Norman Foster finds emotional soul of the automobile in Guggenheim Bilbao blockbuster

Norman Foster curates ‘Motion. Autos, Art, Architecture’ at the Guggenheim Bilbao, an epic exhibition linking the history of the automobile with the evolution of modern art

Assembled beneath the rippling titanium skin of the Guggenheim Bilbao is a new display of art objects. Only this time, the objects in question weren’t created as art, but design. ‘Motion. Autos, Art, Architecture’, curated by Norman Foster, is a far-reaching blockbuster show that traces the connection between the history of the automobile and the evolution of modern art, a winding road that takes in high and low culture and passes through a shifting cultural landscape.

The Sporting gallery, introduced by the 1955 Mercedes-Benz 300 SL ’Gullwing’, with Nick Mason’s 1962 Ferrari 250 GTO to the right

Foster (or Baron Foster of Thames Bank) is a longstanding and unabashed car enthusiast, whose interest spans practically all modes of transport. He is a keen driver and car collector, an accomplished pilot (of fixed-wing craft and helicopters), and a passionate fan of yacht, train, and aircraft design; and his architecture can be interpreted as a lifelong desire to splice the accelerated innovations of transportation design with the world of construction.

Although Foster’s buildings frequently cross-pollinate the disciplines – the Sainsbury Centre’s corrugated metal panels were inspired by the Citroen 2CV, for example – he still remains in thrall to the most wondrous examples of mobility design, many of which are on display in ‘Motion. Autos, Art, Architecture’.

Porsche 356 Pre-A, 1950, with the 1961 Jaguar E-Type to its left. At the rear is one of the 1964 Aston Martin DB5s used in Goldfinger

The architect once told The Guardian newspaper that ‘as a child I lived in a fantasy world inhabited by these cars and their legendary drivers: Bernd Rosemeyer in the rear-engined Auto Union and Rudolf Caracciola in the Mercedes-Benz, racing at Nürburgring, Tripoli and Monaco.’ ‘Motion. Autos, Art, Architecture’ is a golden opportunity – a highlight in a career that shows no signs of slowing down – to bring these passions together. It’s a topic that's almost too big to be condensed into galleries, even those as expansive as the ones Frank Gehry opened back in 1997.

Foster and his co-curators, Manuel Cirauqui and Lekha Hileman Waitoller, have carved nearly two centuries of history into seven themed rooms, Beginnings, Sculptures, Popularising, Sporting, Visionaries, Americana, and Future. In addition to the 38 cars, there are several hundred works of art, ranging from sculptures to photographs, Pop Art icons to esoteric ephemera.

