Modern Times: furniture giant RH is remodelling the US design scene

Most homeware retailers just want to sell as many beds, sofas, chairs and rugs as they can. Gary Friedman is a furniture maker who wants to change the world, one Afghan pouffe at a time. ‘We all have our own authentic light. And if we shine our authentic light, it can lift the spirit of another human being and inspire them to shine their light on others,’ he says. ‘Our goal is to create an endless reflection of hope, inspiration and love that will ignite the human spirit and change the world. We believe by chasing our hopes and dreams, we can inspire others to chase theirs.’

Listening to his evangelical corporate woo-woo while studying his permatanned complexion and wrists striped with woven bracelets inscribed with the mottos ‘Believe’ and ‘Live and let live’, it’s tempting to dismiss Friedman as a West Coast entrepreneur who has spent too much time in the California sun. But that would be a mistake, because he is transforming the way we play house.

Friedman rebooted Restoration Hardware – or RH as it is now known – as the world’s first large-scale upmarket furniture and homeware retailer. That might not sound like a big deal, but it is. While fashion companies have sold clothes and accessories in large branded stores all over the world for years, fancy furniture retailers are largely boutique operators, such as B&B Italia and Zanotta in Italy and The Conran Shop or Heal’s in Britain. Not Friedman. He sells a full range of furniture to suit an upscale lifestyle – thousands of items in dozens of variations – and he does it in the kind of stores that would make Sir Terence Conran, Habitat founder and Docklands property pioneer, weep with envy.

RH’s new shops, or ‘next-generation design galleries’ as Friedman prefers to call them, are up to 70,000 sq ft freestanding department stores with different sections for interiors, lighting, bath, bed, small spaces, linens, rugs, outdoor, baby and child, and teen. The most striking are located in converted historic buildings with architecture and construction budgets running into the tens of millions of dollars. The vast windows open to let in the sun and the fresh air. There are roof terraces with 100-year old olive trees, restaurants and cafés, and valuable modern art on the walls. ‘We are obsessed with great architecture,’ Friedman says. ‘We either find it or we build it.’

RH sells mainly reinterpreted classics in a muted colour palette of stone, brown and greige. Now Friedman is going in a bold new direction, by launching the largest range of higher-end modern home furniture and furnishings ever made.

Any day now, the new RH Modern source book – no mere ‘catalogue’ – will thud on to doormats all over America. It’s the size and weight of a small child. On the front will be a slender yet bold RH Modern logo, crafted by Fabien Baron. Inside will be homeware created by designers, artisans and craftsmen and women from around the world. Key pieces include the ‘Cloud’ sofa by Timothy Oulton, the ‘Boule de Cristal’ chandelier by Jonathan Browning and the ‘Smythson Shagreen’ platform bed by Van Thiel. ‘We have a very small internal design team. We prefer to seek out those designers whose work we admire and give them a platform to make and sell more pieces than they ever imagined possible,’ Friedman says.

This approach is RH’s secret sauce. By finding good stuff and scaling up production, Friedman can keep prices lower than his competitors. It works. When Friedman took over RH in 2001 it had a market value of $20m. It’s now worth almost $4bn. The share price has increased nearly four-fold since the firm floated in 2012. Earnings have grown more than 25 per cent in all of the past 12 quarters. Average RH retail store sales have increased from $2.9m on his watch to more than $10m, taking total sales to $2bn a year – a figure Friedman hopes to double with the launch of RH Modern and the new stores. To put that figure in perspective, the turnover of big-name Italian furniture retailers is more like a few hundred million dollars a year.

The RH Modern source book will be backed up by a new standalone RH Modern gallery in LA; RH Modern floors in the firm’s next-generation design galleries, opened in Chicago and coming soon to Denver, Tampa and Austin; and one floor of RH’s Flatiron store in New York. ‘We’ll add 100,000 sq ft of retail space for RH Modern every year,’ Friedman says. The total investment in the new brand, which he describes as ‘our best work to date’, is thought to exceed $50m.

But why move into modern now? ‘To succeed in retail at scale, you have to be fresh, yet familiar. You need to think until it hurts so you can see what others can’t see, so you can do what others can’t do, re-evaluate all the time, to remain unfinished and on the move, otherwise customers get bored. We needed to evolve,’ he says. The time is right to pare down to a cleaner, edgier aesthetic because ‘modernism is more meaningful to people now than at any other time and it is only going to get more meaningful. Modern architecture has never been more fashionable,’ he points out. He cites the acclaim heaped on the likes of Zaha Hadid, Frank Gehry, Jean Nouvel, Renzo Piano, Norman Foster, Richard Rogers and Herzog & de Meuron.

