Embellishing an empire: a new exhibition puts Napoleon’s jeweller in the spotlight

Heritage-jewellery exhibitions are proving a top draw at museums across the globe. But then, rare jewels bring wonder, history, high glamour, jaw-dropping skills and, for some, a twitch of schadenfreude with them – they also symbolise the rise and fall of faded dynasties. Chaumet’s current exhibition Chaumet in Majesty: Jewels of Sovereigns, then, delivers on all fronts. Here’s our highlights.

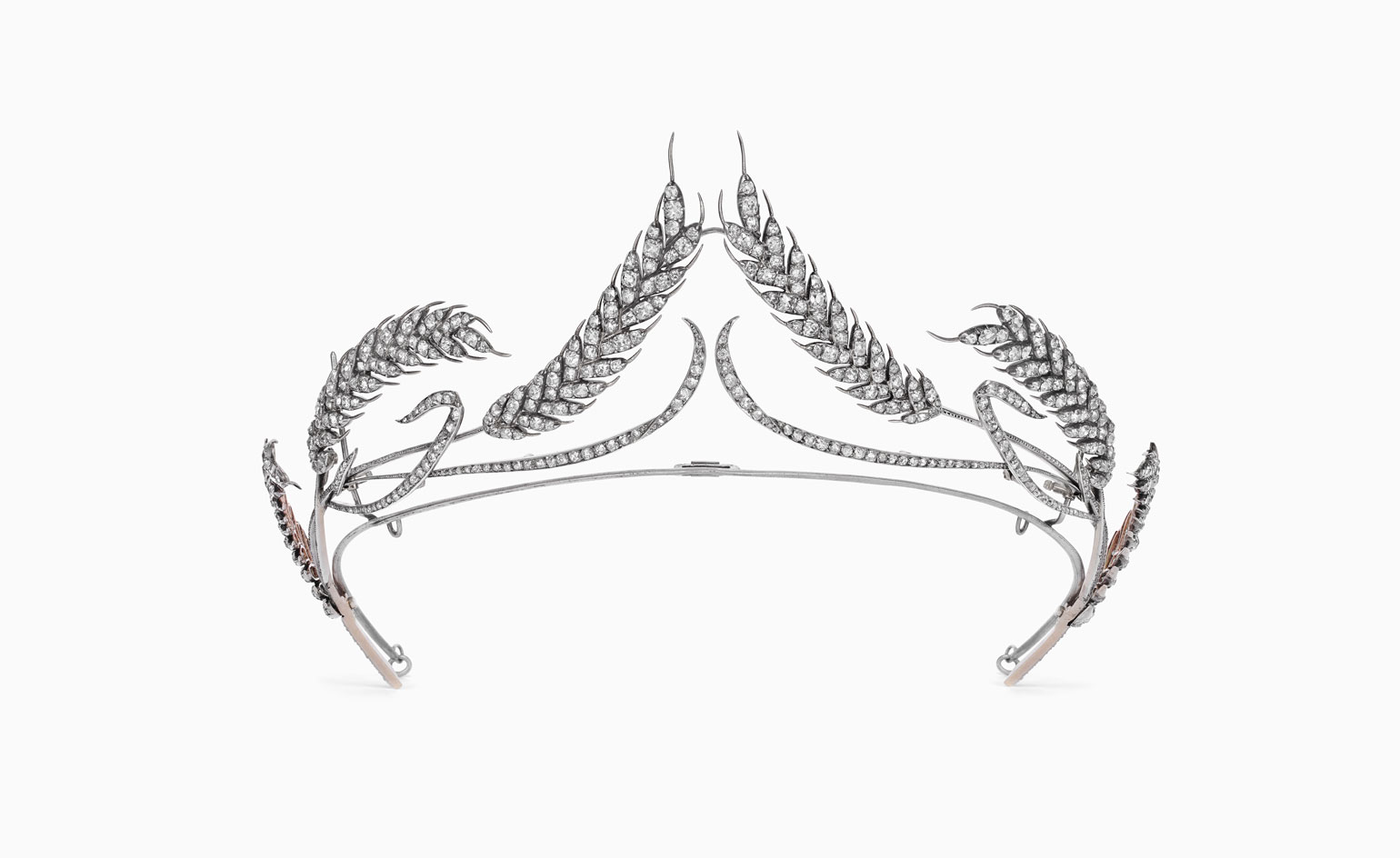

‘Crèvecoeur’ tiara

Chaumet captured the market in tiara design from the moment the founder, jeweller Marie-Étienne Nitot, became jeweller to Napoleon. Nitot, a die-hard royalist had a canny instinct for embellishing the Imperial aspirations of his client – Napoleon and Josephine both adopted his tiaras as power symbols. Centuries of tiara designs make up a sizeable portion of the 250 pieces on show. Here, the tiaras are endowed the status of ‘cult’ jewel. But that seems trite, a curator’s clunky modern spin, because this intimate view reveals tiaras as miniature works of art and architecture, a lasting homage to the sheer artistry and engineering skills of the dedicated Place Vendôme jewellers who sculpted and set them.

