Giorgio Armani’s top ten creative inspirations, from Eileen Gray to Issey Miyake

As part of his Wallpaper* October 2022 guest-edit, Giorgio Armani tells us about ten creatives that have inspired and energised him throughout his illustrious career

Wallpaper* October 2022 guest editor Giorgio Armani reflects on his top ten creative inspirations – among them Pierre Chareau’s architecture, Issey Miyake’s fashion, and Sarah Moon’s images of ‘tough delicacy’ – which have collectively shaped his vision of modernity.

Giorgio Armani on his creative inspirations

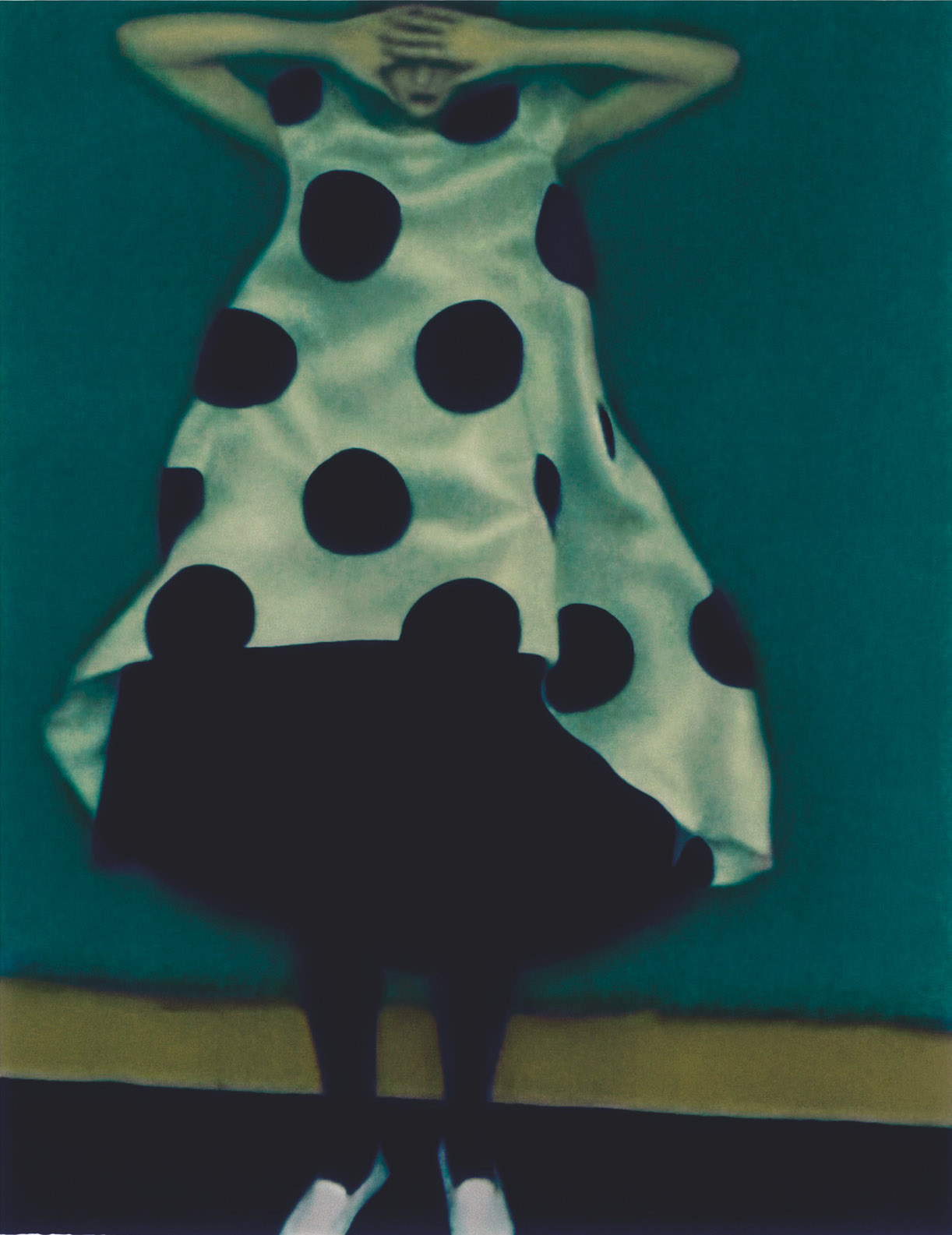

Sarah Moon

La robe à Pois, 1996, by Sarah Moon. Photography: © Sarah Moon, courtesy of Michael Hoppen Gallery

‘The years of my professional beginnings – the 1970s – are a time I remember not with nostalgia but with energy: the change was overwhelming and evident, and it ran through all segments of society. I myself was swept up in it, using my work to contribute to what was changing in the female world. Among the most interesting magazines of the time I remember Nova, which had a heavy focus on emancipation. I was particularly struck by the work of a young photographer who would later become my friend and whose work I would showcase at Silos: Sarah Moon. In her early shots, the mixture of romantic yearning and strength is striking. Sarah imagined a new woman, free of any preconceptions and belief systems, but who still managed to create an aura of magnetic fragility around her. That tough delicacy still inspires me today.’

