Ocean Liners at the V&A Museum explores the history of transatlantic seafaring design

Welcome to a huge, overbearing concoction of glittering surfaces, richly embellished craft and careful attention to everything from the biggest object right down to the tiniest detail. This is the V&A’s new blockbuster, ‘Ocean Liners: Speed and Style’, a suitably grand evocation of the golden age of one of history’s most venerated forms of transport.

‘Ocean Liners’ taps into many of our contemporary fascinations and obsessions, including glamour, nationalism, class, art, design, sex and death. The liner represented the apogee of the first industrial age, a floating city of unparalleled sophistication built on the raw power of shipbuilding and steam. The very best artists, designers, architects, craftspeople and stylists were employed to shape these vessels, pouring themselves into every last conceivable detail, from curtains to cutlery, while the industrial might of nations ground out the iron, steel and millions of rivets that shaped each boat.

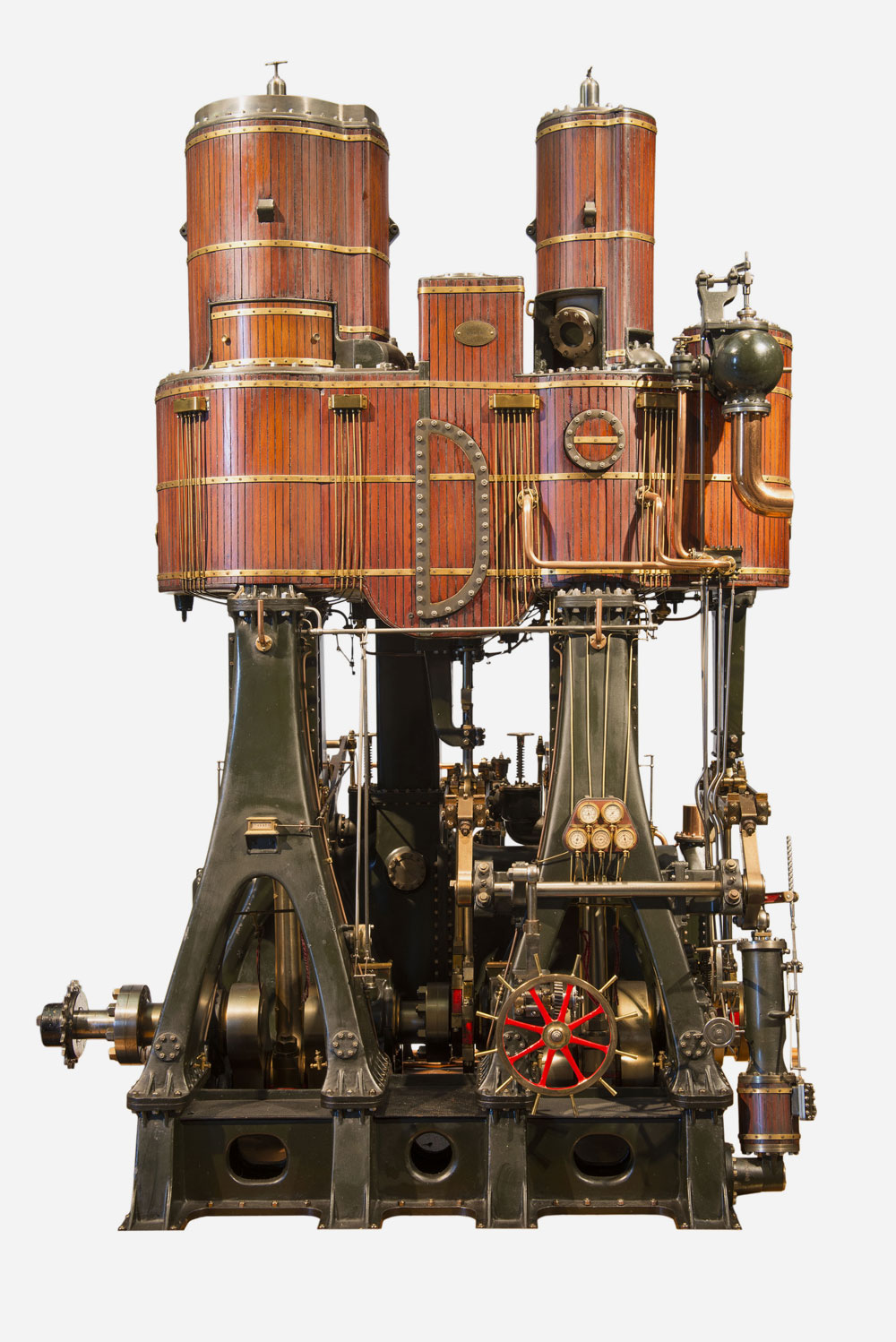

Model of a quadruple expansion tandem engine, designed by Walter Brock and made by David Carlaw, for William Denny Brothers, Dumbarton, Scotland, 1887. © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums

The V&A’s new show, curated by Ghislaine Wood and Daniel Finamore, tracks the origins of the transatlantic crossing from the early days of mail ships and mass immigration, when the cargo and the destination mattered far, far more than the cramped, uncomfortable journey. But as the moneyed, leisured upper classes started to spread their wings, the ocean liner came into its own, a grand hotel at sea offering glamorous social interaction and company, entertainment and dining of the very highest quality. Class mattered more at sea than on land, and different levels of social status were conveyed unambiguously through design.

