Isolation to innovation: Inside Albania’s (figurative and literal) rise

Albania has undergone a remarkable transformation from global pariah to European darling, with tourists pouring in to enjoy its cheap sun. The country’s glow-up also includes a new look, as a who’s who of international architects mould it into a future-facing, ‘verticalising’ nation

By the time communism fell in Albania 1992, it was one of the poorest and most isolated countries in Europe. It had been presided over by dictator Enver Hoxha (and then his protégé Ramiz Alia) since 1944, during which time few people were allowed in or out of the country. Every aspect of life was controlled, from religion to property and trade, leading Albania to be dubbed by some ‘the North Korea of Europe’.

Standing on the beaches of Albania’s south, which attracts throngs of tourists during summer, it’s hard to imagine that boats from nearby Corfu once had to keep their distance for fear of being shot at. Albania had a chaotic transition to capitalism but, as the dust began to settle, and especially when it obtained Nato membership in 2009, the country began to come out of its shell. Albania has a new face now: ‘the Maldives of Europe’.

This is in reference to those southerly districts – the likes of Sarandë and Ksamil – where the water is as crystalline as any Indian Ocean archipelago. But those in the know (and as someone who is married to an Albanian and has been there numerous times, I humbly submit myself as one of those people) understand that that’s only the beginning.

In the north of the country, you can hike, kayak or even ski through the virgin territory of the Albanian Alps (which command the fantastically Tolkien soubriquet, The Accursed Mountains). The Valbona Pass is almost absurdly beautiful, yielding few signs of civilisation save the odd kulla (farmhouse), some of which are centuries old. Albania is also home to one of the last ‘wild’ rivers – more or less untouched by humans – in Europe, the Vjosa.

History abounds in the cities of Krujë – stronghold of the Albanian hero, Gjergj Kastrioti, commonly known as Skanderbeg, who led a rebellion against the Ottoman Empire in the 15th century – and Berat, a Unesco World Heritage Site dubbed ‘the city of a thousand windows’. As for the capital, Tirana? Perhaps lacking in some of the beauty of rural Albania, but without doubt a city on the turn, with the opening of high-end restaurants such as Mullixhiu, the rise of trendy neighbourhoods like Blloku, and a wave of futuristic-sounding architecture projects in the pipeline.

Albania’s changing horizon

A suite of radical high-rises helmed by high-profile architects are currently proposed or under construction in Tirana and beyond. ‘A wave of international architects is contributing to a cityscape that embraces multiple styles, creating a dynamic and pluralistic urban identity,’ says Lukas Rungger, founder of Italian firm Network of Architecture (NOA). ‘Albania’s architectural evolution is fast, vertical and diverse, making it a unique and fascinating case.’

The Skanderbeg Building in Tirana by MVRDV

Downtown One Tirana by MVRDV

NOA and local firm Atelier 4 are collaborating on Puzzle Tirana, which will resemble a stack of house-shaped ‘puzzle pieces’. Elsewhere in Tirana, Dutch architect MVRDV (whose past projects incude the Portlantis visitor centre and Depot Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam) is working on the Skanderbeg Building, a tower that is meant to resemble the profile of the eponymous hero, and Downtown One Tirana, which, at 150m, will be the city’s tallest building, with a ‘pixelated’ façade intended to look like a map of Albania. MVRDV was also the architect behind the renovation of the Pyramid of Tirana, originally built as a museum dedicated to Hoxha and now a major tourist attraction. ‘Albania has the potential to avoid the monotony that defines so many contemporary urban environments,’ says MVRDV co-founder, Winy Maas. ‘By embracing diversity rather than homogenising, it is cultivating a distinct identity.’