Ear of wheat, or ‘Crèvecoeur’ tiara, in gold and diamonds. 18th-century design by François-Regnault Nitot, adapted by Joseph Chaumet a century later

Hair comb

While many of the exhibition jewels are loaned by private collectors, Chaumet owns studio replicas, also made by the house-founder Nitot, of pieces from a parure for Napoléon’s second wife, Marie-Louise of Habsburg-Lorraine, Archduchess of Austria and grand-niece of Marie-Antoinette. This exquisite comb was part of a set of designs in oriental rubies and diamonds, including a tiara, coronet, necklace, drop earrings and bracelets. It was delivered to the empress in 1811.

Comb, in gold, silver, white sapphires, zircon and garnets. Designed by François-Regnault Nitot

Briar rosebud tiara

By the early 20th century, the tiara had been set free from royal circles and tradition to become a covetable fashion accessory for new societies with money to spend on status symbols. Tiaras were popular during the Belle Epoque period, when romantic motifs, such as bows and stars, were common design hooks. By the 1920s, Jazz Age socialites infused them with a pop sensibility, finishing off sleek, silk gowns with decadent tiaras at society parties. Today, a new kind of lavish lifestyle has sparked demand once again. “The tiara has very much enjoyed a revival since the beginning of the 2000s,’ confirms exhibition co-curator, the jewellery historian Christophe Vachaudez. ‘Workshops at jewellery maisons are continuously undertaking special orders.’

Tiara, in platinum, diamonds and pearls. Designed by Joseph Chaumet, circa 1922

‘Vertiges’ tiara

‘When Chaumet commissioned Central Saint Martins student Scott Armstrong to design ‘a tiara for our times’ in 2017, he imagined a light structure of criss-crossing straight and curved lines that was inspired by the geometric grids particular to French formal garden design. Its name – ‘Vertiges’ – refers to aerial shots of these gardens and, Armstrong says, ‘the lightheadedness experienced with vertigo.’ The designer subverted the romantic floral motifs that also play a key role in Chaumet’s canon, such as bouquets of hydrangeas and stalks of wheat.’ – Laura Hawkins

Tiara in white gold, with pavé and channel-set white diamonds, with green tourmalines and yellow garnets.

‘Chaumet in Majesty' exhibition runs until 28 August at the Grimaldi Forum, Monaco

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Caragh McKay is a contributing editor at Wallpaper* and was watches & jewellery director at the magazine between 2011 and 2019. Caragh’s current remit is cross-cultural and her recent stories include the curious tale of how Muhammad Ali met his poetic match in Robert Burns and how a Martin Scorsese Martin film revived a forgotten Osage art.

-

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial site

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial siteWe tour the Xingfa cement factory in China, where a redesign by landscape specialist SWA Group completely transforms an old industrial site into a lush park

By Daven Wu

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Chaumet’s new book celebrates its most memorable collaborations with photographers

Chaumet’s new book celebrates its most memorable collaborations with photographers'Chaumet: Photographers’ Gaze' unites jewellery editorials and campaigns captured by major photographers. Co-author Carol Woolton tells us of the ‘addictive' Chaumet archive

By Hannah Silver

-

Chaumet, Cartier and Chanel up their high jewellery watch game for 2024

Chaumet, Cartier and Chanel up their high jewellery watch game for 2024In 2024's high jewellery watch designs, performance tech and centuries-old techniques combine to brilliant effect

By Caragh McKay

-

High jewellery with dazzling effects

High jewellery with dazzling effectsStand-out gems dazzle against a backdrop of red and black in our high jewellery shoot

By Hannah Silver

-

Paris 2024 and Chaumet unveil Olympic and Paralympic medals

Paris 2024 and Chaumet unveil Olympic and Paralympic medalsThe Paris 2024 Olympic and Paralympic medals designed by Chaumet are not just emblems of champions but are storytelling jewellery

By Minako Norimatsu

-

Chunky chains are given a subversive high jewellery spin

Chunky chains are given a subversive high jewellery spinHigh jewellery houses rewrite the rules by way of 1980s tunes and a blast of emeralds, spinels and diamonds

By Caragh McKay

-

Year in review: top 10 watch and jewellery stories of 2023, as picked by Wallpaper’s Hannah Silver

Year in review: top 10 watch and jewellery stories of 2023, as picked by Wallpaper’s Hannah SilverSilver’s top 10 watch and jewellery stories of 2023 span cool horological collaborations, sculptural forms, and cutlery as bracelets

By Hannah Silver

-

Chaumet exhibition celebrates the golden age of jewellery design in Paris

Chaumet exhibition celebrates the golden age of jewellery design in ParisA Chaumet exhibition, ‘Un Âge d’Or’, in Place Vendôme, puts jewellery designs from 1965 – 1985 in the spotlight

By Hannah Silver

-

Chaumet’s high jewellery nods to naturalistic traditions

Chaumet’s high jewellery nods to naturalistic traditionsChaumet presents its new high jewellery collection in four chapters

By Hannah Silver