Algorithms of the heart: can our all-new Wallflower* app add to the online dating buzz?

At Wallflower* we understand that compatibility really counts, especially in the bedroom. But also the lounge. And wet room. Even in the home office. How many amorous stirrings have wilted on the vine at the sight of the wrong Wegner or sub-standard task lighting? Wallflower’s unique, design-focused digital card system and the powerful analytics of our carefully coded, AI-enhanced love-bots (not to mention the lustrous illustrations by Klaus Haapaniemi), bring together only those with perfectly attuned interior lives. No more indiscriminate data-dump or frenzied swiping. So come out of the virtual kitchen and mingle. Wallflower* is the perfect party in your pocket...

Finding sex, love or both used to require a degree of human endeavour; it required actually going out and meeting people. Then, if you made it to a first date and were British, you drank a lot of alcohol and had sex. If you were American, you asked each other a series of searching job-interview-style questions, including salary and frequency of gym visits, and then, conditions being satisfactory, delivered efficient oral sex. Neither system guaranteed a second date.

These quaint, analogue traditions that the greyer-haired Gen Xers can dimly remember are the habits of a century past. Digital dating has ensured that the joy and pain, humiliation and disappointment have endured, but the style of their delivery has changed with tech’s disruptive advance.

In 1996, about 77 million people worldwide had access to the web. It was a marginal interest. The only industries making any money out of this little virtual village were, firstly, dear old porn and, secondly, a newfangled thing called internet dating. Yahoo – a directory compiled by humans, not algorithms – listed 16 dating sites, of which just one, Match.com, survives to this day.

