Curated by Lord Foster, a new London show explores Cartier’s pioneering design spirit

Lord Foster is in a buoyant mood. Having designed and curated a new show at the Design Museum in London, ‘Cartier in Motion’, he is still reveling in the delights of aviation and horological history on display. The exhibition charts the evolution of the French company’s fine watchmaking alongside other key innovations of the early-20th century, all pivoting around the character of Louis Cartier, a major point of connection in the evolution of the modern world.

It’s unsurprising that Foster has an interest in the mythos and romance of early aviation, an age when aviators were inventors, craftsmen, test pilots and engineers all rolled into one. Fabled for his love of all things mechanical, Foster’s own image as an architect is burnished by his helicopter-flying, classic-car-restoring persona, not to mention the cutting-edge edifices his studio delivers with machinelike precision. He admits that ‘my association with Cartier began with this project. Deyan Sudjic [director of the Design Museum] asked if I was interested. I’ve always been fascinated by the links between art, architecture, aviation and design.’

The story of Louis Cartier is inseparably intertwined with the dawn of modernism. ‘I was drawn into Cartier’s circle, people like the Brazilian aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont,’ says Foster. The legend goes that, although he didn’t invent the idea of a wristwatch, Cartier was asked by Santos-Dumont to solve the problem of his pocket watch. ‘The wrist strap was designed to stop him fumbling in his waistcoat pocket while he was trying to control an aircraft.’

Cartier’s pioneering design became the Santos de Cartier, a watch that remains in production today. The pilot himself is one of the exhibition’s focal points, with one of his surviving Desmoiselle monoplanes at the heart of the display. Foster is in his element talking about this incredible machine, first flown in 1907. ‘I didn’t expect to find such a truly beautiful object,’ he says of his first encounter with the newly restored aircraft, tucked away in the vintage section at Paris’ Le Bourget Museum. ‘Look at the detail,’ he enthuses. ‘Look at that vertical strut!’ It’s no great stretch to draw parallels between the Desmoiselles’ successful hybrid of art and engineering and some of the great early works of high-tech architecture.

Installation view of the ‘Cartier in Motion’ exhibition at the Design Museum.

These parallels shape Foster’s curatorial approach to the exhibition. ‘There are connections between the city, the purity of line, the architecture, the engineering, all leading up through the romance and the glamour, culminating in the craftsmanship,’ he says. The progression is laid bare in a massive timeline, a mighty research work that joins the aesthetic dots between art, architecture, fashion, engineering, auto and aviation design, and practically every other facet of early-20th century culture.

In among it all is the figure of Louis Cartier, a man for whom the machine held an irresistible lure. ‘Cartier in Motion’ captures these obsessions and the products he created, all set against the backdrop of an age of technological wonder. In addition to the Santos watch, there was the Tank model, another classic, which drew inspiration from the brutish mechanicals and simple form of those early war machines.

Foster and his team are responsible, too, for the staging of the show. The cabinets, which draw on the exquisitely detailed jewellery cases used for display in Cartier’s many stores, are modular and can be adapted should the show travel. Manufactured by Italian museum specialist Goppion, they include curved glass edges and a system that allows freestanding or interlocking displays to create the sense of a grand store, a treasure trove of objects. Spectacular centrepieces act as anchors – the Desmoiselle plane, a model of the Eiffel Tower, and reproductions of the precarious high-rise seating designed by Santos-Dumont to give his dinner guests ‘an aviator’s view’.

Foster suggests that the specially commissioned models in the show have a life beyond the exhibition, becoming limited-edition objects that can travel in their vitrines to Cartier’s global stores. There’s a notable precedent. Back in the 1930s, the Cartier atelier made spectacularly elegant models, such as The Question Mark, a sterling silver scale replica of Point d’Interrogation, the first aircraft to fly from Paris to New York in 1930. This meticulous model was gifted to the Rockefeller Center by France.

The show reiterates Paris’ status as the cradle of modernity, not just in the traditional sense of avantgarde art, architecture and design, but also in terms of manufacturing, engineering and innovation. The 1889 exhibition hailed by Eiffel’s Tower gave visitors a new viewpoint on urbanism. For the first time, they could look down on a city that was not medieval and organic, but organised along rational lines by Haussmann’s grand boulevards. The visual synchronicity with Cartier’s geometric watch forms is hard to resist.

