Lately, Anna Zegna has been spending more time in her 100 sq km garden. Well, not exactly her garden, so much as that of the Italian textile giant and menswear brand Ermenegildo Zegna. The brand’s founder, Anna’s grandfather, opened his mill back in 1910, when he was just 18 years old, and he later began planting what would come to be known as the Oasi Zegna. A public idyll around Trivero, the Oasi is now home to many a fruit, herb and leaf that another of the garden’s fans, Zegna’s artistic director Alessandro Sartori, has used to provide the dyes for a cashmere collection launching later this year. Remarkably, it’s not all beige.

‘Just a few years ago, all you could do without using chemical dyes were the lighter shades – and there was a lot of beige,’ says Sartori. ‘You’d start out with, say, this beautiful deep red and, by the time you’d washed the garment, 90 per cent of that colour was gone. But now there are ways of fixing the colour – rich purples from iris, camels from teas – by a process of repeated dip-dyeing. We’ve even managed to fix black, which is the real challenge. It all uses a lot of water, but at least there are no chemicals.’

The result, says Anna, president of Fondazione Zegna, is the kind of interesting idea only likely to appeal to a more connoisseur customer, not least because the process is expensive: it adds around 10 per cent extra to the cost of a cashmere piece, but would add around 50 per cent to the likes of a woollen jacket, the kind of thing which may come later. ‘It’s a fascinating story, though, because it’s about a real relationship to the land, to history,’ she says.

History is a big thing for Ermenegildo Zegna. As was typical of early Italian industrialists, the family home was built cheek-by-jowl with the manufacturing plant, so young Anna and her siblings played in the garden to the sound of the factory whistle. But this year also marks the 50th anniversary of its move into ready-to-wear, after almost six decades supplying suit fabrics to tailors.

Ermenegildo had long encouraged a spirit of progressiveness in the family firm – when most textiles manufacturers wholesaled their cloths and remained largely anonymous to the end customer, he insisted on the company name being woven into the selvedge. His money was also behind Italy’s first men’s style magazine and he established international competitions to ensure access to the finest wools. But his sons, Angelo and Aldo, didn’t want to risk throwing that good name away and the first generation of off-the-peg suits were sold under a new brand name, with the association with Zegna only introduced slowly. ‘Like any new job, you don’t get to grips with it on the first day,’ jokes Anna.

That caution was wise: it’s hard to imagine now when, as Sartori puts it, ‘men have never had so much choice or interest in what to wear,’ but Zegna’s step into ready-to-wear – providing three cuts of suits loosely targeted at three age ranges, the fits resulting from wide anthropomorphic studies – was a first for Italian men. Until then, a good suit meant a visit to a tailor – and as tailors were the Zegna company’s bread and butter, not upsetting them with this vision of future fashion was a consideration, too.