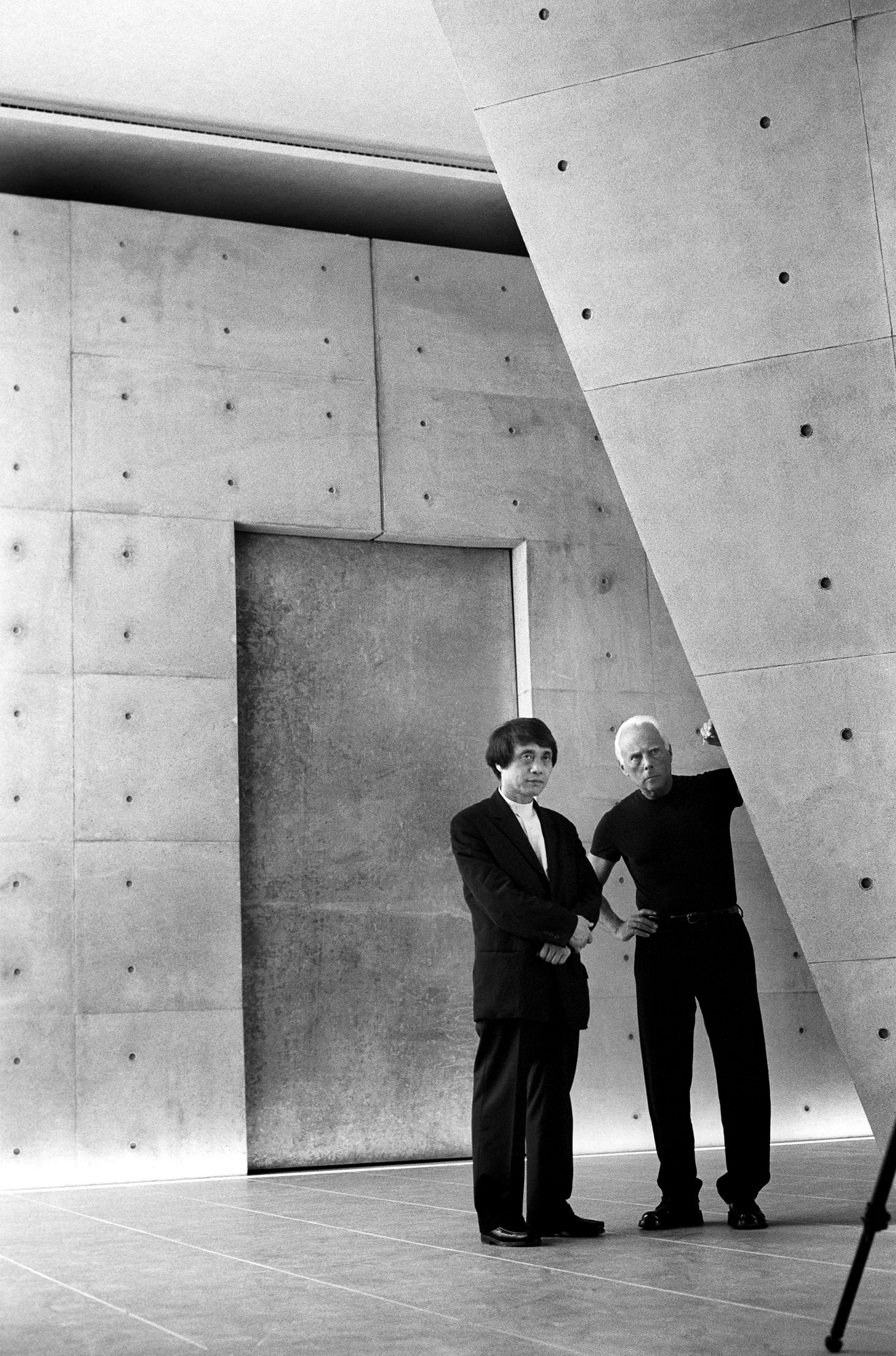

Tadao Ando

Ando and Armani photographed in 2001 at the launch of Armani/Teatro in Milan. Photography by Roger Hutchins, courtesy of Giorgio Armani