Governments started to see their liner fleets as floating embassies for national identity and strength, and the Blue Riband – awarded to the fastest Atlantic crossing – changed hands several times in the 1920s and 30s. There were other factors at play; the big liners had an essential role in carrying troops and equipment during the war, so it made sense for governments to bankroll their construction in times of peace. The boats provided the capacity, but the shipping companies – Cunard, White Star, the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique, United States Lines and so on – provided the glitz, as liners evolved from the cluttered Edwardian splendour seen in White Star’s Titanic and Olympic to the sleek, populist modernity of the art deco era.

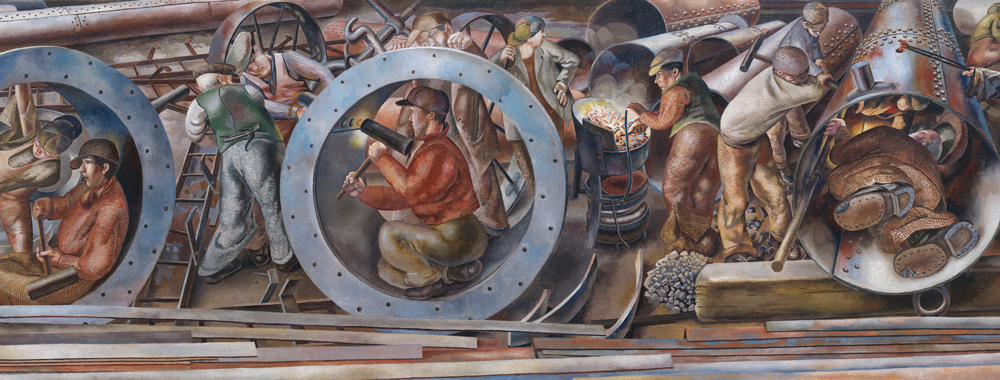

Detail of ‘Riveters’ from the series ‘Shipbuilding on the Clyde’, by Stanley Spencer, United Kingdom, 1941.

The exhibition emphasises the theatrical, from the room-sets containing reclaimed artwork and furniture to the large-scale recreation of a grand salon, all mannequins and mirrors and wall-to-wall projections of the Atlantic horizon. The ocean liner inspired some of the most evocative and beautiful posters ever printed, but the total design approach extended to all areas, from menu cards to the corporate architecture of their head offices. The most splendid era of all – the late 1920s and 30s – was of course curtailed by war, and the sheer scale of the waste is still staggering; the Normandie, perhaps the ultimate art deco object, only sailed for four years from 1935–39, before catching fire and sinking as it was being converted to a troop carrier.