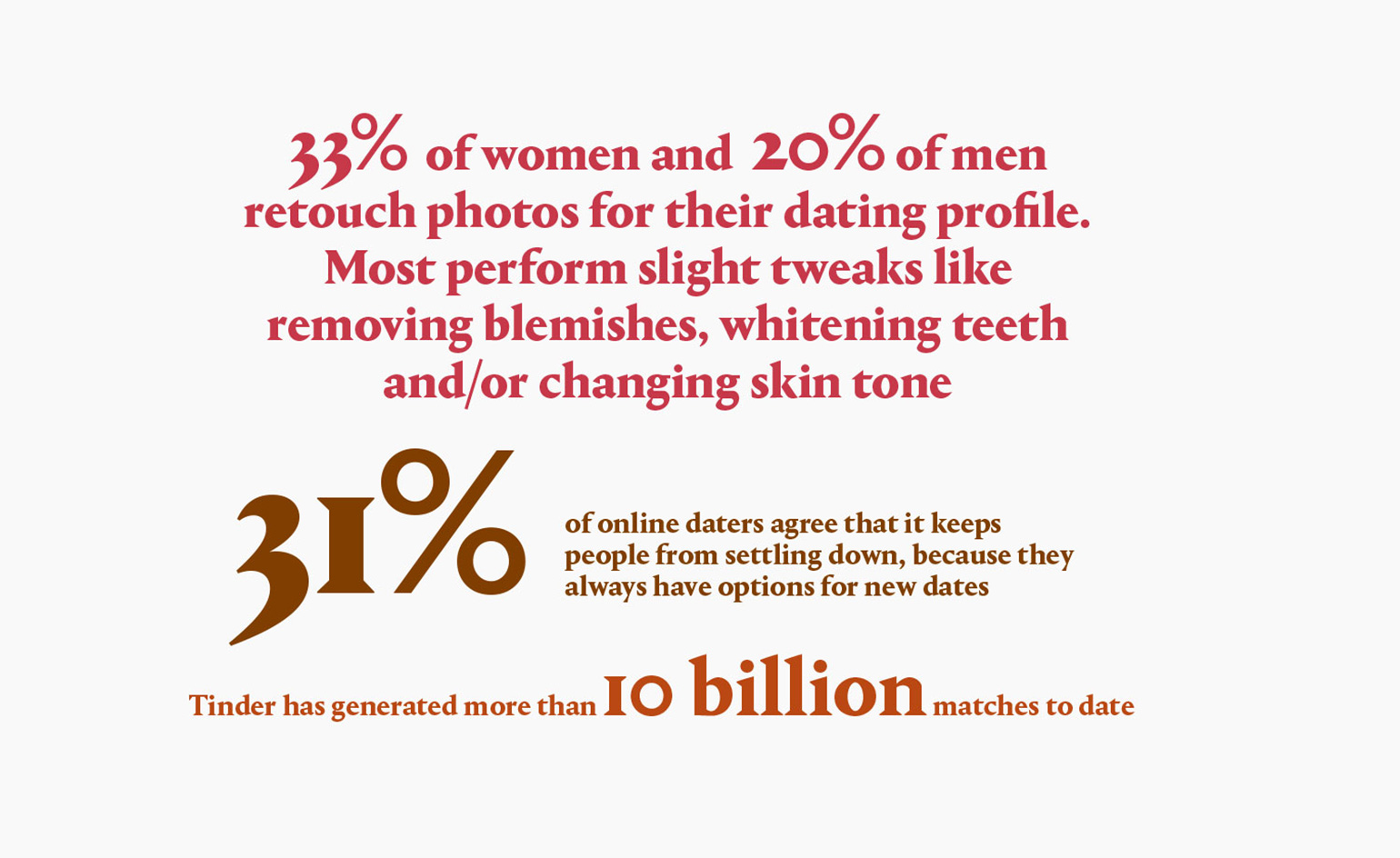

Sources: Hinge Pew Research Center, Global Web Index, Meitu, Tinder, Bloomberg, Plenty of Fish

‘Match will bring more love to the planet than anything since Jesus,’ said the site’s founder, Gary Kremen. Then, Match and the other dating websites were basically like the classified ads in the back of the paper. There were no smart algorithms designed to pair the compatible, there was just a bigger pool to pick from. ‘It was still very niche,’ says Rebecca Oatley, whose company, Cherish, worked on marketing some of those early sites in the UK. ‘Most people either had no idea what internet dating was, or they thought it was for geeks and losers who were light on social skills.’

The matchmaking machinery was pretty unsophisticated at this stage. You uploaded some words about yourself, often bordering on essay length, and sat back and waited for an email. ‘Tech just allowed you to place an ad,’ says Amarnath Thombre, chief strategy officer of the Match Group. ‘And search for people based on a few basic parameters.’

If you really had a grasp of this stuff, meeting people involved a rendezvous in a wine bar with an identifying item of clothing or a red rose in a lapel. And, as barely anyone had the technical savvy to upload a photo to the internet, there was the inevitable nail-biting wait to see if the date was a hottie or notty – and the nuisance of having to make polite conversation if they were the latter. ‘In the US there was a far greater acceptance,’ says Oatley. ‘But in the UK it really wasn’t anything you could admit to until the dot.com bubble made the internet a more acceptable place to be for professional people. They were tech-aware and working hard and had less time. It made sense.’

Of course, early adopters weren’t all socially inept geeks (a demographic, by the way, that has had a radical rebrand in the last 20 years, pretty much inheriting the earth and everything on it). A lot of people were secretly having a go. Hope, and curiosity, springs eternal – maybe the web could cast the net wide enough to find The One. Or, more accurately, maybe it could find sex.

Online dating was only half the story. With the big brand names, like Match, the mission was love. But sites like Nerve in New York offered a different kind of classified, advertising all kinds of casual and filthy sex: this was a prototype of ‘the hook-up’.

Unlike the hook-up, ‘The One’ is a sweet and nice idea, and this is what eHarmony promised to find – if you paid them money and answered 400 questions. Started by an evangelical Christian in 2000, ‘it was the first to dig deeper, with richer psychometric profiling and the promise of a special sauce – an algorithm that judged who was right or wrong for you’, says Thombre. It did well in the US but plateaued in the more secular UK, where the religious overtones smacked of patriarchal judgement.