The show also includes three films, covering ‘the purity of line’, Cartier’s connections and what Foster calls the ‘nobility of making’. There will be more than 160 timepieces, as well as posters, marketing material and technical drawings from the Cartier archives. It is a rich evocation of an era hovering on the cusp of something new. ‘The pure geometry of what Cartier was doing in watchmaking anticipated the pure forms of the Bauhaus – however subliminally,’ says Foster, who hopes to ‘open visitors’ eyes to the birth of many of the things we now take for granted’. Can the show attract an audience beyond those who only know Cartier for watches and jewellery? Time will tell.

As originally featured in the Precious Index, our new watches and jewellery supplement (see W*218)

Left, detail of the restored Demoiselle, on show at the Design Museum. Right, Alberto Santos-Dumont in his Demoiselle (1909), the world’s first industrialised aeroplane design. © Cartier

The restored Demoiselle was dismantled at the Le Bourget museum in Paris and transported to the Design Museum, where Lord Foster has made it the star of the ‘Cartier in Motion’ show.

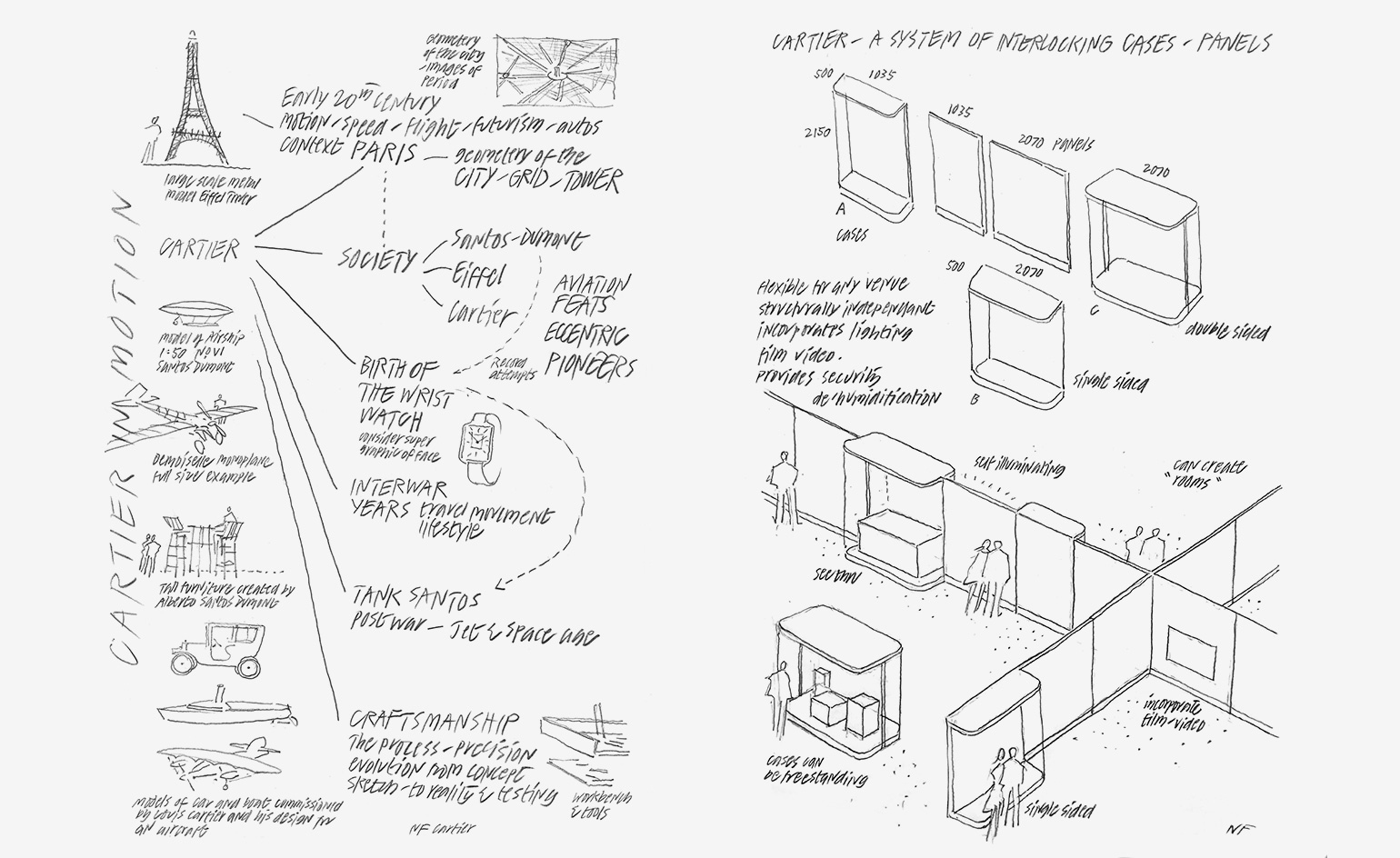

Lord Norman Foster’s original sketches for the exhibition. Foster and his team were also responsible for the staging of the show. The cabinets are manufactured by Italian museum specialist Goppion. Courtesy of Norman Foster