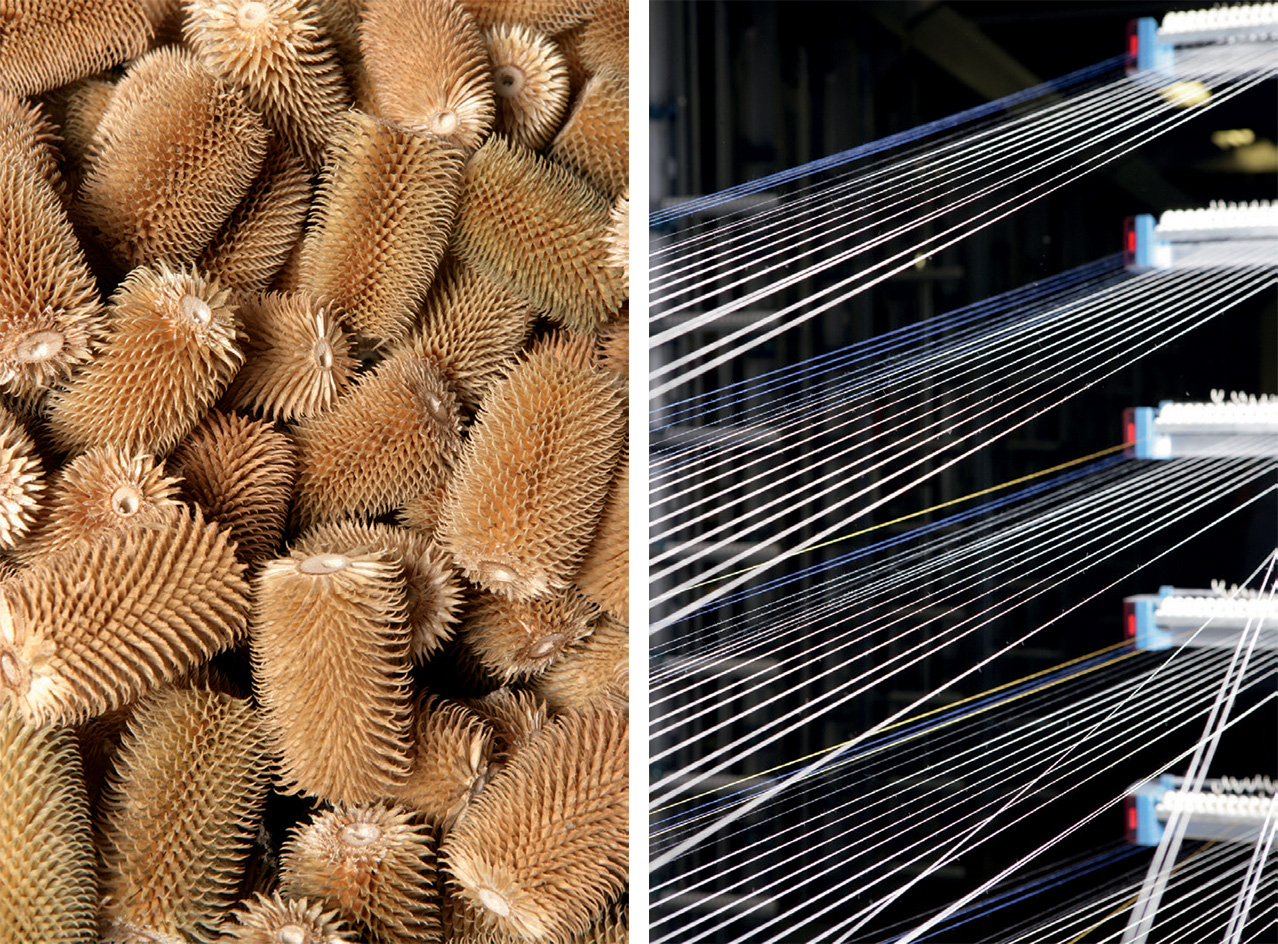

A fabric rests before being finished.

‘Ready-to-wear presented a great opportunity but also a great challenge, not least because the 1960s and 1970s were politically and socially very difficult years for Italy,’ says Anna. ‘The ideas seemed radical. We did a trousers-only line called Cantara and, until then, trousers were only worn as part of a suit. We wanted to present them as a product in their own right, that you interpreted according to your own style. We had to do a lot of explaining as to how each pair could be part of your lifestyle. And this time was revolutionary rather than evolutionary in that it was really when the idea of creating a distinctively Italian lifestyle came to the fore – Italian clothes, cars, design, Ettore Sottsass, Brionvega. It wasn’t just a matter of style. It was sociological, a matter of concern to philosophers. The likes of Umberto Eco were writing about it. It was when the Italian fashion story started – a few years later, all the designers started to come through.’

Anna Zegna might well remember: she was head of PR for Gianni Versace – enjoying the pizzazz and the chance, as a woman, to actually wear the clothes she represented – before her father called her back into the fold to play her part in the family firm’s next chapter. (‘I asked if I could stay at Versace for one more year, but he said no,’ she recalls.)

Of course, while Ermenegildo Zegna continues to supply other designers – it produces around 1,000 different cloths every year, or around 12,000 if different colour variations are counted – and even, behind the scenes, to produce a lot of their tailoring, these days it’s ranked more as one of them. All the more so given the recent push towards a brighter, more upbeat, more casual and more complete conception of its menswear. Earlier this year, the company acquired Cappellificio Cervo, one of Italy’s historic hat-makers, as well as – of all things – a leather string manufacturer. Sartori has designed an accessories line for the coming autumn/winter using it. No vest is included.

‘When you look at menswear now, there’s a lot of crazy styling, some of which is not so easy to like,’ says Sartori, who grew up in the region around Trivero and recalls seeing the Zegna name everywhere he went on his bicycle. ‘But the fact is that, such are the changes in attitudes among men to the way they dress, that even streetwear brands are our competitors now. Zegna has had to undergo something of a transformation. And that doesn’t mean just creating some kind of marketing story, but also thinking of relevant ways of doing things.’