‘Tadao Ando is, in my opinion, the absolute master of contemporary architecture. His constructions made of solids and voids – in which the relationship with the environment and nature is always so important – seem to me to be the spatial transposition of haikus: like verses that associate words and ideas in a fulminating spirit of synthesis, Ando’s architecture resolves complex elements with the utmost compositional simplicity. I was able to appreciate his meticulousness and sensitivity first hand, having collaborated with him on Armani/Teatro. Tadao and I share a deep love for nature, which becomes absolute respect. His lesson is one of precision and dedication: like me, he is self-taught in a profession that has made him successful, and he has worked hard to make his visions a reality.’

Giorgio Morandi

Still Life, 1946, by Giorgio Morandi, currently on view at Tate Modern. Photography courtesy of Tate/DACS, 2020

‘To be part of something for yourself, to not join movements, to cultivate your own aesthetic without being tempted by the trifles of the moment: it’s a sort of calm, serene heroism that I learned from Giorgio Morandi, one of my favourite Italian artists. A heroism that I share. He is a truly extraordinary case of an isolated painter, with very little contact with other masters of the time. He is also an extraordinary case of an artist who practically painted almost exclusively the same subjects: bottles, vases, coffee pots, flowers, bowls and landscapes – always staying in the same room where he lived all his life. What touches me about Morandi is his palette: neutral and melancholic yet full of subtle, infinite modulations; and then his ability to simplify forms, to find just a few essential elements. His paintings are calm and reflective, both characteristics of the most exciting art.’