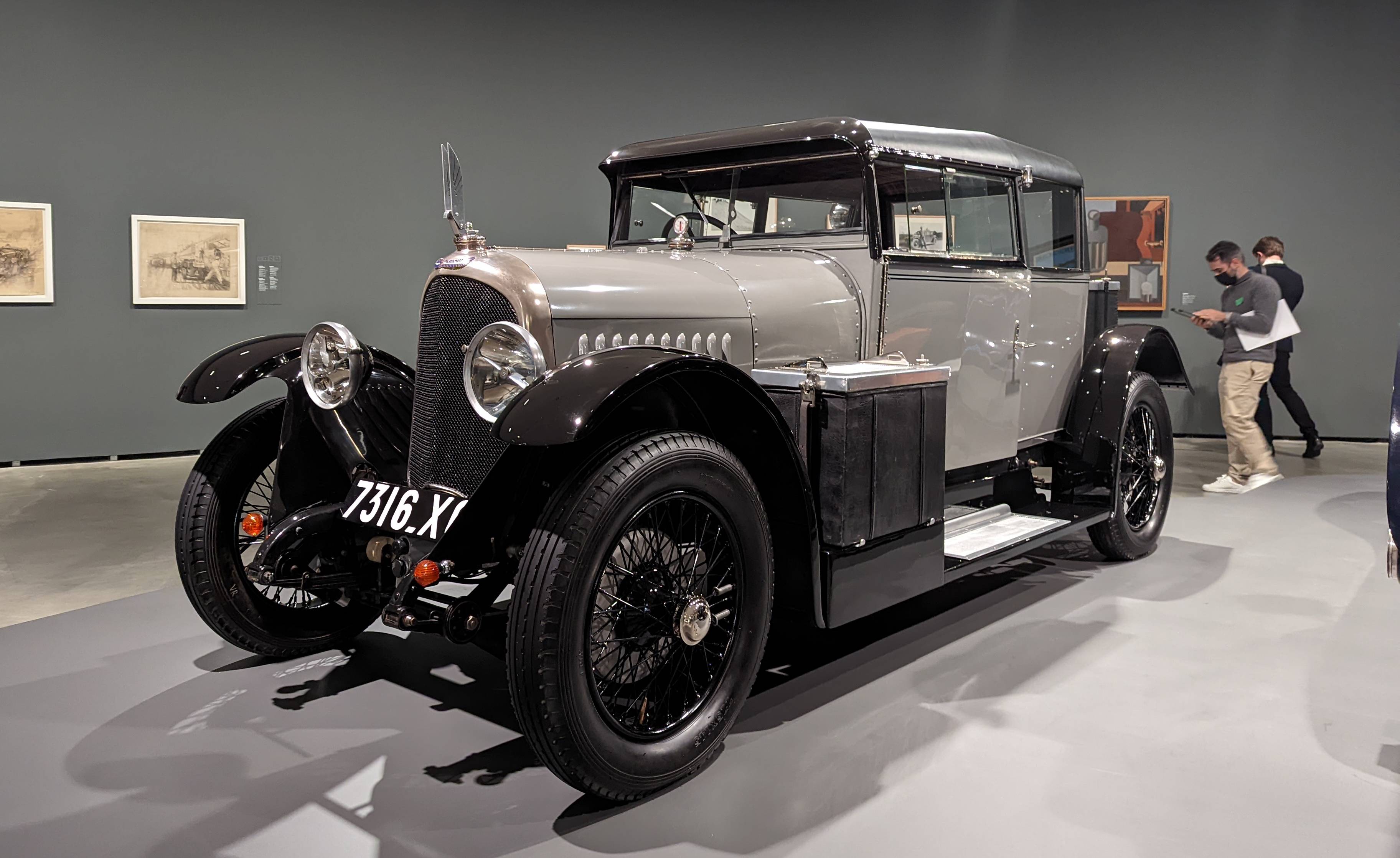

The Voisin C7 ’Lumineuse’, once driven by Le Corbusier

On the one hand, the show is a vindication of a narrative that has run through architecture and design since the early modern period: industrial art is art, period.

‘These are extraordinarily beautiful objects, and they coexist at an equal level with great works of art and architecture,’ Foster told the assembled press corps. ‘There's a cultural synergy and that is against the silo mentality where we think of something as fine art and these objects as just a kind of car.'