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

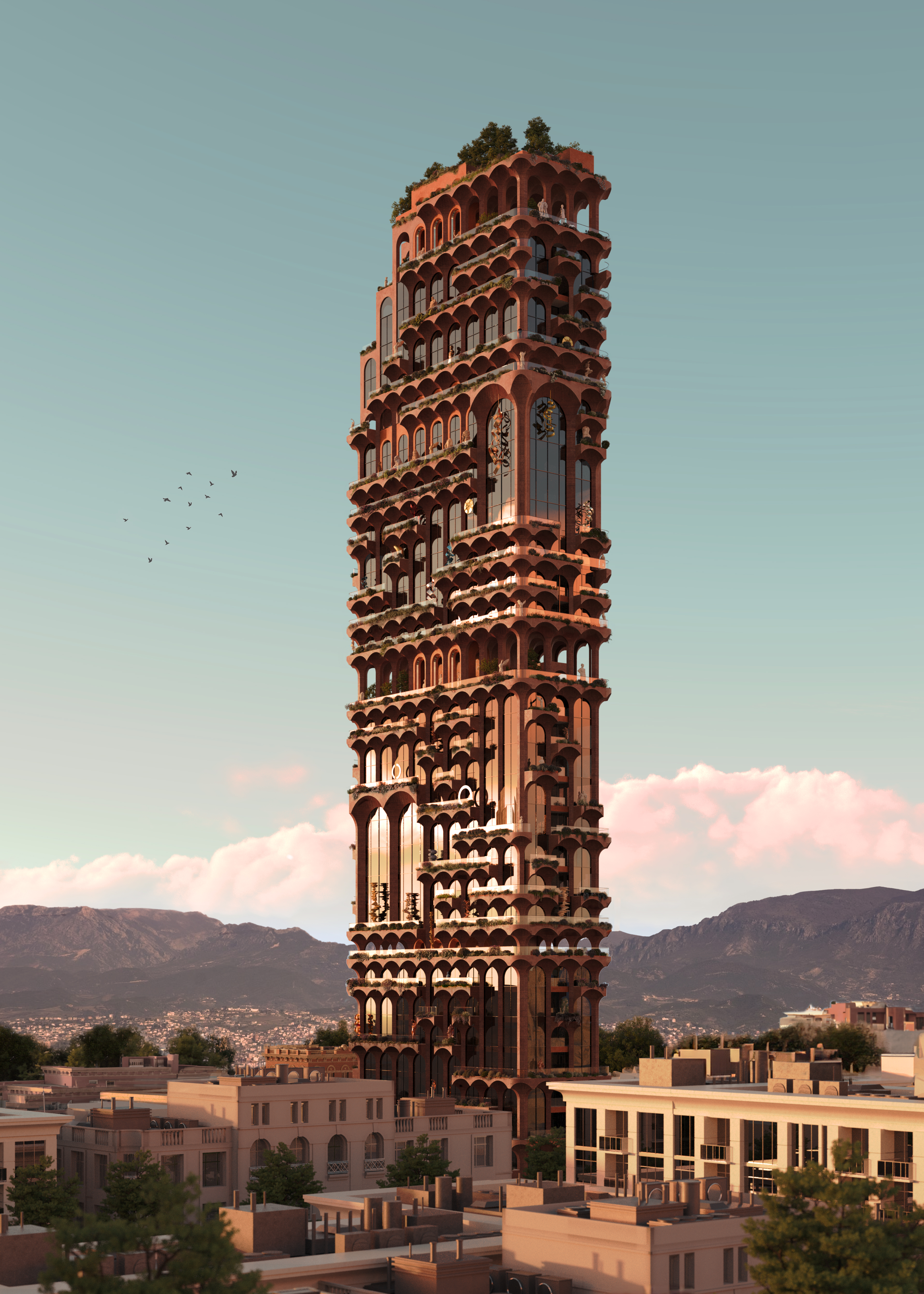

Downtown One Tirana’s claim to being the city’s tallest building will be short-lived on the completion of Rruga Adem Jashari by Swiss studio Valerio Olgiati, which is planning three towers designed to look like ‘totemic figures’, measuring 150m, 192m and 266m. New Boulevard by Czech firm Chybik + Kristof will be made from red concrete and take on a cascading shape that narrows as it rises, and Tirana Vertical Forest by Italian firm Stefano Boeri Architetti (known for similar ‘vertical forests’ in China and Milan) will be covered in 3,200 shrubs and 145 trees. Portuguese studio OODA has unveiled designs for Bond Tower, a pair of kinked skyscrapers inspired by a ballet dancer’s plié, and Hora Vertikale, which will be made up of 13 staggered cubic volumes.

Outside Tirana, mainly along Albania’s coveted coasts, the story is the same. The Red Sol Resort, planned by Spanish firm Bofill Taller de Arquitectura in Dhërmi, is immediately eye-catching for its blood-red palette. Italian studio Luca Dini is working on five new projects on the Albanian Riviera, including the medieval-inspired Colosseum 339. ‘Albania is undergoing a remarkable transformation,’ says Luca Dini’s head of architecture, Giovanni Ferrara. ‘It is increasingly positioning itself as a destination for cutting-edge architecture, and the new wave of projects showcases a bold vision for the future.’

The Pyramid of Tirana

These projects run alongside Tirana 2030, the masterplan set out by prime minister Edi Rama and the mayor of Tirana, Erion Veliaj, in 2017. The government is working with Stefano Boeri Architetti to realise this vision, which will triple Tirana’s green spaces, with the installation of new parks and nature reserves and the planting of two million trees. Public transport will be improved, a congestion charge implemented, and bus networks expanded. The city will also open the Park of the World, a square of international embassies, reinforcing Albania’s growing visibility on the world stage.