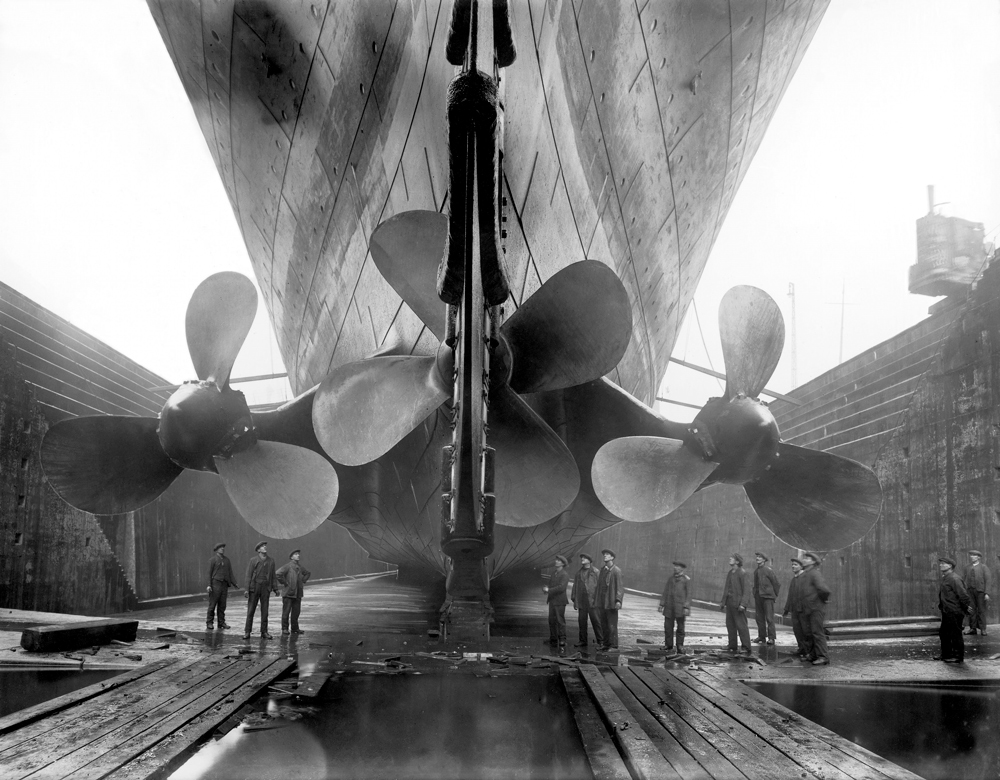

Titanic in dry dock, c.1911.

The post-war era was more populist, and the strict social stratification of the ocean liner started to become a little more relaxed. Names like Marion Dorn, Edward Ardizzone, the Cassons, Edward Bawden, Gio Ponti, David Hicks, Ernest Race, Robert Heritage and more, turned their hand to the interiors of the new-era liners, fighting an unwinnable war against commercial aviation. The exhibition captures these dying days of unassailable style, and the 250 objects take the visitor on an intriguing and bittersweet voyage, the extremes of which will probably never be seen again. Cruise ships are still a thing, of course (the exhibition is sponsored by culture specialist Viking Cruises), but the scale and drama of the big ocean liner remains a potent symbol of our vision of luxury travel.

Left, Paquebot ‘Paris’, by Charles Demuth, United States, 1921–22. © Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio. Right, Empress of Britain colour lithograph poster for Canadian Pacific Railways, by JR Tooby, Canada (possibly), 1920–31.

Silk georgette and glass beaded ‘Salambo’

dress, Jeanne Lanvin, Paris, 1925. Previously owned by Miss Emilie Grigsby. Donated by Lord Southborough.