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

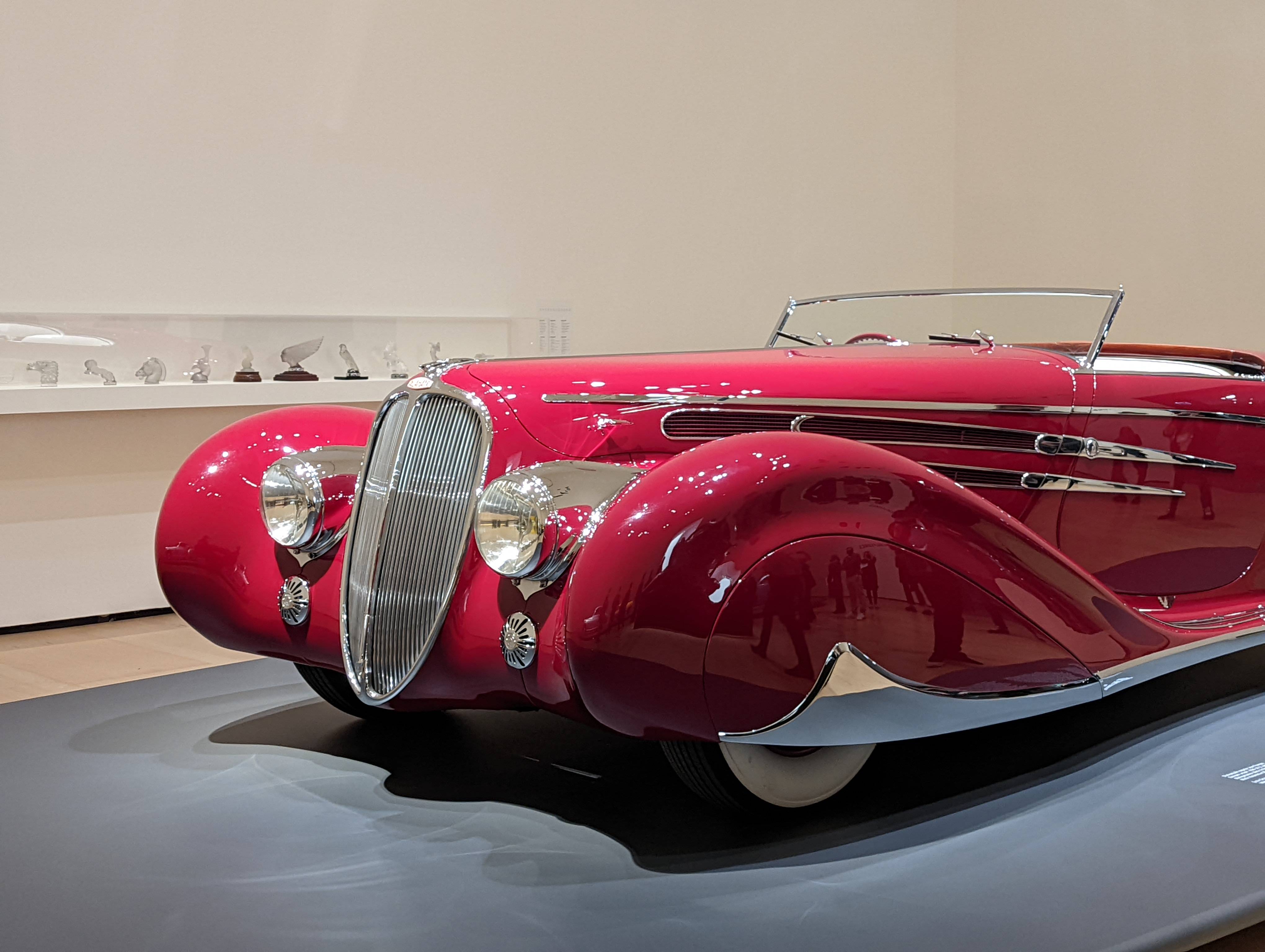

1938 Delahaye Type 165 Cabriolet, with bodywork by Figoni & Falaschi

The Sculptures room is perhaps the most honest representation of the automobile's current wayward status. Grouped around a Henry Moore, beneath a gently twisting Calder mobile, are four of the most astonishing car designs ever built, the Bugatti Type 57SC Atlantic of 1936, a Bentley R-Type Continental from 1953, the one-off 1938 Delahaye Type 165 Cabriolet, and the equally unique Pegaso Z-102 of 1952, concours-quality examples that evoke wonder in the most hard-hearted anti-car campaigner.

They are beautiful, but also not of this world, scarcely belonging to the eras they were born into, representing instead the tastes and desires of a bygone 1 per cent. The automobile is an art form, and like all art forms, it takes many shapes and crosses many boundaries. There are four-wheeled equivalents of Monet and Picasso, just as there are automotive Warhols and Banksys.

The sole surviving ’Cupola’ version of the Spanish 1952 Pegaso Z-102

These four beauties stand in stark contrast to the ‘people’s cars’ in the following room, Popularisation. Technology transformed mobility for the masses, but even these supposedly utilitarian icons have now been transformed once again into cult objects. For car makers, they are aesthetic springboards for modern products, new cars that generate their emotional heft by stirring up the past.

Of the cars on display here, four have been revised in recent memory, with Volkswagen’s electric ID. Buzz (heard but not seen in the show) the most recent example of the memory-bank smash and grab that defines so much of the modern car industry.