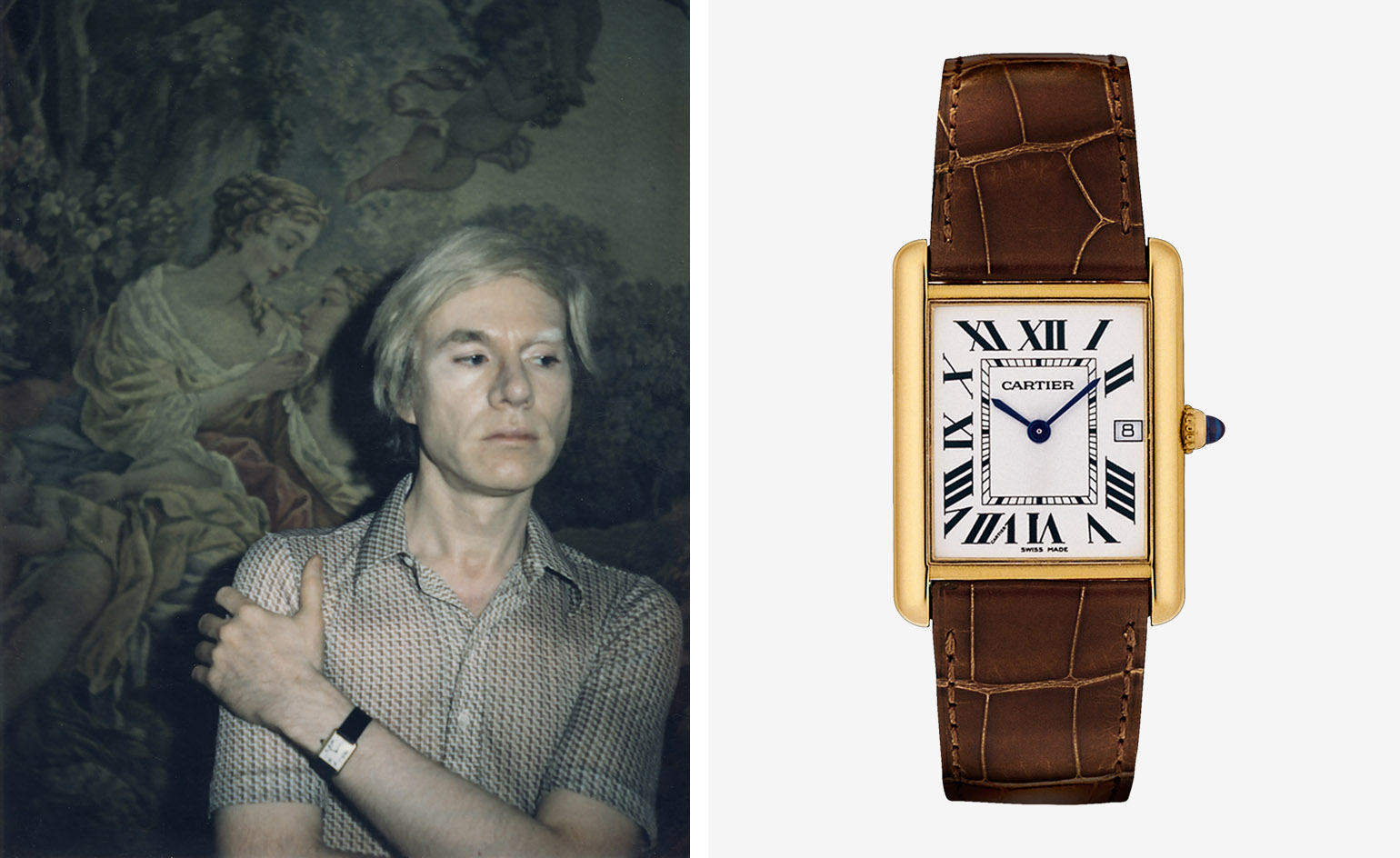

Left, a 1970s Polaroid self-portrait by Andy Warhol wearing his Cartier Tank. Right, ’Tank’ watch (platinum, gold, sapphire cabochon, leather). © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc; Vincent Wulveryck, Collection Cartier. Courtesy of Cartier