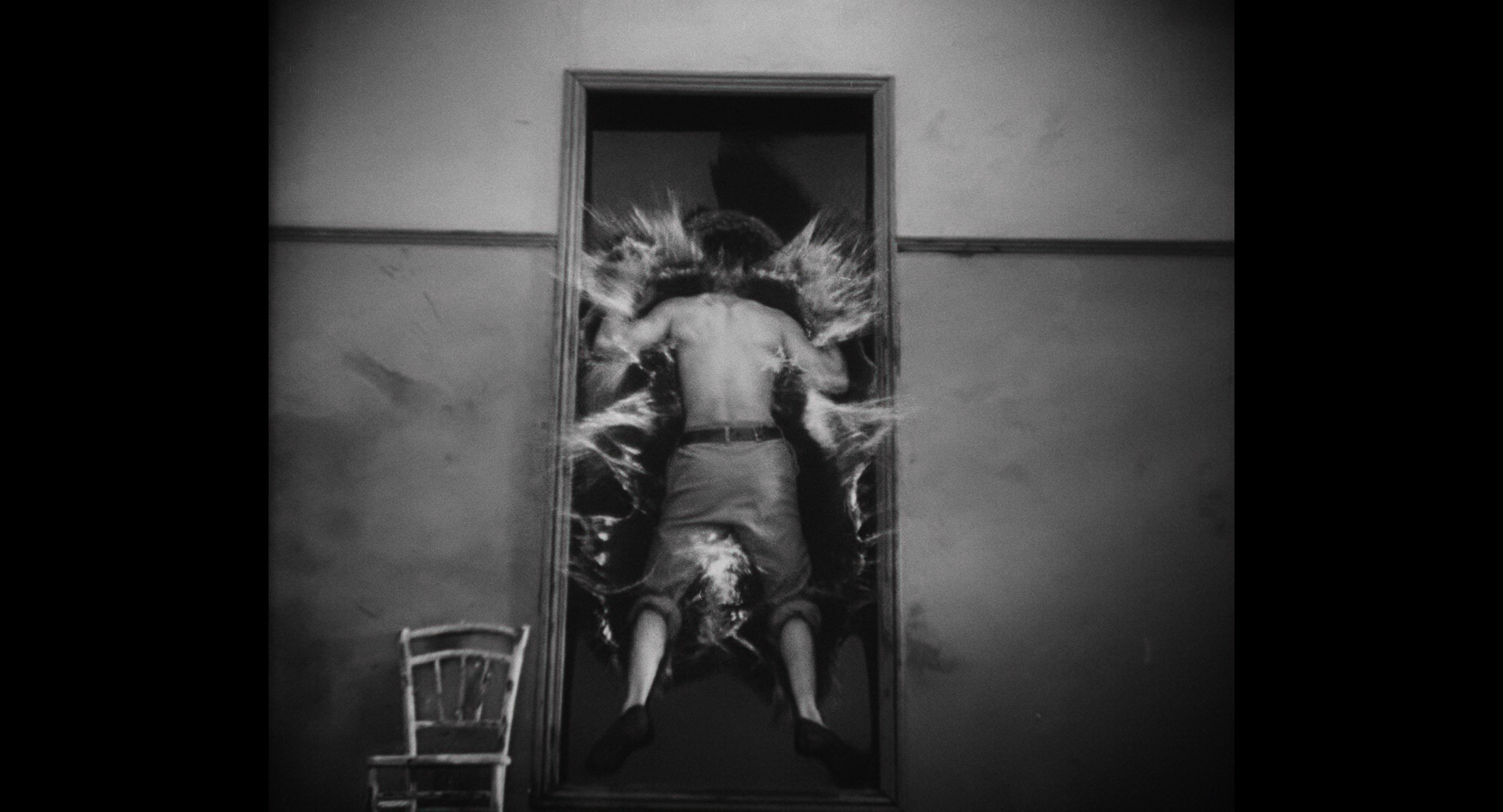

Jean Cocteau

Still from The Blood of a Poet, 1930, by Jean Cocteau. Film stills: © 1930 Studiocanal

‘Director, screenwriter, painter, playwright, writer, poet: I appreciate Jean Cocteau’s legendary yet almost elusive character. Everyone knows his name, but without linking it to a particular expression of his art. Many have read Les Enfants Terribles, some have seen The Blood of a Poet (1930) or Beauty and the Beast (1946); others are struck by his magnificent drawings, which are so simple yet erotic. I like his idea of ‘comprehensive art’, mixing words, painting, music and dance. He called everything, as a whole, ‘poetry’ – and this is no different from my way of understanding fashion, linking it to living and experiencing everything, to dwelling, and even to eating. I’ve always been struck by his sensitivity, his avant-garde style with roots in classicism, his ability to transport elements of the ordinary into different contexts to show them from another perspective.’

Pierre Chareau

The living room at Maison de Verre, Paris, built 1928-1932 for Annie and Jean Dalsace Photography by Mark Lyon

‘The modern movement profoundly marked the aesthetics of the 20th century, and Pierre Chareau was one of its pioneers. My favourite project of his – which is also his best known – is the Maison de Verre on Rue Saint-Guillaume in Paris, which he constructed in collaboration with Bernard Bijvoet and Louis Dalbet: a masterpiece of simplicity and modularity, with its translucent glass façade and various rooms that can be divided by sliding and rotating screens in glass, sheet metal and perforated metal. The fluidity of this space is truly astounding: an architectural design reminiscent of a mechanical ballet. What I admire about Chareau is his ability to give a new sense to the entire space with just a few movements, and also the fact that he is essentially famous for a single project.’

RELATED STORY

Coco Chanel

Coco Chanel photographed in her office in Paris in 1938. Photography by François Kollar, RMN-Grand Palais, 2022 © Photo Scala, Florence

‘The true fashion revolutionaries of the 20th century were all women, and I’m not surprised: a woman who creates women’s clothes has an understanding of their bodies, as well as of their roles, that a man can hardly achieve. I appreciate Jeanne Lanvin as much as Madeleine Vionnet and Elsa Schiaparelli, but my favourite remains Coco Chanel, whom I consider the inventor of a modern way of dressing and thus, by translation, of the contemporary woman. The liberation of the female wardrobe started with her, and this should not be forgotten. From Chanel, I learned the importance of the material, and to drop all preconceptions: her famous jersey jackets were, in fact, initially made from the same fabric as men’s underwear. Here, this freedom is a great stimulus, a great inspiration. Add on top of that the ability to synthesise; in other words, to work with just a few colours and a few details, reiterated with the utmost subtlety.’

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Jean-Michel Frank

The New York apartment designed by Jean-Michel Frank for Nelson Rockefeller in 1938. Photography by Ezra Stoller/ESTO, courtesy of Rockefeller Foundation

‘Jean-Michel Frank’s ability to speak to modernity and timeless classicism is unrivalled. His interior design exemplifies the absolute absence of the superfluous, the focus on the essential. It remains unparalleled for me. His style was so pure that it deserved the definition ‘luxury of the mind’, and was a true celebration of empty space in an era when excessive grandeur, overloaded environments, and formulaic Baroque-ism predominated instead. To call him a minimalist, however, would not be doing him any justice. Frank certainly loved whites and neutrals, but his work was multidimensional, with an absolute focus on matter. I find his idea of subtraction infinitely inspiring and, from a personal point of view, I also admire the fact that he wore a grey suit as a uniform, just as I do with my blue T-shirt.’