Half a Mini, a 1966 model that showcases the car’s ingenious packaging

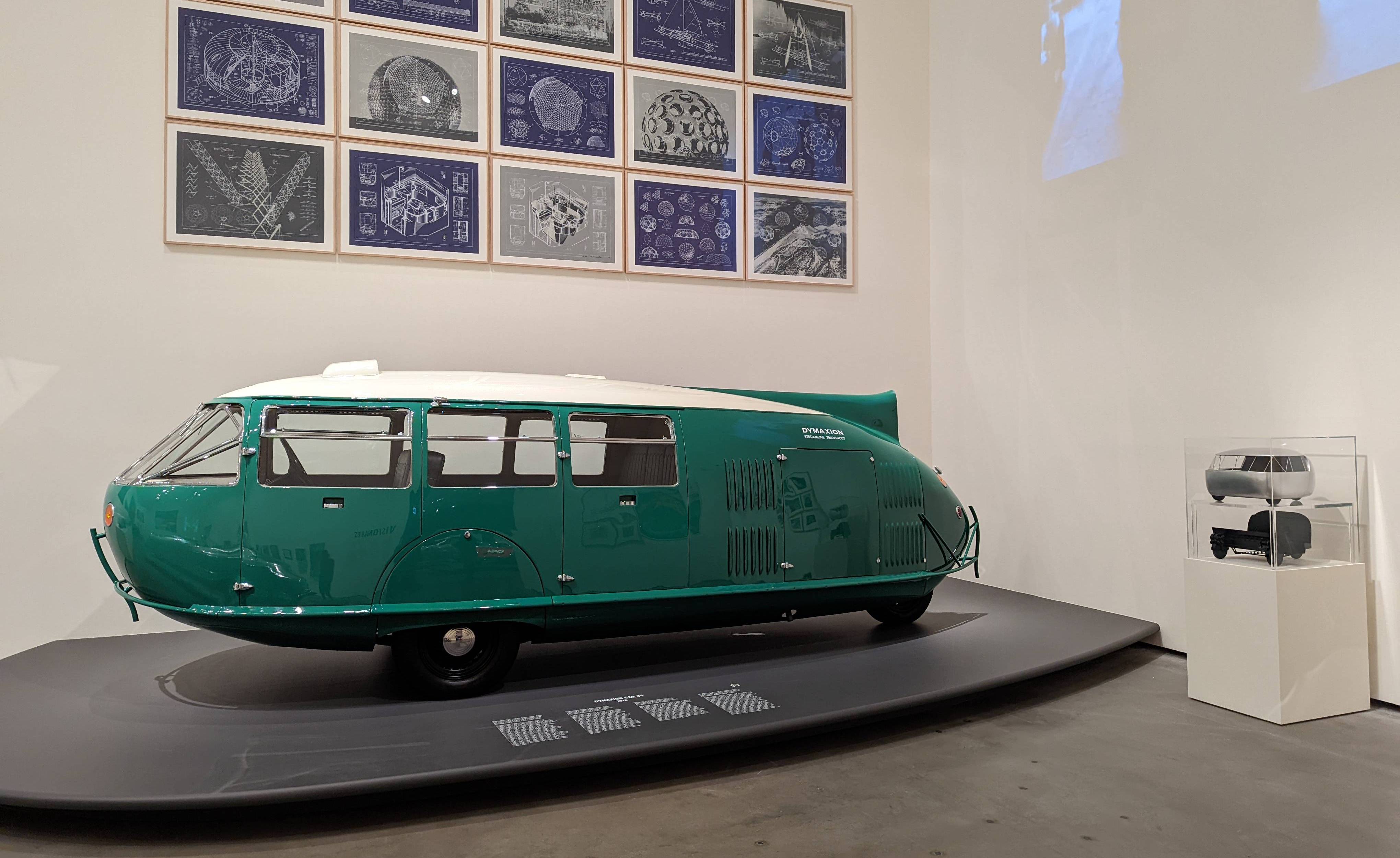

There are stand-out exhibits at every turn. A case in point is Foster’s own Dymaxion Car, a loving replica created for him by East Sussex specialist Crosthwaite & Gardiner, based on the sole surviving example of the three prototypes built by Buckminster Fuller in the 1930s. Finished in emerald green, with a cream roof, it sits beneath a galaxy of blueprints of Fuller’s pioneering architectural projects, an homage to the man who had been Foster’s tutor and mentor at Yale.

It's not the only car with a direct architectural connection in the show. In addition to the wooden recreation of Le Corbusier’s 1936 Voiture Minimum, on loan from London’s Design Museum, there’s also a stunning rarity from the Foster collection, Le Corbusier’s own Voisin C7 ‘Lumineuse’, a striking French saloon from 1925 that was frequently foregrounded in the period architectural photography of the Swiss master’s houses.

1951 Volkswagen Beetle, shown alongside just a few of its representations in art and pop culture

By our count, 11 of the vehicles on display came from the Foster Family Collection, a testament not only to the architect's long-standing interest in all forms of transportation design, but also to the investment potential of a well-burnished classic.

The Foster portfolio is extensive, but probably no match for Nick Mason's Ferrari 250 GTO, a car that would cost as much as a good-sized apartment building.

1970 Lancia Stratos Zero concept car, from the collection of Phillip Sarofim. Andreas Gursky’s epic pitstop portraits provide a fitting backdrop to Lewis Hamilton’s 2020 Mercedes F1 car

It's the logistics attached to such values that made this exhibition the most complex project in the Guggenheim’s quarter century. Foster’s impressive curatorial clout must have helped, leaving other recent shows, notably the V&A's ambitious ‘Cars: Accelerating the Modern World’, looking rather anaemic in comparison.

Being able to rope in some of the world’s most significant collectors and museums and persuade them to ship their precious cargo to Bilbao for five months is not a given in today’s unstable world. Yes, many of these machines are the clichés of car history, rightfully celebrated for their beauty and innovation, but clichés nonetheless. Yet it would be exceptionally churlish to whinge about such a glorious – and probably unrepeatable – opportunity to see so much iconic precious metal gathered together in the same place.