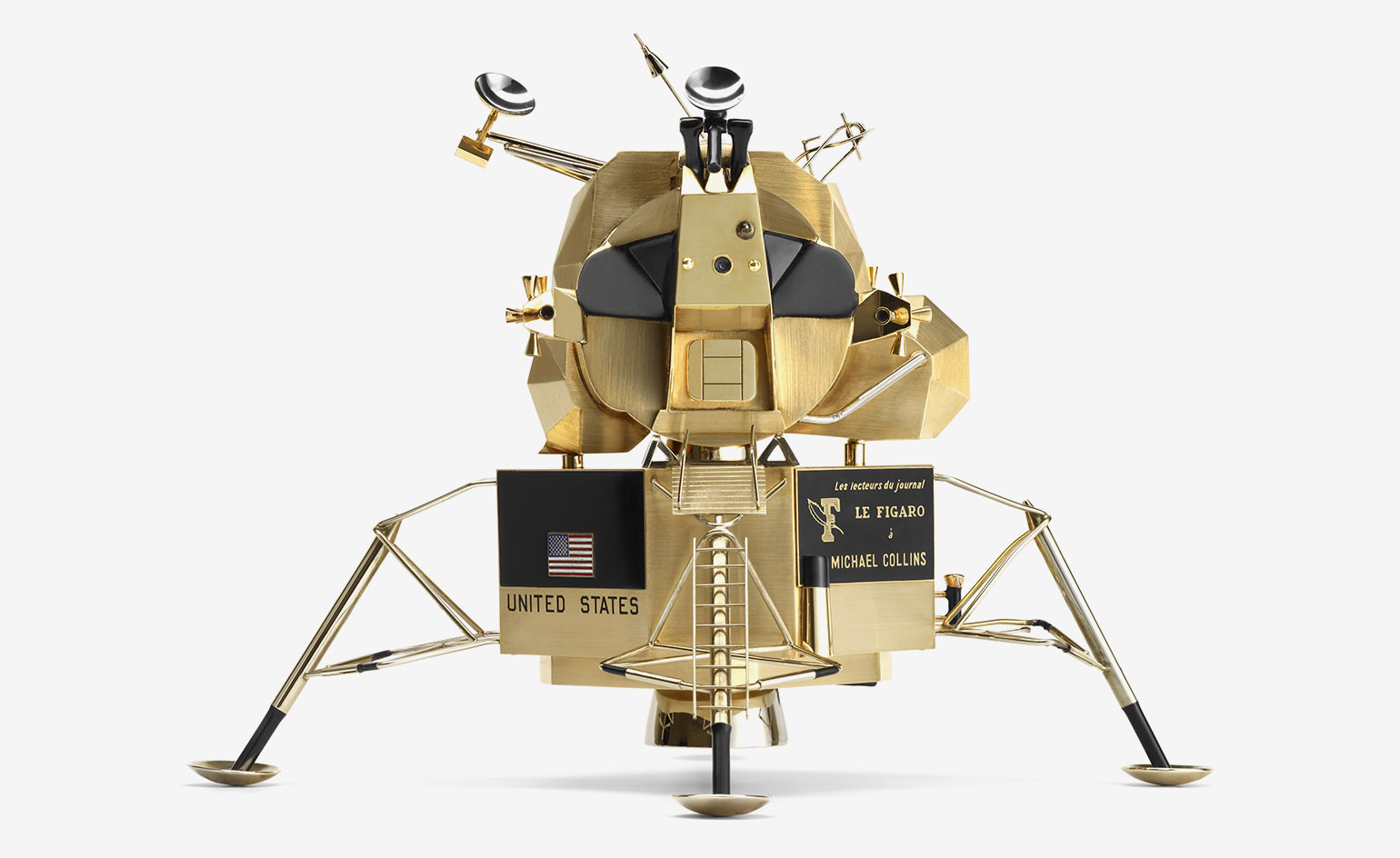

The Lunar Excursion Module (exact replica) made by Cartier in 1969 and presented as a gift to the US in celebration of the Apollo 11 space mission (gold, black lacquer, enamel, engraved). Courtesy of Nils Herrmann, Collection Cartier. © Cartier

‘Gremlin’ charm bracelet (gold, enamel), 1942–43. Courtesy of Nick Welsh, Collection Cartier. © Cartier