‘We consume modern products with almost evangelical zeal, mainly Apple devices,’ he adds. ‘We work in modern office buildings and increasingly live in modern or wannabe-modern homes. Young people, who make their first purchase, prize modernity and, increasingly, so do their parents, the baby-boomer generation. People are living longer and no-one wants to grow old surrounded by old things. Even people who want to retire don’t want to grow old. It’s part of a broader trend towards youth, wellness and wellbeing.’

Macro-economic trends also point to a vast new global market for homeware. ‘Cities are growing faster than ever. Not just existing cities, like London. New cities are springing up with homes for hundreds of millions of newly affluent people – in China, Africa and the Middle East. Humanity is becoming more urban and more modern.’ If Friedman snags even 0.01 per cent of this new urban market, he will add to his $400m fortune and become the most influential – and wealthiest – upscale furniture retailer in history.

That would be all the more remarkable because, unlike many other homeware entrepreneurs in Europe and America, he did not grow up surrounded by the finer, softer things in life, dreaming that one day he could create a business that felt like home. In fact, he grew up with almost no furniture at all. ‘We only had one table, which was a coffee table that my mother, Angelina, used to freshen up by covering with different types of adhesive paper. It would be fake wood grain one year and then fake marble the next year. We ate off a small kitchen “dinette” table and had a small sofa but that was it.’

The Friedmans were poor – and troubled. Friedman’s father died aged 42, when Gary was only five years old. Angelina was in and out of hospital. ‘We moved 21 times in the first 18 years of my life, living of welfare and food stamps.’ It may have been tough but it has made him what he is and RH is today. ‘After my father died I had big abandonment issues and grew up a really insecure kid. It made me want to try harder, to be the best at everything. I used to hit tennis serves against the wall for hours because I wanted to be the best tennis player in the school team. I did the same later for basketball.’ After dropping out of Santa Rosa Junior College in his first year, he took his zeal and commitment to work. In 1976, he got a job at Gap as a stock boy. Millard Drexler, the retail entrepreneur who went on to make J Crew what it is today, joined Gap in 1983 when Friedman was a store manager in San Francisco and the two men hit it off. The boss set him on a meteoric trajectory, from that role to the company’s youngest-ever regional manager, running 63 stores in Los Angeles. He was 29. Williams-Sonoma, America’s largest home-grown kitchen and homewares outfit, took notice and made him ‘an offer I couldn’t refuse’: running all Williams-Sonoma’s stores.

He transformed Williams-Sonoma, adding demonstration kitchens, food halls and tasting bars. He also transformed Williams-Sonoma’s Pottery Barn brand from a tabletop company generating $50m a year to a $1.2bn-a-year brand. Total company sales for Williams-Sonoma rose from $300m a year to $2.1bn. He was promoted to president and chief operating officer. The firm’s then CEO, Howard Lester, assured him he would succeed him. But when the big day came, Lester gave the job to another older, external executive. Friedman had share options worth $50m provided he stuck at the firm but he decided to quit and took over Restoration Hardware. He had wanted to buy it when he was running Williams-Sonoma but the board said no. The firm was worth just $20m and at death’s door. ‘We had to raise money three times in the first year to dig it out of the grave.’ It wasn’t hard to see why. It sold a mixture of novelty items – garden gnome-shaped lawn sprinklers inspired by the film The Full Monty – and essentials – toasters and tool kits. ‘It had no focus,’ he says, pulling out an old catalogue from his bag and laughing.

But the brand had equity that Friedman thought he could use to develop his vision of a mass upscale home furnishings brand. He sunk $4.5m of his own money into the firm, raised tens of millions more, and set about finding designers to create the collections he thought America wanted – all created and curated in a headquarters in Corte Madera, just over the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco, which is now the 120,000 sq ft RH Center for Innovation and Product Leadership.

While many retailers have turned their back on bricks and mortar in favour of online sales, Friedman believes consumers will flock to his stores as long as they look and feel like the kind of homes they aspire to live in. He also eschews digital marketing in favour of splashy public events, often based around contemporary art. ‘We are a physical product company, not a digital one,’ he says. He commissioned and acquired the first edition of Rain Room by Random International and loaned the artwork to the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where it drew crowds around the block, as it did when it was shown at the Barbican in London. ‘Even if art never becomes a very big business, it renders the brand more valuable. That’s what you want to do with marketing, right?’ he says. It’s tempting to think that Friedman has devoted so much time to redefining the furniture market simply to prove to Williams-Sonoma that they made a huge strategic blunder in passing him over for the top job. He admits that he was hit hard by that decision: ‘I was devastated.’ But he insists he is not motivated by a desire for corporate revenge. ‘It haunted me for a good five years but that’s all gone now. It’s been gone for years.’