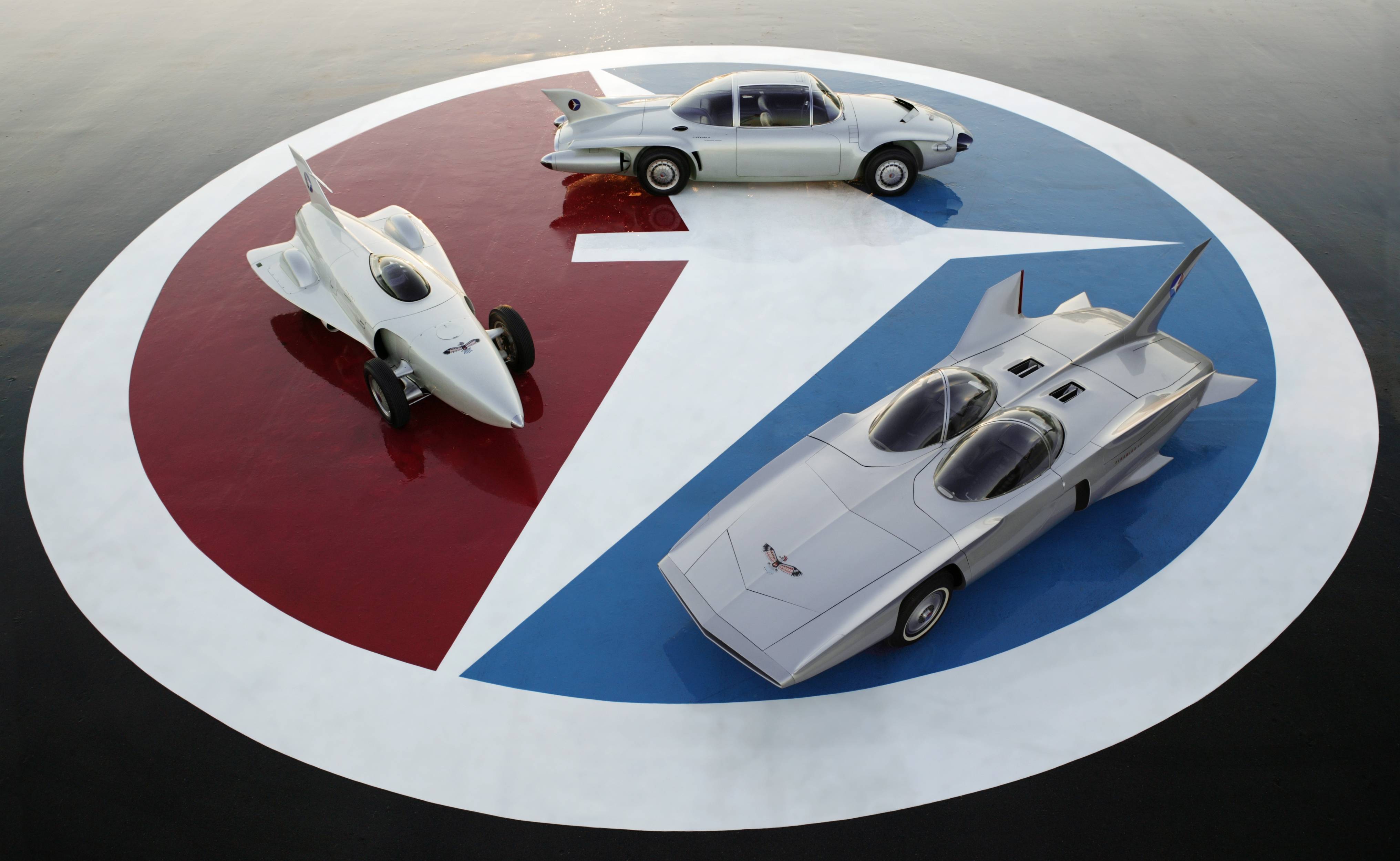

An archive image of Firebirds I, II and III, built between 1954 and 1958 by General Motors