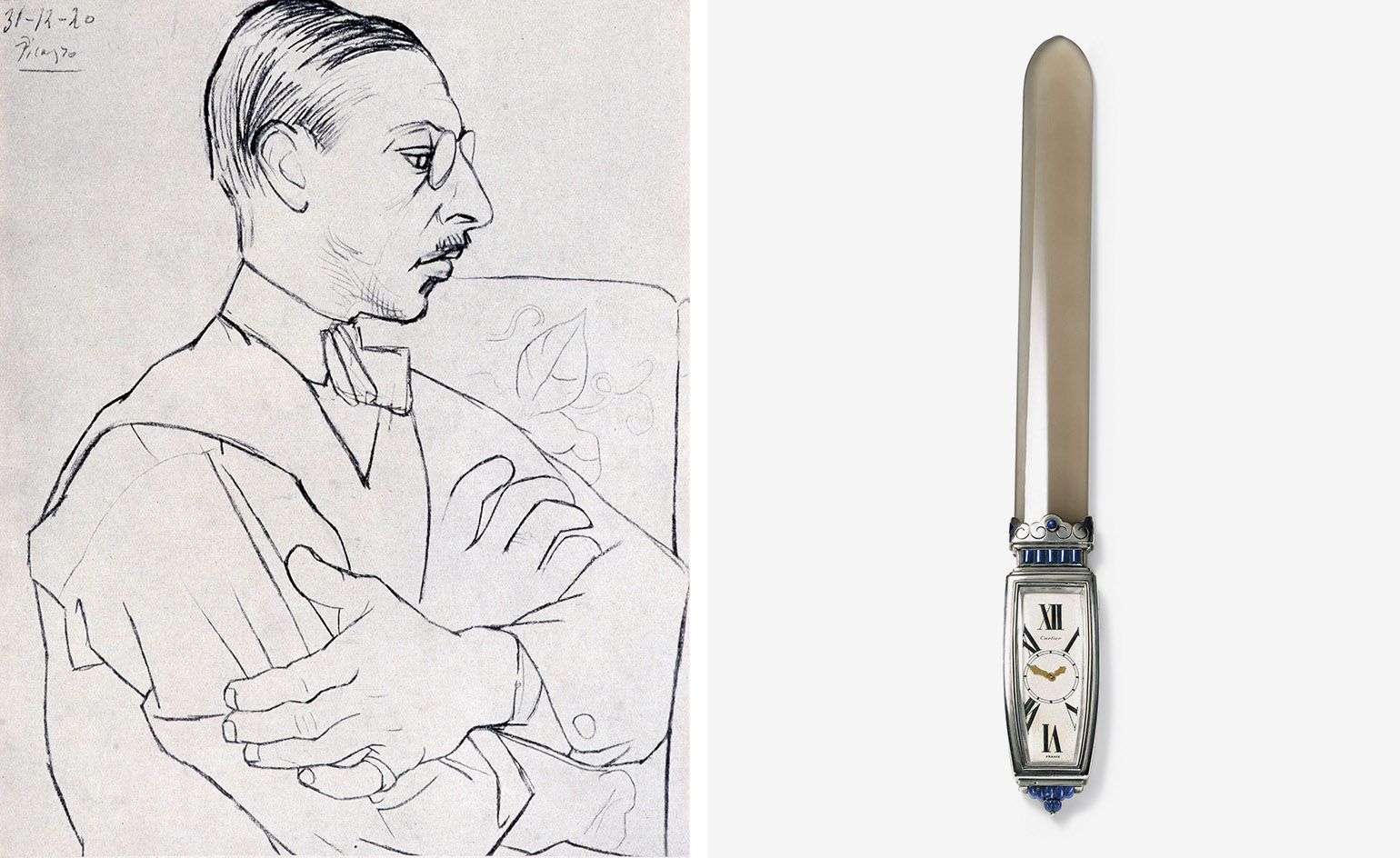

Left, composer Igor Stravinsky by Pablo Picasso. Stravinsky was a passionate aficionado of the Cartier Tonneau (barrel) watch. Right, other objects on display include a 1930s paper knife with watch (silver, gold, agate, lapis lazuli). Courtesy of Collection Particulière. © Succession Picasso; Nick Welsh