Left, luggage previously belonging to the Duke of Windsor, Maison Goyard, 1940s. Right, children’s chair from the first class playroom on Normandie, by Marc Simon and Jacqueline Dutch, France, 1934. California

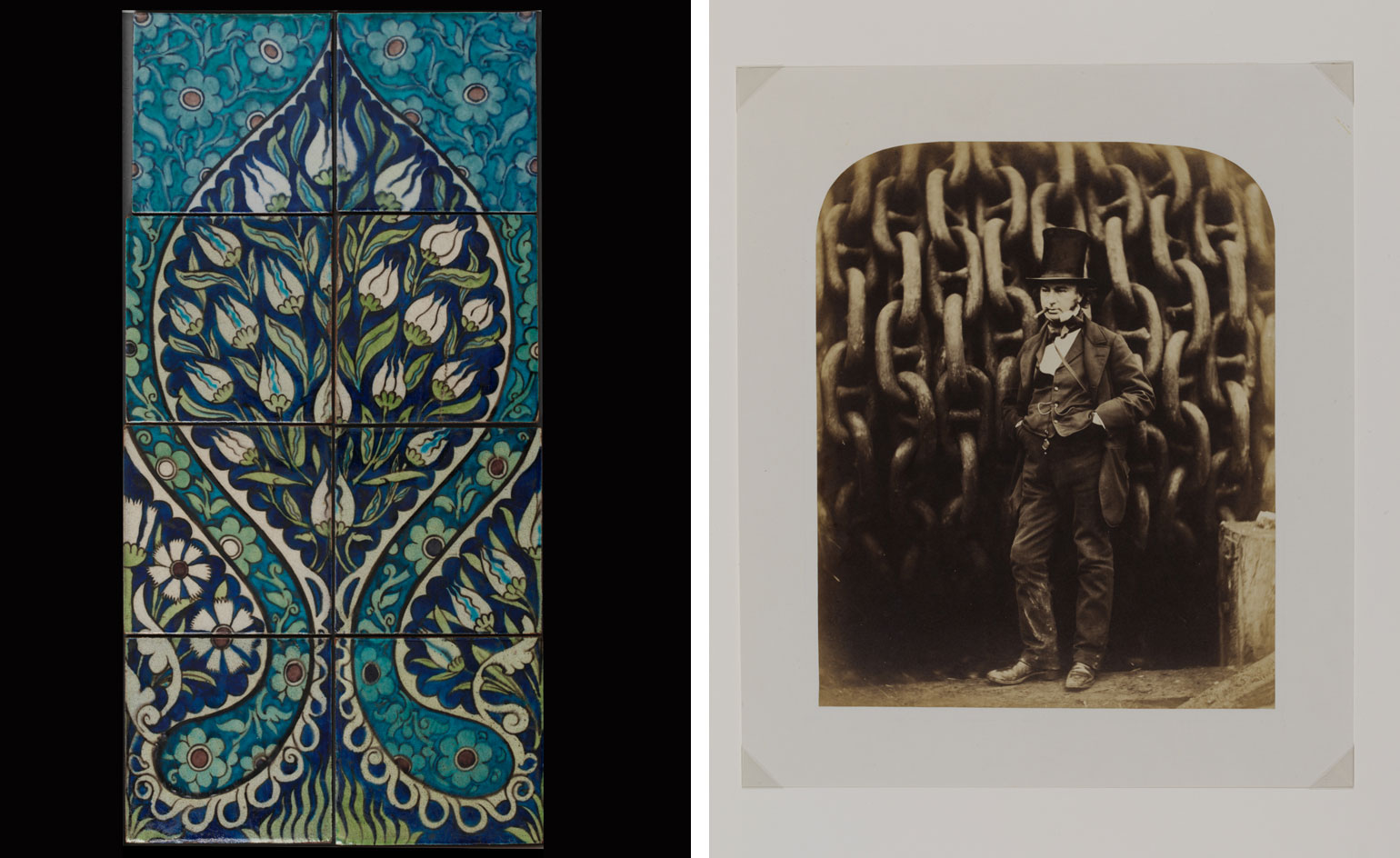

Left, painted earthenware tile panel for the saloon on Sutlej, by William de Morgan, United Kingdom, c.1882.© Victoria and Albert Museum. Right, Isambard Kingdom Brunel and the launching chains of the Great Eastern, by Robert Howlett, United Kingdom, 1857.