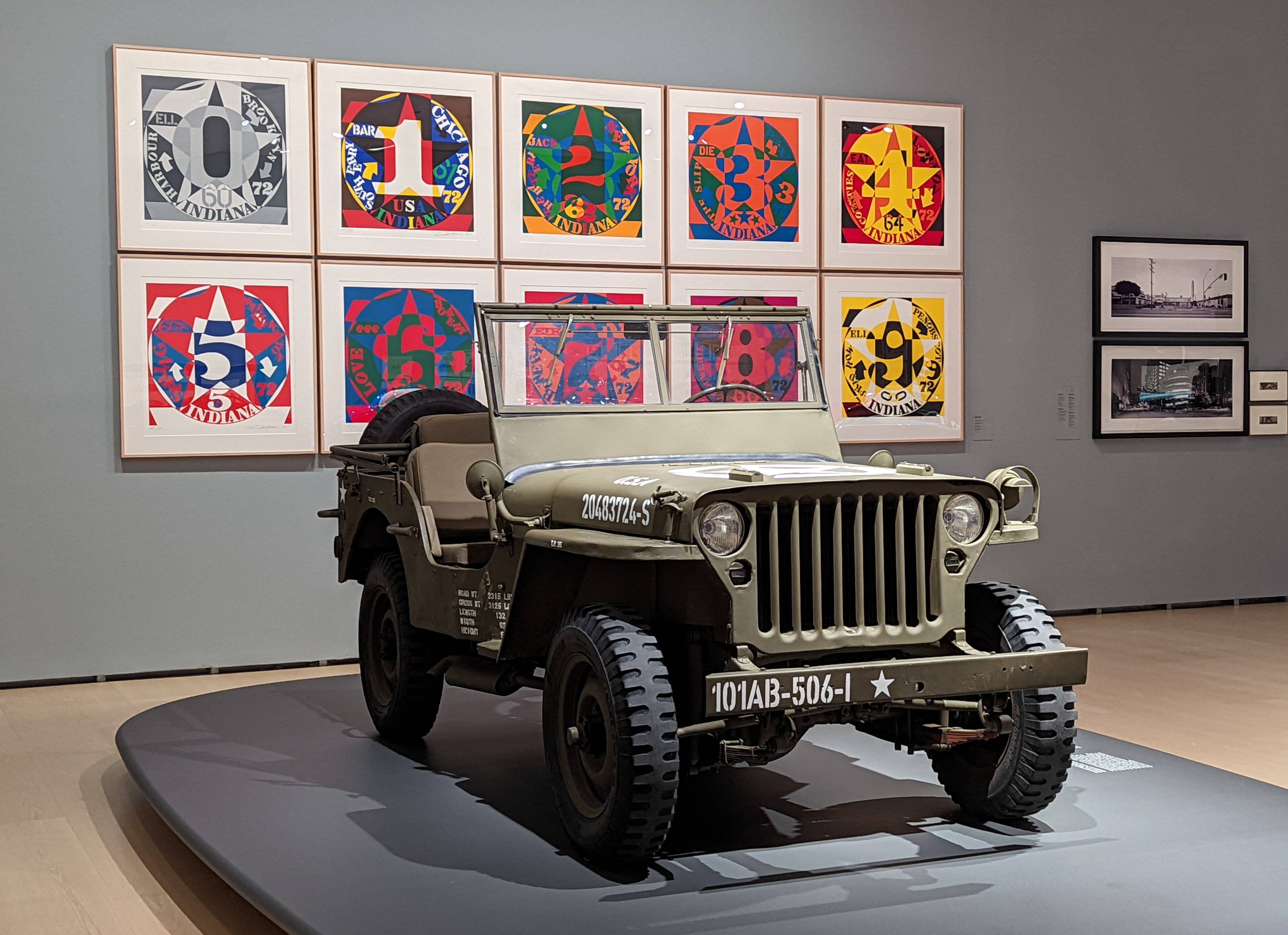

The curation goes big on juxtapositions, and it’s undeniably fun setting the wacky 1954 Alfa Romeo BAT 7 aerodynamic testbed against a backdrop of Giacomo Balla’s wild, swirling abstractions. The Firebirds sit beneath James Rosenquist’s 1970 painting Flamingo Capsule, a giddy homage to the Space Race, and 1950s photographs of the precise, modernist rigour of the General Motors campus. An original Willys Jeep from 1945, part of the Americana display, is set alongside Robert Indiana’s Decade: Autoportrait series, while Andreas Gursky’s epic photographic quartet, F1 Boxenstopp, is hung above Lewis Hamilton’s 2000 Mercedes F1 car.

Stars and stripes: the Willys MB ’Jeep’, 1945, and Robert Indiana’s Decade: Autoportrait series

The exhibition concludes with a selection of student projects from 15 design colleges around the world, institutions that have only recently dropped 'automotive' from their course names and replaced it with 'mobility'. The projects are a predictable combination of darkly dystopian, impossibly utopian, and wildly impractical, but all offer up a range of visions conspicuously absent from the mainstream conversation.

The wild retrofuturism of GM's Firebirds is sadly missed. Whether autonomy ever reaches sufficient sentience to safely guide us around the cities of tomorrow is still not a given.