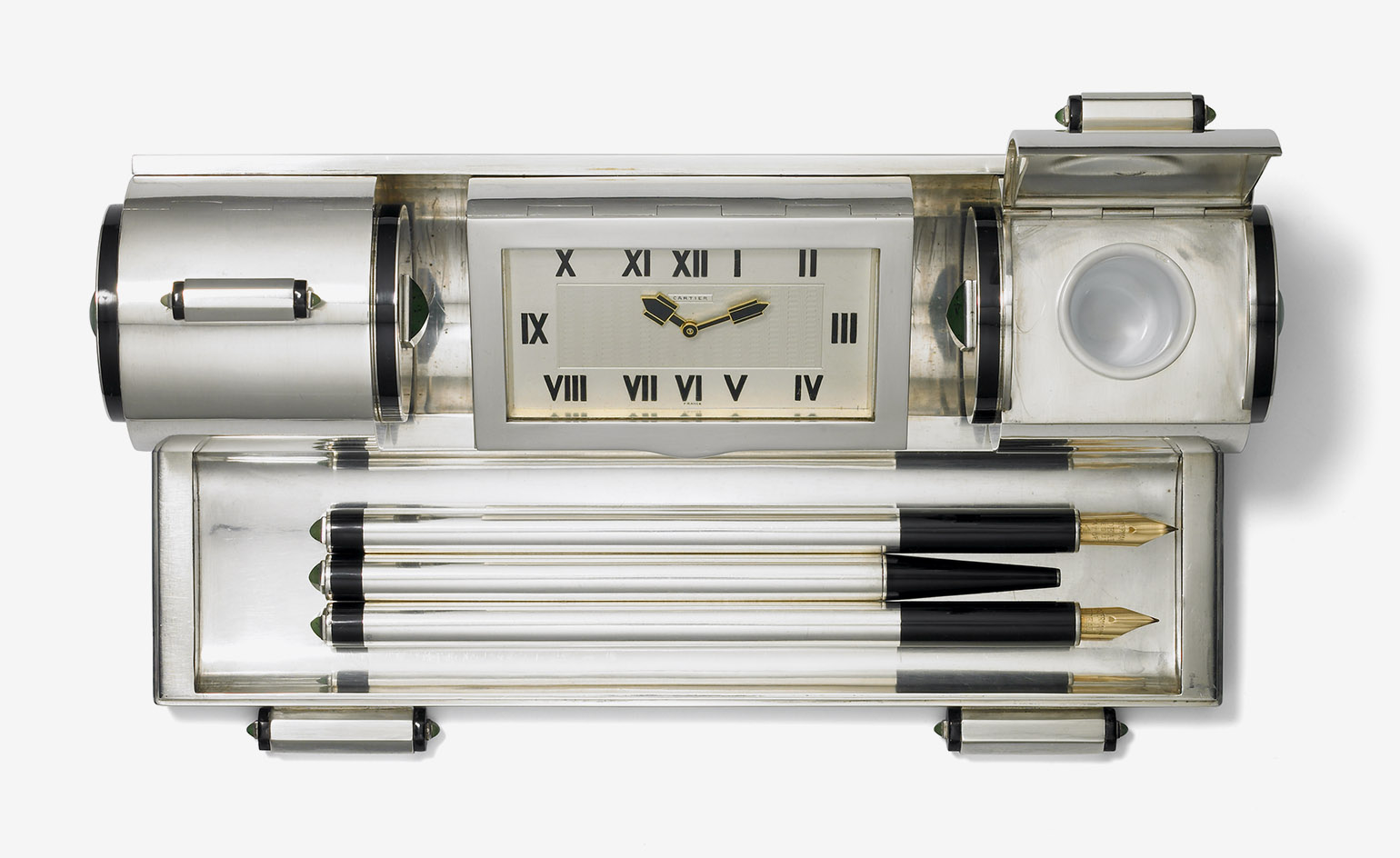

Among the items chosen by Lord Foster to display is this desk set with clock by Cartier Paris for Cartier New York, 1931 (silver, gold, nephrite, black lacquer, enamel). Courtesy Nick Welsh, Collection Cartier. © Cartier

Left, the ‘Tank à guichets’ jumping-hour wristwatch, designed in 1928 (gold, leather). Right, ‘Santos de Cartier’ self-winding wristwatch, designed in 1978 (gold, steel, spinel). Courtesy of Vincent Wulveryck, Collection Cartier. © Cartier

INFORMATION

‘Cartier in Motion’ is on view until 28 July. For more information, visit the Design Museum website

ADDRESS

Design Museum

224-238 Kensington High Street

London W8 6AG

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

Cartier’s major new exhibition opens at the V&A and it’s a gem

Cartier’s major new exhibition opens at the V&A and it’s a gem‘Cartier’ at the V&A in London takes an epic tour through the house’s history and archives

By Hannah Silver

-

Are ‘jump hour’ watches the most enjoyable trend to come out of Watches and Wonders?

Are ‘jump hour’ watches the most enjoyable trend to come out of Watches and Wonders?Watches and Wonders 2025 saw new jump hour watches from Bremont, Cartier, Gerald Charles, Hautlence, Svend Andersen and others

By James Gurney

-

Cartier dials up the glamour at Watches and Wonders 2025

Cartier dials up the glamour at Watches and Wonders 2025Cartier revamps much-loved watch collections, from Privé and Panthère to Tank and Tressage, upping the sparkle at the watch fair in Geneva

By Thor Svaboe

-

Van Cleef & Arpels light up London with the Dance Reflections festival

Van Cleef & Arpels light up London with the Dance Reflections festivalVan Cleef & Arpels are celebrating their ties with the world of choreography with the second edition of the Dance Reflections festival across London

By Hannah Silver

-

Meet the young watchmakers stirring up the industry

Meet the young watchmakers stirring up the industryLoupes at the ready, these artisans are ones to 'watch'