By way of example, Sartori returns to the new cashmere, with its emphasis on natural processes and sustainability – what might sound like green-washing were it not for the fact that Ermenegildo Zegna can genuinely claim a track record in corporate social responsibility that’s much older than the zeitgeisty phrase. Today, it still puts 5 per cent of its profits into environmental and educational causes – and given that it’s now a company with an annual billion euro-plus revenue, that’s not to be sniffed at. It’s a reminder that, for all that its cloths are crafted and its tailoring crisp, ultimately it’s about big business.

‘I think the company’s most important contribution to menswear over that 50 years, over its history, has been its achievement of total verticalisation – the fact that the family controls what it does from the sheep to the shop,’ says Anna. ‘That level of integration isn’t easy to do, but it really improves the products. And it allows you to move forward by building on what’s gone before without having to rely on anyone outside of the chain. That doesn’t make Ermenegildo Zegna a brand that’s all about heritage. But it does, I think, give it meaning.’

As originally featured in the September 2018 issue of Wallpaper* (W*234)

Yarn is spread out to create the warp – the vertical axis of the fabric.

Left, natural teasels are used to brush Zegna’s range of fabrics to create a soft finish. Right, the dyeing stage.

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Ermenegildo Zegna website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Josh Sims is a journalist contributing to the likes of The Times, Esquire and the BBC. He's the author of many books on style, including Retro Watches (Thames & Hudson).

-

How Stephen Burks Man Made is bringing the story of a centuries-old African textile to an entirely new audience

How Stephen Burks Man Made is bringing the story of a centuries-old African textile to an entirely new audienceAfter researching the time-honoured craft of Kuba cloth, designers Stephen Burks and Malika Leiper have teamed up with Italian company Alpi on a dynamic new product

-

Valie Export in Milan: 'Nowadays we see the body in all its diversity'

Valie Export in Milan: 'Nowadays we see the body in all its diversity'Feminist conceptual artists Valie Export and Ketty La Rocca are in dialogue at Thaddaeus Ropac Milan. Here, Export tells us what the body means to her now