Issey Miyake

A Cicada Pleats outfit from Issey Miyake’s S/S89 collection. Photography by Albert Watson

‘Clothes like flying saucers, dresses cut from a single piece of fabric, bridges stretched between the ancestral past and the galactic future, and then the ever-inventive use of pleating: Issey Miyake’s work was full of poetry, and it tended towards a constant search for functionality – an aspect on which not all designers focus today. I’ve never hidden my passion for Japanese designers, for their quest for simplicity, for their always progressive and fresh vision of the relationship between clothing and the body. Miyake is the one I feel the closest to, specifically because of his attention to people. The clothes he created only come to life once they are worn, and they change from one person to another, following their way of being and behaving. This is what I myself try to do, because I never forget that if the first thing you notice about a person is their clothes, then the designer has made a mistake.’

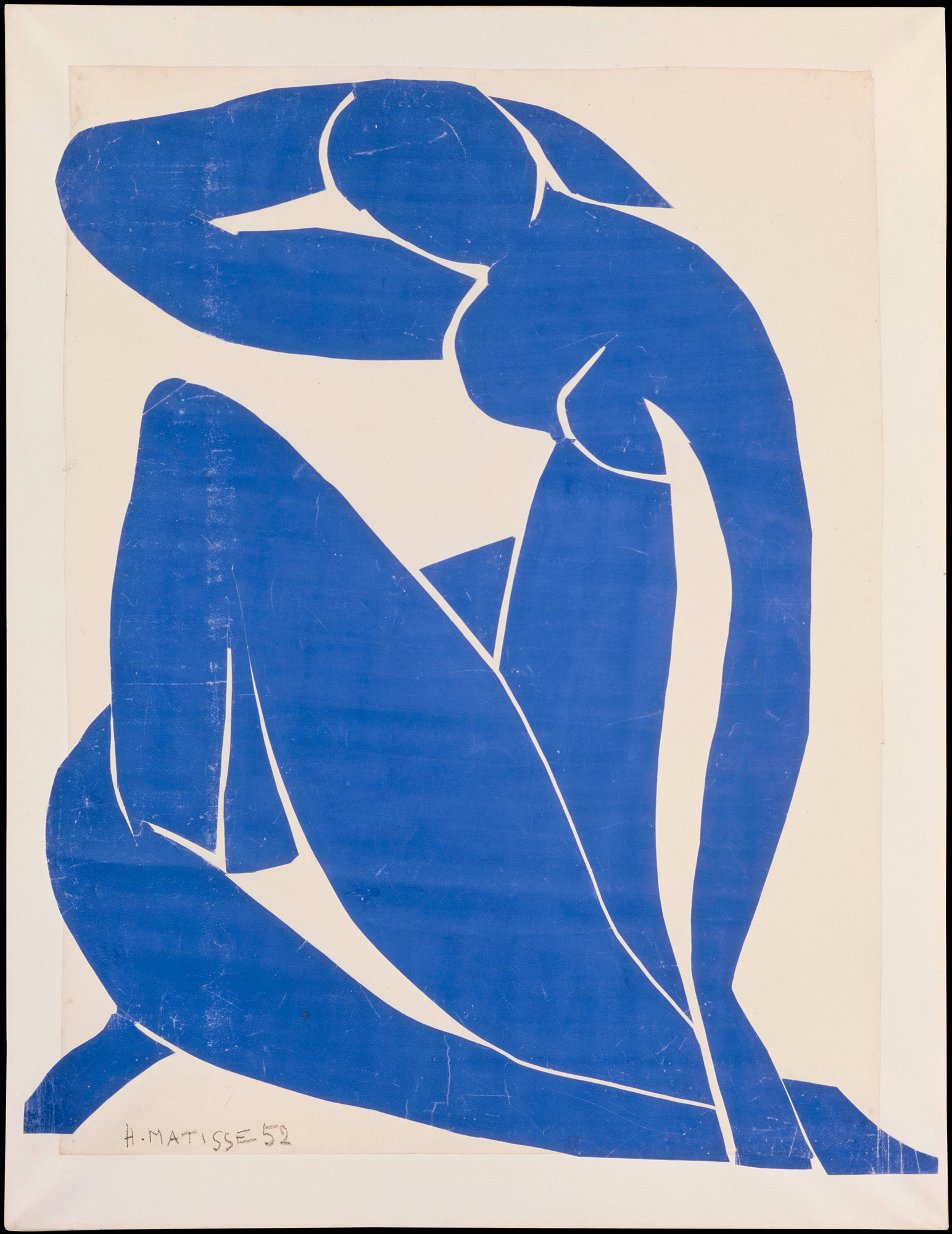

Henri Matisse

Nu Bleu II, 1952, by Henri Matisse. Photography by Image Centre Pompidou MNAM-CCI, RMN-Grand Palais, 2022 © Photo Scala, Florence