‘It is increasingly rare to find an influential architect who is not involved in Albania,’ says Diogo Brito, an architect at OODA. ‘Part of the reason for this is that there are fewer bureaucratic restrictions here – this unique condition provides architects with greater freedom to express their concepts.’

Rama’s preference for offbeat architecture can perhaps be explained by his background: the prime minister is a former artist, and spearheaded a public initiative to paint Tirana’s communist-era structures in bright colours. It’s an apt metaphor for the ‘out of the ashes’ moment that Albania has been enjoying for the last 15 years. ‘As the government continues to use architecture as a tool for socio-economic and cultural development, the next decade represents an unprecedented period for Albania,’ says Brito.

Bond Tower by OODA

Although the projects described above seem defined by their uniqueness, there is a common thread: each is specific to its context. This could be as obvious as Downtown One Tirana’s replication of a map of Albania – ‘a bold abstraction of national identity’, says Maas – or the Skanderbeg Tower, which ‘[turns] his portrait into an urban landmark’. Hora Vertikale, says Brito, ‘intends to make an interpretation of the chaotic nature of Tirana’, with the two towers serving as a ‘welcoming gate’. Puzzle Tirana, says Rungger, is a ‘deliberate reflection on the evolving identity of [Tirana’s] urban living’: ‘In the city centre, two-storey homes stand side by side with high-rise towers. This coexistence of scales inspired us to explore the encounter (or clash) between rural and urban life.’ Luca Dini’s Colosseum 339, meanwhile, features round arches that draw from historical Albanian fortifications.

‘The country is embracing contemporary design while preserving its rich cultural heritage,’ says Ferrara. ‘Buildings are not only aesthetically striking but also functional, sustainable and deeply connected to their surroundings. Our goal is always to elevate the built environment with a deep respect for place and culture.’

Hora Vertikale by OODA

Colosseum 339 by Luca Dini

Arian Galdini is the chairman of political party the Rinisje Movement and the author of the civic doctrine, Neo-Albanianism; he questions whether the preservation of national identity is quite as simple as creating a building that looks like Albania. ‘Our cities are undergoing a verticalisation that speaks to economic ambition, but too rarely to cultural intention,’ he says. ‘While projects like Puzzle Tirana or Downtown One have symbolic value, much of our construction remains speculative, unregulated and disconnected from human scale. The disappearance of vernacular forms and the privatisation of public space are troubling – architecture needs to serve a social purpose, where every intervention adds meaning rather than mass. The future will not be built by towers alone.’

Professor Gjergj Sinani – philosopher, intellectual, and the rector of University College Bedër in Tirana – agrees: ‘There is a visible attempt at aesthetic boldness, yet architecture is not just about building, but the ethics of space. The task is not to emulate the West blindly, but to cultivate a model of development that honours our past and engages our present.’

As Albania is moulded into a future-facing nation, its infrastructure must grow to support this. The opening of a second airport in Vlorë in 2025, which will handle up to two million passengers annually, will unlock Albania’s south. Various new railways and highways will further ease passage around the country, and Sarandë will see the expansion of its marina to accommodate more yachts. ‘These arteries of movement have altered not only our physical topography but also our psychological one, transforming isolation into aspiration,’ says Galdini. But his concerns about development as a ‘spectacle instead of a strategy’ persist.

A world nation

In 2024, 11.7 million tourists visited Albania – up 15.2 per cent on the previous year, according to the Albanian Times. In 2023, the country ranked fourth globally for the largest percentage increase in international arrivals, according to the UN Environment Programme (UNEP).

Rama forecasts that the country will welcome 20 million tourists in 2030, enough to rival its neighbour Croatia. In March 2025, he addressed attendees of the travel and tourism fair, ITB Berlin, saying, ‘Albania has developed from a hidden gem to a tourist powerhouse in only a short space of time’, pointing out how, along with Saudi Arabia and Qatar, Albania led the rankings in tourism growth, ‘even without a FIFA World Cup or Mecca’.

There is a fine line between ‘buzziness’ and overtourism. Just look at Venice, Bali or Santorini, places that have encountered environmental damage, infrastructure strain and social tensions due to an influx of visitors. Could Albania be treading that line? When I visited Dhërmi in May 2024, buildings were being veritably thrown up along the beachfront to prepare for the high season. Cranes line the horizon. In those thronging resort towns, there is no question that the world has gotten wind of this ‘undiscovered gem’.

‘Tourism, if unregulated or purely profit-driven, can lead to the erosion of identity,’ says Professor Sinani. ‘Are we creating spaces for meaningful cultural exchange or merely commodifying our heritage and landscape? Tourism must be approached with a strategy rooted in sustainability, local empowerment and reverence for the land.’