Panel from The Rape of Europa for the first-class grand salon on Normandie, by Jean Dupas, made for Jacques-Charles Champigneulle, France, 1934. California

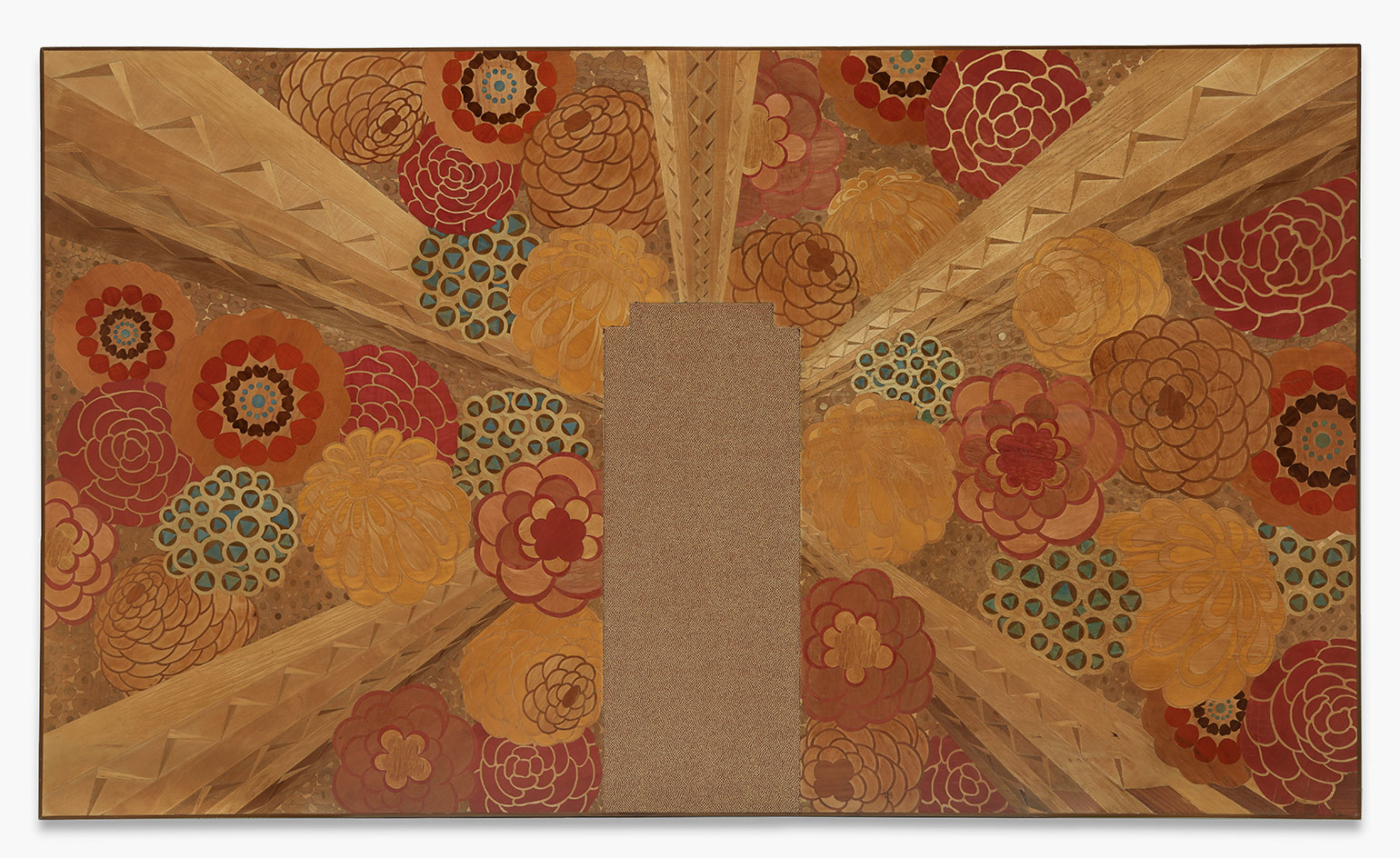

Wooden wall panel from the Beauvais deluxe suite on Île-de-France, by Marc Simon, France, 1927.