By Thor Svaboe

-

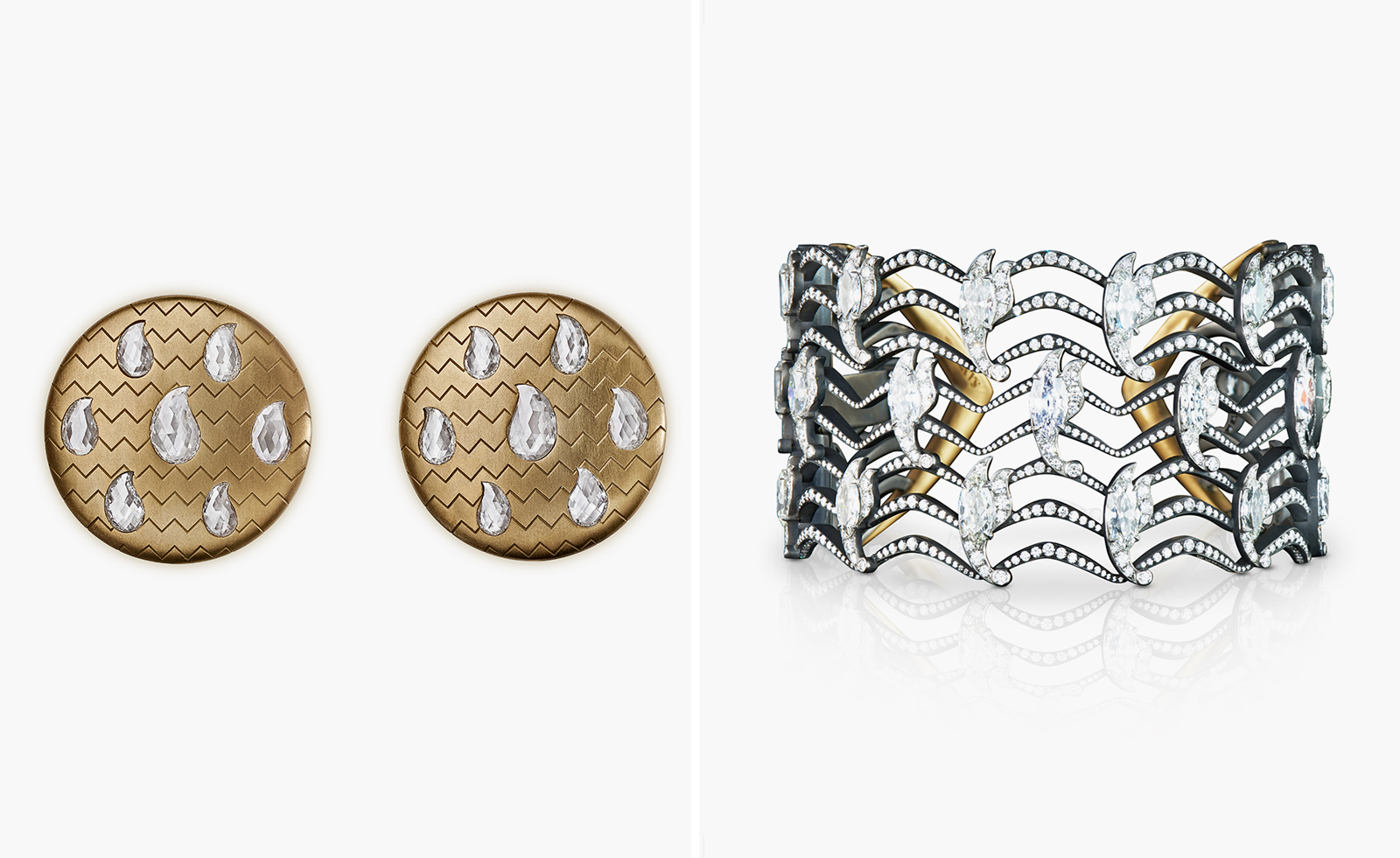

Dazzling high jewellery for statement dressers

Dazzling high jewellery for statement dressersIntricate techniques, bold precious stones and designs unite in these exquisite high jewellery pieces

By Hannah Silver

-

Take a look at the big winners of the watch world Oscars

Take a look at the big winners of the watch world OscarsThe Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève is the Oscars for the watch world – get all the news on the 2024 event here

By Smilian Cibic

-

As London’s V&A spotlights Mughal-era design, Santi Jewels tells of its enduring relevance

As London’s V&A spotlights Mughal-era design, Santi Jewels tells of its enduring relevance‘The Great Mughals: Art, Architecture and Opulence’ is about to open at London’s V&A. Here, Mughal jewellery expert and Santi Jewels founder Krishna Choudhary tells us of the influence the dynasty holds today

By Hannah Silver