‘At Match we did something similar, but we didn’t say there was a formula and we didn’t come with a religious agenda. We just used big data to look at what we could learn about people,’ Thombre adds. ‘Today, about five per cent of all American marriages are between people who met online.’

By the early Noughties, everyone knew Real Human Beings who had met other Normal People online. Guardian Soulmates didn’t have a ‘secret sauce’, but it brought together people who read the same newspaper. There was no way that Match and eHarmony, the frumpy juggernauts of internet dating, could satisfy the myriad tribes of humanity.

The fast-growing web community was no longer a village. Digital dating diversified. And it made people talk about it. JDate brought together Jewish singles, with profiles often written by their mothers. Christian Singles did the same. Farmers, dog lovers, herpes sufferers, fitness freaks – you name it, there was a dating site dedicated to it. Gold-digger looking for a sugar daddy? Go to Golddigger.com or Sugardaddy.com. ‘What people wanted was demographic, not psychographic assistance,’ says Thombre.

But let’s be honest, for Generation X it was a case of needs must. What was then called online dating was always an awkward and devastatingly uncool way to find some approximation of love. But 2004 was the year that online dating started to shed its loser reputation. Facebook launched, making friendship with near-complete strangers a constituent part of social networking’s casual-numbers game.

Do you remember your first poke? The Facebook poke facility was an irritating digital ‘Hiyaaaaa!’ most commonly used in a flirty ‘notice me’ way. The word poke is a vernacular term for sex: cue much tittering but less cringing. This more nuanced virtual scene on the social networks felt integrated with real life in a way that the dating sites had completely failed to do.

OK Cupid arrived on the scene in 2004, too. It used irreverent questionnaires that were an un-PC and entertaining way to see how compatible you were with others. (This year, the site was forced to take down a question that poked cruel fun at people with learning disabilities.) It was more like a game than a dating website, and it had tick boxes for things like recreational drug use and recreational bisexuality (heteroflexibility). OK Cupid was fast, kind of nasty and more about hook-up sex than eHarmony’s soft-focus hopes of marriage and love.

‘There was still a huge demographic that thought online dating was for losers. The way to attract these people was to make it free,’ says Thombre. ‘OK Cupid and Plenty of Fish were funded by irreverent ads; they used irreverent language. They helped remove the stigma and make online dating more cool.’

Of course, the seismic shift for online dating, as for much else, came with the arrival of the smartphone. Digital dating apps meant that, instead of trundling home after work and sitting sadly at your desktop, looking at awkwardly posed photos of ladies who may well be 100 miles away but shared your love of autumn walks and box sets of Friends, it was easy to upload pictures and to check in casually in the back of a taxi while you were going somewhere – metaphorically and literally. ‘That changed everything. That was the big disrupt,’ says Thombre.

With the smartphone came Grindr in 2009 (gay men were way ahead of the game, as always) and the digital cruising of the location-based dating app. Forget searching the same city. Who was available, say, in the same bookshop? Many imitators followed, including Jack’d and Scruff. But it took five years for the hetero version of Grindr to drop.

Do you remember your first swipe? That changed everything. See a face, dismiss it, over and over and over again. It was something to do with friends, a laugh. Between 2013 and 2016, the number of 18- to 24-year-olds using dating apps shot up from ten per cent to 27 per cent; that’ll be down to Tinder, which launched in 2014.

Today, Thombre’s Match Group owns some of the biggest names in digital dating including Tinder, and controls around 25 per cent of a market estimated to create $2bn in revenue in the US alone. Digital dating isn’t going away.

I speak to a 26-year-old who writes for a well-known super-cool website. She’s the digital native who doesn’t discern between IRL (in real life) and virtual. ‘I don’t even bother thinking about relationships in the way that I thought I would when I was in my teens,’ she says. ‘Why would you when there are always 4,000 others in my phone who might be better.’