INFORMATION

‘Ocean Liners: Speed and Style’ is on view until 17 June. For more information, visit the V&A Museum website

ADDRESS

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Victoria & Albert Museum

Cromwell Road

London

SW7 2RL

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.

-

Japan in Milan! See the highlights of Japanese design at Milan Design Week 2025

Japan in Milan! See the highlights of Japanese design at Milan Design Week 2025At Milan Design Week 2025 Japanese craftsmanship was a front runner with an array of projects in the spotlight. Here are some of our highlights

By Danielle Demetriou

-

Tour the best contemporary tea houses around the world

Tour the best contemporary tea houses around the worldCelebrate the world’s most unique tea houses, from Melbourne to Stockholm, with a new book by Wallpaper’s Léa Teuscher

By Léa Teuscher

-

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuit

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuitElla Kruglyanskaya’s exhibition, ‘Shadows’ at Thomas Dane Gallery, is the first in a series of three this year, with openings in Basel and New York to follow

By Hannah Silver

-

EV start-up Halcyon transforms a classic 1970s Rolls-Royce into a smooth electric operator

EV start-up Halcyon transforms a classic 1970s Rolls-Royce into a smooth electric operatorThis 1978 Rolls-Royce Corniche is the first fruit of a new electric restomod company, the Surrey-based Halcyon

By Jonathan Bell

-

China’s Leapmotor pounces on the European car market with its T03 city car and C10 SUV

China’s Leapmotor pounces on the European car market with its T03 city car and C10 SUVLeapmotor’s tiny electric city car could be just the tonic for cramped urban Europe. We sample the T03 and its new sibling, the fully loaded C10 SUV, to see if the company’s value proposition stacks up

By Jonathan Bell

-

We make off with a MOKE and experience the cult EV on the sunny backroads of Surrey

We make off with a MOKE and experience the cult EV on the sunny backroads of SurreyMOKE is a cult car with a bright future. Wallpaper* sat down with the company's new CEO Nick English to discuss his future plans for this very British beach machine

By Jonathan Bell

-

Meet the Alvis continuation series – a storied name in British motoring history is back

Meet the Alvis continuation series – a storied name in British motoring history is backThe Alvis name is more than a century old yet you can still order a factory-fresh model from its impressive back catalogue, thanks to the survival of its unique archive

By Josh Sims

-

Hongqi’s Giles Taylor on the Chinese car maker's imminent arrival in the UK

Hongqi’s Giles Taylor on the Chinese car maker's imminent arrival in the UKHongqi makes China's state limousines. By 2026, it'll have a pair of premium EVs on UK roads. Giles Taylor, its VP of design, tells us about its design approach, and ambition in Europe

By Aysar Ghassan

-

British sports car builder Caterham teams up with the RAF to create this bespoke machine

British sports car builder Caterham teams up with the RAF to create this bespoke machineHelicopter parts are repurposed for the bodywork of this Caterham Seven 360R, built in collaboration with RAF Benson

By Jonathan Bell

-

LEVC’s L380 is a truly magnificent minivan

LEVC’s L380 is a truly magnificent minivanThe London Electric Vehicle Company’s L380, is a magnificent minivan designed for upscale long-distance travel, as the maker of the London Taxi branches out into all-purpose EVs

By Jonathan Bell

-

Will this UK company secure the future of classic cars?

Will this UK company secure the future of classic cars?Everrati, a specialist UK engineering firm hailing from the rolling hills of the Cotswolds in the UK, thinks it holds the key to classic car electrification

By Jonathan Bell