Friedman’s story is remarkable by any standards. But that doesn’t mean he is without his critics. Those who want to see American brands sell more Made In America products point out that almost everything that RH sells is made overseas in low-wage economies. Analysts warn that creating a long-term successful new business on the scale Friedman is attempting is risky. ‘RH has had the magic touch in its core collection,’ says Brad Thomas, an analyst at KeyBanc Capital Markets. ‘The questions now are: how will RH Modern appeal to those core customers and how many new customers will it pull in? We don’t know that yet, but the initial response within its Outdoor line has been positive.’ Some observers worry that he will be distracted by his embrace of contemporary art, his decision to set up a music label, his aim to expand into fashion and architectural services, and his plans to open a boutique hotel in New York in 2016.

Friedman is characteristically bullish in his response to the charges against him. ‘We’re naive. That’s a good thing. It means we don’t know what can’t be done. It also means I’m going to make mistakes.’ He is seeking to make more products in America. ‘It’s early days but manufacturing is coming back.’ He concedes that the current collection is ‘a bit one note’. But he insists RH Modern will change that. ‘Don’t pigeon-hole us based on what you see today. You have not seen our best work yet. What’s coming is more innovative, impactful and meaningful than anything we’ve ever done.’ His business model and a five-year plan that he recently presented to the board is, he says, ‘the most aspirational in the history of my career’.

And if consumers still don’t like RH after Modern is launched, ‘Well, tell them: “You don’t have to shop here. Go shop somewhere else!”’ he laughs. He can afford to because, on the evidence so far, they won’t.

As originally featured in the November 2015 edition of Wallpaper* (W*200)

RH Chairman and CEO Gary Friedman at the company's HQ

RH celebrated RH Modern on Fifth Avenue in New York's Flatiron District last week.

RH Modern offers a curated selection of modern furnishings, lighting and decor with a minimal, contemporary aesthetic. Courtesy RH

From the collection, from left: 'Marcel' floor lamp; 'Marble Plinth' table; brass bowl, from a selection; 'Seagram' dining table; 'Smythson Shagreen' sideboard; bowl, as before.

RH Modern introduces a new design language to the RH world that builds on minimalist design and comfort in a range of warm and cool tones. Courtesy RH

'Deane' tufted chaise.

Lighting from the collection.

Many of the RH Modern collections have been developed in collaboration with respected designers, such as Ben Soleimani and José Gandía-Blasco, and reissues of midcentury originals from Milo Baughman. Courtesy RH

'Courchevel' fireplace tools.

'Khan' chair.

RH Chairman and CEO Gary Friedman says, 'From antiques to architecture, from the environments we work in to the devices we work with, there is a modern sensibility that is influencing what we see and how we live in the world.' Courtesy RH

INFORMATION

For more information visit RH Modern

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

16Arlington’s Marco Capaldo on ‘turning up the volume’ with an A/W 2025 collection rooted in 1980s cinema

16Arlington’s Marco Capaldo on ‘turning up the volume’ with an A/W 2025 collection rooted in 1980s cinemaRevealed at an intimate dinner at London Fashion Week, 16Arlington designer Marco Capaldo found inspiration for an amped-up A/W 2025 collection in David Lynch’s ‘Blue Velvet’, Wim Wenders’ ‘Paris, Texas’ and Robert Palmer’s ‘Addicted to Love’ video

By Jack Moss Published

-

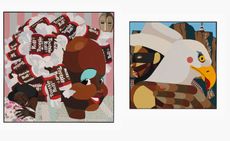

High low culture and the sickly sweetness of Tootsie Rolls: Derrick Adams in London

High low culture and the sickly sweetness of Tootsie Rolls: Derrick Adams in LondonDerrick Adams plays with themes of Black Americana in ‘Situation Comedy’ at Gagosian London.

By Hannah Silver Published

-

Lamborghini, fast friends with the Italian State Police for two decades

Lamborghini, fast friends with the Italian State Police for two decadesWhen the Italian police need to be somewhere fast, they turn to a long-running partnership with one of the country’s most famed sports car manufacturers, Lamborghini

By Shawn Adams Published