Swipe, swipe, swipe. The speed with which we liked or didn’t like a human face was the speed at which dating apps go out of fashion. Look on Tinder now and there are copious faces but slim pickings in terms of quality. There are an estimated 8,000 dating apps worldwide. And, right now, all the hot guys are on Happn. No, Bumble. Or is it Facemate? Hinge? Revealr? Mesh? No no no, it’s all about League, of course.

League is for the college-educated. It’s strict on picture quality, so no fuzzy mugshot selfies taken by the urinals in the Gents. You have to bring your A game. It downloads your LinkedIn profile and everyone is vetted; it has a waiting list of 100,000, allegedly.

‘We’re not a dating app. We’re more like Soho House or [high-end gym chain] Equinox,’ says League’s community and operations manager, Meredith Davis. League members meet up, IRL, and human beings, not algorithms, check if you’re handsome and smart enough. ‘Dating online has become more like an awesome private members’ club with an awesome singles scene,’ Davis adds. ‘It used to be embarrassing, but now you have people proud to say, “I’m glad I swiped right.” There is nothing weird about it.’

But tell us there’s nothing weird about PokéDates – an app that lets people search for hook-ups or potential life partners while playing Pokémon GO – and we’ll tell you you’re weird, or a Millennial.

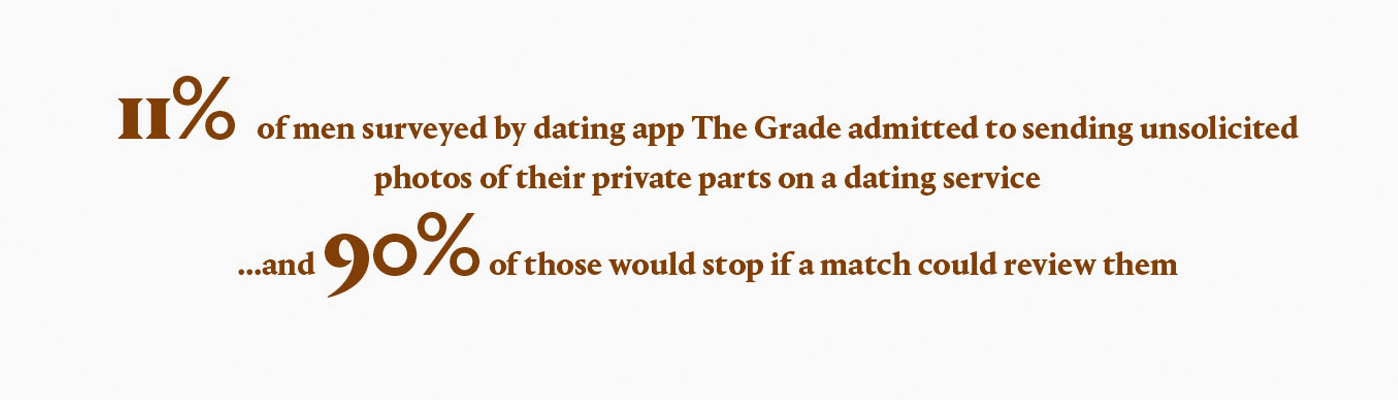

Source: The Grade

The problem with the virtual over the actual is choice overload, according to Sean Mahoney of culture forecaster Sparks and Honey. ‘For the younger Millennials and the Generation Z following them, AI [artificial intelligence] will help them parse this mess. We will have our own personalised bots who will chat to each other as an act of curation.’

The super-smart algorithms required of these bots will ‘act like an actual human matchmaker and be able to remove people’s unhealthy preferences, instead determining whether you are making the really right decisions for you’, Mahoney says.

So, there you have it: technology has managed to recreate the interfering old aunt in the village who arranged all the marriages back in medieval times. Despite all the dildonics and virtual-reality love-matching that lies ahead, what we really want is for someone else to sort it out. It’s back to the future, as usual.

As originally featured in the November 2016 issue of Wallpaper* (W*212)

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti