wears its patina with pride. ‘They’re great because of the oil stains and wear and tear they’ve collected over the years which kind of gives a roadmap for each jacket to repair and reuse.’ Pogue who studied architecture and sculpture, first began crafting materials together to decorate his apartment, upholstering a sofa in Japanese boro-style. His serene constructivist collages champion a wider philosophy too: ‘If I can make something or repair something, (rather than buy something) then that’s what I’ll do.’

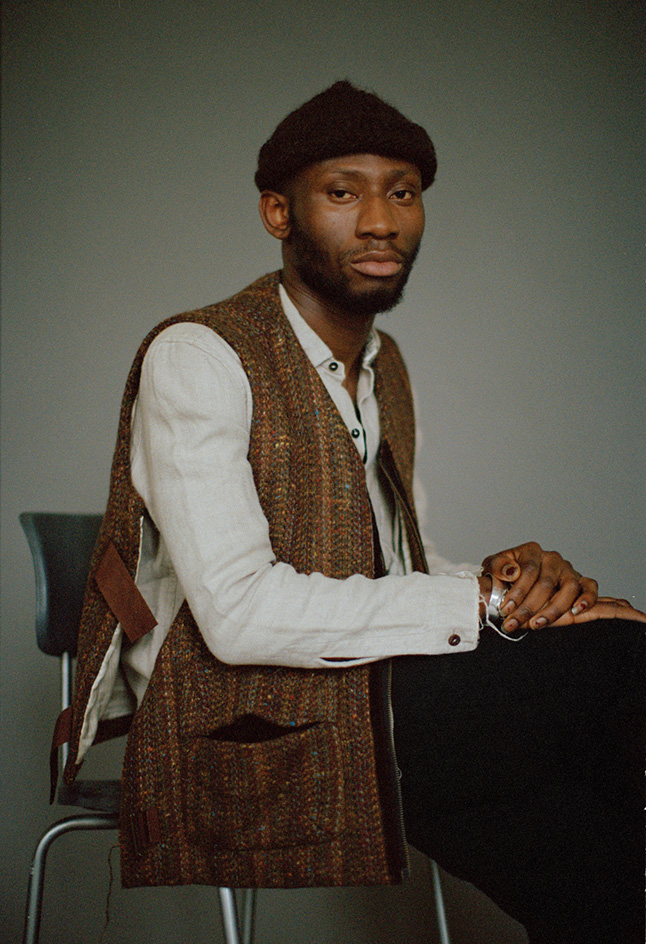

Monad London

RELATED STORY

Much of our perception of textile craftsmanship is oriented around the ancient techniques of Japan with less attention paid to the Kofar Mata dye pits in Kano, North West Nigeria. ‘I grew up in Nigeria so I had an implicit awareness of African textile crafts but I didn’t appreciate it until recently,’ designer Daniel Olatunji says. Hearing about the indigo traditions of his homeland whilst a student at Central Saint Martins in London, Olatunji moved back after graduating and set about learning as much as he could. His clothes – made using antique linens and homespun cottons – reflect a new feeling in menswear that refuses to be rushed.

‘I enjoy the process of making. I find it very meditative. The first time I saw the Fulani tribesmen in the north of Nigeria that grow and hand-weave cotton I was completely awestruck. The looms are built by the artisans using materials found around them and recycling parts from previous looms. This is also a reaction to my time working for more corporate and commercial brands where you see so much waste,’ he says. ‘Reviving and maintaining these processes can go some way to creating a more sustainable model for our industry. And our planet.’