Conceptual single person vehicle, designed by students at the University of Cape Town, South Africa

Foster seems undiminished in his enthusiasm for technology's ability to solve problems, even if some of these problems were manifestly created by technology in the first place. Unsurprisingly, he believes the car will always have a place in the city, regardless of what form it takes in the future.

'Will it be a mobile living room/bedroom? Will we all be transported nose to tail? Will insurance be an industry of the past because it's totally risk-free, or does it become more vulnerable to a cyberattack? I think it raises very interesting prospects. But there's always an optimistic scenario, I passionately believe that. The future is always better. So I think that we're on the edge of something truly exciting and positive.'

The future looks bright: archive image of GM’s Technical Center in the 1950s

There is an undeniable beauty in extreme engineering, a beauty that’s all the more apparent if you’re au fait with the complexities of manufacturing and mechanisms, of aerodynamics, powertrain and packaging. Car designers will tell you proudly that their discipline is far more of a mother of the arts than architecture, for not only do their creations have to seat people in cooled and heated, weather-shielded comfort, but they must do so at 70 miles an hour for hours on end, while producing strictly regulated emissions and saving the lives of all inside if they should have an accident.

Nevertheless, many architects persist in thinking they can try their hand at designing a car, which is perhaps why car culture was embraced so enthusiastically by the early modernist architects and city planners.

Turned up to the max: 1965 Ford Mustang and 1959 Cadillac Eldorado Biarritz

That enthusiasm is waning. One of the big – and inevitable – omissions was the emergence of truly critical art. The automobile’s two-way street of influence with art, design, architecture, and culture hasn’t always been so hagiographic and the exhibition celebrates the euphoria generated by the car, rather than its flipside. Throughout their history, cars have been put on pedestals by artists, enthralled by the thrilling modernity of speed and sound. These works are very well represented, but perhaps the loudest dissenting voice is John Chamberlain’s 1962 sculpture Dolores James, a scrap metal concoction that hints at the shocking violence wrought by the car since its invention.

There’s no Ballard or Banham, no awkward questions from the likes of Iain Sinclair or Heathcote Williams, no Warhol car crash silk screens or Chris Burden-style auto-erotic S&M. In fact, there are no art cars at all, save for a set of maquettes from BMW’s long-running cultural outreach programme. Perhaps this is a different kind of perversity, the thrill of enjoying the soon to be outlawed, a daring flash of exhaust pipe, the terrifying roar of an F1 engine at full pelt.

John Chamberlain’s 1962 sculpture Dolores James

Foster acknowledges that ‘Motion. Autos, Art, Architecture’ is something of a final flourish for traditional car culture. ‘In some respects, [the exhibition is] almost a requiem for the age of combustion,’ he says. ‘What lessons do we learn from the past?'

For now, automotive futurism remains as inseparable from consumer desire as it ever was; futurism stimulates consumption. GM's Firebirds envisaged a future so bright that shades were obligatory, with the highways of tomorrow running fast and free, full of four-wheeled jet planes. The 1959 Cadillac Eldorado Biarritz was bigger and bolder than anything anywhere else, the American dream shaped in metal. This exhibition is struck through with a strong vein of nostalgia, as well as a certain sadness for chances missed, objects lost, and past times imperfectly remembered. As you might expect from a show sponsored in part by Volkswagen, it is not exactly bristling with critical barbs.

‘Motion. Autos, Art, Architecture’ includes a vitrine of toy cars through the ages

The narrative is tightly controlled, and even slightly revisionist at times, particularly with an origin story that portrays the automobile as a purifying agent of positive change, swooping to cities clogged and reeking with manure and horse carcasses. There's also a suspiciously convenient emphasis placed on the work of German-Jewish engineer Josef Ganz, whose ideas for a rear-drive small car, culminating in his Standard Superior of 1933, are seen by some as the true origins of the Volkswagen Beetle. Ganz was a pioneer who died in obscurity, but his recently revived and still unconfirmed story shows that origin stories and heritage will continue to matter to the consumer of tomorrow.

‘Motion. Autos, Art, Architecture’ is a veritable spaghetti junction of pathways, digressions, and connections. For the enthusiast, it’s unmissable. For the cynic and sceptic who might be wary of the car’s excellent PR representation, the exhibition goes some way to explaining why the automobile was and is a truly emotional subject.