-

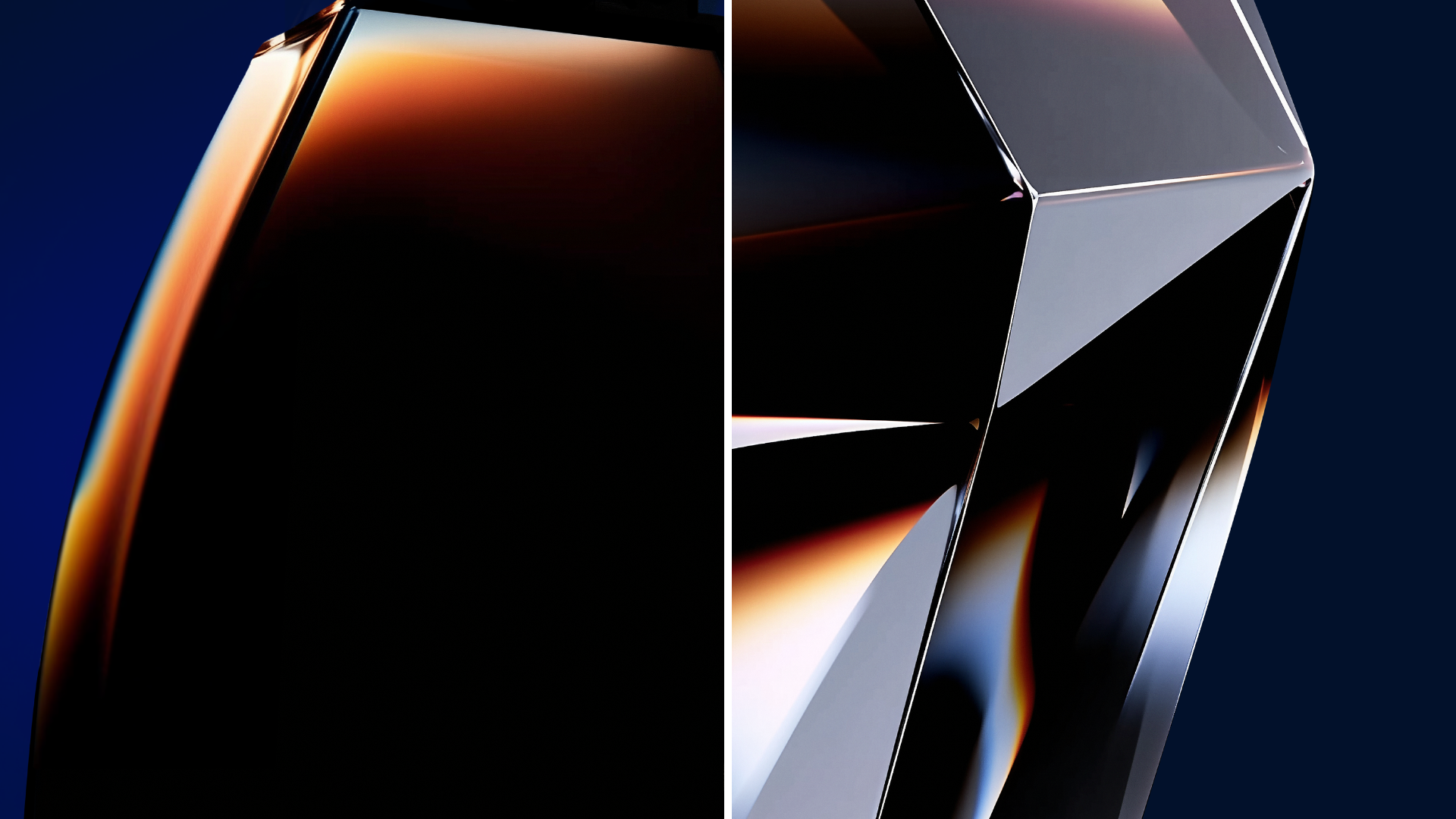

Martell’s high-tech new cognac bottle design takes cues from Swiss watch-making and high-end electronics

Martell’s high-tech new cognac bottle design takes cues from Swiss watch-making and high-end electronicsUnconventional inspirations for a heritage cognac, perhaps, but Martell is looking to the future with its sharp-edged, feather-light, crystal-clear new design

-

‘He made something not merely popular, but the rage’: unpacking Elio Fiorucci’s fabulous fashion legacy

‘He made something not merely popular, but the rage’: unpacking Elio Fiorucci’s fabulous fashion legacyAn expansive new retrospective at Triennale Milano explores the colourful life and work of Elio Fiorucci, who is synonymous with 1970s hedonism and glamour

-

‘What does a Luca Faloni jacket look like?’: this suede bomber marks the brand’s first foray into outerwear

‘What does a Luca Faloni jacket look like?’: this suede bomber marks the brand’s first foray into outerwear‘Made for years to come’, this lightweight bomber marks Luca Faloni’s entry into outerwear and encapsulates the label’s provenance-focused approach

-

Rovi Lucca is the Milanese label creating ‘elevated workwear for garden lovers’

Rovi Lucca is the Milanese label creating ‘elevated workwear for garden lovers’Rooted in Italian craft, Bradley Seymour and Fabrizio Taliani’s horticulturally inspired Rovi Lucca finds inspiration in the gardens of Lucca, Tuscany

-

Luca Magliano takes Wallpaper* on a tour Bologna, the home of his non-conformist fashion label

Luca Magliano takes Wallpaper* on a tour Bologna, the home of his non-conformist fashion labelLuca Magliano gives Wallpaper* an insider’s guide to Bologna, Italy, the lifeblood of his on-the-rise label – from a museum of queer history to a mystical cemetery (and plenty of gelato)