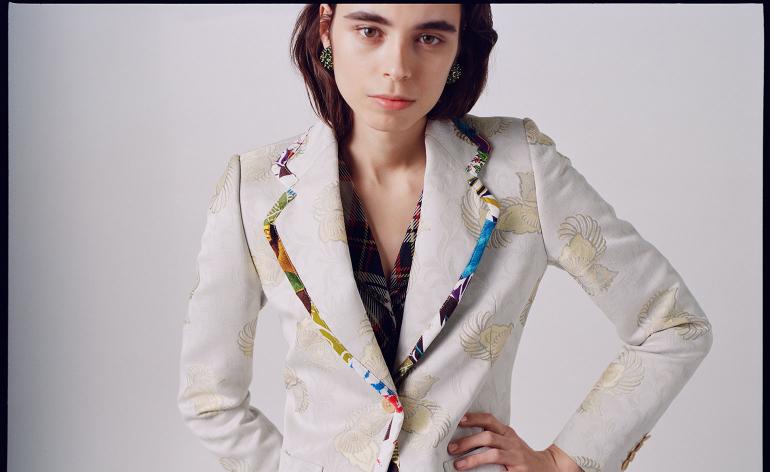

Koromo

With their opulent use of boro – the patchworking technique developed in the north of Japan during the Edo Period – the Kyoto-based label typifies how we often expect ‘crafted’ clothes to look. ‘Kyoto is a place where the making of clothes enters the field of fine arts,’ designer Kayoko Kondo says. ‘In our current world of advanced mechanisation, without the feeling of love, we can’t work tirelessly in same way as hundreds of years ago. What’s most important with clothing is first that you just love it and second, that you’ll live with it your whole life.’

When the label launched in 2004, Kyoto’s antique markets were stuffed full of elaborate antique kimonos, whilst old pieces of indigo-dyed cloth were thrown away. Now things are different: ‘Once I sewed some boro cloth together and made it into a jacket. I displayed it in my shop and many people gathered around, some frowning, some smiling, some criticising it loudly. It felt like being at one of the amusement parks I had gone to as a child!’ Kondo says. Now, there’s been a global shift to revisiting tradition: ‘Just as a wild stitch can be more attractive than a neatly aligned seam, the heart may throb more for rough nonconformity than for pristine fabric. Craftsmanship is a sensory realm.’ §

London based writer Dal Chodha is editor-in-chief of Archivist Addendum — a publishing project that explores the gap between fashion editorial and academe. He writes for various international titles and journals on fashion, art and culture and is a contributing editor at Wallpaper*. Chodha has been working in academic institutions for more than a decade and is Stage 1 Leader of the BA Fashion Communication and Promotion course at Central Saint Martins. In 2020 he published his first book SHOW NOTES, an original hybrid of journalism, poetry and provocation.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

Cult 1960s boutique Granny Takes A Trip gets a sustainable reboot

Cult 1960s boutique Granny Takes A Trip gets a sustainable rebootFounded on King’s Road in 1966, ‘radically creative’ fashion store Granny Takes A Trip is being reimagined for a new generation. Dal Chodha takes a closer look

By Dal Chodha

-

BITE Studios: ‘We want to have a brand which makes an impact’

BITE Studios: ‘We want to have a brand which makes an impact’BITE Studios is marrying sustainable textiles – from seaweed fabric to pea silk – with designs by a team including alumni of Proenza Schouler and Acne Studios

By Tilly Macalister-Smith

-

Icicle, the cross-continental label championing sustainability for 25 years

Icicle, the cross-continental label championing sustainability for 25 yearsOn the arrival of a new collection, ‘Hemp Up’, womenswear artistic director Bénédicte Laloux tells Wallpaper* the story behind minimally minded fashion label Icicle

By Jack Moss

-

Louis Vuitton announces decade long project to rewild London's Chelsea

Louis Vuitton announces decade long project to rewild London's ChelseaCentral London’s first ‘Heritage Forest' on Pont Street in Chelsea, will be the result of a rewilding partnership between Louis Vuitton, Cadogan and SUGi

By Laura Hawkins

-

Textile innovator Byborre empowers creators to cut waste

Textile innovator Byborre empowers creators to cut waste‘We developed a new process that allows creators to innovate,’ says Borre Akkersdijk, co-founder of Dutch textile innovation studio and clothing label Byborre

By Yoko Choy

-

Water inspires Holzweiler’s Snøhetta-designed Oslo flagship

Water inspires Holzweiler’s Snøhetta-designed Oslo flagshipHolzweiler Platz, the new retail destination of fashion brand Holzweiler in Oslo, is designed by architects Snøhetta as a naturalistic space that unites fashion, art and food

By Laura Hawkins

-

Marni Market arrives at Matchesfashion in Mayfair

Marni Market arrives at Matchesfashion in MayfairMatchesfashion is offering first access to its new Marni Market to Wallpaper* readers

By Laura Hawkins

-

Advene’s debut bag is forever

Advene’s debut bag is forever‘We want our debut bag to stand the test of wear, weather, and time’

By Laura Hawkins