‘Shape, colour, immediacy: Henri Matisse’s Blue Nudes, a series of collages made with paper cut-outs, is an incredible example of the spirit of synthesis that characterises great artists. These are works in which rhythm and sensuality are magnetic, with a touch of blue that makes them electrifying. I find it particularly inspiring that this joyful, triumphant ode to life was created by Matisse when he was already an old man, using scissors instead of a paintbrush. Instead of surrendering to physical decline, he found inspiration and renewed energy in his art, creating brilliant, striking and large works. A thought in which I find myself today more than ever: creativity truly has no age.’

Eileen Gray

Eileen Gray’s E 1027 villa (1926-1929) sits below Le Corbusier’s Unités de Camping (1955-1957) on the French Riviera. Photography by Benjamin Gavaudo/Centre des monuments nationaux © Eileen Gray/Jean Badovici/Fondation Le Corbusier–ADAGP

‘A mysterious trailblazer, Eileen Gray was an elusive figure, both as a woman and as a designer. Even Le Corbusier looked up to her. I often think of her unique way of designing spaces and the elements that adorn them. She used a pure yet never cold language that gave absolute prominence to matter. But I also think of the free way she experienced femininity. This came back to mind recently because the Galerie Jean Désert, which she had opened in Paris with Jean Badovici, was opposite the Salle Pleyel, where I showcased my Privé collection. From her, I learned the balance between solids and voids, between curves and straight lines: the ‘Bibendum’ chair and the ‘E 1027’ coffee table are unforgettable in this sense, as is the E 1027 maison en bord de mer in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, a masterpiece of balance and surprise.’

INFORMATION

A version of this article appears in the October 2022 issue of Wallpaper*, available in print, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today!

-

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuit

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuitElla Kruglyanskaya’s exhibition, ‘Shadows’ at Thomas Dane Gallery, is the first in a series of three this year, with openings in Basel and New York to follow

By Hannah Silver

-

Australian bathhouse ‘About Time’ bridges softness and brutalism

Australian bathhouse ‘About Time’ bridges softness and brutalism‘About Time’, an Australian bathhouse designed by Goss Studio, balances brutalist architecture and the softness of natural patina in a Japanese-inspired wellness hub

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Marylebone restaurant Nina turns up the volume on Italian dining

Marylebone restaurant Nina turns up the volume on Italian diningAt Nina, don’t expect a view of the Amalfi Coast. Do expect pasta, leopard print and industrial chic

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Loafer bags to sock shoes, 2024 was all about the mashed-up accessory

Loafer bags to sock shoes, 2024 was all about the mashed-up accessoryWallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss reflects on the rise of the surreal hybrid accessory in 2024, a trend which reflects the disorientating nature of contemporary living – where nothing is quite what it seems

By Jack Moss

-

The Wallpaper* S/S 2025 trend report: ‘A rejection of the derivative and the expected’

The Wallpaper* S/S 2025 trend report: ‘A rejection of the derivative and the expected’Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss unpacks five trends and takeaways from the S/S 2025 shows, which paid ode to individual style and transformed the everyday

By Jack Moss

-

Le Sel d’Issey: the sacred ‘energy of salt’ inspires Issey Miyake’s new fragrance for men

Le Sel d’Issey: the sacred ‘energy of salt’ inspires Issey Miyake’s new fragrance for menAs Issey Miyake’s Le Sel d’Issey launched in Tokyo this week, we spoke with Tokujin Yoshioka about his ‘radiant’ bottle design and the scent's sacred and salty inspiration