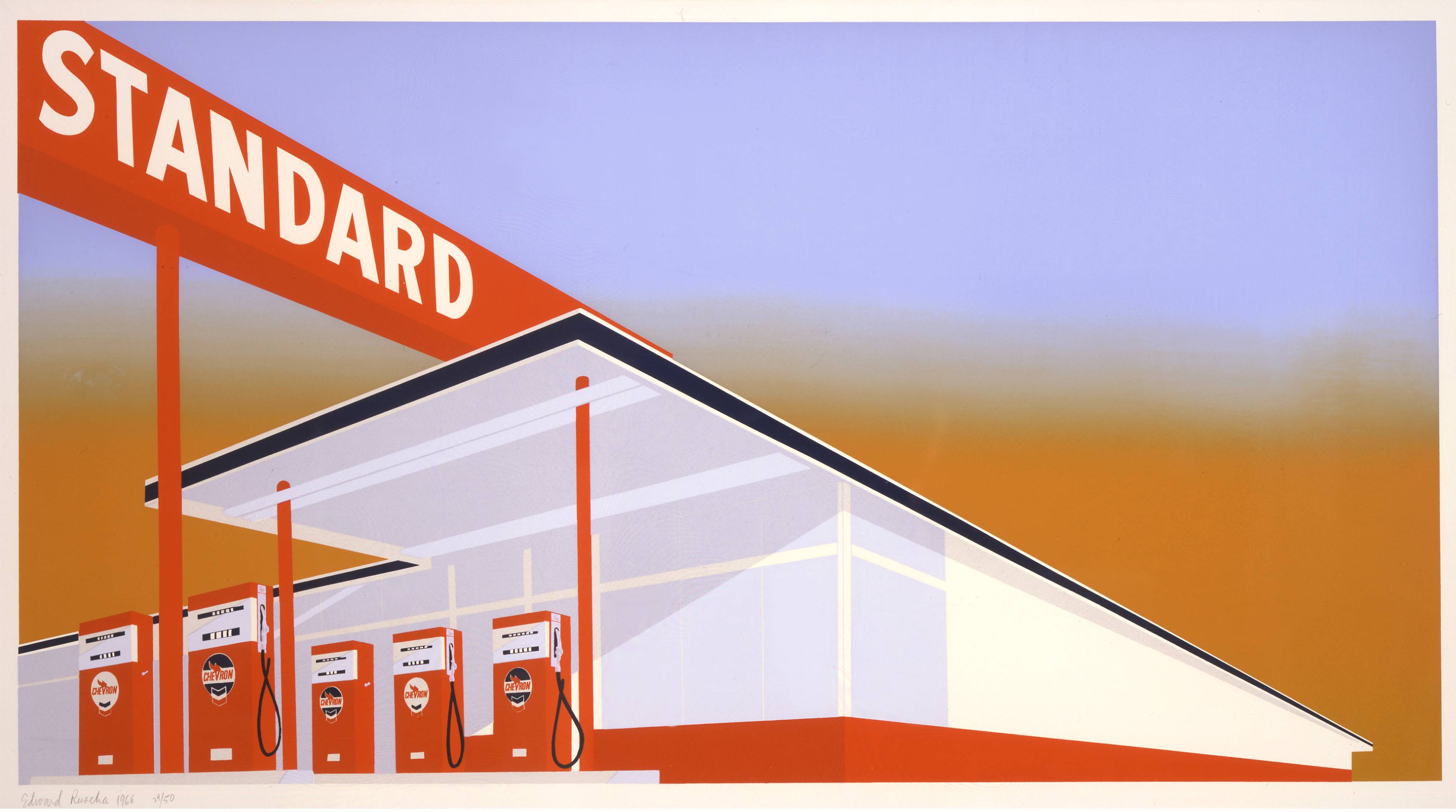

The end of the line? Edward Ruscha, Standard Station, 1966

INFORMATION

‘Motion. Autos, Art, Architecture’ is at Guggenheim Museum Bilbao until 18 September 2022

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.

-

Holland & Holland's Range Rover is outstanding in its field: shoot the breeze in style

Holland & Holland's Range Rover is outstanding in its field: shoot the breeze in styleCan you spare half a million pounds for a glorified four-wheeled gun cabinet? If so, the Range Rover Holland & Holland Edition by Overfinch might be the perfect fit

-

Veronica Ditting’s collection of tiny tomes is a big draw at London's Tenderbooks

Veronica Ditting’s collection of tiny tomes is a big draw at London's TenderbooksAt London bookshop Tenderbooks, 'Small Print' is an exhibition by creative director Veronica Ditting that explores and celebrates the appeal of books that fit in the palm of your hand

-

How Beirut's emerging designers tell a story of resilience in creativity

How Beirut's emerging designers tell a story of resilience in creativityThe second in our Design Cities series, Beirut is a model of resourcefulness and adaptability: we look at how the layered history of the city is reflected in its designers' output