-

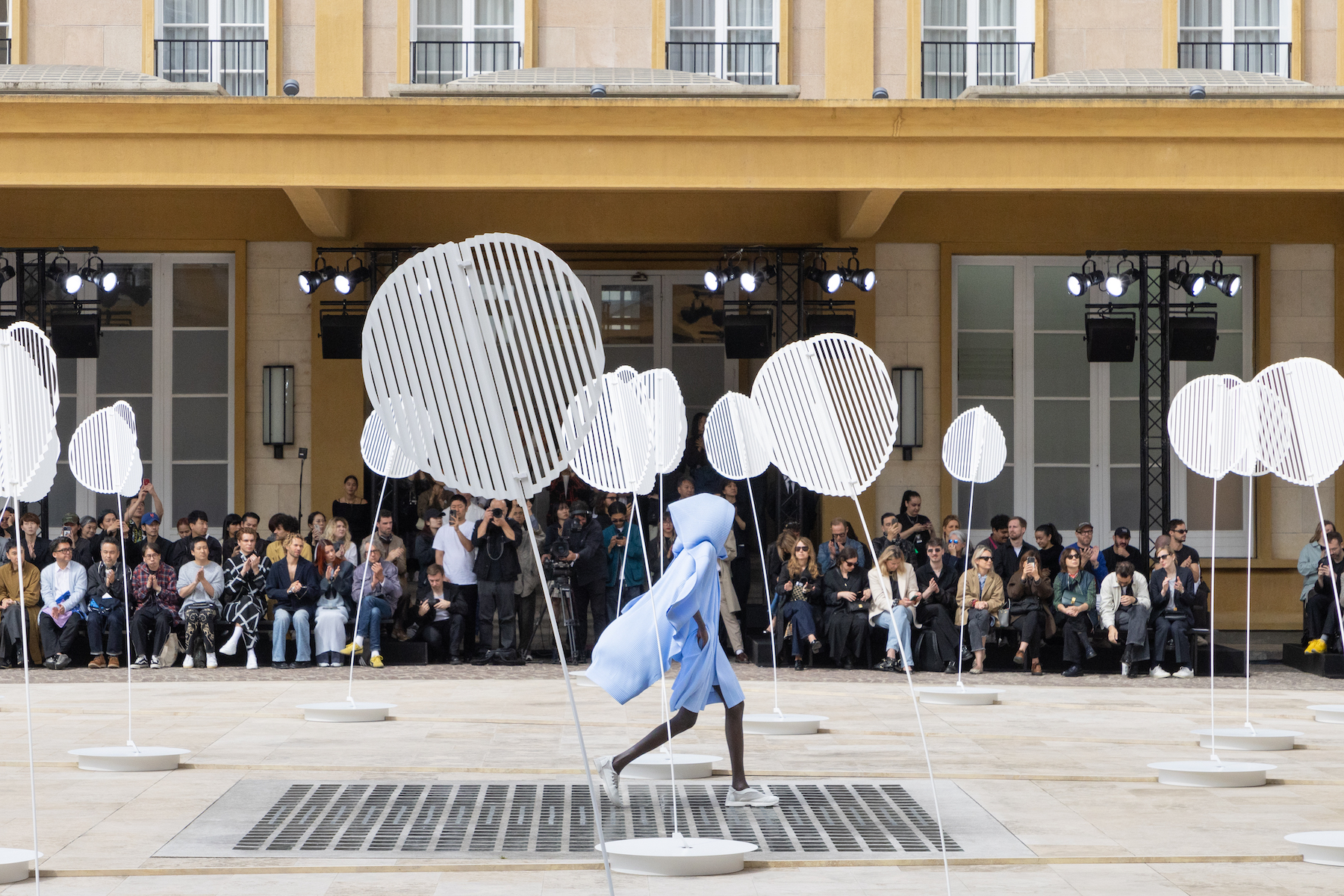

Revisiting the showstopping runway sets of men’s fashion week

Revisiting the showstopping runway sets of men’s fashion weekAs Men’s Fashion Week S/S 2025 draws to a close, Wallpaper* picks the season’s most transporting runway sets, from giant cats at Dior Men to a ‘fairytale ravescape’ at Prada

-

Utilitarian men’s fashion that will elevate your everyday

Utilitarian men’s fashion that will elevate your everydayFrom Prada to Margaret Howell, utilitarian and workwear-inspired men’s fashion gets an upgrade for S/S 2024

-

Men’s Fashion Week S/S 2025: what to expect

Men’s Fashion Week S/S 2025: what to expectBeginning this weekend, everything we know about Men‘s Fashion Week S/S 2025 so far, from Dries Van Noten’s final show in Paris to an intimate Craig Green presentation in London

-

Zegna’s innovation-filled ‘Secondskin’ sneaker began with a pair of leather gloves

Zegna’s innovation-filled ‘Secondskin’ sneaker began with a pair of leather glovesZegna’s ‘Triple Stitch Secondskin’ sneaker sees the Italian house experiment with glove leather for a lightweight shoe, designed to mould to the contours of the foot