By Danielle Demetriou

-

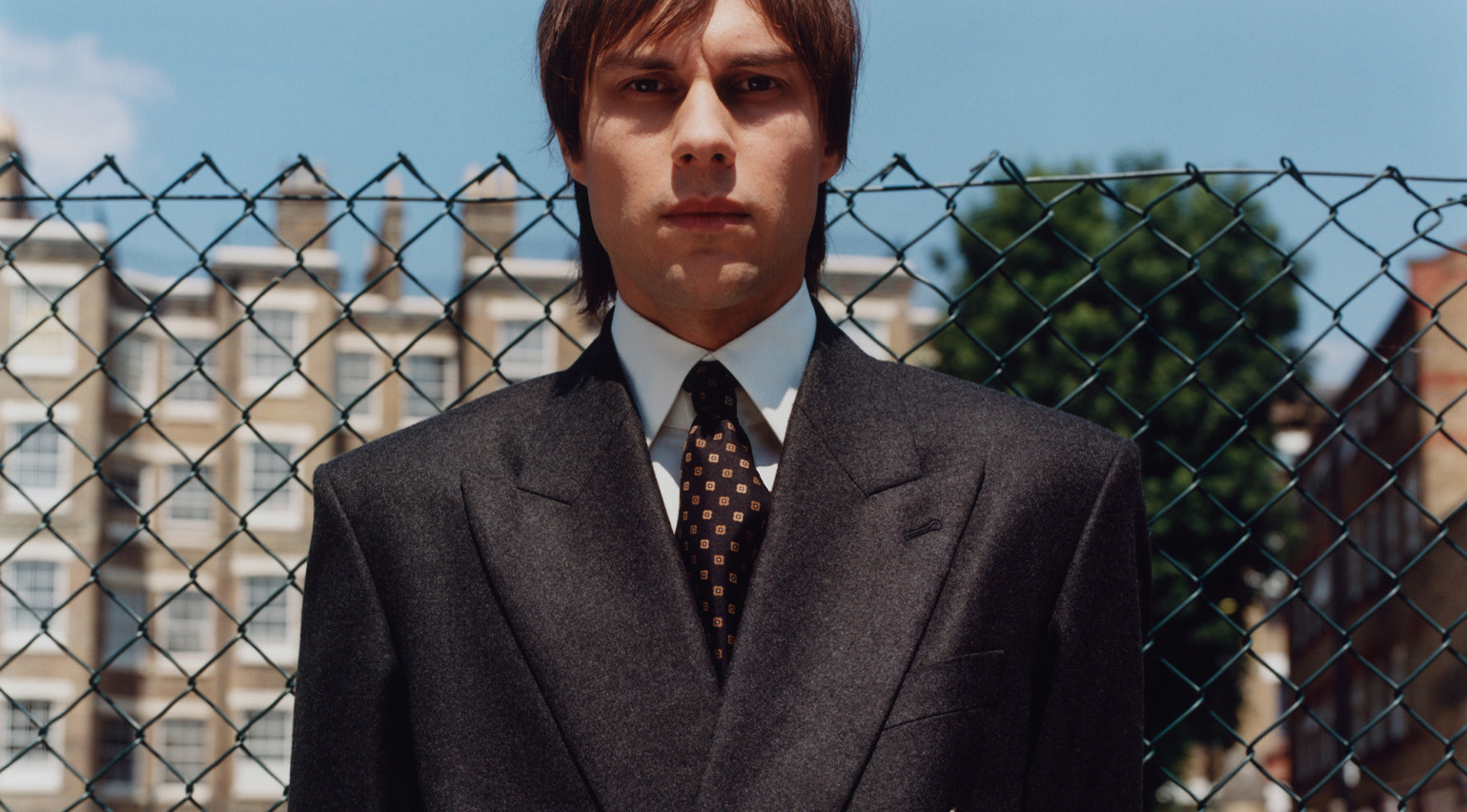

The A/W 2024 menswear collections were defined by a ‘new flamboyance’

The A/W 2024 menswear collections were defined by a ‘new flamboyance’Sleek and streamlined ensembles imbued with a sense of performance take centre stage in ‘Quiet on Set’, a portfolio of the A/W 2024 menswear collections photographed by Matthieu Delbreuve

By Jack Moss

-

‘There is a renewed desire to be elegant’: why men’s tailoring is more relevant than ever

‘There is a renewed desire to be elegant’: why men’s tailoring is more relevant than everFar from a dying art form, men’s tailoring is gaining momentum thanks to a diverse array of designers who are using the garment to change the way we move and feel, says Simon Chilvers

By Simon Chilvers

-

In fashion: the defining looks and trends of the A/W 2024 collections

In fashion: the defining looks and trends of the A/W 2024 collectionsWe highlight the standout moments of the A/W 2024 season, from scrunched-up gloves and seductive leather ties to cocooning balaclavas and decadent feathers