In 2017, Rama set up a joint Ministry of Tourism and Environment to do, ostensibly, just that. Albania has since joined the Global Sustainable Tourism Council, an organisation supported by UNEP and the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). According to UNEP, Albania has increased the percentage of its territory designated as protected areas to 21.4 per cent. The National Tourism Strategy, set out by the minister of tourism and environment, Mirela Kumbaro Furxhi, in October 2024, outlines the country’s sustainable tourism goals, including its eventual accession to the EU and the resultant commitment to its SDGs (sustainable development goals).

‘Having worked in Albania for 18 years, we’ve witnessed incredible change – sustainability has become a key concern, professionalisation has increased, and there is now a critical public debate around construction projects,’ says MVRDV’s Maas. He cites the example of the ‘forest ring’ around Tirana: ‘While many other cities, like Istanbul, are encroaching upon their forests, Albania is creating a protective green belt. Similarly, its efforts to preserve the coastline stand out.’

Galdini, however, is sceptical: ‘Is Albania ready to receive 20 million tourists annually without compromising its ecological, urban and cultural equilibrium? As things stand, the answer is no. We are already experiencing capacity stress in peak seasons: transport bottlenecks, overburdened waste systems, degraded coastlines... The focus on numbers has eclipsed the imperative of quality, sustainability and local benefit.’

At the start of 2025, the government approved a £1.2 billion project by Donald Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, to transform Sazan, an island off Albania’s southern coast, into a luxury resort. Currently untouched, renders show that Sazan will be turned into a shiny futurescape of 10,000 hotel and villa rooms.

The problem is that this was meant to be one of Albania’s protected landscapes; Kushner’s project has been approved off the back of a law passed in February 2024 that makes it easier to override regulations for the purposes of construction. Is Sazan a microcosm, or possibly an omen? Kumbaro Furxhi has said that ‘the interests of nature conservation, biodiversity protection and sustainable development will always prevail over tourism investments’, but does Rama’s declaration at ITP Berlin that ‘[Albania] needs luxury, just like [the] desert needs water’ trump that?

For now, Albania remains one of the last frontiers of Europe. In the village where my husband’s grandparents live, mules are still an established mode of transportation and people subsist off homemade olive oil and hand-slaughtered chickens. There’s not a single Starbucks or McDonald's in Albania. At times, one really does feel that this is the same nation traversed by Lord Byron, who was charmed by it during his 1809 grand tour.

Wherever you go, the black eagle spread against the red flag is a persistent symbol of a people who have fought off many would-be occupiers, from the Ottomans to the Serbs during the Kosovan War that ended just 26 years ago. Yet despite an embattled history, the hospitality of the Albanian people stands out, guided by the common phrase ‘before the house belongs to the owner, it first belongs to God and the guest’.

‘What truly fuels Albania’s allure is not simply the rugged coasts, the alpine landscapes and the archaeological echoes of Illyria and Byzantium, but its profound authenticity,’ says Galdini. ‘In an era of over-curated travel experiences, Albania offers serendipity.’

‘Albania has changed,’ he concedes. ‘If we continue on the path of improvisation, we will face stagnation disguised as progress.’

‘What does it mean to be modern without being uprooted? How can we be European without being diluted? Do we want Albania to remain a place where life is lived deeply, or do we allow ourselves to become an exhibition, where tradition is rehearsed rather than lived?’ adds Professor Sinani. ‘The challenge is to ensure that, in opening ourselves to the world, we do not lose the inward gaze – the silent, dignified continuity of what it means to be Albanian.’

In a new architectural landscape of smooth lines and sinuous curves, I also hope that Albania remains rough around the edges.

Anna Solomon is Wallpaper*’s Digital Staff Writer, working across all of Wallpaper.com’s core pillars, with special interests in interiors and fashion. Before joining the team in 2025, she was Senior Editor at Luxury London Magazine and Luxurylondon.co.uk, where she wrote about all things lifestyle and interviewed tastemakers such as Jimmy Choo, Michael Kors, Priya Ahluwalia, Zandra Rhodes and Ellen von Unwerth.

-

The Lighthouse draws on Bauhaus principles to create a new-era workspace campus

The Lighthouse draws on Bauhaus principles to create a new-era workspace campusThe Lighthouse, a Los Angeles office space by Warkentin Associates, brings together Bauhaus, brutalism and contemporary workspace design trends

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’Wallpaper* takes a tour of Extreme Cashmere’s new Amsterdam store, a space which reflects the label’s famed hospitality and unconventional approach to knitwear

By Jack Moss

-

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the best

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the bestBrands including Bremont, Christopher Ward and Grand Seiko are exploring the possibilities of titanium watches

By Chris Hall