By Jack Moss

-

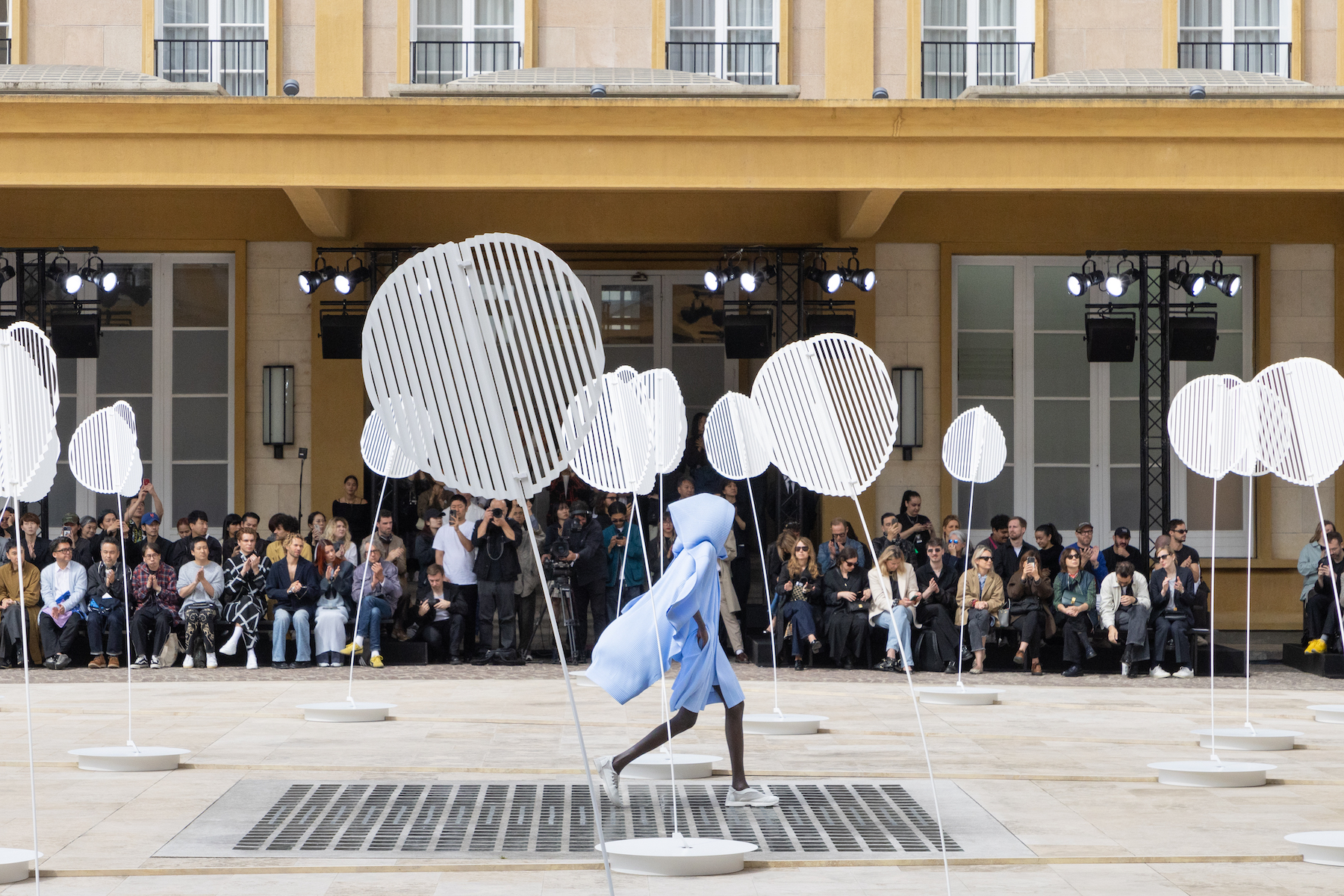

Revisiting the showstopping runway sets of men’s fashion week

Revisiting the showstopping runway sets of men’s fashion weekAs Men’s Fashion Week S/S 2025 draws to a close, Wallpaper* picks the season’s most transporting runway sets, from giant cats at Dior Men to a ‘fairytale ravescape’ at Prada

By Jack Moss

-

Milan Fashion Week Men’s S/S 2025 highlights: Prada to Zegna

Milan Fashion Week Men’s S/S 2025 highlights: Prada to ZegnaWallpaper* picks the best moments from Milan Fashion Week Men‘s S/S 2025, from 15 years of MSGM to Prada’s celebration of youth, and an appearance from Mads Mikkelsen at Zegna

By Jack Moss